UCV results from chronic overpressure in the venous system of the lower extremity. The correct diagnosis is made by a detailed history, clinical examination and ultrasound examination. The foundation of successful ulcer treatment is the reduction of ambulatory venous hypertension through compression therapy. Local treatment includes regular debridement of the wound, control of the amount of exudate, lowering of the bacterial load and creation of an ideal climate for healing (moist wound treatment by choosing appropriate dressings adapted to the stage of healing). In the absence of successful healing and verification of the correct diagnosis, a surgical approach with extensive debridement/ulcer excision and, if necessary, simultaneous treatment of the underlying phlebopathology may be useful as a forward strategy. After the healing of the UCV, the correction of the phlebopathology in the sense of recurrence prophylaxis should be aimed at in any case, respectively. establish permanent compression therapy and pay the utmost attention to skin care.

Among the differential diagnoses in patients with leg ulcers, venous leg ulcer (UCV) is the most common. According to the literature, approximately 50-70% of patients with leg ulcers suffer from causative chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) [1]. The prevalence for advanced CVI with UCV in the population is approximately 1-1.5%.

Origin of the UCV

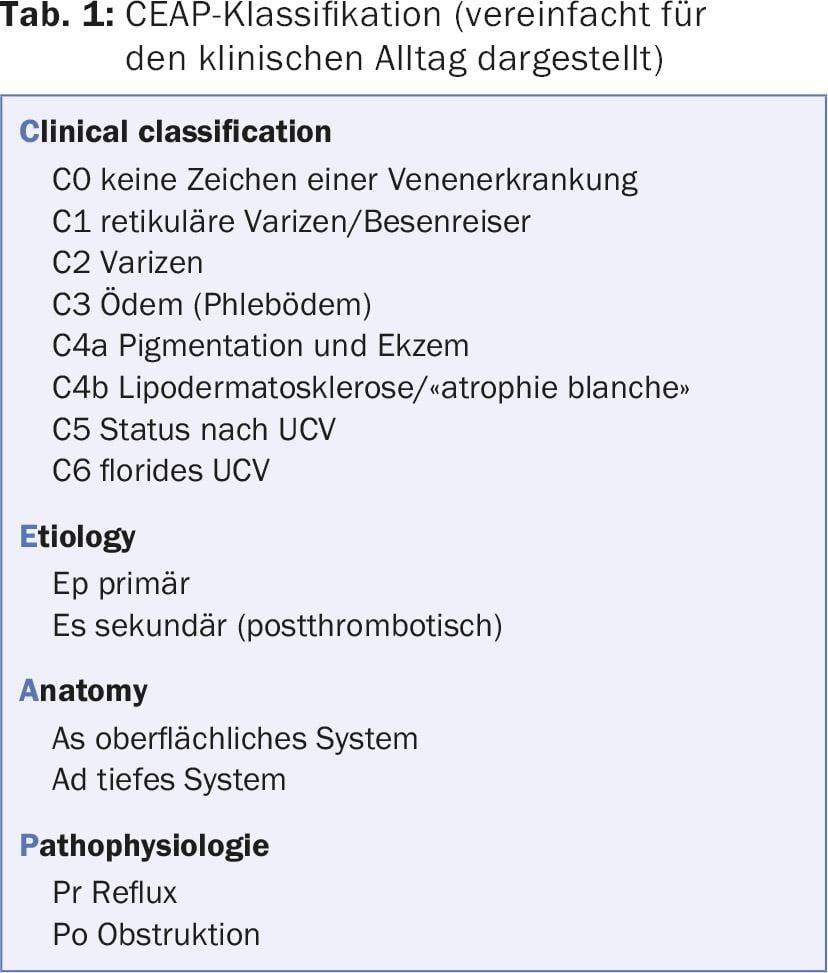

Underlying the development of chronic venous insufficiency is pathology in the superficial and/or deep venous system. While reflux in the superficial venous system (in the narrower sense varicosis) only slowly leads to the development of a higher-grade CVI (CEAP 4-6, Tab. 1), functional and usually secondary disorders in the deep venous system (postthrombotic syndrome) lead to the clinical manifestation of a CVI much more rapidly [2]. It is not clear whether reflux or obstruction is more conducive to the development of CVI. Both conditions, reflux and obstruction, are culprits in venous hypertension. In this context, one also speaks of ambulatory venous hypertension, meaning that venous pressure does not decrease even during exercise, i.e., the various mechanisms that serve to return venous blood and thus lower the pressure in the veins are diminished or no longer effective (calf muscle pump, squeezing of the plantar plexus, respiratory and cardiac suction phenomena, among others) [3]. Fluid and protein leakage from the capillaries, complex inflammatory processes and the corresponding accumulation of specific inflammatory cells (macrophages and monocytes) result in a breakdown of the physiological skin and subcutaneous supply of nutrients and oxygen [4].

Clinic

UCV varies in pain depending on its location and not infrequently results from an initial scratching injury to the skin. Ambulatory hypertension, accompanied by the metabolic changes described above, leads to itching that sufferers try to relieve with scratching. Typically, the ulcers are found in the so-called gaiter zone, i.e. proximal to the malleolar plane, somewhat clustered medially. The integument shows the typical signs of long-standing venous congestion with ocher-colored areas (“purpura dermite jaune d’ocre”) and whitish, sclerosed areas (“atrophie blanche”) (Fig. 1).

The lesions, which are only small at the beginning, can become larger very quickly. Numerous home remedies have an unfavorable effect on the course. Extracts from plants or alcohol wraps further destabilize the skin and the wound edge, intensify the inflammatory processes and can lead to allergic reactions. The severity of the inflammation finds clinical expression in the amount of exudate. Ulcers with a high bacterial load also exude more fluid. Often, severe exudation is more decisive for the loss of quality of life than the local pain problem.

Diagnosis

Because the development of chronic venous insufficiency takes place over a long period of time, there are usually clear indications in the patient’s medical history. In the foreground is the question of previous venous thrombosis and previous interventions on the superficial venous system as an expression of superficial venous insufficiency. In elderly patients, a thrombotic event in the past is not always remembered or it went unnoticed without appropriate diagnosis and therapy. If the history and clinical presentation of the ulcer support the suspicion of UCV, further phlebologic workup is performed with the goal of balancing the causative phlebologic pathology/pathophysiology. The gold standard for the examination of the venous system is color-coded duplex sonography (FKDS). the compression sonography. Although cw Doppler examination alone allows the suspicion of venous disease to be postulated, it is not sufficient in terms of reproducibility and accuracy [5,6]. In the case of ulcerations that have been present for years, a possible degeneration should always be considered and biopsy should be performed to exclude it.

Therapy

Because UCV results from ambulatory venous hypertension, the primary causative therapeutic approach is to counteract this venous hypertension. This is done conservatively by prescribing adequate compression. How much compression is “adequate” is always a matter of controversy. Currently, at least a compression stocking of compression class II (23-32 mmHg) should be worn, but there is a tendency that stockings with a lower contact pressure also have a sufficient effect. It should be borne in mind that simultaneous severe restriction of arterial blood flow (PAVK) must be excluded, especially in elderly patients. With palpable foot pulses or an ABI of >0.8, compression therapy is readily feasible.

The invasive treatment option focuses on surgical correction of venous hypertension. However, the treatment of the functionally disturbed venous system does not contribute to a faster healing of UCV, but should be aimed at as recurrence prophylaxis. Here, the treatment options on the superficial venous system pursue the elimination of the recirculation circuit (classical surgery, endoluminal surgery, sclerotherapy). Therapeutic options on the deep venous system are less established and require careful and strict indication (valve reconstruction, valve transposition).

Local therapy is guided by the current comprehensive recommendations for the management of chronic wounds. After measuring and documenting the wound and its condition in as standardized a manner as possible, local treatment should be based primarily on bacterial colonization and the degree of exudation. If local infection is clinically suspected, microbiological testing is sought to identify the pathogenic germs. A correctly performed smear test can lead to usable results, but is inferior to wound biopsy in terms of informative value [7].

Instead of topical antibiotics, local antiseptics and, in case of evidence of infection, systemic antibiotic therapy are preferable. Empirical use of a broad-spectrum antibiotic has been shown to be effective in clinically manifest infection, in the author’s opinion, even in the absence of pathogen detection.

Depending on the assessment of the amount of exudate, highly absorbent dressings are applied or, if the wound situation is too dry, additional moisture is applied to the wound area. The amount of exudate and correct exudate management can always be inferred from the old dressing and the degree of maceration in the wound margin area.

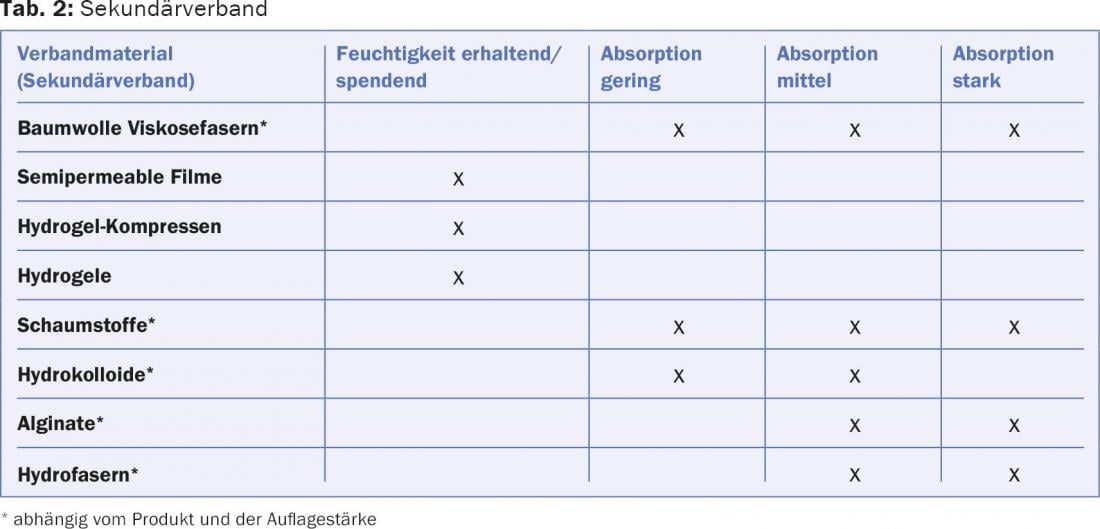

Cleaning and debridement of the wound bed is performed prior to reapplication of the wound dressing [8]. The dressing must be applied in such a way that the wound margin is optimally protected against maceration and excess wound secretion can be collected in the secondary dressing [9]. Non-adhesive and permeable wound dressings in the form of fatty gauzes, silicone dressings, etc. (so-called wound spacers) as well as semi-occlusive film dressings are suitable as primary dressings. If wound visits reveal excessively wet dressings, the frequency of dressing changes and the absorption capacity should be increased by adjusting the secondary dressing (Table 2).

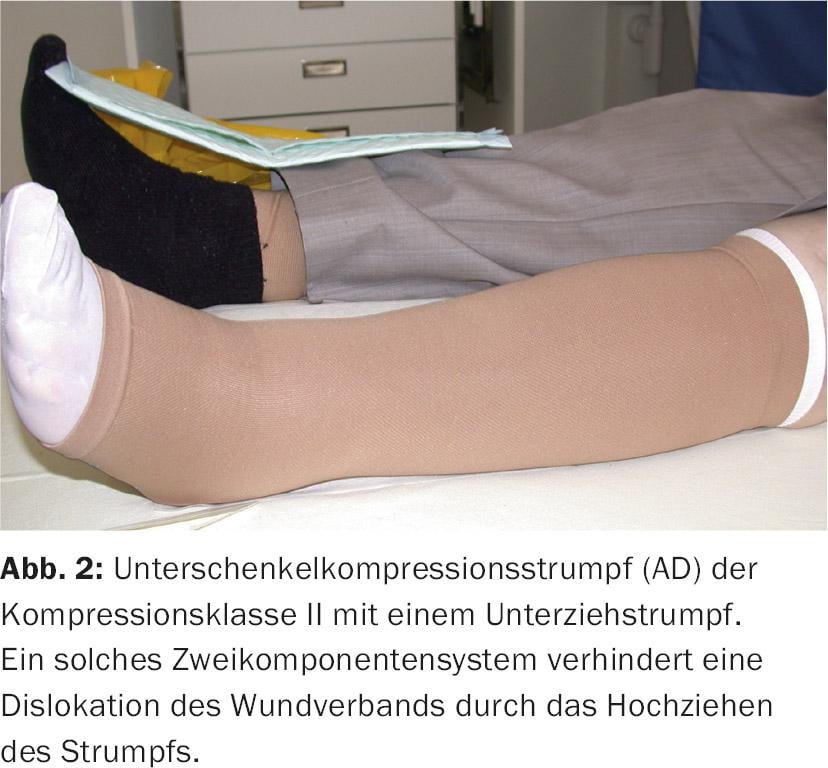

To ensure that the wound dressings remain in the intended position, a thin understocking can be used under the compression stocking (Fig. 2) . With the therapeutic goal “ulcer healing”, a lower leg stocking (AD) is usually sufficient. In practice, compression therapy with short-stretch bandages is at best preferable to stockings in connection with local wound treatment at the beginning, because the wound dressings can be better fixed and pressure/underpadding can be individually designed. Short-stretch bandages cause high working pressure and exert almost no pressure at rest, unlike the elastic material. Accordingly, it is important that patients with a short-stretch compression bandage move as much as possible in order to fully develop the compression effect. Applying a correct compression bandage requires practice and some experience (Fig. 3 and 4).

Therapy goals

The aim of compression therapy is to reduce edema. This also reduces the inflammatory reactions with the result that the wound edge and wound bed experience a significant calming already in the first few days. This calming manifests itself in a decrease in pain and a reduction in the amount of exudate. If, at the same time, it is possible to create a wound climate that complies with the principles of modern moist wound treatment by applying appropriate wound dressings, UCV usually heals. However, experience shows that even with an optimal therapy strategy, a lot of time and patience must be invested.

Reconsideration and, if necessary, adjustment of the treatment or diagnosis is always necessary if healing stagnates or the clinical situation deteriorates again. If no further progress is made despite a verified diagnosis and therapy adjustments, a surgical procedure should be considered. Surgery includes debridement and, if necessary, direct coverage of the defect with a split-thickness skin graft. We then speak of extensive surgical debridement, ulcer shaving or ulcer excision.

If the clinical situation allows and the general condition of the patient permits a major procedure, repair of the phlebopathologic condition is also conceivable during the same procedure or during the same hospitalization.

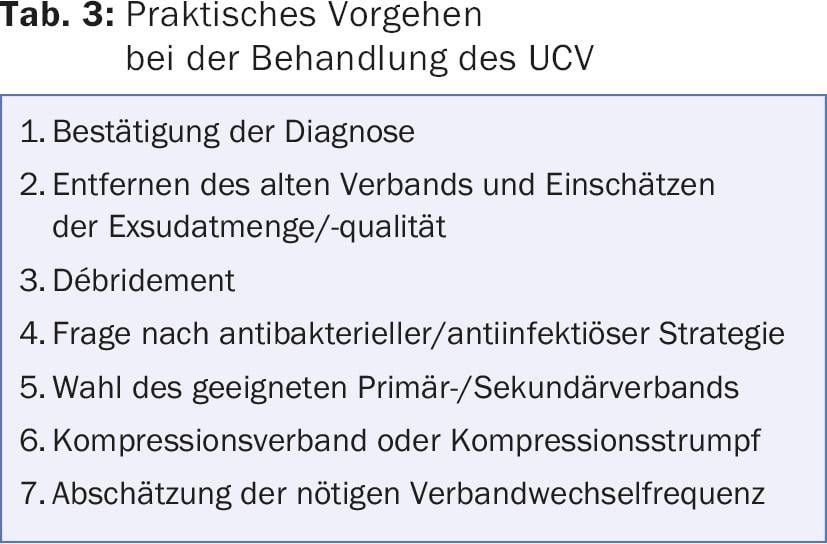

Table 3 summarizes again the practical procedure for the treatment of UCV.

Literature:

- Tatsioni A, et al: Usual care in the management of chronic wounds: A review of the recent literature. J Am Coll Surg 2007; 205: 617-624.

- Labropoulos N, et al: Secondary chronic venous disease progresses faster than primary. J Vasc Surg 2009; 49: 704-710.

- Eberhardt RT, Raffetto JD: Chronic venous insufficiency. Circulation 2005; 111: 2398-2409.

- Raffetto JD: Inflammation in chronic venous ulcers. Phlebology 2013; 28(Suppl 1): 61-67.

- Rautio T, et al: Accuracy of hand-held Doppler in planning the operation for primary varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2002; 24: 450-455.

- Haenen JH, et al: Venous duplex scanning of the leg: range, variability and reproducibility. Clin Sci 1999; 96: 271-277.

- Rhoads DD, et al: Comparison of culture and molecular identification of bacteria in chronic wounds. Int J Mol Sci 2012; 13: 2535-2550.

- Williams D, et al: Effect of sharp debridement using curette on recalcitrant nonhealing venous leg ulcers: A concurrently controlled, prospective cohort study. Wound Repair Regen 2005; 13: 131-137.

- Trengove NJ, et al: Analysis of the acute and chronic wound environments: The role of proteases and their inhibitors. Wound Rep Regen 1999; 7: 442-452.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2015; 25(5): 6-10