At the annual meeting of the Swiss Neurological Society in late October 2014, a session focused on encephalitides. These acute life-threatening diseases are rare, but the different etiologies and therapies pose a tremendous challenge. Anti-NMDAR encephalitis, which is based on an autoimmune reaction against NMDA receptors, is being diagnosed with increasing frequency.

(ee) Prof. Randolf Klingebiel, MD, Neuroradiology in the Park, Zurich, provided information on the various aspects of imaging. Encephalitides present challenges in several ways. Despite different causes, patients often present with similar clinical symptoms, and under immunosuppression, symptoms and course are often atypical. Even with treatment, the lethality is high: it is 15-20% for meningococcal encephalitis and even 20-30% for herpes simplex encephalitis. There are a variety of possible complications (herniation, ischemia, etc.), and treatment as early as possible (<3 hours) is essential.

Clinical symptoms determine imaging

The relevance of imaging depends on the clinical presentation. In the meningitic form with fever, headache, vomiting, and neck stiffness (no loss of consciousness), treatment is started immediately after blood samples and CSF are obtained; imaging is done afterward. In the encephalitic form (impaired consciousness, behavioral changes, focal neurologic deficits such as seizures or cranial nerve deficits), imaging is performed after the initial clinical examination, followed by blood and CSF sampling and empiric therapy.

Upon admission to the hospital, emergency imaging is ordered in two situations:

- For encephalitis symptoms – a CT is usually sufficient.

- If purulent CSF has already been collected: Sources of infection such as sinusitis, which can be addressed surgically, must be excluded.

In the course, imaging may become necessary if complications occur, the response to therapy needs to be monitored, or structural changes need to be documented.

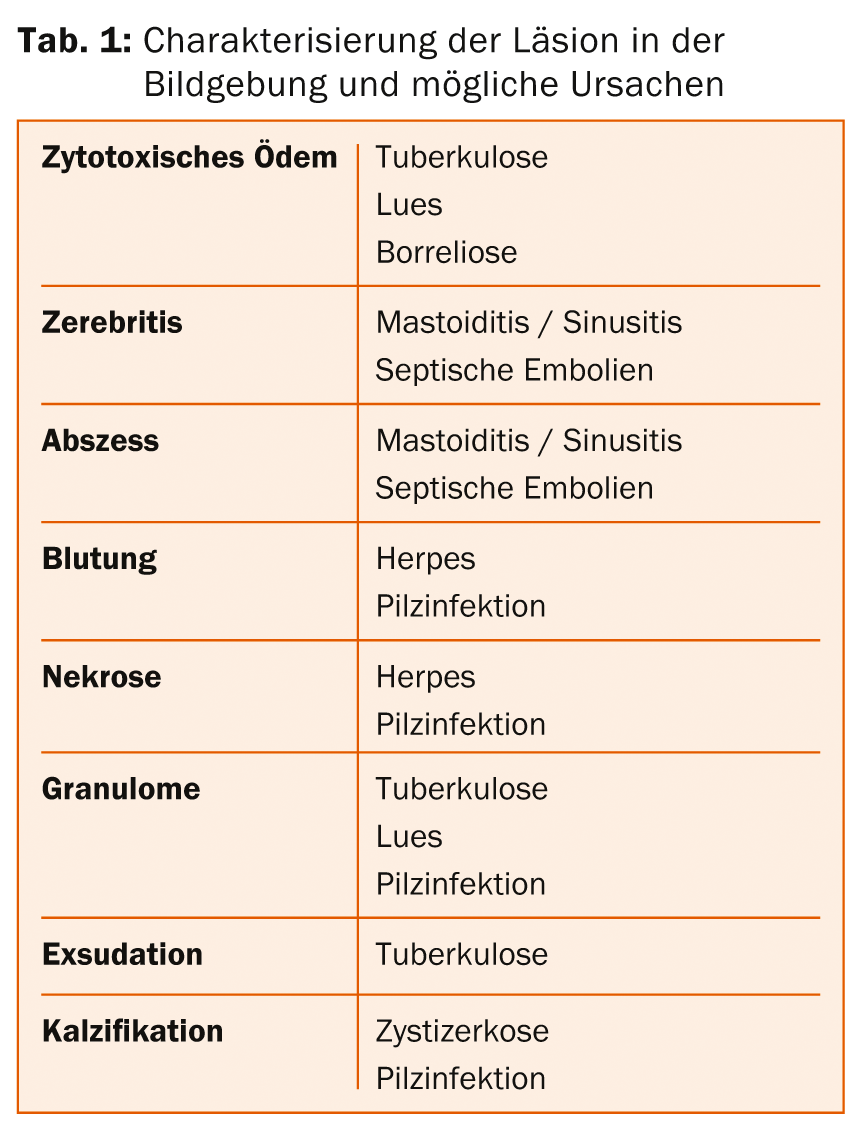

CT and MRI are the primary imaging modalities available, but ultrasound and angiography may also be used for specific issues. Weighting plays a significant role in MRI, as certain structures can only be visualized with the appropriate form of imaging, e.g., microabscesses, differentiation between vasogenic and cytotoxic edema, or the exact extent of an empyema. CT, on the other hand, is good for diagnosing intracranial pressure elevation and for visualizing the skull, skull base, and midface (e.g., sinusitis/mastoiditis), vessels and vascularization, calcifications, and hemorrhages. The character of an intracranial lesion often already gives clues to the cause (Table 1).

Autoimmune encephalitis

The “new” disease anti-NMDAR encephalitis was presented by Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, University of Barcelona (Spain) and University of Pennsylvania (USA). In 50% of patients with encephalitis, the etiology remains unknown. It is likely that a proportion of these patients suffer from anti-NMDAR encephalitis, in which antibodies to the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor are produced in the hippocampus. The disease was first described in 2007. It begins with prodromal symptoms such as agitation, psychotic episodes, catatonia, memory, speech, and movement disorders, or seizures; as it progresses, consciousness disorders, hypoventilation, and dysautonomia are added. Psychotic symptoms are often the first signs, and patients are initially treated in psychiatric institutions until other symptoms are added.

Patients usually spend weeks to months intubated in the ICU, and when they awaken, symptoms resolve as they occur. Very exceptionally, the MRI remains unremarkable throughout the disease. Most patients have complete amnesia for the duration of the disease after recovery, which is, as the speaker put it, “probably a blessing for them.” Recovery can take a long time, but steady improvement occurs in most cases; after 24 months, about 80% of patients have a score of 0 (no symptoms) to 2 (mild impairment) on the modified Rankin scale.

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis predominantly affects women under 40 years of age, with an age peak between 18 and 29 years. Approximately 50% of patients over 14 years of age have a paraneoplastic syndrome due to a previously undiagnosed teratoma. The older the patient, the more likely the association with teratoma. Relapses are more common in patients without tumor and without immunotherapy (corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins, plasmapheresis, rituximab, cyclophosphamide 9).

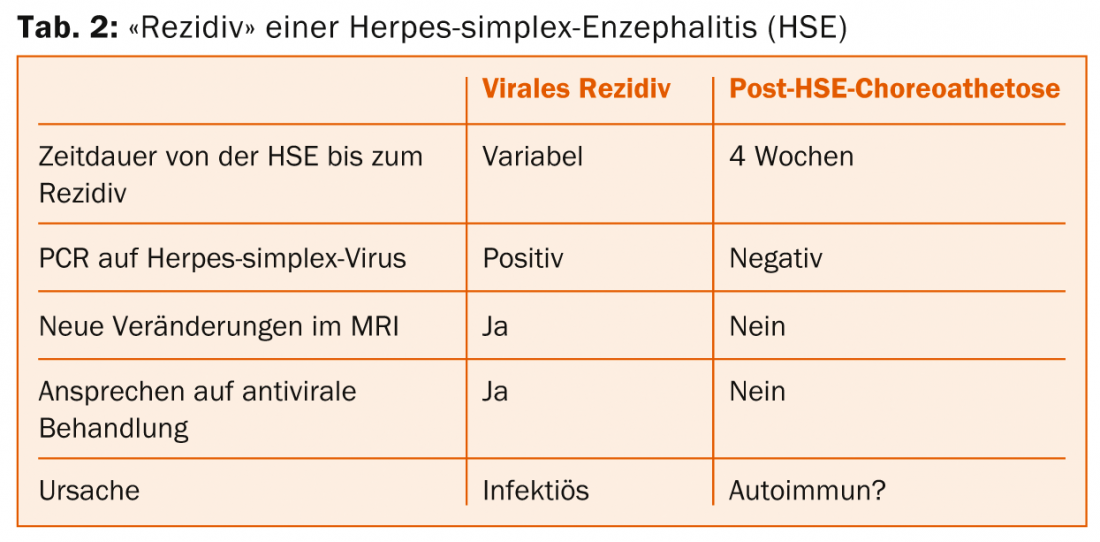

A number of other syndromes have now been described in which antibodies are formed against neuronal surface proteins or synaptic proteins. Clinical symptoms include encephalitis, seizures, psychosis, and agitation, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea). The discovery of these antibodies and their effects has overturned paradigms in the diagnosis and treatment of various neurological and psychiatric disorders. For example, there is evidence that certain “recurrences” of herpes simplex encephalitis with choreoathetosis are not true recurrences but autoimmune encephalitides (Table 2).

Source: 2014 Joint Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society of Critical Care Medicine and the Swiss Neurological Society, October 29-31, 2014,

Interlaken

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2014; 12(6): 42-43.