Itching in the genital area is common and severely debilitating. Often the cause is a fungal infection – but by far not always. Sometimes underlying pruritus are noninfectious dermatoses, allergic reactions, drug side effects, or systemic diseases. Stephanie von Orelli, MD, Zurich, went into more detail about the different forms at the KHM Congress.

Colpitis/vulvitis is one of the most common reasons for gynecological consultation (20-25%). Affected women report a wide variety of leading symptoms, such as increased fluorine (caution: not all fluorine is pathological), unpleasant odor, itching and burning, discomfort during micturition, or dyspareunia. “Most often, the cause is a disruption of the ecosystem in the genital area,” emphasized Stephanie von Orelli, MD, of Zurich. “Vaginal douching, which seems to have come back into vogue, mechanical irritation, frequent showering and the use of alkaline soaps, as well as panty liners and menstrual bleeding, can permanently disturb the vaginal acid-base balance and thus encourage the proliferation of pathogenic germs.” The following diseases are accompanied by the leading symptoms of itching and/or fluoride:

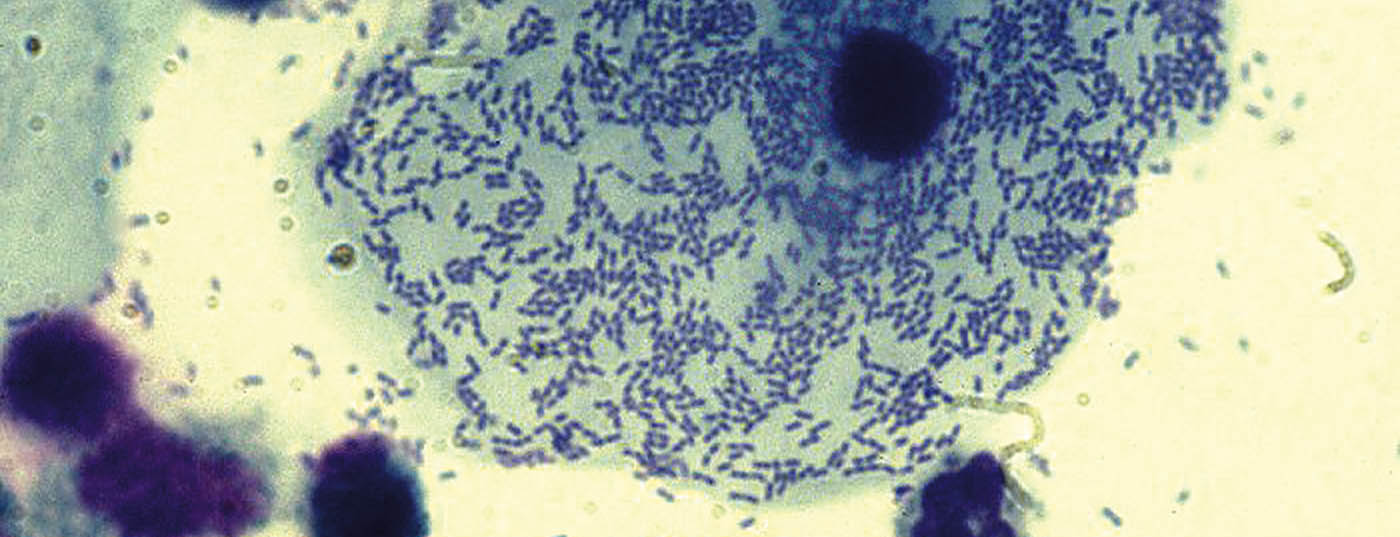

Bacterial vaginosis: Typical of bacterial vaginosis (aminocolpitis, gardnerella colpitis) is the thin, homogeneous milky fluorine that develops the typical fishy odor when potassium hydroxide (KOH) is added. In the smear, after staining with 1% methylene blue solution, so-called “clue cells” are found, vaginal epithelial cells covered by a bacterial lawn (Fig. 1) , and numerous leukocytes.

“Basically, you don’t have to treat every case of gardnerella colpitis. If the woman is not disturbed, it is not mandatory to treat,” Dr. von Orelli explained.

Treatment indications include bothersome symptoms, planned gynecologic surgery (curettage, hysterectomy), and pregnancy to prevent preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes. It is also now known that bacterial vaginosis increases the risk of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and HIV, so treatment of high-risk patients may be appropriate. First-line agent outside pregnancy is metronidazole 2× 500 mg/day p.o. for seven days or 2 g on the first and third days (less effective). “Don’t forget to tell patients that metronidazole has an antabuse effect,” Dr. von Orelli emphasized. In pregnancy and in women who cannot tolerate metronidazole, clindamycin 2× 300 mg/day p.o. is given for seven days, or at most clindamycin 2% cream topical 2 × day. Partner therapy is not necessary.

Soorkolpitis: Candida albicans is a facultative pathogen and is found in 10-30% of vaginal swabs and in 20-30% of stool specimens. The infections can be acute and relatively often chronic-recurrent. Antibiotic treatments predispose to soorkolpitis, but women taking the pill also have a slightly higher risk. In this case, a pill with a lower estrogen dose may help. “But watch out, a pill with very little estrogen can lead to atrophy, which then also causes itching. So it’s not always easy to find the right balance,” Dr. von Orelli warned.

The leading symptom is itching; the fluor is dry and crumbly. Occasionally, rhagades may also form. Thrush infection typically occurs in younger women and does not occur after menopause. Treatment is usually local with imidazole preparations (ovules, ointments), partner therapy is not necessary. In chronic recurrent infections, it may be worthwhile to do a culture, as certain strains of Candida are resistant to imidazole. Even more important in chronic recurrent thrush, however, are lifestyle changes such as avoiding intimate sprays, panty liners and recycled toilet paper (contains many substances that can lead to sensitization), possibly Gynoflor® as prophylaxis after sexual intercourse and after swimming, and a low-sugar diet for diabetics. Treatment with Diflucan® (3× 150 mg p.o. at 72-hour intervals, then 1×/week for 6 months) can be made on a trial basis.

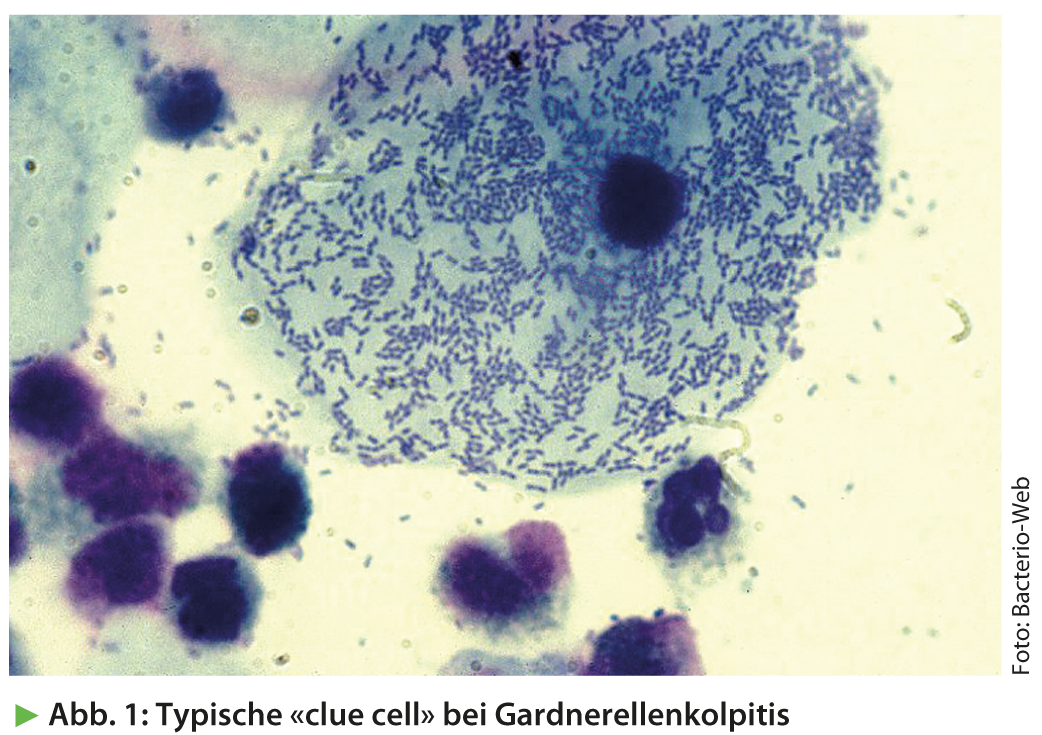

The differential diagnosis of chronic recurrent pruritus may be due to various causes other than thrush, which are summarized in Table 1 .

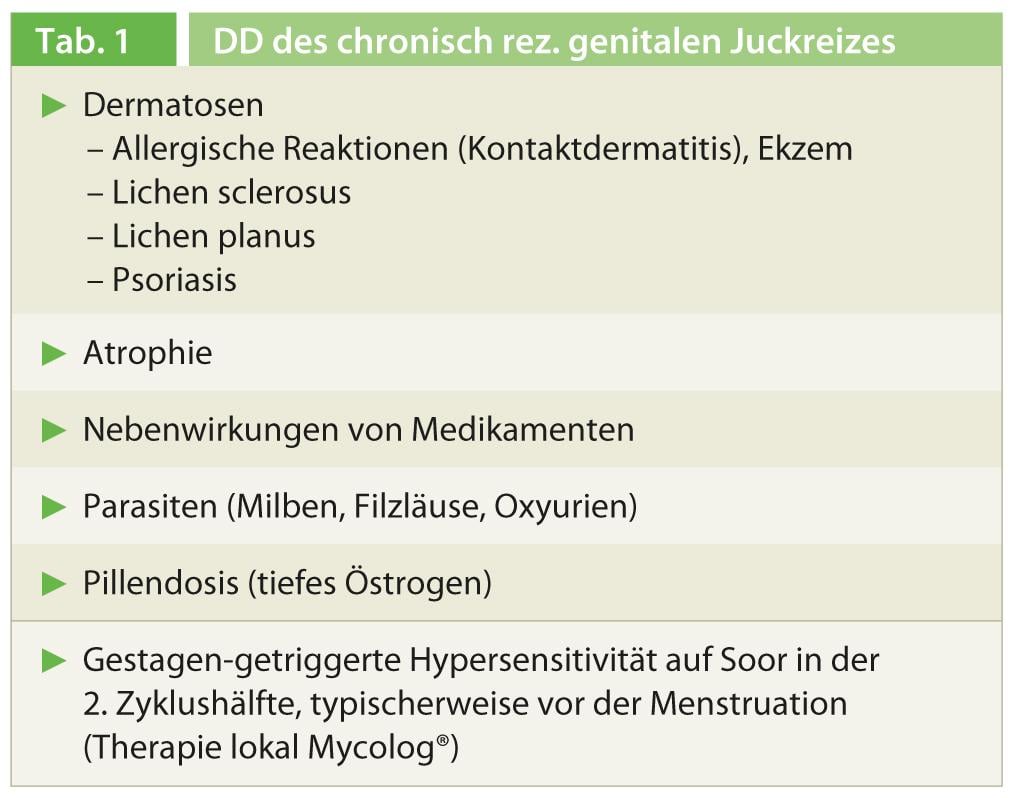

Lichen sclerosus: Lichen sclerosus can already occur in younger girls and is manifested by itching and lichenification of the external genitalia with thinned, white shimmering skin (Fig. 2). In later stages, adhesions may lead to deviation of the urinary stream. The diagnosis is made histologically. Lichen sclerosus predisposes to vulvar cancer, which is why affected women should be checked every six months. Treatment consists of repeated local steroid bursts of 2-3 weeks duration.

Lichen planus: Lichen planus is less common than lichen sclerosus and can manifest enorally and genitally. The leading symptom here is also itching. The livid, flattened plaques form typical whitish reticular structures, especially between the labia minora and majora. The diagnosis must be confirmed histologically, and treatment is with steroids. Without treatment, lichen planus erosivus (lichen ruber) develops in the further course.

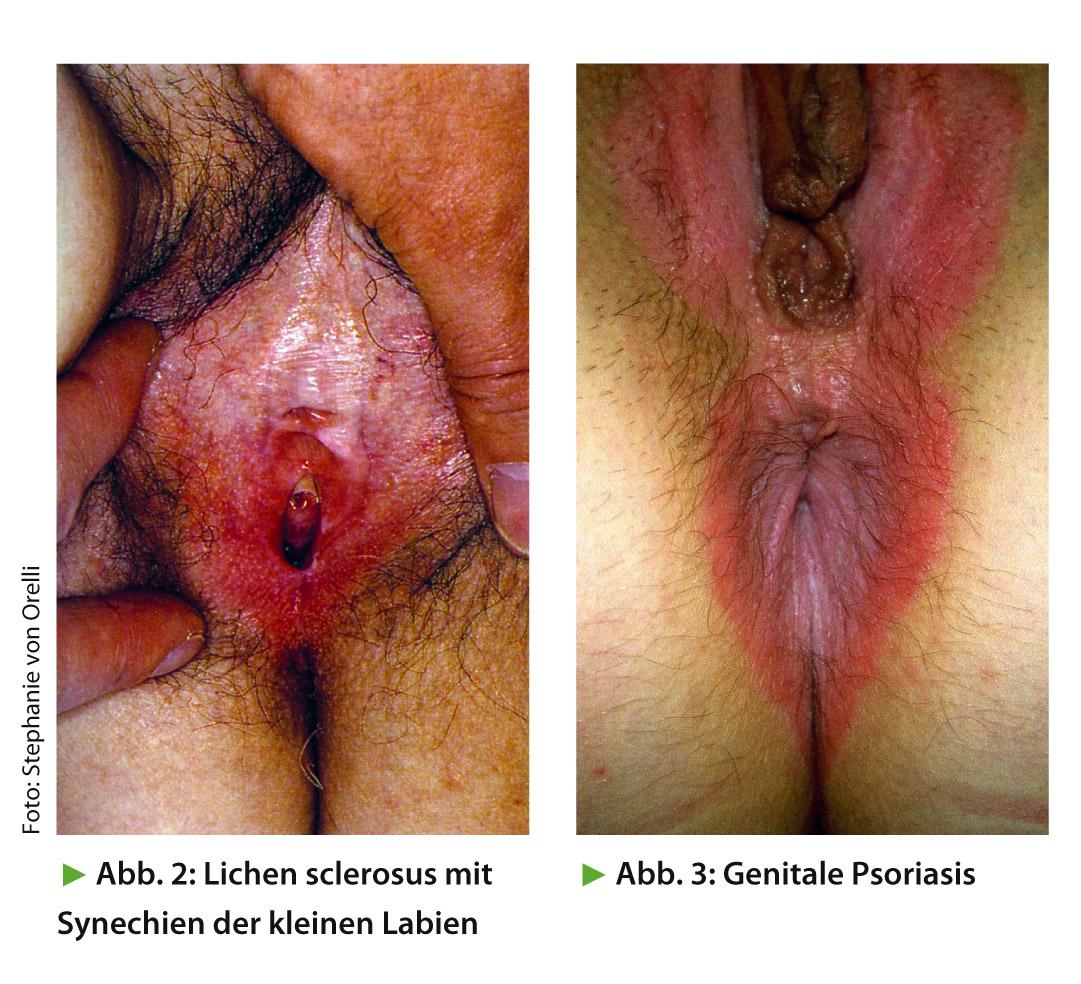

Psoriasis: Psoriasis rarely manifests itself genitally and is characterized by sharply defined redness and itching (Fig. 3). The typical erythrosquamous plaques are not found genitally. The diagnosis is made histologically. Treatment is with steroid and fat ointments.

Eczema: Eczema is wet (vesicles) in the acute stage and dry (skin thickening, scaling) in the chronic stage. Often it is a contact allergy, which is why the triggering allergens must be searched for. Treatment consists of local steroid application and avoidance of the triggering allergens.

Source: “Genital itching moist or dry: It is not always fungus!” Workshop at the 15th Continuing Education Conference of the College of Family Medicine (KHM), June 20-21, 2013, Lucerne.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2013; 8(9): 43-44