It is felt that cases of severe asthma have been steadily increasing in recent years. This may be due in no small part to the development of biologics, which now make it possible to initiate effective therapy in response to a diagnosis. In fact, however, there seem to be far fewer severe asthmatics than difficult-to-treat patients. However, identifying and distinguishing these patient groups from one another requires work.

The definition of severe asthma has actually been clearly formulated since the GINA Report 2022 [1]: Despite high dose of ICS/LABA (or if reduced), at least one of the following applies to the patient or would apply if therapy were reduced:

- Poor symptom control: ACQ >1.5, ACT <20

- Frequent seizures: ≥2 OCS episodes/year (>3 days).

- Severe asthma attack: hospitalization, ICU, or “required intubation” in the past year

- Airway obstruction: FEV1 <80%PB predicted

According to the GINA guidelines, to meet the definition of severe asthma, one needs high-dose ICS/LABA. However, looking at the preferred treatment pathway (Track 1) of the GINA recommendations, this is not a given, as only a medium maintenance dose of ICS/formoterol is recommended on Step 4. Only the alternative track 2 mentions the ICS/LABA combination in high dose (Fig. 1) .In the recently published specialist S2k guideline [2] of the DGP, this has already been adapted compared to GINA and the NVL.

Difficult to treat, on the other hand, is defined as asthma that is

- is uncontrolled despite a medium- or high-dose ICS with a second controller

- Requires high-dose therapy to maintain good symptom control and reduce the risk of exacerbation

Furthermore, in many cases, modifiable factors such as (in)correct inhalation technique, poor adherence, comorbidities, or a possible misdiagnosis must first be clarified before a final determination of severe or difficult-to-treat asthmacan be made.

“If the patient must now require a high dose of ICS/LABA for difficult-to-treat asthma in order to have symptom control and avoid the risk of exacerbation, one must state that this description applies equally to severe asthma,” noted Prof. Dr. Marco Idzko, Clinical Department of Pulmonology, University Hospital of Vienna (A) [3]. “So we see, even in GINA, there is no clear difference between severe asthma and difficult-to-treat asthma.”

Number of severe asthmatics only 1%?

An Australian study [4] looked at more than 1.8 million asthmatics without considering symptom control, inhaler technique, comorbidities, or adherence, but only considered prescription numbers (Fig. 2) . If a patient received a high-dose ICS/LABA at least four times in the past six months, they were classified as Difficult-to-treat asthmatics. If such a patient was additionally prescribed an oral glucocorticoid dose sufficient to cover two exacerbations, he was considered uncontrolled difficult-to-treat and thus severe asthmatic. This group represented 2.6% of the total population. “If we factor out comorbidities and lack of adherence, that leaves maybe just 1% severe asthmatics,” Prof. Idzko opined.

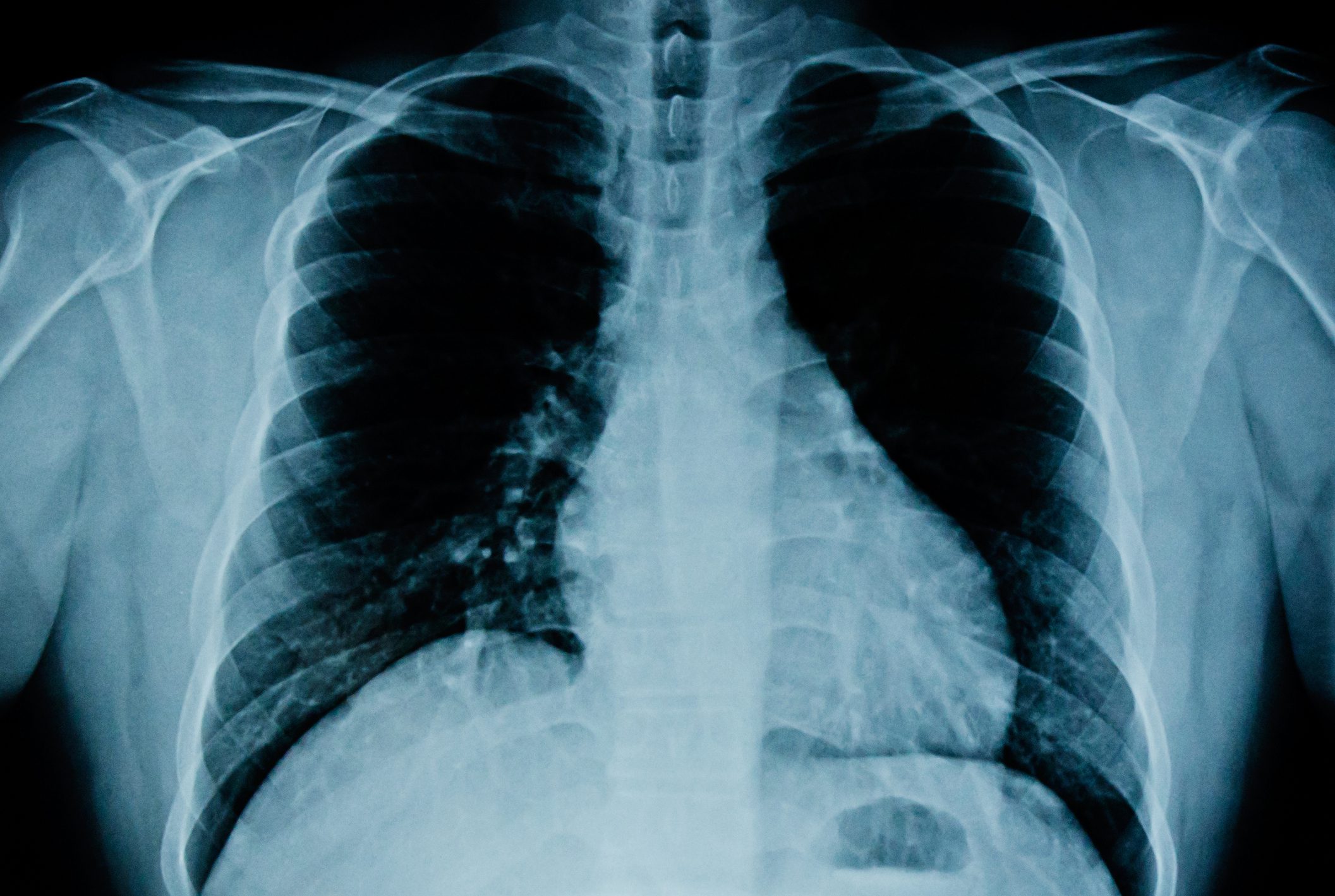

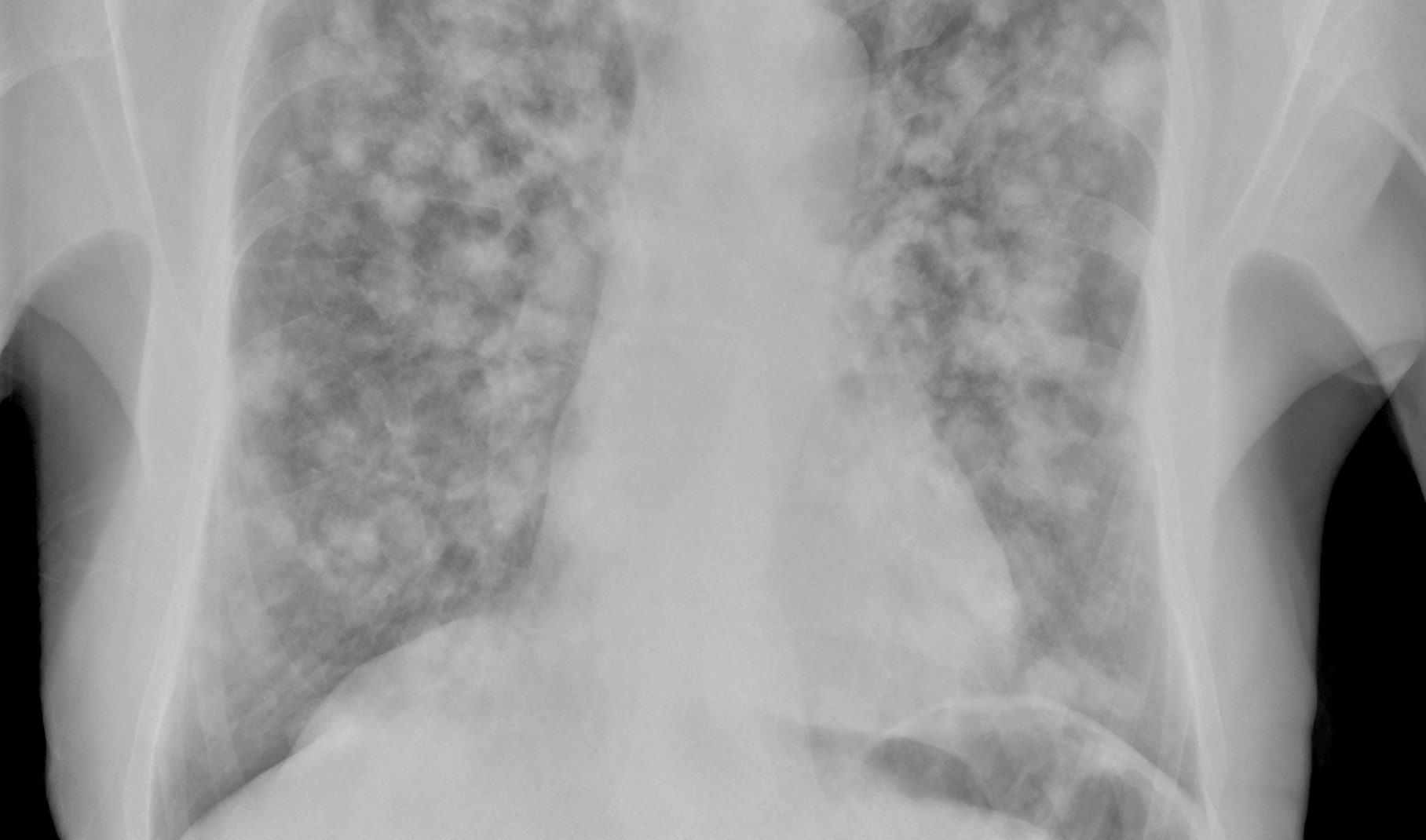

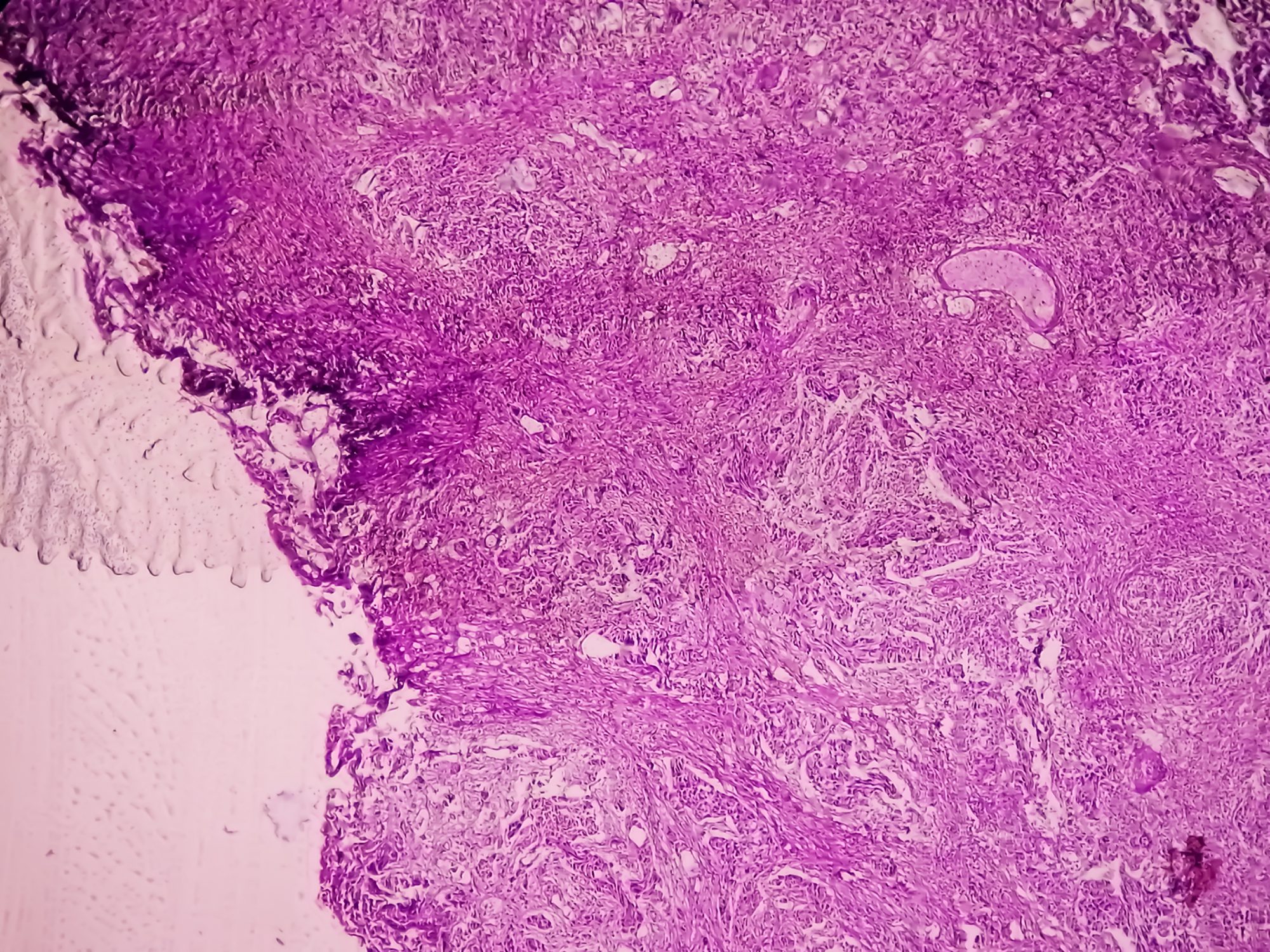

On the question of how to proceed with one’s patients, the expert again recalled the guidelines: “Please internalize what we would have to do according to GINA before we are even allowed to think about a biologic. That’s a lot of work!” This starts with checking the inhalation technique, adherence and comorbidities such as GERD, chronic rhinosinusitis or OSA, continues with the clarification of a possible overuse of the SABA reliever and ends with potential drug side effects. This is followed by optimization of therapeutic management including incorporation of non-pharmacological interventions (smoking cessation, weight loss, influenza or COVID-19 vaccination). Only when all these factors have been checked and the disease is still uncontrolled after 3-6 months, one could speak of severe asthma. “And then it really starts: autoimmune diseases must be clarified, IgG, IgE, IgM, a CT must be made, differential diagnoses such as COPD, bronchiectasis, CF, VCD, asthma cardiale and tumors must be excluded, as well as diseases without regular obstructive ventilation disorder, including chronic bronchitis, sarcoidosis, pneumothorax eosinophilic bronchitis or bronchiolitis.” Leaving the cardiologist aside, according to the new specialist guideline [2], from the pneumological side alone, every patient should have a CT chest and a measurement of the diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), the complete rheumatoid serology should be taken, and if necessary a bronchoscopy with BAL and biopsy should be performed.

In summary, it is understandable to give the patient a biologic right away instead of going through the procedure described, especially since biologics also work well in difficult-to-treat patients. But when guidelines and treatable traits are taken into account, Prof. Idzko said the number of severe asthmatics is far below the 5-10% often reported. When a patient presents with uncontrolled asthma, the first thing to think about is Difficult-to-treat asthma – “severe asthma is basically a diagnosis of exclusion and needs an intensive work-up before we can really make the diagnosis.”

Congress: DGP 2023

Literature:

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (2022 update); https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-07-01-WMS.pdf.

- Lommatzsch M, Criee CP, De Jong C, et al.: S2k-Leitlinie zur fachärztlichen Diagnostik und Therapie von Asthma 2023, herausgegeben von der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin e.V.; März 2023; AWMF-Registernr.: 020-009.

- Idzko M: Vortrag «Schweres Asthma: Nicht so häufig, wie man denkt» im Rahmen des Symposiums «Seltene Lungenerkrankungen: der Ursache auf der Spur». 63. Kongress der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin e.V. in Düsseldorf, 1.04.2023.

- Wark PAB, Hew M, Xu Y, et al.: Regional variation in prevalence of difficult-to-treat asthma and oral corticosteroid use for patients in Australia: heat map analysis. Journal of Asthma 2023; 60: 727–736; doi: 10.1080/02770903.2022.2093217.

InFo PNEUMOLOGIE & ALLERGOLOGIE 2023; 5(2): 40–42