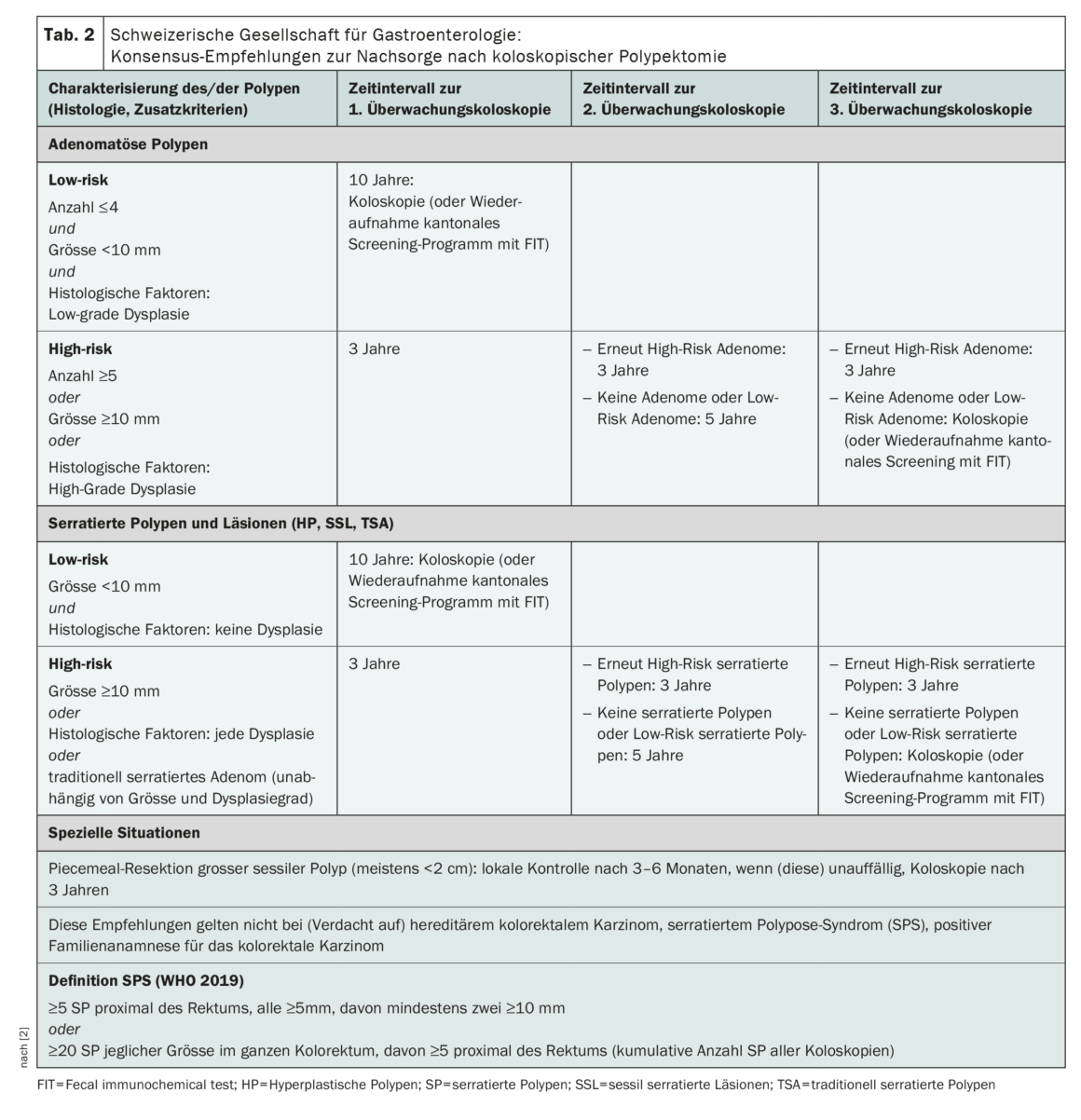

The primary goal of colonoscopic surveillance is to reduce the risk of subsequent colorectal cancer. The most recent version of the consensus recommendations of the Swiss Society of Gastroenterology was published in 2022 and provides guidance on evidence-based colonoscopy intervals and other clarifications.

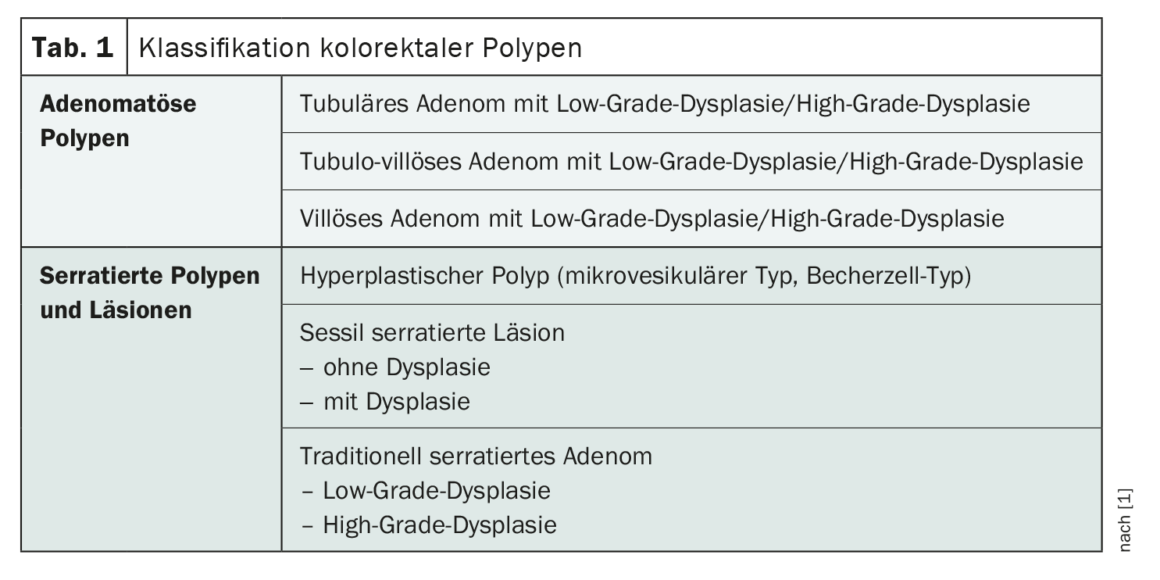

A proportion of patients with colorectal polyps detected at baseline colonoscopy (Table 1) are at increased risk for metachronous development of advanced polyps or colorectal cancer (CRC) [1]. Stratification for CRC risk is based on baseline colonoscopy findings, i.e., subtype, size, and number of polyps, as well as their location and histologic characteristics. The Swiss consensus recommendations published in 2022 replace the version published in 2014 and await some changes compared to the previous version [1,2]. Their application is to be adapted in each case to the individual situation of the patient, taking into account local expertise [1].**

** These revised recommendations cannot be applied in cases of suspected or confirmed hereditary syndrome (familial adenomatous polyposis [FAP], hereditary non-polyposis colon carcinoma [HNPCC] etc.) and positive family history for colorectal carcinoma (CRC).

Adenomatous polyps: High-risk vs. low-risk adenomas

Among the most important innovations for follow-up after removal of adenomatous polyps is the differentiation into situations with high-risk or low-risk adenomas with control after three or ten years, respectively (Table 2) [1]. Low-risk adenomas are defined by size (<10 mm), multiplicity (≤4), and absence of high-grade dysplasia. The presence of villous histology is no longer considered for risk stratification (new data, substantial interobserver variability). In contrast, recent studies confirm a significantly increased CRC risk for patients with high-risk lesions (size ≥10 mm, ≥5 polyps, evidence of high-grade dysplasia), justifying the indication to perform a follow-up colonoscopy after three years [1,3,4]. If a low-risk situation is present, either a colonoscopy can be performed again after ten years or the cantonal screening program can be resumed using FIT.

What is also an innovation in the revised recommendations is that for the first time colorectal cancer screening is taken into account: after polypectomy, control can be performed not only colonoscopically but also with a fecal immunochemical test FIT [1].

The recommendation to perform an endoscopic control of the resection site after 3-6 months after piecemeal resection (usually from a polyp size >2 cm) or in case of uncertainty regarding the completeness of the polyp removal and, if this does not show a recurrence, to perform another one after three years remains valid [1].

Serrated polyps

Hyperplastic polyps (HP), sessile serrated lesions (SSL), and traditionally serrated adenomas (TSA) are subsumed under the umbrella term “serrated polyp” (SP), and their malignant potential and association with the development of metachronous high-risk adenomas varies [1]. According to data, small SP (<10 mm) without dysplasia have a CRC risk comparable to a few low-risk adenomas [5].

Accordingly, colonoscopic surveillance or re-enrollment in the screening program for low-risk SP is recommended after ten years (Table 2). In contrast, there are serrated polyps that have a CRC risk comparable to high-risk adenomas [5–7]. High-risk SP are characterized first by size (≥10 mm) and second by evidence of dysplasia [1]. For this subtype of serrated polyps, follow-up colonoscopy after three years is recommended, analogous to high-risk adenomas.

In patients with traditionally serrated adenomas (TSA), colonoscopic surveillance is recommended after their removal regardless of size, number, and degree of dysplasia at three years.

If serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) is suspected or confirmed, these recommendations should not be used. According to WHO, SPS is present when there are many (≥20 of any size, of which ≥5 are proximal to the rectum) or multiple larger SPs (at least 5 SPs ≥5 mm proximal to the rectum, of which at least two are ≥10 mm) [1].

Malignant polyp with pT1 carcinoma

In pT1 carcinomas, curative endoscopic resection of tumor budding is among the innovations [1]. This is defined as the detection of individual tumor cells or tumor cell groups (up to four tumor cells) at the tumor invasion front. Several studies in recent years have shown that tumor budding is a prognostically independent morphologic biomarker and is associated with tumor progression [8].

The other criteria remained unchanged. For a pT1 lesion to be classifiable as low-risk carcinoma, all criteria must be met. It is recommended that all high-riskpT1 cancers present to the tumor board.

Literature:

- Truninger K, et al.: Revidierte Konsensus-Empfehlungen. Swiss Med Forum 2022; 22(2122): 349–355.

- «Konsensus-Empfehlungen zur Nachsorge nach koloskopischer Polypektomie», https://sggssg.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Empfehlungen/Nachsorge_

kolo_Polypektomie_DE.pdf, (letzter Abruf 21.04.2023) - Cross AJ, et al.: Colorectal cancer risk following polypectomy in a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study: an evaluation of the 2020 UK post-polypectomy surveillance guidelines. Gut 2021; 0: 1–14.

- Duvvuri A, et al.: Detection of Low-Risk or High-Risk Adenomas, Compared With No Adenoma, at Index Colonoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2021; 160: 1986–1896.

- He X, et al.: Long-Term Risk of Colorectal Cancer After Removal of Conventional Adenomas and Serraed Polyps. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 852–861.

- Holme O, et al.: Long-term risk of colorectal cancer in individuals with serrated polyps. Gut 2015; 64: 929–936.

- Erichsen R, et al.: Increased risk of colorectal cancer development among patients with serrated polyps. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 895–902.

- Lugli A, et al.: Tumor budding in solid cancers. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020; 18: 101–115.

InFo ONKOLOGIE & HÄMATOLOGIE 2023; 11(2): 34–35

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(5): 18–20