Introduction: In vascular anomalies near the inner ear, some patients perceive pathological blood flow in the form of rhythmic ear noise. This so-called “pulsatile tinnitus” is pulse-synchronous, i.e. it correlates with the heartbeat. Typically, the frequency and intensity of tinnitus increase with increased heart rate, e.g., with increased tension and during exercise. However, ear noise is often perceived “in silence” as particularly annoying. Many of those affected therefore suffer from sleep disturbances and reduced performance during the day.

In contrast to non-pulsatile tinnitus, which usually occurs in the context of sensoneural deafness, pulsatile tinnitus often results from a structural vascular abnormality of arterial or venous origin. Arterial causes are more common and include cranial base arteriovenous dural fistulas, giant aneurysms, or stenoses. Venous causes are rare and include diverticula, anatomically raised bulbus venae jugularis, or stenosis of the transverse or sigmoid sinus. Various conservative, surgical and endovascular procedures have been established in therapy [1,2].

For the treatment of venous sinus stenosis, new nonablative endovascular therapeutic approaches have been introduced in recent years, such as endoluminal reconstruction of the sinus lumen in the affected segment by transvenous balloon-assisted stent angioplasty. The procedure has not yet been firmly established or conclusively evaluated and carries relevant treatment risks, including lethal sinus rupture. However, in carefully selected patients, endovascular treatment can be successfully performed in skilled hands. This means that they are basically individual attempts at healing, which are only applied after strict indication and frustrating exhaustion of the established therapeutic options. We describe here an illustrative case.

Symptomatic venous sinus stenosis: If a narrowing occurs in a venous sinus, e.g., due to trabeculae, septa, residual sinus vein thrombosis, or hypertrophy of Pacchioni’s granulations, blood flow becomes locally accelerated and often more turbulent. This can result in audible, pulse-synchronous sounds, pulsatile tinnitus of venous origin. Also, flow-relevant bilateral sinus stenoses or high-grade unilateral stenoses of the dominant sinus may relevantly obstruct venous outflow from the upstream brain tissue, which may be associated with brain swelling and increased intracranial pressure, or even with reduced passive CSF resorption with formation of a so-called pseudotumor cerebri.

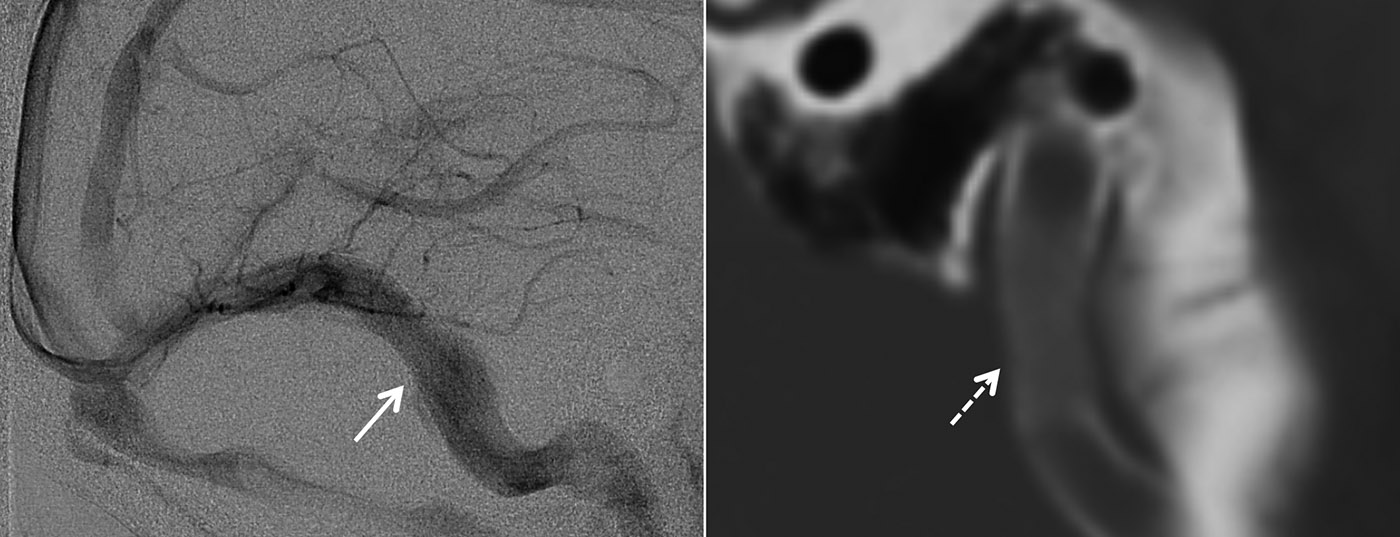

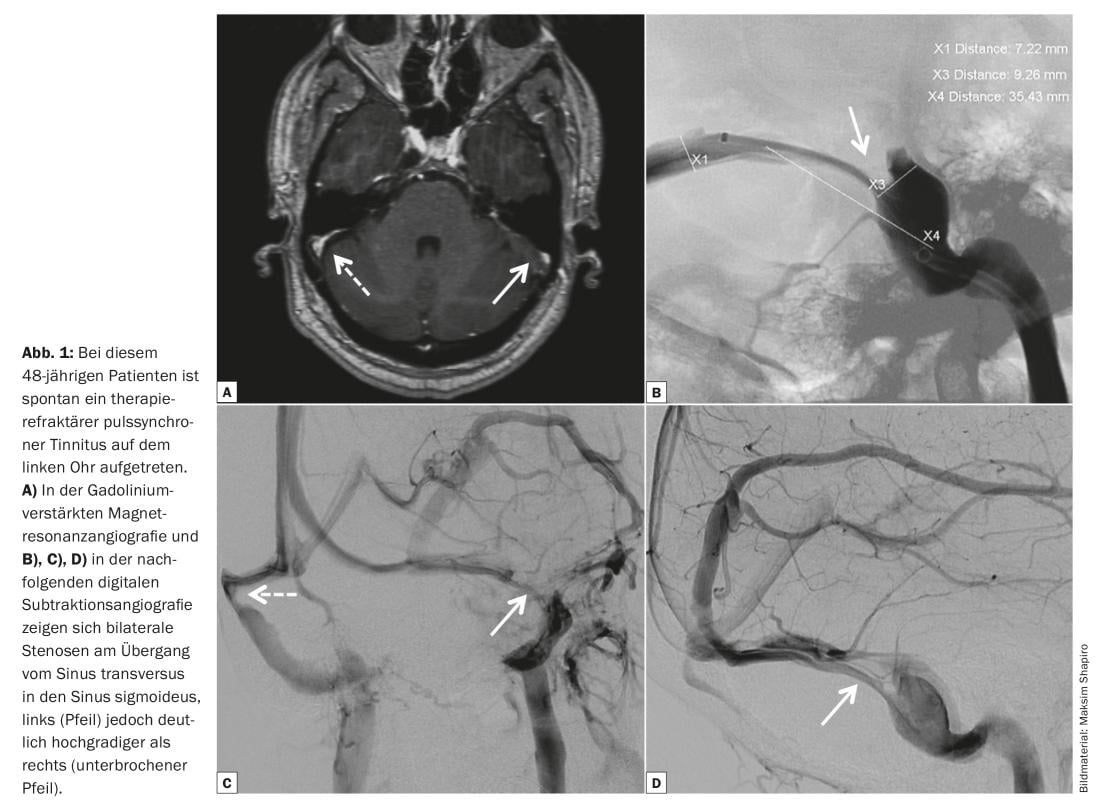

Clinical suspicion of symptomatic sinus stenosis is usually clarified in a first step with established imaging modalities such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and magnetic resonance angiography (Fig. 1A) . However, despite significant technical improvements in venous cross-sectional imaging, confirming the diagnosis often remains difficult. Diagnostic digital subtraction angiography (Fig. 1B to D), possibly with selective measurement of the pressure gradient (Fig. 2A to E), or even probatory sinus occlusion with a transvenously inserted balloon catheter can therefore help to confirm the diagnosis in some individual cases.

Established treatment modalities for pseudotumor cerebri include consistent weight loss, diuretic medications, and therapeutic lumbar puncture. In cases of refractory headache or progressive visual loss, insertion of a shunt system or surgical opening of the meninges around the optic nerve can help relieve symptoms. Ligation of the jugular vein is one of the classic treatments for refractory venous pulsatile tinnitus. However, this therapeutic option remains controversial given the significant risk of posttherapeutic sinus or cerebral venous thrombosis and the risk of secondary venous outflow obstruction.

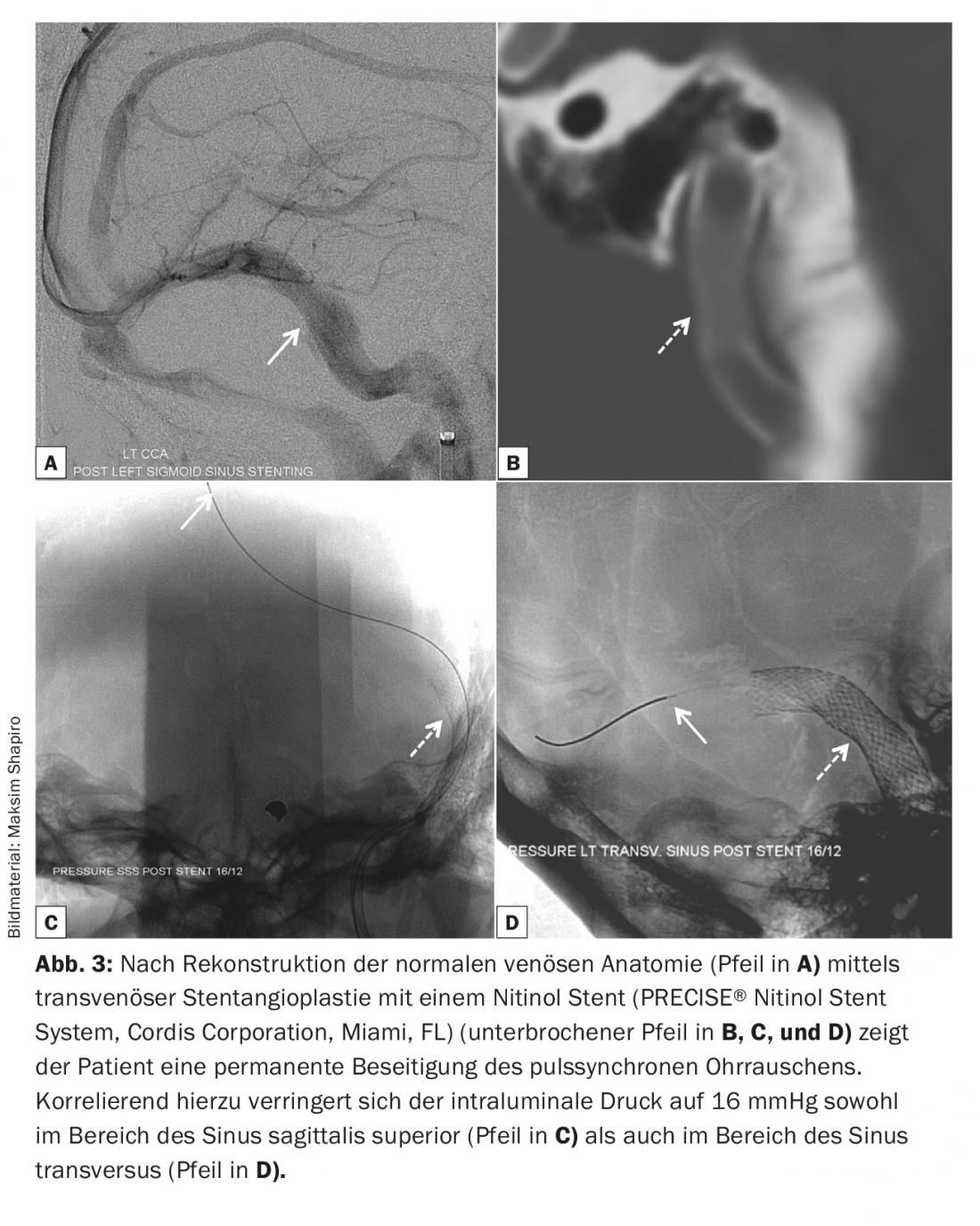

Therefore, in recent years, new nonablative therapeutic approaches have been increasingly introduced for the treatment of symptomatic sinus stenosis. One of these methods is reconstruction of the sinus lumen in the affected segment by transvenous balloon-assisted stent angioplasty (Fig. 3A to B). In patients with pseudotumor cerebri, the goal of transvenous angioplasty is to reduce the venous pressure gradient by restoring normal venous anatomy, thereby normalizing CSF reabsorption. In the patient with venous pulsatile tinnitus, transvenous angioplasty aims to lower the venous pressure gradient and abolish turbulent blood flow to achieve permanent elimination of ear noise (Fig. 3C through D).

Currently, reliable data on the safety and efficacy of venous angioplasty or stent angioplasty are not available. As described at the beginning, this is currently still an experimental therapeutic option for selected patients. It is also important to note that transvenous stenting requires both dual antiplatelet therapy (e.g., ASA for life and clopidogrel for six months) and temporary oral anticoagulation (e.g., Marcoumar® for six months) to prevent in-stent occlusion by activating plasmatic hemostasis.

Literature:

- Lasjaunias P, Berenstein A, ter Brugge KG: Surgical Neuroangiography. Vol. 2nd Edition. Springer Verlag 2004.

- Yasargil MG: Microneurosurgery In 4 Volumes. Thieme Verlag 1994.

Further reading:

- Hofmann E, et al: Pulsatile tinnitus: Imaging and differential diagnosis. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 2013; 110(26): 451-458.

- Biousse V, Bruce BB, Newman NJ: Update on the pathophysiology and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012 May; 83(5): 488-494.

- Baomin L, Yongbing S, Xiangyu C: Angioplasty and stenting for intractable pulsatile tinnitus caused by dural venous sinus stenosis: a case series report. Otol Neurotol 2014 Feb; 35(2): 366-370.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(4): 28-30.