The benefits of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) in the secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease are considered proven. In primary prevention, however, the evidence is controversial. The current tenor is: routine use is not recommended; if ASA is considered in high-risk groups, the expected risk of bleeding should be clarified beforehand and included in the treatment decision.

Evidence-based recommendations on this can be found in publications by various international specialist societies.

2022 Update/addendum in DEGAM guideline

The S3 guideline “Stroke” of the German Society of General Practice and Family Medicine (DEGAM) states that low-dose ASA (100 mg/day) has been shown to be neither effective nor safe in the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in three large randomized trials (ARRIVE, ASCEND, ASPREE) in otherwise healthy older people at moderately increased cardiovascular risk [1–4]. In addition to a lack of or only a very small protective effect on first-time cardiovascular events, an increase in bleeding was observed [10]. Furthermore, it is pointed out that in people with a very high cardiovascular risk, the possible primary preventive effects of ASA and the expected risk of bleeding** must be weighed up on an individual basis [1]. The standardized risk calculator “Arriba” is suggested for estimating the individual cardiovascular risk [1,8].

** as well as possible gastroprotection with medication

2022 Statement of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

This statement cites a systematic review that included 13 RCTs with a total of 161,680 patients and concluded that there is a small net benefit of ASA for the 40-59 age group with a cardiovascular risk ≥10% [5–7]. However, patients with a low bleeding risk appear to benefit to a greater extent. In over-60s, it is not recommended to routinely offer antiplatelet therapy in the primary prevention setting. Although ASA reduces the frequency of cardiovascular events in this age group, it increases the risk of gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding [5]. In addition, the USPTF recommends discontinuing ASA in people over 75 years of age who are taking it for primary prevention and deciding on an individual basis whether to continue it in people aged 60-75 who have tolerated it well to date.

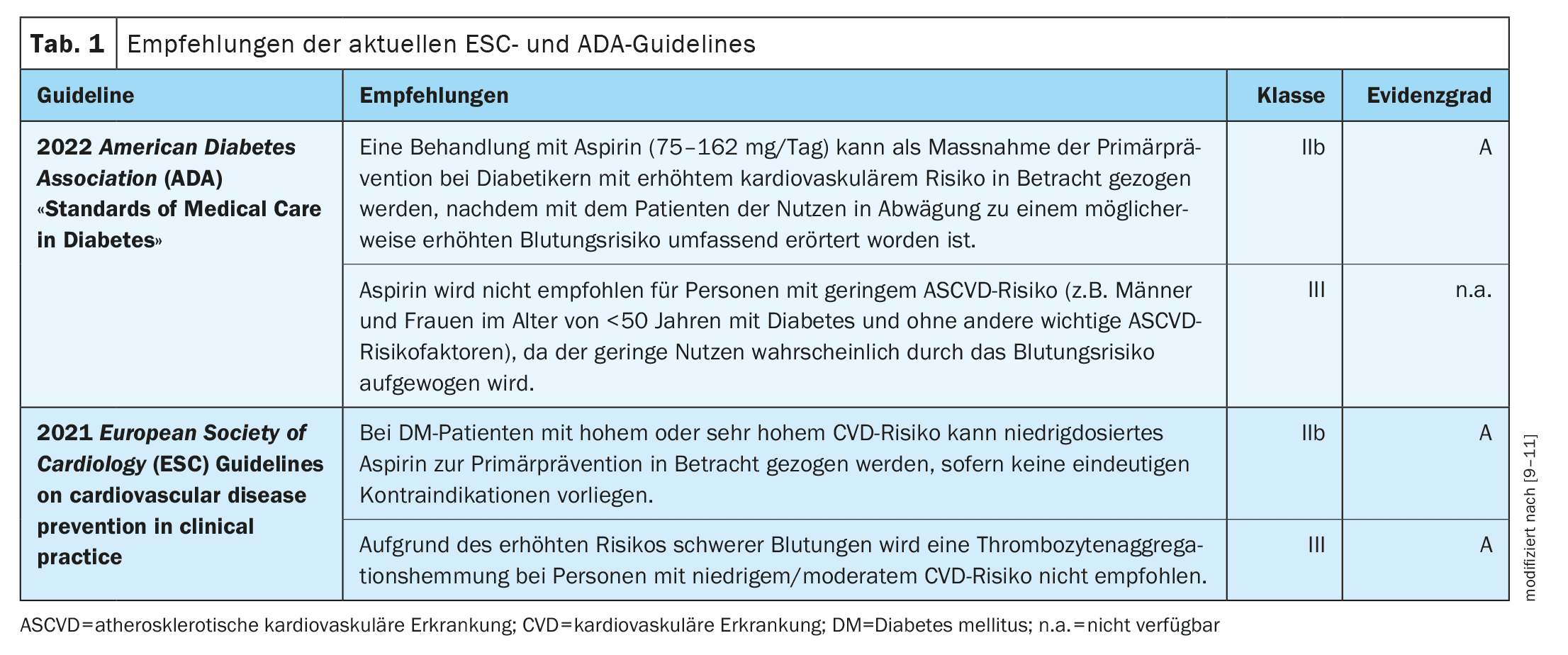

2021 Guideline of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)

They recommend that aspirin can be considered for primary prevention in patients with diabetes mellitus at high or very high cardiovascular risk, provided there are no clear contraindications [9,10]. However, they do not recommend the use of aspirin in people at low to moderate ischemic risk.

2022 Guideline of the American Diabetes Association (ADA)

The ADA suggests that aspirin (75-162 mg/day) should be considered as a primary prevention strategy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are at increased cardiovascular risk [11].

As far as peripheral artery disease (PAOD) is concerned, the latest ESC guidelines recommend the use of low-dose aspirin in asymptomatic ≥50% carotid stenosis with a low risk of bleeding [12].

However, aspirin is considered contraindicated in asymptomatic arterial disease of the lower extremities [9].

Literature:

- DEGAM: S3 Guideline Stroke. Long version: Register number 053-011. Selective update 2022/addendum, https://register.awmf.org,(last accessed 26.07.2024).

- Gaziano JM, et al: Use of Aspirin to Reduce Risk of Initial Vascular Events in Patients at Moderate Risk of Cardiovascular Disease (ARRIVE): A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2018; 392: 1036-1046.

- Bowman L, et al; the ASCEND Study Collaborative Group: Effects of Aspirin for Primary Prevention in Persons with Diabetes Mellitus. NEJM 2018; 379: 1529-1539.

- McNeil JJ, et al: Effect of Aspirin on Cardiovascular Events and Bleeding in the Healthy Elderly. NEJM 2018; 379: 1509-1518.

- Aspirin Use to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease. US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2022; 327(16): 1577-1584.

- Guirguis-Blake JM, et al: Aspirin Use to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease and Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 211. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2022. AHRQ publication 21-05283-EF-1.

- Guirguis-Blake JM, et al: Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. Published April 26, 2022. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.3337.

- Angelow A, et al: Validation of the cardiovascular risk prediction of the arriba instrument. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2022; 119: 476-482; doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0220.

- Della Bona R, et al: Aspirin in Primary Prevention: Looking for Those Who Enjoy It. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024; 13(14): 4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13144148.

- Visseren FLJ, et al: 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice, Developed by the Task Force for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice with Representatives of the European Society of Cardiology and 12 Medical Societies with the Special Contribution of the EAPC. Eur Heart J 2021; 42: 3227-3337.

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 10 Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2022. Diabetes Care 2022; 45: S144-S174.

- Aboyans V, et al: 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in Collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) Document Covering Atherosclerotic Disease of Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral, Mesenteric, Renal, Upper and Lower Extremity Arteries; Endorsed by: The European Stroke Organization (ESO), The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascul. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 763-816.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(8): 40-41 (published on 23.8.24, ahead of print)