The spectrum of systemic treatment options for atopic dermatitis is currently in flux. In recent years, the interleukin (IL)-13 pathway has been shown to play an essential role in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. While the biologic dupilumab inhibits IL-4/IL-13 signaling and is already well established in practice, tralokinumab and lebrikizumab specifically address IL-13. Study data to date are very promising.

Based on advances in deciphering the immunopathological basis of atopic dermatitis, treatment concepts have been developed that specifically target type 2 immune mechanisms [1]. Innovative therapies in the form of specific monoclonal antibodies and so-called “small molecules” have ushered in a new era. The corresponding anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agents can be used in patients affected by moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and combine highly effective treatment effects with an advantageous safety profile, whereby in the sense of personalized medicine the various therapy options are to be tailored to the respective patient characteristics. This is a significant advance in the treatment options for this distressing skin disease, as conventional systemic therapy options are very limited in terms of both duration of use and benefit-risk profile, and topical therapy alone is usually insufficient.

Interleukin (IL)-13 signaling pathway as a therapeutic target.

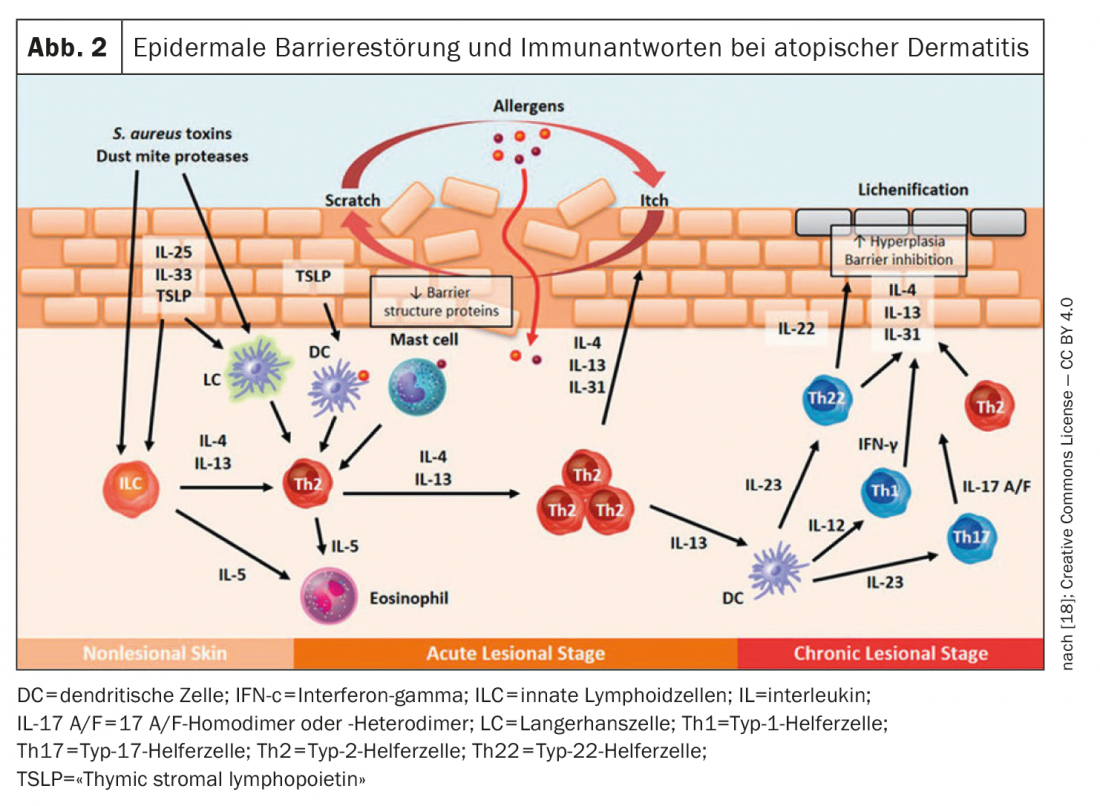

The monoclonal antibody dupilumab – the first biologic approved for atopic dermatitis – binds to the IL-4 receptor (IL-4Rα), preventing both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling [1]. Recent studies identified IL-13 as the most abundant type 2 cytokine in lesional skin in atopic dermatitis and showed that the expression level of

IL-13 in skin lesions correlates with disease severity [2–6]. Overexpression of IL-13 in atopic dermatitis skin is thought to contribute to the vicious cycle of inflammation, skin barrier disruption, and microbiome dysbiosis [2,3]. Tralokinumab, also a monoclonal antibody, specifically neutralizes IL-13 by binding to this cytokine, preventing its interaction with the IL-13Rα1 receptor [1]. This is the basis for the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties of tralokinumab. A biologic also directed against IL-13 is lebrikizumab. This IgG4 monoclonal antibody binds to an IL-13 epitope that prevents the IL-13/IL-13Rα1 complex from forming a heterodimer with IL-4Rα [2].

Tralokinumab: successful in phase III study as monotherapy and with TCS

The efficacy and safety of 52-week tralokinumab therapy in atopic dermatitis was evaluated in two multinational phase III RCTs, ECZTRA 1 (n=802) and ECZTRA 2 (n=794) [7]. In both studies, tralokinumab 300 mg every two weeks (q2w) was significantly superior to placebo in terms of improvements in the primary endpoints IGA 0/1 and EASI-75 at 16 weeks. Furthermore, significant improvements were manifested in various secondary endpoints such as pruritus, DLQI, Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD), as well as eczema-related sleep disturbances under tralokinumab [7].

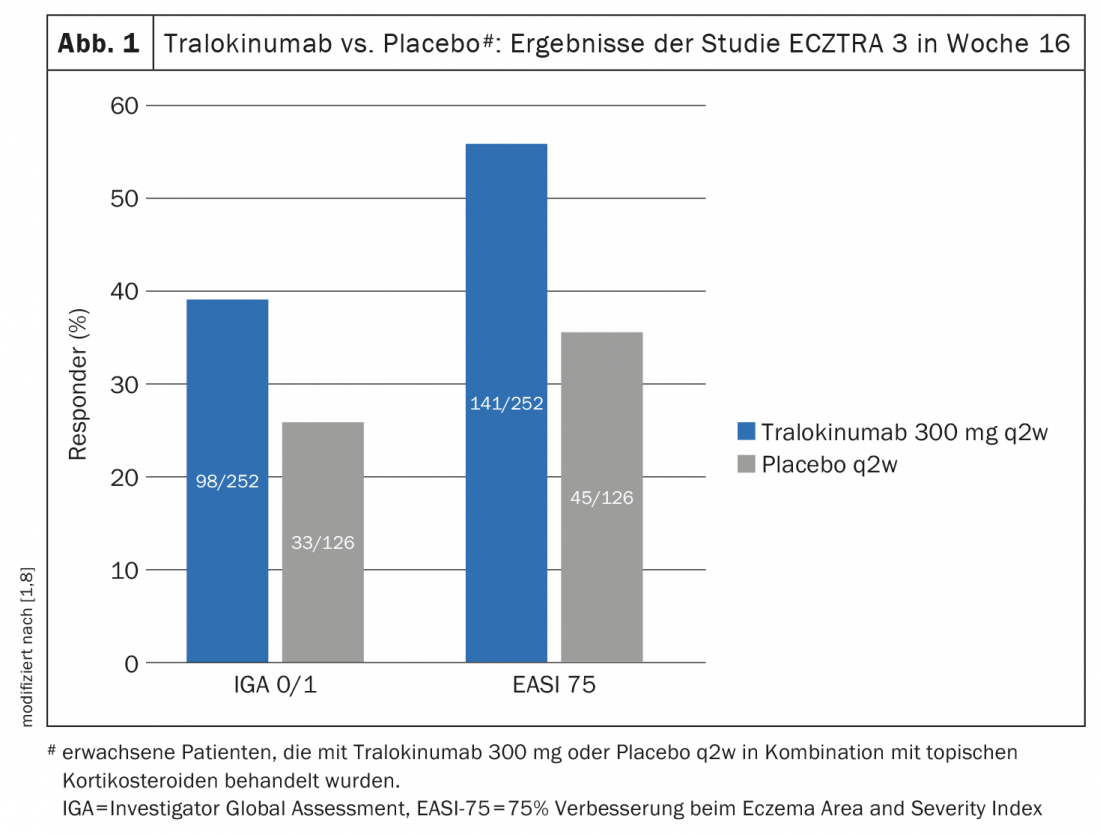

Another randomized-controlled phase III study – ECZTRA 3 – evaluated the efficacy and safety of tralokinumab 300 mg q2w in combination with a topical corticosteroid (TCS) in 380 patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis [8]. On-demand therapy with locally applied cortisone was mometasone furoate 0.1% cream (class III steroid), applicable once daily to active lesions. At week 16 of the ECZTRA 3 trial, significantly more in the tralokinumab arm achieved EASI-75 and IGA 0/1, 56.0% and 38.9%, respectively, compared to placebo, where the corresponding values were 35.7% and 26.2%, respectively (p<0.001 and p=0.015, respectively) (Fig. 1) [8]. The tralokinumab arm also proved superior in terms of EASI-90 (32.9 vs. 21.4%; p=0.022) and EASI-50 (79.4 vs. 57.9%; p<0.001). The evaluations also showed that in weeks 15-16, patients treated with tralokinumab used approximately 50% less topical steroids than the placebo group (p=0.002). Those who met the primary endpoint at week 16 were again randomized 1:1 to continue tralokinumab q2w treatment or to reduce dosing to q4w. Approximately 90% of patients were able to maintain response at week 16 through week 32 with both dosing regimens [9].

In particular, the ECZTRA 3 study compares well with everyday practice in atopic dermatitis: if TCS alone are not effective, systemic therapy is initiated. To avoid recurrence, both treatments are ideally continued in parallel [1].

Lebrikizumab: Phase II dose-finding study completed

Phase IIb studies of lebrikizumab showed dose-dependent efficacy in adults without a significant increase in the relative incidence of conjunctivitis [11]. A total of 280 patients (mean age 39.3 years, 59.3% female) were randomly assigned to one of the following study arms: 125 mg every 4 weeks (n=73), 250 mg every 4 weeks (n=80), or 250 mg every 2 weeks (n=75) or placebo. At week 16, lebrikizumab treatment showed a dose-dependent statistically significant improvement in mean percentage changes in EASI “least squares” compared with placebo. The differences from placebo manifested as early as week 4 and continued to accentuate through week 16. In addition, significantly more patients achieved an IGA 0/1 response and EASI50, EASI75, and EASI90 at week 16 at the 250 mg lebrikizumab dose compared with placebo.

Overall, the results of clinical trials to date suggest that lebrikizumab is another effective and well-tolerated treatment option for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. The efficacy and safety of this biologic for maintenance therapy and as a long-term treatment will be evaluated in Phase III trials starting in 2019 [12,13]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently granted fast-track status to this monoclonal antibody [10].

Literature:

- Wollenberg A, Weidinger S, Worm M, Bieber T: J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2021; 19(10): 1435-1442.

- Bieber T: Allergy 2019; 75: 54-62.

- Tubau C, Puig L: Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2021; 17: 15-25.

- Tsoi LC, et al: J Invest Dermatol 2019; 139: 1480-1489.

- Szegedi K, et al: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29: 2136-2144.

- Marbach-Breitrück E, et al: Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2019; 32: 192-200.

- Wollenberg A, et al: Br J Dermatol 2021; 184: 437-449.

- Silverberg JI, et al: Br J Dermatol 2021; 184: 450-463.

- Wohlrab J, et al: Dermatologist 2021; 72(4): 321-327.

- Tuttle KL, Forman J, Beck LA: Int J Womens Dermatol 2021; 7(5Part A): 606-614.

- Guttman-Yassky E, et al: JAMA dermatology 2020; 156(4): 411-420.

- ClinicalTrials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04146363, (last accessed Jan. 24, 2022).

- ClinicalTrials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04178967, (last accessed Jan. 24, 2022).

- Wei W, et al: J Dermatol 2018; 45: 150-157.

- Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S: Lancet 2020; 396: 345-360.

- Wollenberg A, et al: J Eur Acad Derm Venereol 2020; 34: 2717-2744.

- Adtralza®, EMA approval June 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/html/h1554.htm, (last accessed Jan. 24, 2022).

- Cork MJ, Danby SG, Ogg GS: J Dermatolog Treat 2020; 31(8): 801-809, www.researchgate.net/publication/336708334_Atopic_dermatitis_epidemiology_and_unmet_need_in_the_United_Kingdom

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2022; 32(1): 26-28