Prostate cancers are very common in older men. The clinical presentation varies widely. In principle, older men can also benefit from treatments.

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common malignancy in men and the second leading cause of cancer death, with both incidence and prevalence of the disease increasing with age [1]. Due to population demographics with increasing longevity, more and more men are facing the diagnosis and associated complications. Although cancer diagnoses are usually associated with mortality resp. mortality (defined as the number of deaths in relation to the total population) is mentioned as one of the most relevant parameters, it must not be forgotten, especially in the case of PCa, that significantly more men suffer from the disease than ultimately die from it [2]. This is described by the term morbidity. The leading problems here are lower and upper urinary tract outflow obstruction, hematuria, bone pain to pathologic fractures or spinal cord infiltration, and the side effects of specific treatments, all of which can have a significant impact on the quality of life of affected men.

It is precisely the loss of quality of life that is increasingly gaining weight in older men compared to the loss of potential years of life. Thus, specific treatment algorithms should be established for older men. Older men may also benefit from active treatments, but careful patient selection is extremely important to avoid overtreatment as well as undertreatment [3].

The older man

The tough questions in practice are:

- At what point is a patient old?

- What factors make a patient frail?

- Is a patient who appears fit at first glance really fit?

- Which older patient qualifies for treatment and, just as importantly, who just no longer qualifies?

Clinical experience shows that gut feelings can often be very deceiving, and unfortunately no simple triage tools exist to assign patients to the most appropriate treatment pathways. Although chronological age alone is often not a sufficient factor to define the population of older men, an age ≥75 years primarily once must and can be cited as a threshold. However, it must be taken into account that the population of elderly patients is much more heterogeneous than a younger collective.

This heterogeneity must be broken down according to objectifiable criteria, which can be done with a multidimensional geriatric assessment. This includes assessment of functionality and mobility, psyche and cognition, comorbidity, and also social and nutritional status [3]. Good and valid instruments exist for this purpose, to be able to identify primarily unrecognized deficits [4,5] and to classify the population of older men into different performance levels (fit, limited, frail) [3]. However, such an assessment would require a considerable amount of time and personnel and would go far beyond the scope of a normal consultation. In particular, however, the interpretation of the findings and the potential implementation of measures should be carried out by the relevant experts, the colleagues in geriatrics.

Thus, in individual cases, older, very fit men with a life expectancy of more than ten years may benefit from active treatments to a similar extent as a younger collective; on the other hand, frail men at the other end of the power spectrum are unlikely to benefit from more aggressive treatments because the side effects usually exceed the potential benefit. The Society of Geriatric Oncology Prostate Cancer Working Group has recently published the relevant recommendations in this regard [6].

Prostate Cancer

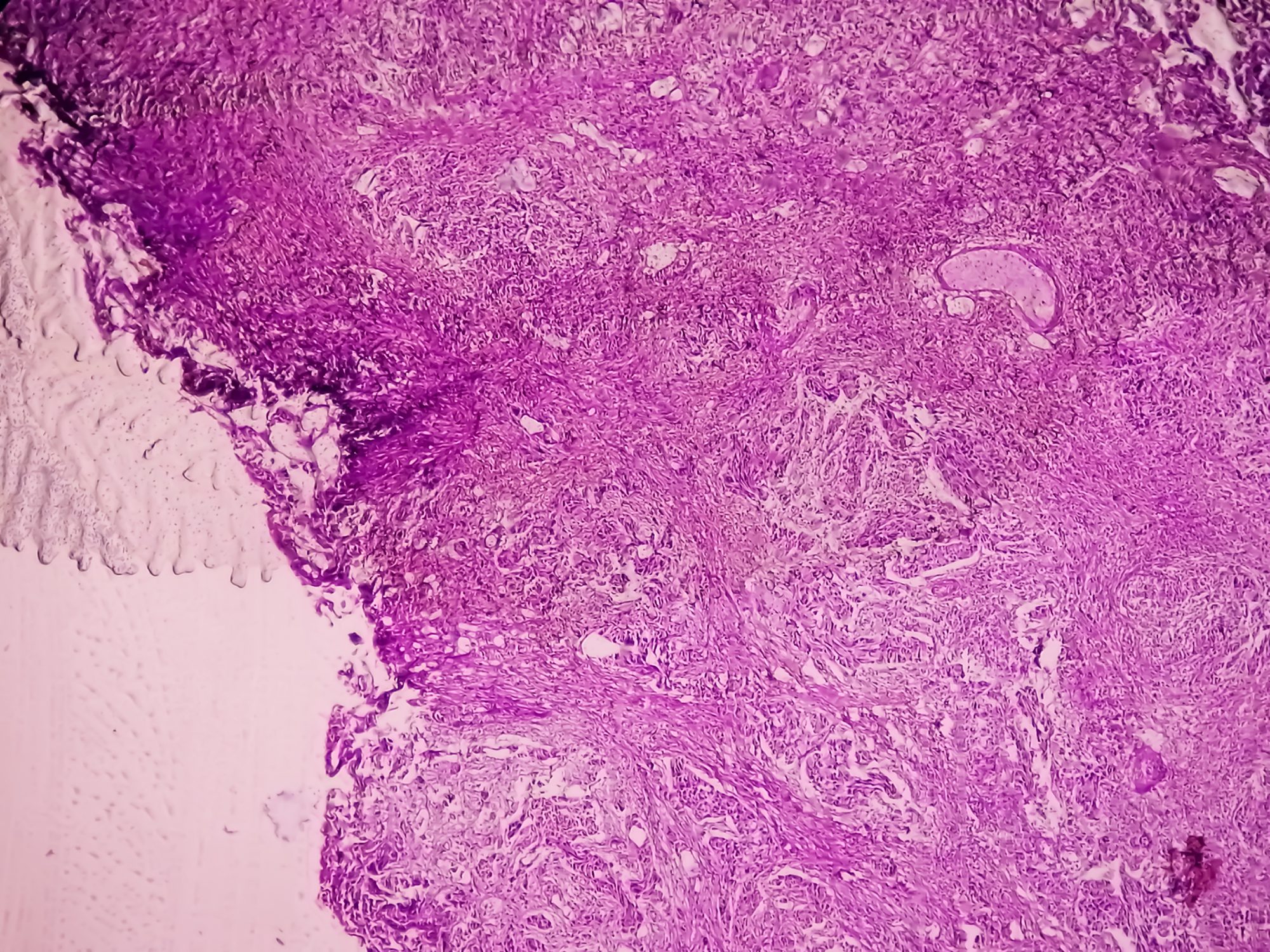

The assessment of the aggressiveness of a PCa can be made on the basis of various parameters. For this purpose, the method described by D’Amico et al. [7] developed risk stratification can be used. A distinction is made between low-risk (PSA <10 ng/ml, Gleason score ≤6, and clinical stage T1-T2a), intermediate-risk (Gleason score ≥7 and/or PSA 10-20 ng/ml and/or clinical stage T2b-T2c), and high-risk groups (Gleason score ≥8 and/or PSA ≥20 ng/ml and/or clinical stage ≥T3a). Men in the high-risk group are significantly more likely to die from their PCa compared with men in the low- and intermediate-risk groups [8]. In the well-known study by Bill-Alexson et al. [9], which randomized radical prostatectomy against a watchful-waiting strategy, demonstrated a survival benefit of radical prostatectomy only in patients <65 years. Although the study did not include an age-specific subgroup analysis, a significant reduction of metastases or cancer was also observed in the collective of elderly patients. of the need for androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and thus morbidity in actively treated individuals are shown.

Practical procedure in everyday clinical practice

Asymptomatic older men without a PCa diagnosis should not be screened for the disease as there is a very high risk of overdiagnosis due to the very high prevalence of insignificant tumors. Figures on prevalence vary widely, but according to an autopsy study in the USA, it was an impressive 83% in men aged 71-80 years [10].

If, on the other hand, symptoms are present, such as urinary retention problems, hematuria, skeletal pain, or deterioration of the general condition that cannot be explained in any other way, PCa should definitely be considered as a possible cause and the disease should then be actively sought, starting with PSA testing (prostate-specific antigen), DRE (digital rectal examination), and, if the suspicion is confirmed, prostate biopsy and the corresponding imaging for staging.

Localized prostate carcinoma: In the case of localized prostate carcinoma, the indication for local treatment with curative intent must be given with the greatest caution. Generally, only patients in the top-performing group with a life expectancy of >10 years and in the presence of more aggressive PCa (typically with Gleason score ≥8) can benefit from this. In all other cases, especially low- to intermediate-aggressive PCa, a symptom-based approach should be taken. However, the dynamics of the disease should be monitored in all cases by means of PSA monitoring in order to detect the transition to metastatic disease at an early stage and then to be able to intervene palliatively at the appropriate time. The goal here should be to prevent or reduce the complications of the disease. delaying them.

Metastatic disease: In the case of metastatic disease, all elderly patients, from frail to fit, can actually benefit from palliative treatment. However, pure PSA manipulation should be avoided. The first-line treatment is still ADT [6]; it can be performed medicinally, e.g. by LHRH analogues, or surgically by subcapsular orchiectomy. It must be remembered that ADT is associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis and metabolic syndrome, as well as cardiovascular events, especially in the elderly patient [11]. Consequently, osteoprotection via supplementation of calcium and vitamin D3 and, if necessary, denosumab should always be performed. Recently, it has been shown that early use of docetaxel during the hormone-sensitive phase of the disease provides a significant survival benefit [12] and can benefit older patients as well as younger ones. This should definitely be considered in the elderly but otherwise fit patient, especially in the case of a high tumor burden.

Castration-refractory PCa: In the case of castration-refractory PCa, various treatment options are also available to older patients (chemotherapy or extended hormone manipulation, in the case of exclusive bone metastasis also Alpharadin [Radium 223]). Several studies have shown that older men may also benefit [13–17]. However, and in particular, the aggressiveness of the treatment must also be adapted to the overall situation. In addition, a policy discussion should be held with the patient and family members at this time at the latest to discuss the further, medically reasonable treatment options and the effects that can realistically be expected. It should be made very clear that a further gain in lifetime means precisely an increasing experience of morbidity. Explaining the concept of symptom-oriented palliative treatment and also initiating it at the right time is central.

Summary

The prevalence of PCa in older men is extremely high, but the clinical presentation of the disease is very heterogeneous depending on the biological aggressiveness of PCa – from asymptomatic and often unrecognized to aggressive and lethal. The high morbidity of the disease is particularly noticeable in the collective of older men and often has a strong impact on the quality of life of those affected. Older patients can also benefit from active treatments, but the aggressiveness of the treatment must be adapted to the overall situation. Due to the heterogeneity of this population, the risk for both overtreatment and undertreatment is high. A geriatric-urological assessment is of great help here. This allows patients to be assessed beyond the clinical gut feeling and also according to objectifiable criteria and to be divided into performance groups. Treatment should take into account this range of services as well as the aggressiveness and stage of the disease in order to define a tailored treatment for each patient. Open discussion with the patient and the relatives is also a very central element here, especially if treatments that are medically possible but promise little benefit in the overall context are deliberately avoided.

Take-Home Messages

- The prevalence of prostate cancer in the older male population is extremely high.

- The clinical presentation is highly variable – just as the population of older men is heterogeneous.

- In principle, older men can also benefit from treatments.

- However, treatment aggressiveness must be adjusted to the overall situation to avoid overuse as well as underuse.

- A geriatric-urological assessment is of great help in finding a tailored treatment strategy for each patient in accordance with his or her life expectancy and capacity.

Literature:

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2013; 63: 11-30.

- Popiolek M, et al: Natural history of early, localized prostate cancer: a final report from three decades of follow-up. Eur Urol 2013; 63: 428-435.

- Fung C, Dale W, Mohile SG: Prostate cancer in the elderly patient. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 2523-2530.

- Hurria A, et al: Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: a feasibility study. Cancer 2005; 104: 1998-2005.

- Mohile S, Dale W, Hurria A: Geriatric oncology research to improve clinical care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2012; 9: 571-578.

- Droz JP, et al: Management of prostate cancer in older men: recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. BJU Int 2010; 106: 462-469.

- D’Amico AV, et al: Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 1998; 280: 969-974.

- D’Amico AV, et al: Cancer-specific mortality after surgery or radiation for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer managed during the prostate-specific antigen era. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 2163-2172.

- Bill-Axelson A, et al: Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 932-942.

- Haas GP, et al: The worldwide epidemiology of prostate cancer: perspectives from autopsy studies. Can J Urol 2008; 15: 3866-3871.

- Mohile SG, et al: Management of complications of androgen deprivation therapy in the older man. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2009; 70: 235-255.

- Sweeney C, et al: Impact on overall survival (OS) with chemohormonal therapy versus hormonal therapy for hormone-sensitive newly metastatic prostate cancer (mPrCa): An ECOG-led phase III randomized trial (abstract LBA2). American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting 2014.

- de Bono JS, et al: Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1995-2005.

- de Bono JS, et al: Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 1147-1154.

- Ryan CJ, et al: Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 138-148.

- Scher HI, et al: Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1187-1197.

- Tannock IF, et al: Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1502-1512.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(2): 9-12.