According to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guideline updated last year, heart failure is classified into HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF according to left ventricular ejection fraction. Regarding drug therapy, early combination therapy with ACE-i, ARNI, MRA, and SGLT-2-i has recently been recommended for all patients. The fact that HFpEF patients can also benefit from therapy with SGLT-2 inhibitors is demonstrated in particular by new clinical trial data published shortly after the guideline was published.

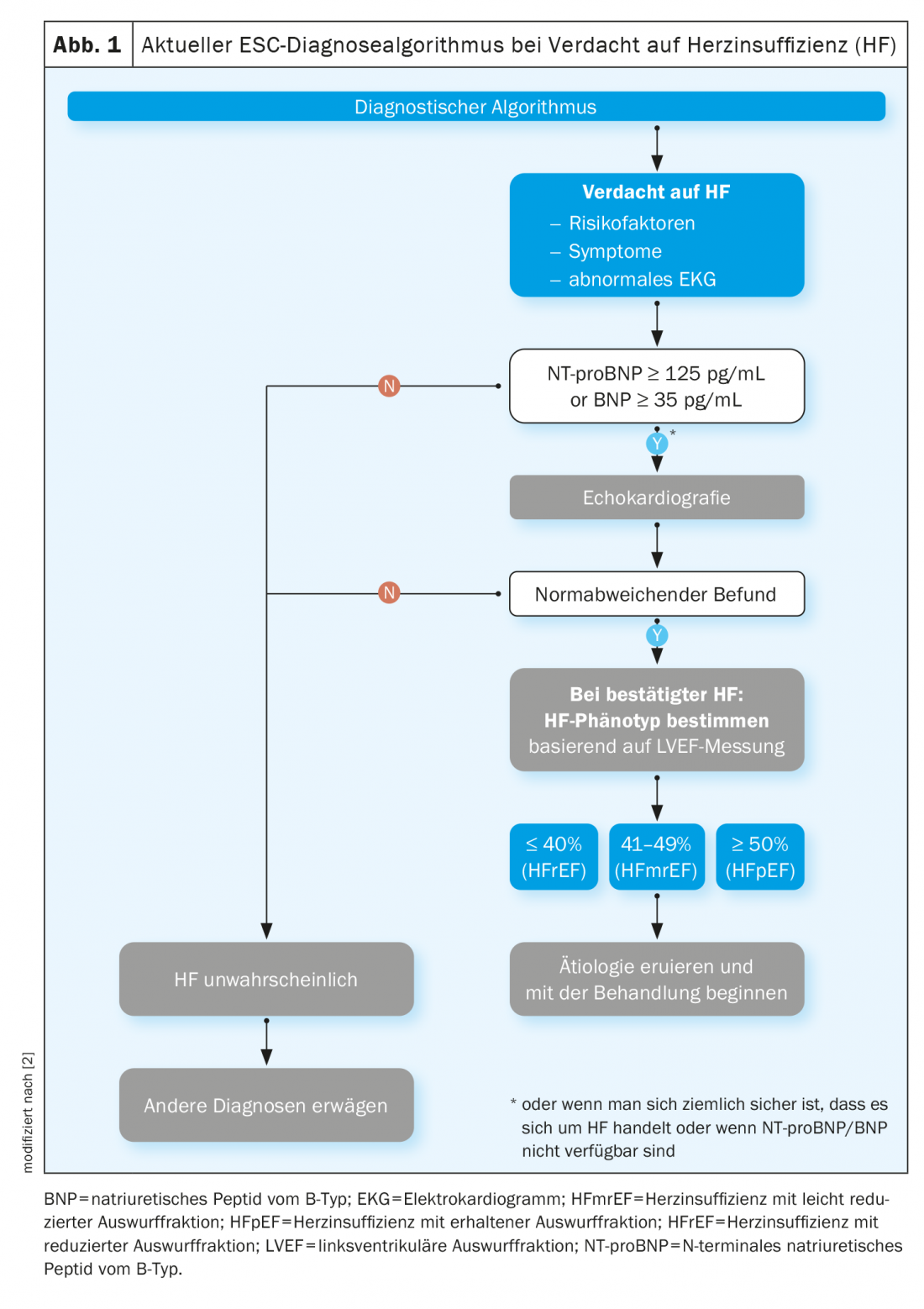

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome triggered by structural and functional cardiac changes and is associated with a reduction in ejection fraction or an increase in filling pressures, both at rest and during exercise. The diagnosis of heart failure requires the presence of symptoms as well as objective evidence of cardiac dysfunction (Fig. 1). Typical clinical signs include shortness of breath, fatigue, and ankle swelling. After initial diagnosis, heart failure patients are hospitalized on average once a year [9]. In the context of demographic developments and an increase in comorbidities, experts predict that the number of hospital admissions could rise significantly [7,8]. Atrial fibrillation, high BMI, and elevated HbA1c levels or low glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) are strong predictors of hospitalization [10]. “Our goal must be to identify patients at an early stage in order to be able to prevent progression to severe heart failure,” explained Prof. Sabine Genth-Zotz, MD, Chief of Medicine, Marienhaus Klinikum Mainz [1].

What is the recommended diagnostic algorithm?

First, a careful history should be taken. The current ESC guideline indicates that the presence of heart failure is more likely in patients with a history of myocardial infarction, or in those with arterial hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, alcohol abuse, or chronic kidney disease. It is essential to ask about physical resilience and any episodes of shortness of breath. In the clinical examination that follows the anamnesis, particular attention should be paid to edema and auscultation of the heart and lungs (gallop rhythm? signs of congestion?), as Prof. Genth-Zotz emphasizes. The next step in the ESC diagnostic algorithm is an electrocardiogram (ECG). An unremarkable ECG finding makes the presence of heart failure unlikely [5]. In contrast, abnormalities such as atrial fibrillation, Q waves, left ventricular hypertrophy, and a dilated QRS complex increase the likelihood of the presence of heart failure. In this case, as shown in Figure 1 , further investigation is indicated. What should be recorded by laboratory diagnostics? The guideline recommends electrolytes, serum urea, creatinine, and complete blood count. For differential diagnostic purposes, liver and thyroid function tests may also be useful. According to the current ESC guideline, natriuretic peptides play a very important role [2]. If the NT-proBNP value is above 125 pg/ml, further diagnostics should be performed; the same applies to BNP ≥35 pg/ml. If the measured values are below that, the probability of heart failure is low, adds Prof. Genth-Zotz. If one does not have the opportunity to collect natriuretic peptides, the speaker recommends proceeding directly to echocardiographic assessment [1].

Is it HFrEF, HFmrEF or HFpEF?

According to the ESC, if echocardiography reveals pathologic findings, heart failure (HF) can be divided into these three entities based on ejection fraction:

- HFrEF (“HF with a reduced ejection fraction”): LVEF ≤40 %

- HFmrEF (“HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction”): LVEF 41-49%

- HFpEF (“HF with preserved ejection fraction”): LVEF ≥50%

Analyses of the ESC long-term registry of outpatient heart failure patients indicate that 60% are affected by HFrEF, 24% by HFmrEF, and 16% by HFpEF [6]. Younger, male individuals are common among patients with HFmrEF. Coronary artery disease is present in about half of the cases, whereas non-cardiac comorbidities are rare. The treatment of HFmrEF patients is structured very similarly to HFrEF sufferers. HFpEF, on the other hand, tends to be a special patient population, usually older patients, often women, and often noncardiovascular comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, renal insufficiency) are present.

Paradigm shift: four pillars of drug therapy

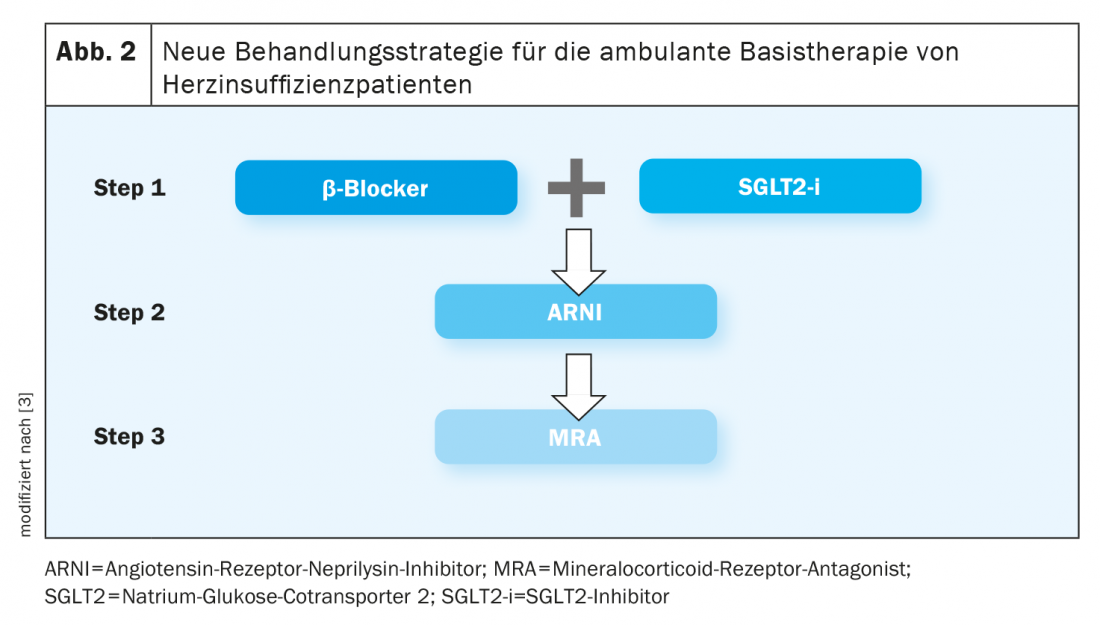

The drug treatment proposed by the guideline is based on the terminological classification of HFrEF, HFmrEF, or HFpEF [2]. A new recommendation is that initially all heart failure patients can receive an ACE inhibitor (ACE-I), an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), a beta blocker, a mineral corticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), and an SGLT2 inhibitor (SGLT2-i) (Fig. 2). Ideally, all these drugs should be administered within four weeks. However, since the hospitalization period is usually only 4-5 days, the clinicians generally make a recommendation to the physicians in charge of outpatient follow-up on what should be titrated and at what dose, the speaker explained. In patients after cardiac decompensation, special care must be taken with titration, and close monitoring is very important in the presence of comorbidities.

SGLT-2-i: suitable for most patients – also in HFpEF.

What to consider in patients with hypotension was formulated by McMurray and Packer in an article published in 2021 [3]. Accordingly, in patients with an arterial blood pressure<100 mmHg, one can start with an angiotensin receptor blocker. Furthermore, the use of SGLT-2 inhibitors is safe in this regard. “We have seen in different studies that the blood pressure reduction with initiation of an SGLT-2 inhibitor is very marginal,” explained Prof. Genth-Zotz [1]. That HFpEF patients also benefit from this therapeutic option is shown by the results of the EMPEROR-Preserved study, which was published shortly after the ESC guideline [4]. This indicates that empagliflozin can effectively reduce the risk of heart failure-related hospitalization in HFpEF patients. “In heart failure, no matter what ejection fraction we’re talking about, we can use empagliflozin: very simply at a dose of 10 mg once a day,” the speaker summarized [1].

What should always be kept in mind regardless of this are the diuretics – these do play a role in most patients, especially in decompensation, but: “If the patient is recompensated, you should always make sure that you reduce the diuretics, even in the office-based setting,” emphasizes Prof. Genth-Zotz [1]. Moreover, the question of whether there are other pathophysiological changes that can be addressed, such as left bundle branch block, should not be neglected. And if patients have high-grade mitral regurgitation or aortic valve stenosis, this should also be treated, and the same is true for revascularization in severe coronary disease, the speaker elaborated.

Congress: DGIM Internistenkongress

Literature:

- “Guideline Update: What’s New in Heart Failure,” Prof. Sabine Genth-Zotz, MD, 128. Congress of the German Society for Internal Medicine (DGIM), 30.04.2022

- McDonagh TA, et al: ESC Scientific Document Group: 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2022; 24(1): 4-131.

- McMurray JJV, Packer M: How Should We Sequence the Treatments for Heart Failure and a Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Redefinition of Evidence-Based Medicine. Circulation 2021; 143(9): 875-877.

- Anker SD, et al; EMPEROR-Preserved Trial Investigators. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2021; 385(16): 1451-1461.

- Mant J, et al: Systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of diagnosis of heart failure, with modelling of implications of different diagnostic strategies in primary care. Health Technol Assess 2009; 13:1-207, iii.

- Chioncel O, et al: Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19: 1574-1585.

- Savarese G, Lund LH: Global public health burden of heart failure. Card Fail Rev 2017; 3: 7-11.

- Al-Mohammad A, et al: Chronic Heart Failure Guideline Development Group. Diagnosis and management of adults with chronic heart failure: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2010; 341: c4130.

- Barasa A, et al: Heart failure in young adults: 20-year trends in hospitalization, aetiology, and case fatality in Sweden. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 25-32.

- Mosterd A, Hoes AW: Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart 2007; 93: 1137-1146.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(7): 30-32