Whether it is the price to pay for the benefits of being bipedal remains to be seen, but in a sports medicine consultation, nearly 95% of patients complain of lower extremity discomfort (dysfunction, loss of function, pain, etc.). Quite a few of these complaints are localized in the lower leg (between the knee and ankle). The following is a presentation of some of these clinical expressions.

As usual in sports traumatology, a distinction must be made between acute injuries and more insidious overuse pathologies. Table 1 summar izes these different pathologies.

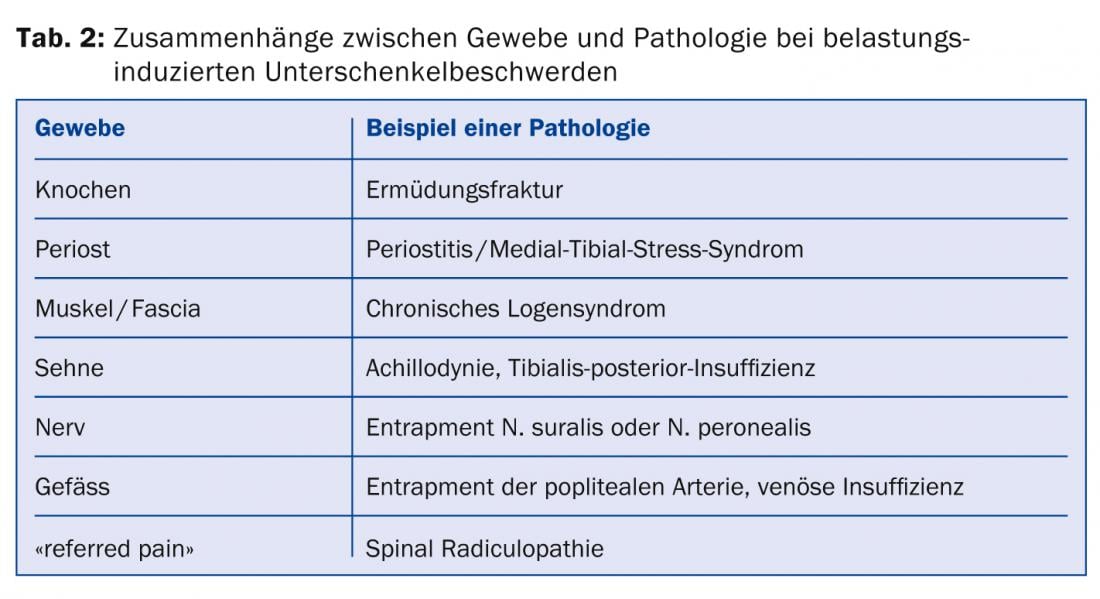

Various biological structures may be involved in overload symptoms, and Table 2 provides an overview of existing possibilities. In the following, we will briefly discuss some of these lower leg/leg complaints that occur in athletes.

Fatigue fractures

Fatigue fractures occur as a result of constantly recurring muscle action on a bone that is not normally prepared for these loads. Most of the time, the exposure is new, stronger, or different than usual for the person in question. Meanwhile, fatigue fractures sometimes develop even in well-trained athletes.

The history provides the key to the diagnosis. It is important for the physician to ask about athletic activity in the history when encountering a patient with a recent history of pain or irritation in one or both lower extremities. The classic antecedent of a fatigue fracture is the onset of pain with a new or more intense activity, which may improve with rest and worsen with continued activity.

Clinical examination of the pain area is relatively modest. Usually there is localized tenderness, occasionally there is palpable swelling over the fracture. Diagnosis should be made by conventional radiographs, scintigraphy, or MRI.

Therapy ranges from pure relief, in some cases only sports abstinence, to surgical intervention, depending on where the fracture is located. The so-called high-risk fractures, which are encountered at the patella, tibia, or medial malleolus, tend to be operated on, while low-risk fractures, such as those at the fibula, tend to be approached conservatively.

Far more important than primary treatment is the analysis and correction of etiologic factors. Interdisciplinary cooperation between trainers and sports physicians as well as the inclusion of special fields such as psychology, nutritional counseling, gynecology or biomechanics are of utmost importance. The correction of etiological factors also serves to prevent further injuries.

Medial-tibial stress syndrome or shin splints

Periosteal irritation of the tibia, also called shin splint or medial-tibial stress syndrome, is among the differential diagnostic considerations of lower leg pain. Behind this is a series of painful overuse injuries that have different causes. The most frequent localization of these pathologies is the inner tibial edge. Periosteum is found there, but muscles also originate there, e.g. the long toe flexor (M. flexor digitorum longus), the posterior tibialis muscle (M. tibialis posterior) and the soleus muscle (M. soleus). If there really is painful irritation at this inner tibial edge, the muscles originating there are often to blame. This microtraumatic lesion is often found in athletes who run or jump, usually also favored by dynamic foot disorders such as hyperpronation. In the initial stage, the pain is present only with exertion; it disappears with rest. Over time, however, the pain can become permanent, even without exertion.

Clinical examination is not very specific, with only diffuse tenderness, usually of the middle third of the medial edge of the tibia. Symptomatology may be exacerbated by passive dorsiflexion or plantar flexion of the ankle against resistance. However, these clinical signs do not allow differentiation from a stress fracture. The paraclinical balance is absolutely unremarkable. Only scintigraphy and MRI can answer this. Scintigraphy shows a diffuse increase in contrast on the posterior-medial margin of the tibia in the middle and distal thirds. The precise etiology of MTSS is unknown and many authors consider it a dynamic transition to stress fracture.

The treatment of MTSS attempts, if possible, to correct the identified causes (shoe inserts, correct footwear, muscle training of the muscles involved, etc.). Besides, substitute forms of training (aquarunning, cycling), antalgic medications and physiotherapy measures are applied.

Chronic Lodge Syndrome

Chronic lodge syndromes occur primarily during physical activity, with specific overuse of isolated muscle groups. They respond by microtraumatizing mainly the elastic elements, resulting in edema and circulation restriction that the muscle is unable to compensate for by working under anaerobic conditions. This is followed by chronic myogelosis with increased tone of the muscles and poor adaptability. By definition, the symptoms of lodge syndromes are based on increased internal pressure in individual muscle compartments.

The clinical signs appear in the form of pain. These increase in size as the load increases, until they are so severe that they force the interruption of activity in most cases. With cessation of activity, the pain slowly diminishes, but may readily persist for several days. Palpatory muscle is usually indurated and myogelotic, but these signs are relatively nonspecific. For an accurate diagnosis, the only thing that can really be done is log pressure measurement with mobile, digital pressure measurement systems. Under the guidance of a thin hollow needle, the pressure transducer is inserted into the affected muscle cell after local anesthesia and disinfection of the skin. After the probe has been placed, the resting pressure is measured and continues to be recorded continuously during the load until at least ten minutes after the load has been discontinued. Actually, only the pressure measurement under sport-typical load with subsequent progress control of the pressure drop is valuable.

Treatment of chronic lodge syndrome is almost exclusively surgical. In this case, the required fasciotomy can be performed endoscopically today.

Lower extremity nerve compression syndrome

When clarifying a pain pattern under stress in an athlete, a nerve compression syndrome (entrapment syndrome) should be considered in addition to the previously mentioned overuse syndromes. Intramuscular scarring after injury can mechanically compromise a nerve. Occasionally, iatrogenic surgical scars may also be responsible for nerve compression.

Pain is the leading symptom, very often in neuralgic form with typical distal and/or proximal radiation along the course of the nerve, which can be triggered by direct tapping or stretching (change of position or muscle contraction). Not only sensitive but also motor nerves can cause pain.

The search for muscle tears and strains and the accurate recording of the pain character have a central value in the anamnesis. Clinical examination attempts to elicit a pain known to the patient by provocation (“memory pain”). Direct tapping and stretching can imitate such pain known to the patient.

Test anesthesia, fractionated distally to proximally, may also help establish the diagnosis. Basically, nothing can be expected from the imaging diagnosis, but indirect signs can be found in the X-ray (periarticular ossifications, osteophytes, fracture with callus, etc.). Neurophysiology is predominantly helpful in the chronic situation.

Therapy is conservative in the early stages with physical therapy, neuromeningeal structural stretching, and physical therapies. In case of therapy resistance, surgical decompression of the nerve in terms of canal splitting, canal dilatationplasty, adhesiolysis, lodge splitting, neurolysis, relocation or even neurotomy may be necessary. In the lower leg, the superficial peroneal nerve should be considered; more distally, the tibial nerve is also important.

Vascular diseases

Certain leg symptoms may be caused by narrowing of the popliteal artery. They lead to claudication even in younger, athletic patients. Mostly it is the narrowing of the artery into musculo-aponeurotic structures, partly caused by abnormal developments.

The development of pain is less typical than in lodge syndrome, sometimes pain occurs with walking rather than running. This is probably due to stronger contractions of the gastrocnemius medialis (this partly explains the higher frequency of appearance in dancers and cyclists).

The diagnosis is made sonographically and treatment is surgical.

Jogger’s syndrome has been described in the literature, a thrombosis of the superficial femoral artery at the exit of the canalis adductorius (Hunter), with resulting calf pain. It is speculated that this rare but serious pathology is caused by scissor-like compression of the artery by the tendon of the vastus medialis and adductor magnus.

Summary

Leg pain is a common but under-recognized syndrome compared to other areas of the body. They can have a variety of causes. This also applies to sports. So it’s definitely worth getting to know this “Exercise-related leg” pain better.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(7): 9-10