Fatigue is associated with the distressing sensation of unusual, intense fatigue and exhaustion, and can lead to significant reductions in performance and even disability. Many cancer patients are affected by tumor fatigue. Despite this, fatigue remains underdiagnosed. However, the diagnosis is a prerequisite for therapy and rehabilitation. A detailed medical history, specific questionnaires, and keeping a fatigue diary can be helpful in making a diagnosis. During the assessment, it should always be considered that fatigue can also be triggered by non-tumor-associated factors that are at best easily treatable, e.g. depression, sleep or nutritional disorders. Usually there are several causes resp. Influencing factors jointly present.

Almost every tumor patient complains of fatigue, exhaustion, or lack of energy at some point during their tumor disease. Such complaints manifest themselves on a physical, cognitive and affective level and are subsumed under the collective term “tumor-associated fatigue” (CrF). They are usually not related to previous exertion and can hardly be influenced by rest. The symptoms can be self-limiting, but can also become chronic and persist for years after tumor therapy has been completed [1]. Depending on the type and severity, the suffering of patients and relatives is considerable. According to recent studies, tumor fatigue is also associated with shorter survival [2].

Fatigue, exhaustion and lack of energy are universal phenomena that can occur not only in tumor diseases, but also as symptoms of numerous other health disorders and as therapy (side) effects. Moreover, these symptoms also occur in the normal population [3]. This is why thorough diagnostics and differential diagnostic considerations are so significant.

Causes and concomitant factors of tumor fatigue

If a tumor patient suffers from fatigue and exhaustion, this means that the complaints are “tumor-associated” in the sense that they occur at the same time as a tumor disease or its therapy, but it does not necessarily mean that they are caused by it.

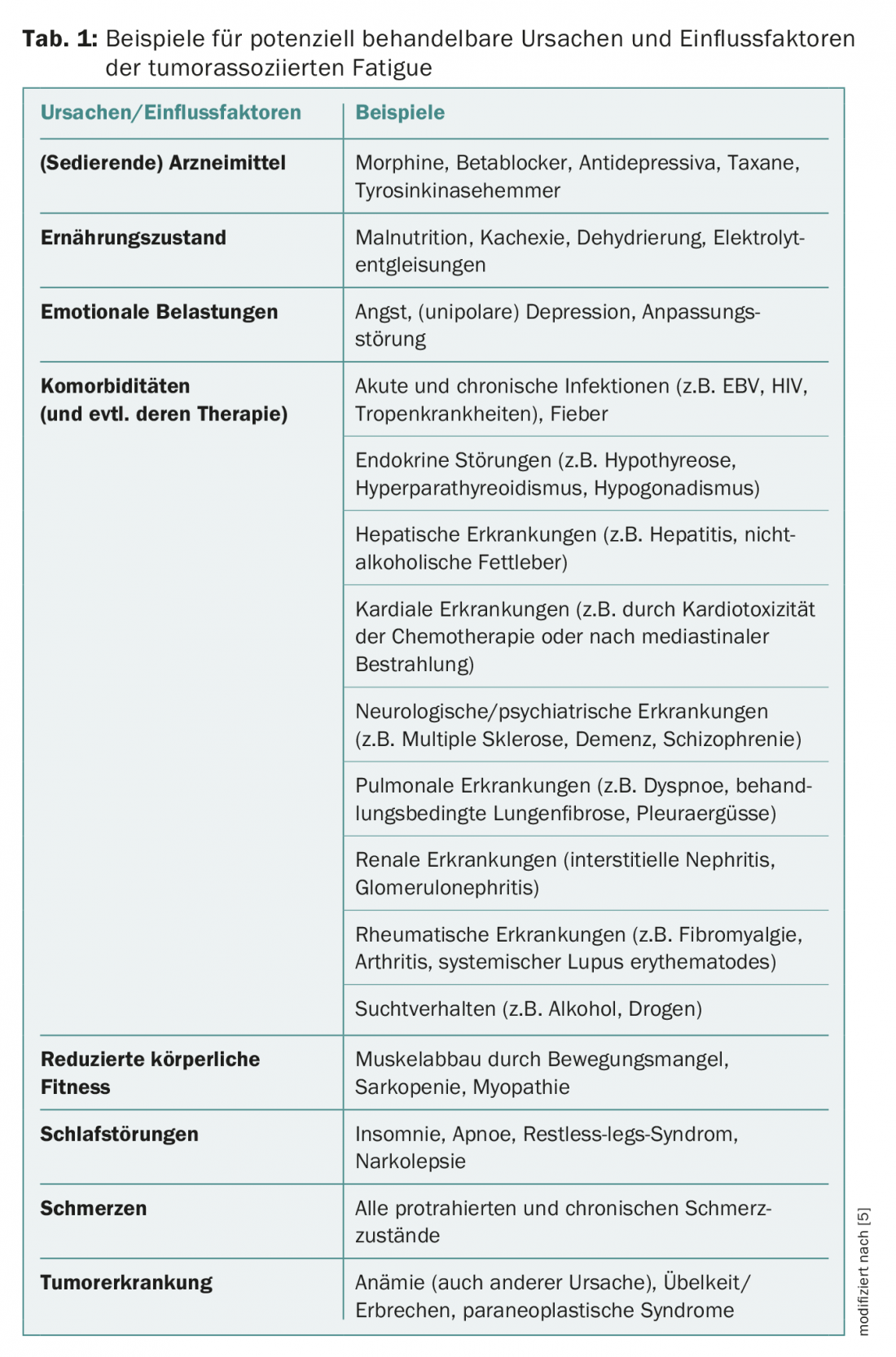

If a patient complains of fatigue and exhaustion, one is likely to wonder whether these symptoms might underlie (previously undetected) progression of the tumor disease or whether ongoing tumor therapy might be responsible. Accordingly, the necessary diagnostic steps will be taken at most. However, in order to identify causes outside the tumor (and possibly to treat them causally), the diagnosis of tumor-associated fatigue should always be a differential diagnosis. It should be noted that tumor fatigue is considered a complex, multicausal event, and most patients may have multiple causes or contributing factors simultaneously [1]. Differentially relevant (co-)causes and influencing factors of tumor-associated fatigue may include, for example, sedating drugs, emotional stress, and comorbidities (Table 1).

In the context of differential diagnosis, it is also useful to distinguish it from other fatigue states described in the ICD-10, such as postviral fatigue syndrome, neurasthenia, or a burnout syndrome [4]. Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) can also be considered in principle.

Diagnostics and differential diagnostics

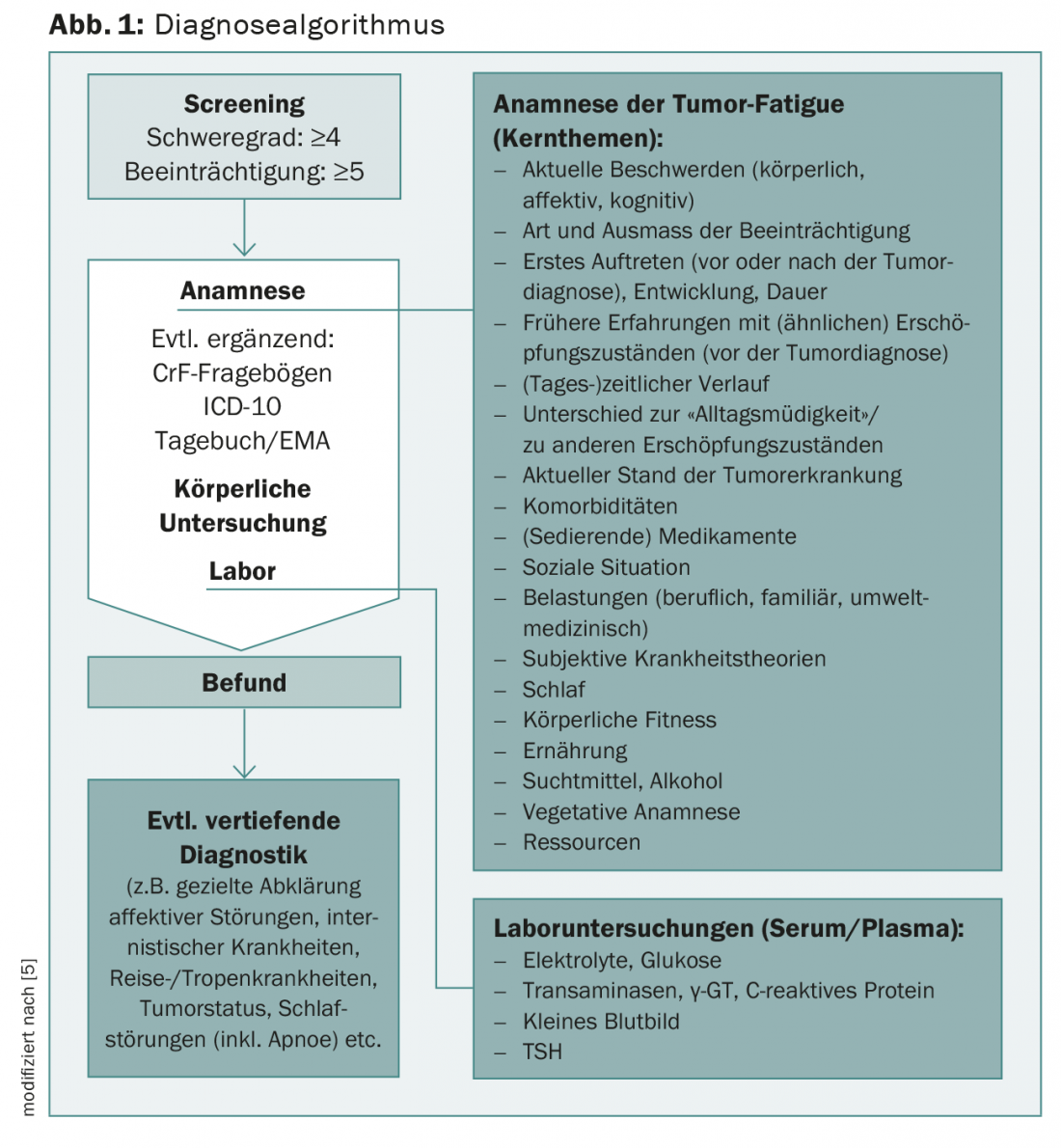

The complexity of the situation requires a differentiated diagnostic approach (Fig. 1). Specifically for treatment planning, it is necessary to distinguish patients with treatable causes and contributing factors from those for whom specific causes/influencing factors cannot be identified. The former should – as far as possible – be treated causally (possibly additionally symptomatically), the latter receive only suggestions for symptomatic therapy [1].

Fatigue Screening

The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) fatigue guideline states, “All patients should be screened for fatigue at their initial visit, at regular intervals during and following cancer treatment, and as clinically indicated” [5]. Screening is used to filter out, at low cost, patients who may have clinically relevant tumor-associated fatigue and who are impaired as a result.

According to a suggestion of the NCCN 2013, a numerical scale from 0-10 can be used for this purpose. A threshold of 4 (for intensity) and of 5 (for impairment) is considered clinically relevant [1]. Following Kenneth L. Kirsh and colleagues, fatigue screening can also be done with a short question (“Are you tired all the time or very often without any reason?”) and/or questionnaires [6].

Medical history

Because tumor-associated fatigue is a subjective event that is primarily assessed by patient self-report, history is considered the most important component in the diagnostic process [1]. Exploration of various anamnesis topics such as current complaints and previous experiences with fatigue states has proven useful in clinical practice (Fig. 1).

The question about the first onset of fatigue symptoms and the situation in which the complaints began is diagnostically quite productive. For example, if a patient reports that fatigue first appeared eight years before the initial diagnosis of his tumor disease and that he was also diagnosed with multiple sclerosis at that time, it is rather unlikely that the complaints are based (only) on tumor-associated fatigue. The question about the course of the complaints (type, intensity, improvement, worsening) can then contribute to further clarification.

The question of experienced differences from “everyday fatigue” can also be diagnostic: Almost all patients with tumor-associated fatigue are able to clearly differentiate their current complaints of fatigue from other fatigue states [7]. As a rule, they also state that they have never experienced a state of exhaustion like the present one before their tumor disease.

When asking about current medication, not only prescription but also other medications (including complementary medicine) should be asked in order to be able to consider pharmacodynamic interactions as a (co-)cause of the fatigue symptomatology, if necessary.

Tumor Fatigue Questionnaires

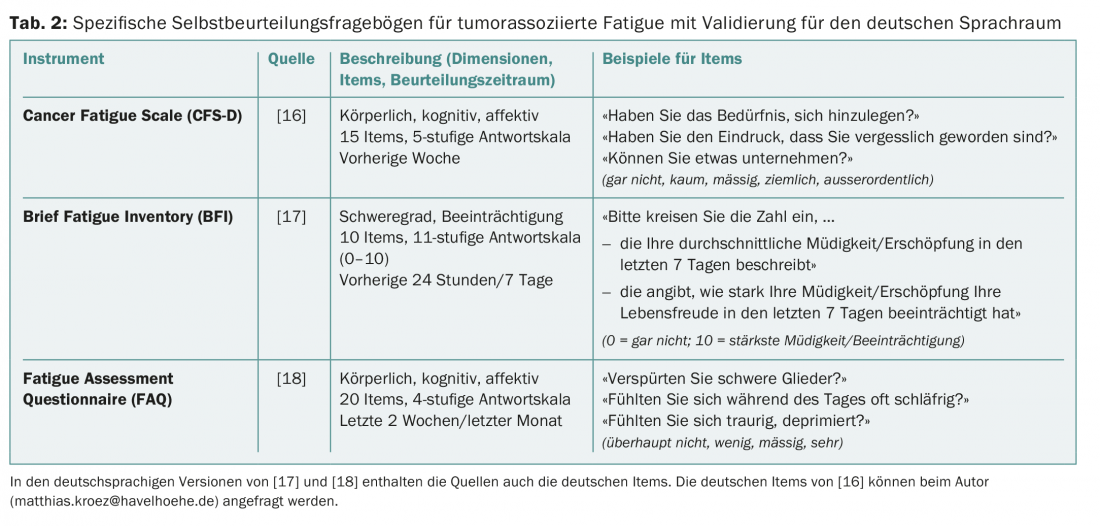

Three questionnaires, especially for the assessment of tumor-associated fatigue, have been validated for the German language area and can therefore be used to confirm the diagnosis (e.g. within an assessment procedure) (Tab. 2). All three questionnaires have good psychometric properties and can be used quickly and easily in everyday practice. In addition, the EORTC fatigue module, the EORTC QLQ-FA 13, has recently become available for use in trials [8].

ICD-10 criteria for tumor-associated fatigue

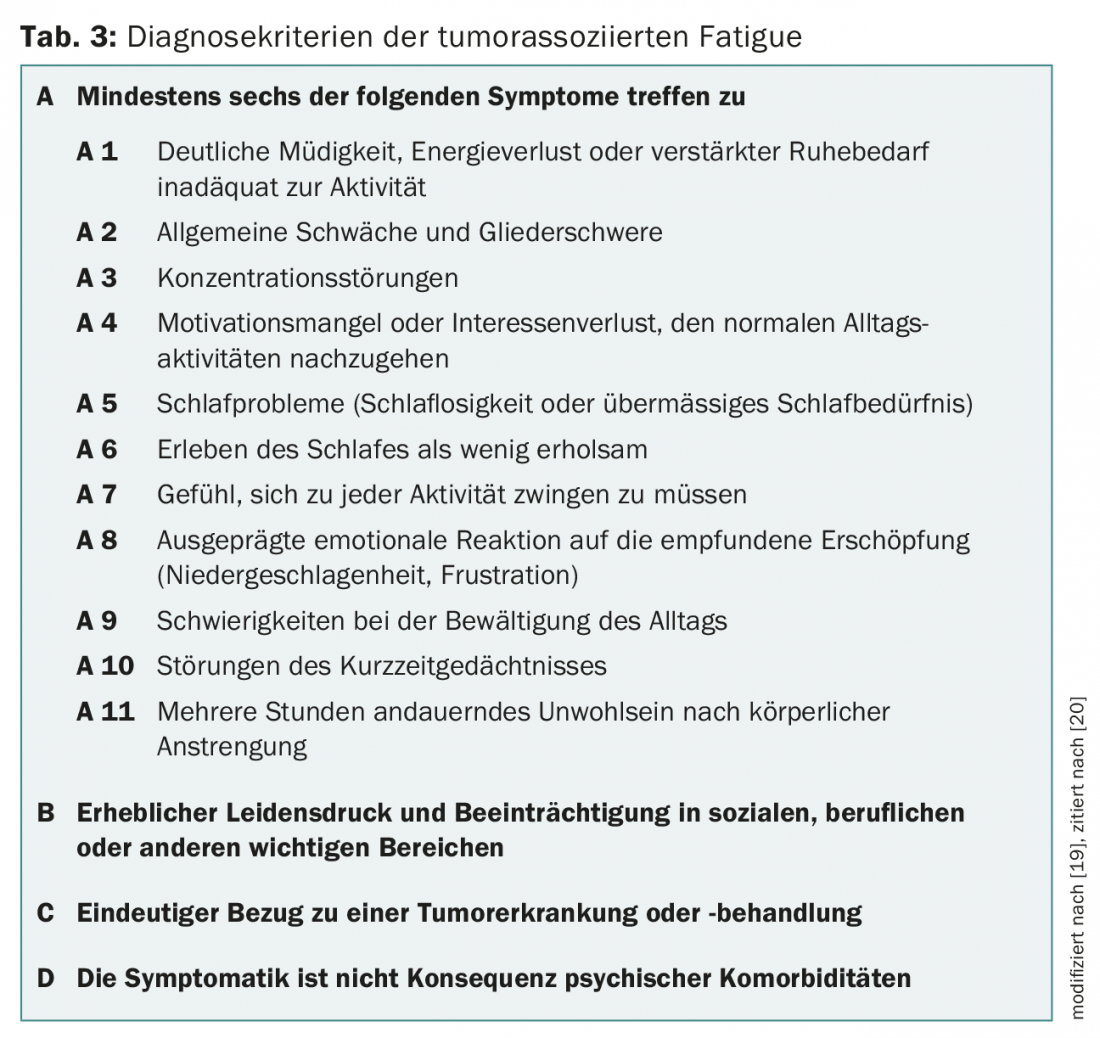

For the diagnosis of tumor-associated fatigue, ICD-10 criteria were proposed for the first time by the “Fatigue Coalition” around David Cella, which, however, have not yet been considered in the ICD despite all efforts (Table 3) [9]. Using these criteria, the diagnosis can be made if the patient affirms at least 6 of 11 symptoms and if these symptoms have occurred almost daily during a 14-day period within the last four weeks . In this case, one of the symptoms must be marked fatigue out of proportion to previous exertion. In order to be able to make the diagnosis of “tumor-associated fatigue”, the affected person must also feel limited by the fatigue and the symptoms must be a consequence of the tumor disease or its treatment.

A recent systematic review indicates that although the criteria need revision, they are reliable and valid. For example, it is unclear whether six symptoms are really required to establish a diagnosis for criterion A [10]. In addition, there is a lack of scientific evidence that the symptoms must have occurred for 14 consecutive days within four weeks. Clinical experience shows that there are patients who do not meet this criterion but still have tumor fatigue.

Fatigue diary and real-time measurement

It can be helpful for diagnosis and therapy planning to ask patients to keep a fatigue diary in which they indicate (e.g., using the scale from 0-10) at specified times of the day how tired they feel at the moment and in which everyday situation they are. This can also be done in the sense of a real-time measurement (“Ecological Momentary Assessment” [EMA]) with an “electronic diary”, in which the patient enters several times a day in response to an acoustic signal how tired he feels at the moment [11]. Personal experience with this approach is good [12].

Physical examination, laboratory and further diagnostics

Diagnosis-indicating organic findings and laboratory parameters are not known. If (detailed) history, physical examination, and orienting basic laboratory testing do not reveal underlying dysfunction, further laboratory and instrumental testing are rarely fruitful [1].

If the previous diagnostic steps have revealed indications of functional disorders, for example, these should be clarified using appropriate diagnostic methods.

Tumor fatigue or depression?

Since exhaustion is a central symptom of depressive disorders, it should always be investigated whether the patients’ complaints can be traced back to unipolar depression. To do this, one can consider, for example, whether the patient is more likely to meet ICD-10 criteria for depression or ICD-10 criteria for tumor-associated fatigue [13]. The (complementary) use of appropriate depression and CrF questionnaires can help in differentiation, as can questions about drive and motivation. In patients with tumor-associated fatigue, drive and motivation are often present, whereas these are often absent in depressed patients [4]. Typical patient statements are: “I want to, but I can’t,” but also, “I don’t want to anymore because I’ve experienced over and over that I can’t do it after all.” The question “Are you sad because you are so tired, or are there other reasons for this?” can be useful. Always keep in mind that there are patients who have both tumor-associated fatigue and unipolar depression.

Cognitive impairment

Tumor-associated fatigue may also manifest at the cognitive level. Patients affected by this complain of limitations in mental performance such as concentration and memory problems. The distinction from the “chemobrain” is fuzzy and needs scientific clarification. Even if the subjectively experienced complaints do not always correspond to the results of cognitive performance tests, the complaints should be taken seriously and clarified accordingly [14,15].

For the Working Group on Supportive Measures in Oncology, Rehabilitation and Social Medicine of the German Cancer Society (ASORS). www.asors.de

Reprinted with permission from Springer Medizin. Published in: In Focus Oncology 2013; 16(7-8): 40-44.

Literature:

- Horneber M, et al: Tumor-associated fatigue: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012; 109(9): 161-172.

- Trajkovic-Vidakovic M, et al: Symptoms tell it all: A systematic review of the value of symptom assessment to predict survival in advanced cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2012; 84(1): 13-48.

- Jason LA, et al: What is fatigue? Pathological and nonpathological fatigue. PM R 2010; 2(5): 327-331.

- Heim ME, Feyer P: The tumor-associated fatigue syndrome. Journal Oncology 2011(01): 42-47.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Cancer-Related Fatigue. www.nccn.org/professionals/ physician_gls/pdf/fatigue.pdf.

- Kirsh KL, et al: I get tired for no reason: a single item screening for cancer-related fatigue. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001; 22(5): 931-937.

- Fischer I, et al: The tumor-associated fatigue syndrome from the patients’ perspective: A qualitative study. 2012 (unpublished data).

- Weis J, et al: Development of an EORTC quality of life phase III module measuring cancerrelated fatigue (EORTC QLQ-FA13). Psychooncology 2013; 22(5): 1002-1007.

- Cella D, et al: Progress toward guidelines for the management of fatigue. Oncology (Williston Park) 1998; 12(11A): 369-377.

- Donovan KA, et al: A systematic review of research using the diagnostic criteria for cancer-related fatigue. Psychooncology 2013; 22(4): 737-744.

- Hacker ED, Ferrans CE: Ecological momentary assessment of fatigue in patients receiving intensive cancer therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 33(3): 267-275.

- Fischer I, et al: Actigraphy and ecological momentary assessment of fatigue in cancer outpatients. Oncology 2010; 33 (Suppl. 6): 179.

- Fischer I, Rüer JU: Tumor-associated fatigue or depression? neuro topical 2013; 7: 23.

- Pullens MJ, et al: Subjective cognitive dysfunction in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology 2010; 19(11): 1127-1138.

- Bartsch HH, Weis J: Cognitive decites as sequelae of oncological therapies: Diagnostics, clinical aspects, and therapeutic approaches. In Focus Oncology 2011; 14(6): 43-49.

- Kröz M, et al: Validation of the German version of the Cancer Fatigue Scale (CFS-D). Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2008; 17(1): 33-41.

- Radbruch L: Validation of the German Version of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003; 25(5): 449-458.

- Glaus A, Müller S: Measuring fatigue in cancer patients in the German-speaking world: the development of the Fatigue Assessment Questionnaire. Nursing 2001; 14(3): 161-170.

- Cella D, et al: Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence of proposed diagnostic criteria in a United States sample of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19(14): 3385-3391.

- de Vries U, et al: Tumor-related fatigue. Journal of Health Psychology 2009; 17(4): 170-184.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(3): 20-24.