Generalized anxiety disorder usually begins between the ages of 20 and 30. It is accompanied by psychological and physical symptoms. Rapid clarification and making the correct diagnosis (especially in the broad field of differential diagnoses) are central to preventing further damage to the patient’s social and professional life. What do you need to know about this disease to avoid missing it in your practice? The following article provides an overview.

(ag) According to DSM-IV or DSM-5, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is excessive fear and worry (regarding multiple events or activities) occurring on the majority of days for at least six months. The person has difficulty controlling worry. At least three of the following six symptoms are added:

- Restlessness

- Easy fatigability

- Difficulty concentrating or emptiness in the head

- Irritability

- Muscle tension

- Sleep disorders.

Anxiety and worry (or the physical symptoms) cause clinically relevant limitation and are not limited to features of a mental disorder. There must be no organic causes. “Somatic symptoms in particular are too rarely recognized as part of GAD, even though they are often the first symptoms,” said Philipp Eich, MD, Liestal. “Because they result in numerous examinations to determine the supposed organic cause, they obscure the view of the psychological components of GAD.” This thus remains undetected and untreated. Physical symptoms associated with GAD may include:

- Sleep disorders and problems falling asleep

- Pain, muscle tension and soreness, muscle soreness.

- Tachycardia, palpitations, sweating

- Dizziness, lightheadedness

- Gastrointestinal symptoms, e.g., nausea, diarrhea, irritable bowel syndrome.

“In addition to physical symptoms, GAD naturally includes psychological symptoms such as nervousness, irritability and worry, problems concentrating or mental emptiness and, of course, anxiety. Restlessness, tension and the inability to rest are also found. Uncertainty factors are not tolerated by the patient, he has difficulty in assessing and coping with problems,” says the expert. “Although it has anxiety in its name, GAD usually does not present primarily with this symptom. Studies show that somatic disorders, pain, sleep disturbances and depression are more common as major symptoms.”

GAD in the family practice

GAD is often not recognized in the primary care physician’s office. Why is that? In addition to just over one-third of patients who are correctly diagnosed, there are about two-thirds in whom, according to studies, the primary care physician either does not recognize the mental disorder or does not associate it with GAD. “Several barriers exist that stand in the way of identifying mental disorders,” Dr. Eich said. “On the part of the patient, there is sometimes a fear of stigmatization or, when visiting the doctor, people only complain about the physical symptoms and disregard the psychological ones. On the doctor’s side, the problem may be that he is not well enough informed about the diagnostic criteria or the best questions to ask. In addition, he may be under time pressure or feel discomfort in dealing with emotional problems. Concern about reimbursement may also play into it.”

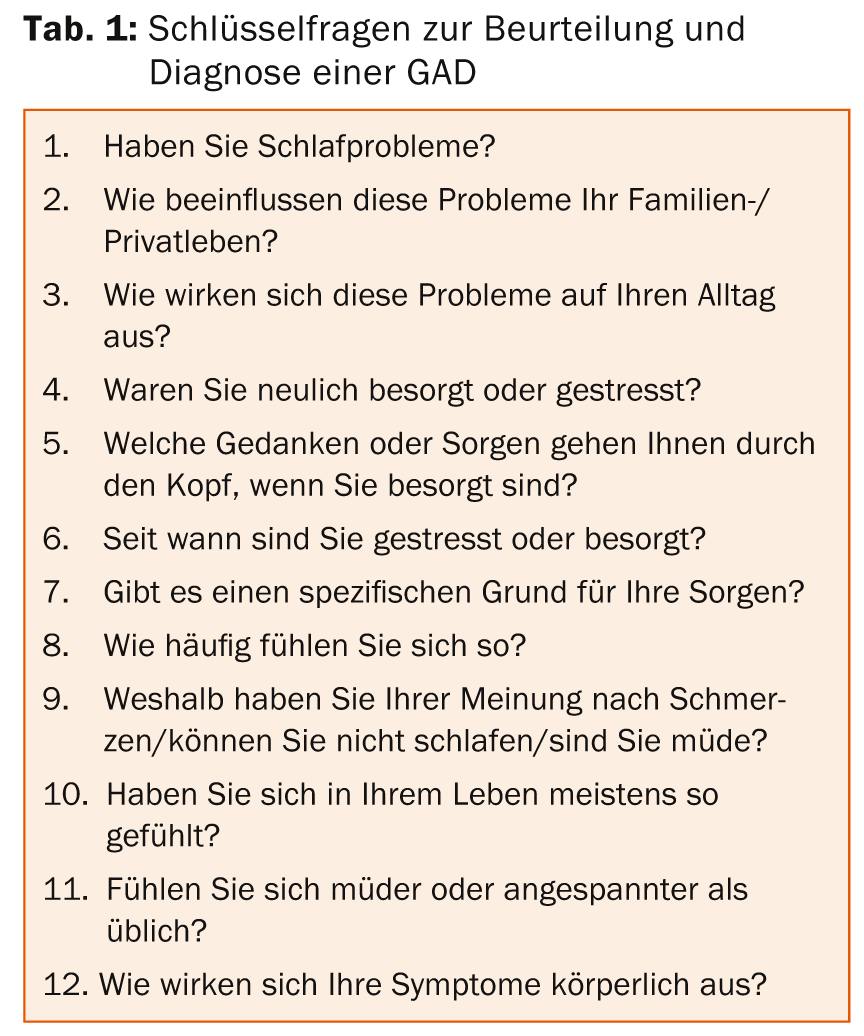

An overview of key questions in the assessment and diagnosis of GAD is provided in Table 1. There are numerous questionnaires (GAD-7 for detecting GAD; PHQ-2 for depressed mood and anhedonia; HADS for anxiety and depression) that patients complete themselves. They help the doctor identify GAD or depression. However, the current diagnostic criteria of ICD-10 or DSM-5 should be consulted for the final diagnosis.

Therapy options

Several nonpharmacologic options exist for supportive treatment of GAD. These include psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation exercises, psychotherapy and self-help (bibliotherapy). In particular, according to the speaker, the indication for psychotherapy should be made early or in a timely manner.

In any case, according to Dr. Eich, the patient’s age, tolerance, preferences and concomitant diseases should be clarified before prescribing a drug. In addition, the severity of the disease, previous response to treatments, and the potential for interaction with concomitant medications should be considered. The costs of the respective therapy also play a role, of course. “Is there a risk of intentional self-harm or accidental overdose?” Such questions must be clarified before prescribing.

The first-line medications, according to Dr. Eich, are SSRI/SNRI and pregabalin. “After that, the rule is: start low – go slow. There is a large placebo effect in these patients, they are very sensitive and usually complain of many side effects. Moreover, the SSRIs and SNRIs must be reduced gradually. Discontinuation phenomena must be taken into account, e.g., the discontinuation syndrome, which increases anxiety and shows vegetative symptoms.”

Source: Media Round Table, June 19, 2014, Zurich