The number of people suffering from diabetes continues to rise. According to an estimate by the International Diabetes Federation, approximately 592 million people will be affected in 2035. This disease, especially if inadequately treated, is associated with an increased risk of mortality. A practical overview of the best possible individual therapy strategy.

The number of patients suffering from diabetes continues to increase. According to an estimate by the International Diabetes Federation, the number of people affected will increase from 382 million in 2013 to 592 million in 2035 worldwide [1]. The disease is associated with an increased risk of mortality. For example, a 50-year-old person with diabetes loses an average of six years of life compared with a healthy person, much of it due to cardiovascular disease [2]. With increasingly effective and individually adapted therapies, attempts are being made to counteract this risk. In 2008, it was shown that 55-year-old patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria can benefit from intensified diabetes therapy with multiple drug combinations and lifestyle adjustments. Mortality incidence decreased by 46% in the intervention group (p=0.02) [3]. From these data, it appears that a successful therapeutic approach is a multimodal one. Depending on the constellation of findings, the overall concept includes smoking cessation, lipid lowering with statins, blood pressure control with ACE inhibitors/ sartans, secondary prevention with aspirin in the presence of cardiovascular diseases and, of course, diabetes therapy.

Step by Step

Many physicians still shy away from intensifying diabetes therapy in particular, but a successful therapy concept can be developed on the basis of three steps, according to Prof. Dr. Roger Lehmann, Head of Diabetology, Clinic for Endocrinology, Diabetology and Clinical Nutrition, University Hospital Zurich.

Step 1: Setting the individual HA1c target

Step 2: Determine the best individual therapy: personal preferences and medical priorities.

Step 3: Think in terms of substance classes – from this, use the drug with the best evidence.

In addition to the clinical findings, the patient’s wishes are also decisive for successful therapy planning and implementation. The following claims are often made from the patient’s perspective:

- the absence of hypoglycemia

- the avoidance of weight gain

- a preferred oral administration instead of injection

- a preferred once-weekly administration than a daily one

- Lowest possible number of tablets required in total (combination therapy preferred)

Taking these personal preferences into account is partly crucial for maintaining patient motivation and thus for the success of the targeted therapy.

Four important questions

In addition to personal preference, the accompanying clinical circumstances are an equally important factor to consider when determining diabetes medication. To determine the best individual therapy, Prof. Lehmann gave the clinicians a catalog consisting of four questions.

First of all, it should be clarified whether there is an insulin deficiency . This is manifested by symptomatic hyperglycemia, which manifests clinically as polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss, and volume deficiency; in the worst case, metabolic decompensation is imminent. If this is the case, the patient needs insulin. Basically, there are different regimens to choose from, ranging from the basic bolus principle to mixed insulin with long- and short-acting components to the combination of mixed insulin and GLP-1 RA. In the sense of step 3, the mixed insulin is to be favored here and here specifically Tresiba, since this is superior to one of the previous standard insulins Lantus both in the prevention of severe as well as nocturnal hypoglycemia and the reduction of the 3-point MACE (major adverse cardiovascular events), according to the speaker. If necessary, insulin can also be given only temporarily and possibly discontinued in the course of the individual therapy of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The second clinical question revolves around glomerular filtration rate (GFR). At a GFR <30 ml/min, DPP-4 inhibitors and, if necessary, additional basal insulin should be given. However, this combination represents a trade-off, he said, because it can lead to hypoglycemia and weight gain. Among DPP-4 inhibitors, linagliptin was preferable because it did not require dose adjustment at the aforementioned GFR, he said.

With a GFR between >45-60 ml/min, metformin is recommended first, with early combination with SGLT2 inhibitors or with a BMI >28 kg/m², combination with GLP-1 RA is reasonable. Prof. Lehmann emphasized that an early combination with lower doses is more sensible and often has fewer side effects than monotherapy with a steady increase in the dose. If this combination is not sufficient to achieve the jointly defined goal, a DPP-4 inhibitor or basal insulin or gliclazide can also be added here as a representative of the sulfonylureas. It should be borne in mind here that combining several drugs with the same mechanism of action does not confer any advantage. Therefore, a combination of GLP-1 RA and DPP-4 inhibitors should be refrained from. GLP-1 RA and SGLT2 inhibitors are particularly suitable in cases of impaired renal function, as the drugs have been shown in various studies to have a nephroprotective effect in addition to a reduction in mortality [4–6]. SGLT2 inhibitors have the advantage that they can be taken orally and treatment costs are lower than GLP-1 receptor agonists, which must be injected. The speaker cited empagliflozin among the SGLT2 inhibitors and liraglutide and semaglutide in the GLP-1RA group as drugs with the best evidence.

If GFR falls to >30 to <45 ml/min, only half the metformin dose should be given.

In addition to the question of renal function, the presence of cardiovascular disease is also crucial for drug selection. If this is demonstrably present, treatment can proceed in accordance with the therapy recommendation for a GFR >45-60 ml/min. Even in asymptomatic, i.e. mostly undiagnosed patients, this approach hardly changes. Only first-line therapy receives an additional option here with the direct combination of metformin and DPP-4 inhibitors in addition to the combination options already mentioned above. Escalation is with gliclazide (sulfonylurea) or basal insulin.

The fourth clinical question is whether the diabetic patient has heart failure . If this is affirmed , metformin in combination with SGLT2 inhibitors is the first choice.

In the course, DPP-4 inhibtors or subsequently basal insulin may be added.

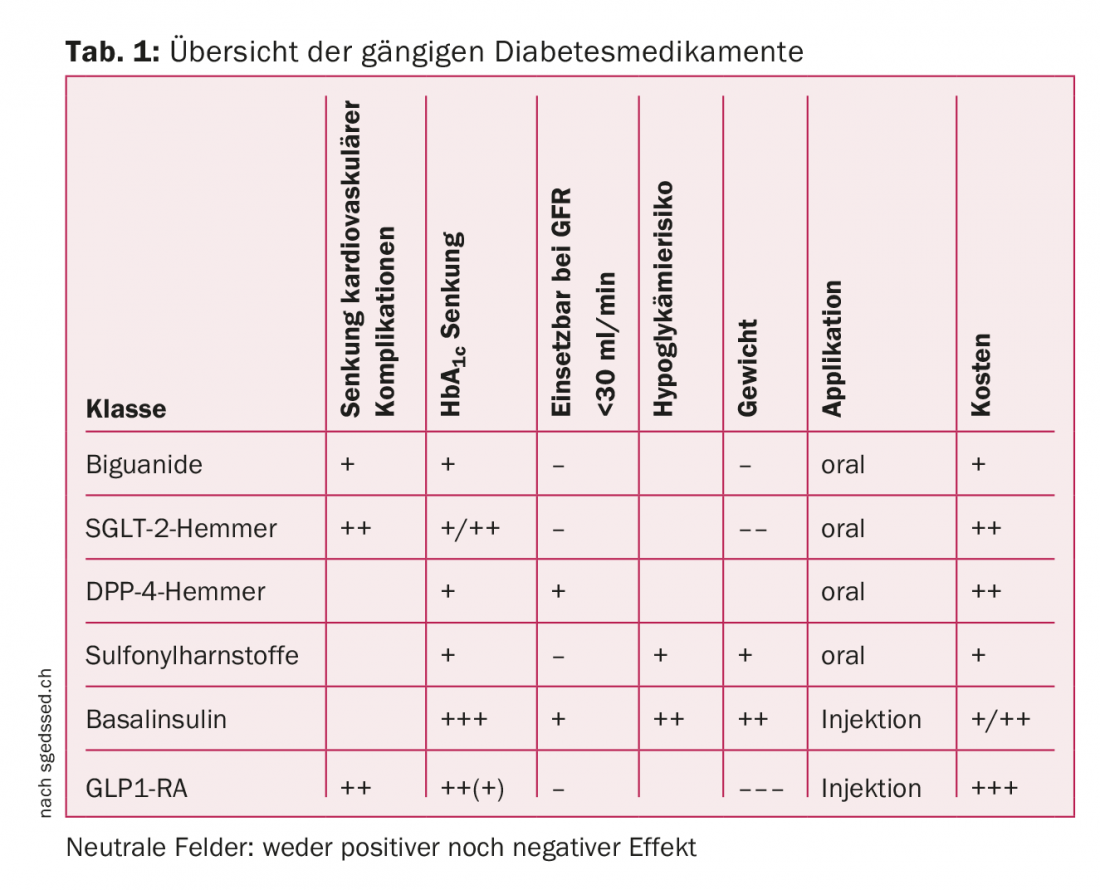

An overview of the various drugs mentioned is given in Table 1.

Take-Home

Based on the available data, Prof. Lehmann emphasized the importance of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP 1 RA in the treatment regimen of type 2 diabetes. In large endpoint studies, empagliflozin (GLP-1 RA) and liraglutide (SGLT-2 inhibitor) were shown to reduce all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, to provide nephroprotection, and, with their favorable effect on weight development and hypoglycemia risk, to provide an additional benefit in the context of multifactorial diabetes treatment. [4–6]. Explicitly discussed prior to initiation of therapy is the fact that there is an increased risk of developing urogenital infections under SGLT-2 inhibitors due to glucosuria.

If the patient’s clinical findings or wishes change during the course of therapy, the established therapy regime should be reconsidered. According to the speaker, timely intensification of therapy is crucial for adequate treatment. If this is delayed by one year with simultaneous poorly controlled blood glucose, this leads to a significant increase in cardiovascular events [7].

Source: Medidays Zurich, September 4-8, 2017

Literature

- www.idf.org/diabetesatlas, 6th edition, 2013

- Rao Kondapally Seshasai S, et al: Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(9): 829-841.

- Gaede P, et al: Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(6): 580-591.

- Marso SP, et al: Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(4): 311-322.

- Zinman B, et al: Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(22): 2117-2128.

- Wanner C, et al: Empagliflozin and Progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(4): 323-334.

- Paul SK, et al: Delay in treatment intensification increases the risks of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2015; 14: 100.

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(5): 36-38

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(10): 36-38