Case report: The father presents with Sebastian, who is three and a half years old, because he has had a red pimple under his left eye for ten months now. This appeared one day, first increased a little, but has now remained unchanged since then. The pediatrician administered treatment with an antibiotic once over two weeks. However, this did not bring any improvement. Sebastian is otherwise healthy, has never had any medical problems except for eye infections (“sty”) twice.

Clinical picture: There is an erythematous, rather soft, slightly fluctuating nodule in the left infraorbital region (Fig. 1) . No lymphadenopathies are detectable.

Quiz

Based on this information, which is the most likely diagnosis?

A pilomatrixom

B Cutaneous leishmaniasis

C Atypical mycobacteriosis

D Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG).

E nevus Spitz

Diagnosis and discussion: Based on the clinical picture and the information, basically all differential diagnoses are possible with the exception of Spitz nevus. The latter typically presents as a dome-shaped, reddish papule without crusts, erosions, or fluctuations. The consistency, described as rather soft, also makes the pilomatrixome seem unlikely.

In this asymmetric presentation, exogenous causes such as infections are certainly to be considered in the first place, whereby in addition to a banal abscess, rarer germs such as leishmaniasis (travel history!) or atypical mycobacteriosis are also possible.

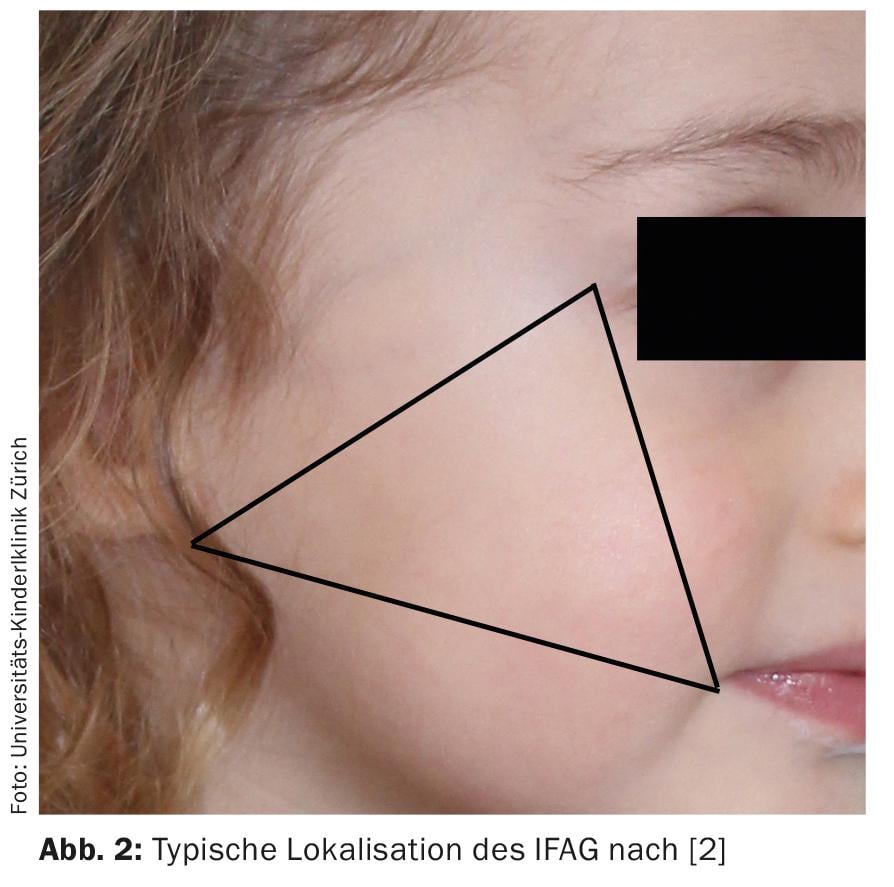

However, this history and especially the mentioned recurrent eyelid rim inflammations are also quite typical for the idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG) present in the case (answer D). This is a recently described entity occurring only in childhood [1]. Although we regularly encounter this clinical picture in our consultations, only a few publications have been devoted to the topic since then. However, a larger series from France has since better characterized the IFAG [2]. Thus, it typically occurs in the majority of preschool-aged boys, mostly as a solitary lesion (mean age 3.8 years), and is almost invariably found on the convex areas of the cheek in a triangle connecting the lateral corner of the eye, the earlobe, and the corner of the mouth. (Fig. 2). The course is always benign and spontaneous healing usually occurs after 6-18 months, often without significant scarring [2].

The etiology has not yet been determined with certainty. Microbiological studies have never been able to define a consistent infectious agent as the causative agent, and even in our experience, corresponding swabs usually remain sterile.

Recently, case reports have been accumulating that IFAG is a manifestation of granulomatous infantile rosacea [3–5]. Rosacea in childhood is often underdiagnosed in our experience, but is basically characterized by the same features as in adults (flushing, persistent erythema with telangiectasias, papulopustules, and ocular involvement, although ophthalmorosazea seems to be more common than in adults) [6,7]. Between 40-100% of children with IFAG meet the diagnostic criteria for rosacea, with eyelid involvement in the form of recurrent chalazion being the most common manifestation [3,4]. Since cases of corneal ulceration have been reported in childhood rosacea [7], ophthalmologic site assessment is useful at least when there is history or clinical evidence of ocular manifestations. Although ocular manifestations often present before the onset of IFAG, dermatologists play an important role here, as ophthalmorosazea is particularly well known in the dermatologic literature and therefore not very familiar to many ophthalmologists.

In the case of suspected IFAG with typical findings and history, we do not believe that further diagnostic workup is indicated. However, in case of atypical findings, indications of an infectious genesis or recent stay in an endemic area for leishmaniasis, appropriate pathogen clarifications and a biopsy are required.

The therapy of IFAG depends on the extent of the findings. Treatment is not absolutely necessary for small lesions, but topical metronidazole may be used. In the case of more extensive findings, children >8 years of age can be treated analogously to rosacea with doxycycline and younger children with erythromycin or metronidazole systemically for several weeks [8]. Systemic therapy is also usually indicated in cases of ocular involvement [7].

Knowledge of this clinical picture, regularly observed in pediatric dermatology, allows uncomplicated management of these patients in many cases without extensive and often unnecessary investigations.

Literature:

- Roul S, et al: Idiopathic aseptic facial granuloma (pyodermite froide du visage): a pediatric entity? Arch Dermatol 2001; 137: 1253-1255.

- Boralevi F, et al: Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma: a multicentre prospective study of 30 cases. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156: 705-708.

- Prey S, et al: IFAG and childhood rosacea: a possible link? Pediatr Dermatol 2013; 30: 429-432.

- Neri I, et al: Should idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma be considered granulomatous rosacea? Report of three pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol 2013; 30: 109-111.

- Baroni A, et al: Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma in a child: a possible expression of childhood rosacea. Pediatr Dermatol 2013; 30: 394-395.

- Chamaillard M, et al: Cutaneous and ocular signs of childhood rosacea. Arch Dermatol 2008; 144: 167-171.

- Donaldson KE, Karp CL, Dunbar MT: Evaluation and treatment of children with ocular rosacea. Cornea 2007; 26: 42-46.

- Leoni S, et al: [Metronidazole: alternative treatment for ocular and cutaneous rosacea in the pediatric population]. Journal francais d’ophtalmologie 2011; 34: 703-710.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2015; 25(2): 24-25