Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is most widely used for movement disorders (Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, tremor). In PD, those symptoms respond to DBS that are also improved by levodopa. Therefore, the statement that DBS is indicated “when medications no longer work” is incorrect. The site of stimulation (subthalamic, pallidal) influences the treatment outcome and the possible reduction of medication after the procedure. Since the clarifications prior to DBS are very complex, it makes sense for patients to be presented at a low threshold. Use www.earlystimulus.com to clarify whether referral to a DBS center is appropriate with the question of indication for DBS.

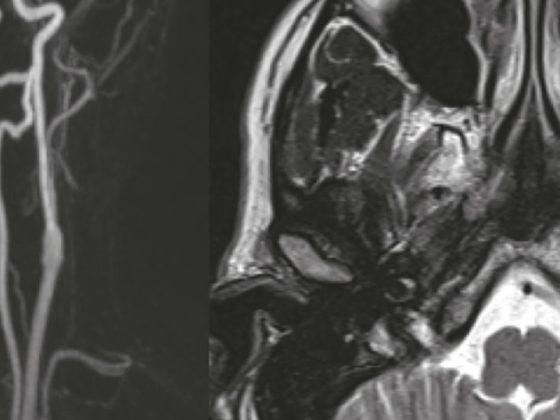

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an invasive treatment in which electrodes are implanted in specific core areas of the brain during a stereotactic neurosurgical procedure. Electrical impulses are delivered via these electrodes, which act on a narrowly defined area, resulting in clinical improvement of certain symptoms.

DBS has been used since the late 1980s, and well over 100,000 patients have now been treated with this therapy. Decisive pioneering work in the development of DBS was done by the neurosurgeon Alim-Louis Benabid and the neurologist Pierre Pollak in Grenoble. Meanwhile, DBS – while still an area of cutting-edge university medicine – has become a routine therapy. Swiss pioneers in the field of DBS were Jean Siegfried in Zurich and Joachim Krauss, who together with Jean-Marc Burgunder treated the first patients with cervical dystonia with DBS in the late 1990s.

Indications for DBS

The broadest application of DBS to date has been in the area of movement disorders. In principle, however, many other pathologies resulting from dysfunction of circumscribed brain areas are amenable to treatment with DBS, such as central pain, epilepsies, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, or psychiatric disorders such as severe obsessive-compulsive disorder or, in some cases, treatment-refractory depression.

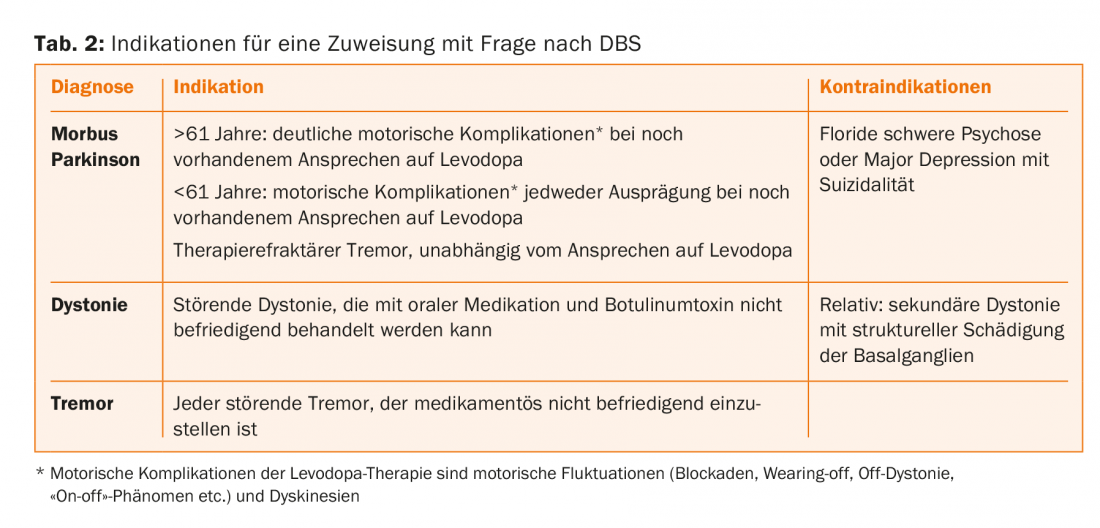

Movement disorders that can be treated with DBS include Parkinson’s disease, dystonia and dyskinesias, and tremor. These indications will be briefly discussed here. Unfortunately, many patients who could benefit from DBS are still not referred to this therapy today, either because DBS is too little known or because of misconceptions among the physicians in the practice, who play the decisive role in referring patients to the center. Correct indication and timely referral to a competent center are of great importance.

Characteristics of Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder with highest prevalence in the more advanced age. Actually, the average age of onset is just over 70, but in practice and especially in the centers, we see an above-average number of young patients with Parkinson’s because the onset at a younger or middle age is so drastic. Histopathologically, there is slowly spreading neurodegeneration with intracellular deposits containing alpha-synuclein (Lewy bodies). These lead to a loss of dopamine-producing neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta. It would be a gross oversimplification to attribute PD to pathology of the dopaminergic system only, as other neurotransmitter systems are also affected (serotonin, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, etc.). However, because the dopaminergic deficit is closely associated with the cardinal motor symptoms of the disease (bradykinesia, rigor, gait disturbance, and optional resting tremor) and because drug substitution treatment of this deficit is possible, the dopaminergic system has a special role in the therapy of PD.

The loss of dopaminergic neurons is compensated by the intact structures for years before motor symptoms occur, which then lead to the diagnosis. The initial treatment often leads to a considerable improvement of the symp-toms (“honeymoon phase”). However, due to progressive neurodegeneration and due to the pulsatile (non-physiological) kinetics of dopaminergic drugs, especially levodopa, so-called motor complications, i.e. fluctuations of the effect and dyskinesias, occur after a few years.

A patient with fluctuations continues to respond in principle to the medications, but in varying degrees temporally throughout the day, resulting in often unanticipated blockages. On the other hand, the effect of the medication can overshoot at times, resulting in involuntary over-movements, i.e. dyskinesias. The often unpredictable interplay between good mobility (“on”), dyskinesias, and poor mobility (“off,” blockage) is a major problem of advanced PD, along with the non-motor symptoms of the disease.

DBS in Parkinson’s disease

Deep brain stimulation can improve the motor symp-toms of PD, and those symptoms respond to DBS that are also improved by levodopa. Therefore, the statement that DBS is indicated “when medications no longer work” is fundamentally incorrect. Just the response to levodopa is a predictor of the outcome of DBS. The key advantage of DBS is that its effect does not fluctuate, which means that the time in “on” without disturbing dyskinesias per day is considerably prolonged. During the honeymoon phase, when the effects of the medication remain constant throughout the day, DBS is certainly premature and it may not provide any additional benefit. However, once motor complications begin, even if mild, DBS has the potential to improve patients’ quality of life.

For subthalamic stimulation, several randomized controlled trials have shown an advantage over drug therapy alone in advanced PD and marked motor fluctuations. In patients up to 60 years of age, significant benefit has been demonstrated from the onset of even mild motor complications. With subthalamic stimulation, once the stimulation parameters are set, dopaminergic medication can be reduced by 50% on average, and sometimes medication can be paused altogether. However, this may carry the risk of non-motor dopaminergic withdrawal symptoms: while motor symptoms are well controlled by stimulation, too deep dopaminergic tone may lead to apathy and dysphoria. Conversely, too much stimulation can lead to impulsive behavior. This illustrates how delicate the postoperative adjustment of pacing parameters and medications is; it belongs in the hands of experienced specialists.

Subthalamic stimulation is a challenging technique and may result in side effects such as an increase in dysarthria, postural instability, or decreased verbal fluency. These risks could be related to reducing dopaminergic medication.

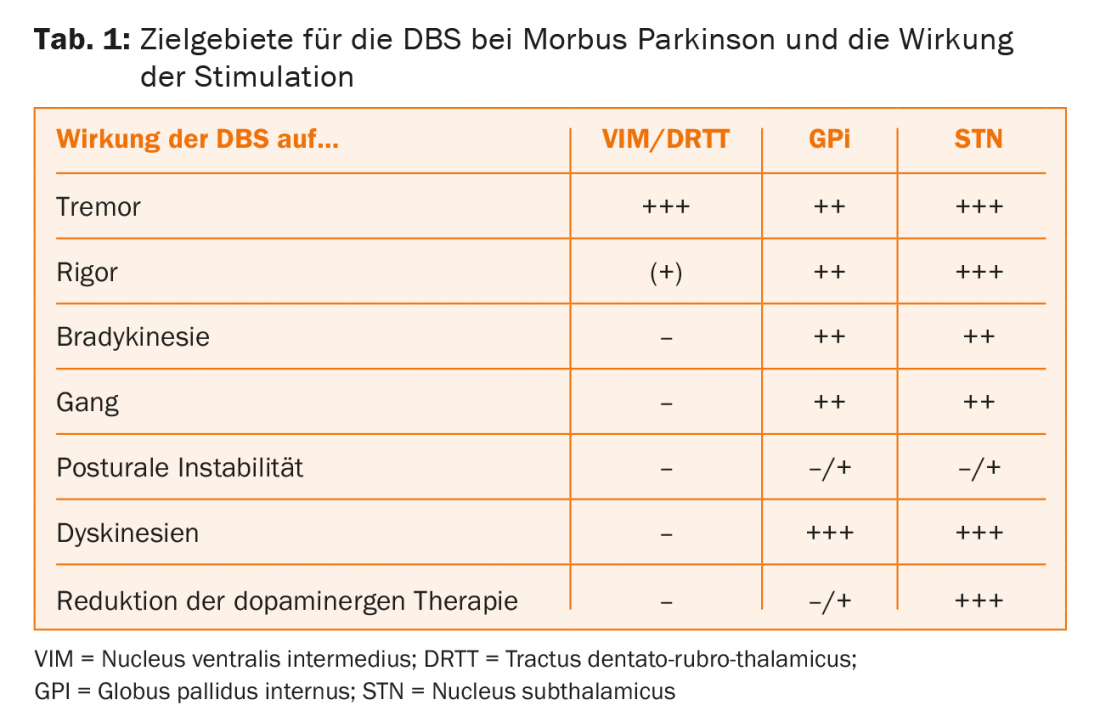

Unlike subthalamic stimulation, pallidal stimulation, which is used far too infrequently, involves little or no reduction in medication. Worsening of axial symptoms is not expected with pallidal stimulation. Again, stimulation acts on the levodopa-sensitive parkinsonian symptoms, but pallidal stimulation also has a potent direct effect against the dyskinesias and therefore does not allow dopaminergic medication to be reduced. Pallidal stimulation, although somewhat less potent than subthalamic stimulation, is well suited for elderly and fragile patients with relative contraindications to subthalamic stimulation (Table 1).

Weighing the pros and cons of DBS is complicated. Therefore, it makes sense for patients to present with the question of DBS at a fairly low threshold. Absolute contraindications to DBS include surgical reasons (e.g., mandatory anticoagulation), nonresponse to levodopa (atypical Parkinson’s syndrome), and active major depression or psychosis. Such psychiatric symptoms should be treated with medication before elective surgery. Relative contraindications to subthalamic stimulation include the presence of axial symptoms unresponsive to levodopa and age older than 70-72 years. However, these relative contraindications do not apply to pallidal and thalamic stimulation, which are also therapeutic options in elderly patients when indicated.

The indication (Tab. 2) must be carefully weighed against the risks. The risks of the procedure are bleeding (<1%), infection, and suboptimal placement of the electrode with required surgical revision. The online program EARLYSTIMULUS can be very helpful in assessing whether referral to a DBS center is appropriate with the question of indication for DBS: www.earlystimulus.com. Stimulation itself is reversible; if a setting causes side effects, it can be reprogrammed without leaving permanent damage. However, stimulation is a purely symptomatic therapy; PD continues to progress.

Because dopaminergic symptoms can be treated with drugs and complications of drugs can be treated with stimulation, in the 21st century we are faced with a new manifestation of far-advanced PD: a disease with dementia, falls, dysphagia, and dysarthria after 20-25 years of disease. In such a situation, stimulation is still effective, but in the meantime, other stimulation-resistant symptoms take center stage.

DBS for dystonia

Therapy of dystonia with oral medications is not very successful, partly because of the side effects. The more focal a dystonia is (blepharospasm, cervical dystonia), the easier it is to treat with botulinum toxin injections. However, this therapy has limitations, especially in segmental and generalized dystonia; here DBS is indicated and can help. Certain forms of dystonia (and dyskinesias) respond particularly well to pallidal stimulation (DYT1, 6, 11, tardive dystonia/dyskinesias). In many cases, however, it is not possible to predict how good the response to DBS will be before the procedure. This is a significant difficulty for prognostic counseling of DBS candidates. The dystonias with structural damage to the basal ganglia (pathological MRI) are generally much less responsive, if at all, to DBS than the idiopathic genetic forms. The response of dystonia is much slower than in Parkinson’s disease and is often visible and assessable only after weeks. Because dystonia is not a progressive neurodegenerative disease, the benefits of DBS are likely to be maintained throughout life.

DBS for tremor

All tremors respond to stimulation in the nucleus ventralis intermedius (VIM), regardless of the pathophysiology of the tremor. Recently, the target area has shifted somewhat, as stimulation of the tractus dentato-rubro-thalamicus, located just below the VIM, is thought to produce better effects with fewer side effects. VIM-DBS can also be used in the very elderly and never leads to psychoorganic symptoms as a side effect of stimulation. DBS for tremor (essential tremor, Parkinson’s disease, Holmes syndrome, multiple sclerosis, post-stroke, etc.) is a significantly underutilized potent therapy.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(5): 22-26.