Treatment recommendations and guidelines offer the possibility of rapid acquisition of current and practice-relevant knowledge, make decision-making more transparent for physician and patient, and provide guidance for treatment with regard to ethical, legal, and medical aspects. However, they are in no way a substitute for ongoing education or even a viable doctor-patient relationship.

In his presentation at this year’s Swiss Forum for Mood and Anxiety Disorders of the Swiss Society for Anxiety and Depression (SGAD), Zurich, Prof. Paul Hoff, MD, addressed the general aspects of guidelines in medicine and specifically in psychiatry. Guidelines are a core component of evidence-based medicine (EBM) and are currently a topic of very broad and, in part, controversial discussion throughout the medical community. In the context of EBM, evidence is the result of systematic evaluation of published results of scientific studies. “That is, EBM is a rationally reviewed and verifiable form of current scientific knowledge, not the personal opinion of an eminence,” Prof. Hoff explained. It is often forgotten that EBM is a continuous process and not a final outcome. One of the best-known databases of evidence-based information is the Cochrane Library. Here, anyone interested can find robust data material on the treatment of a specific disease.

Guideline – Guideline – Treatment recommendation?

Guideline, guideline and treatment recommendation differ in their – partly also legal – binding force and thus also in the decision-making scope of the physician who applies them. The narrowest version is the directive, which is to be understood as a regulation in the administrative field, for example, and must therefore be taken into account. Guidelines, on the other hand, are recommendations and differ in principle only in terms of language from treatment recommendations. “Although the guidelines issued by the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS) are not legally binding and do not have the force of law, they are slowly entering the realm that lawyers call soft law.” Soft law is not a law that is mandatory to consider and therefore enforceable, but soft law can cause problems if it is not considered and something happens. With the discussion about guidelines, we are therefore also entering a legal area,” Prof. Hoff pointed out.

In medicine, guidelines generally create the possibility for rapid acquisition and thus also application of current and practice-relevant knowledge. On the other hand, many colleagues fear that the individual character of the treatment process could be lost through guidelines and that the medical identity with freedom of treatment and the usually quite large scope could increasingly change negatively in the direction of regimentation and technocracy.

Guidelines in psychiatry

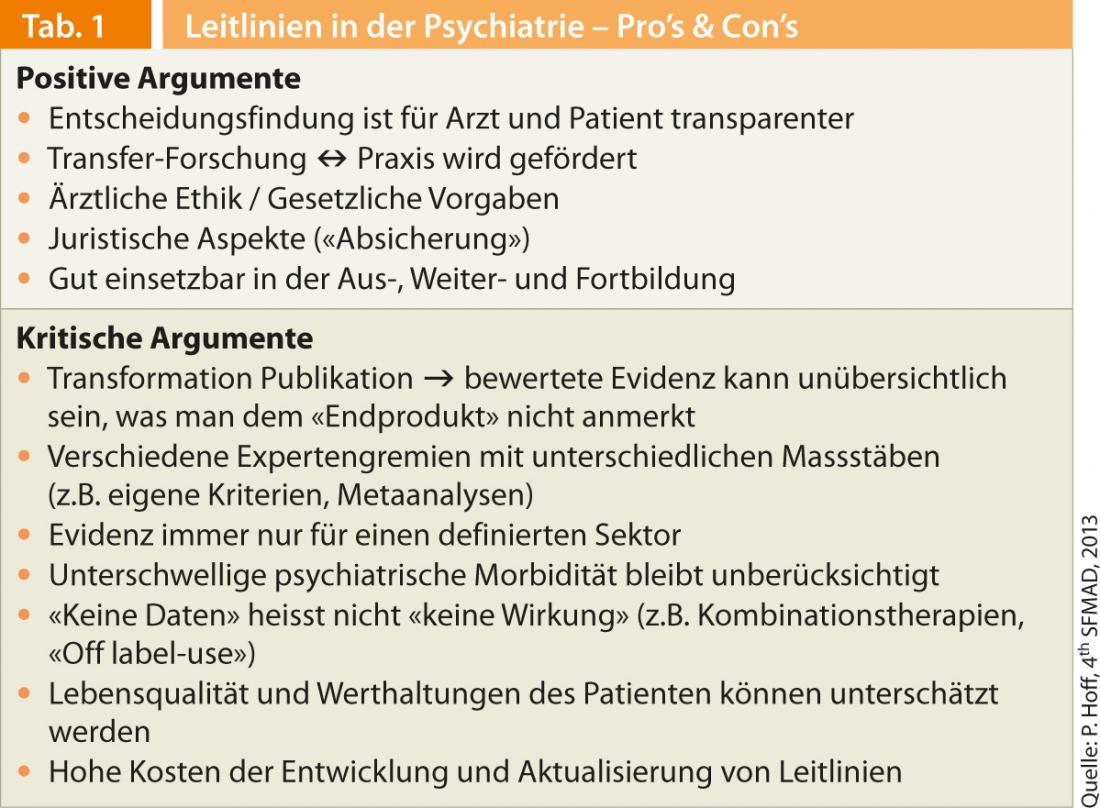

Also with regard to the use of guidelines specifically in psychiatry, the spectrum of arguments for and against is very wide (Tab. 1) . The advantages of guidelines include better transparency of decision-making for physicians and patients. Prof. Hoff gave an example: “Especially in acute psychiatry, where we often have to deal with particularly delicate situations, such as FU (fürsorgerische Unterbringung [since 1.1.13 instead of FFE; editor’s note]) of hectic, agitated psychosis patients, etc., the reference to a guideline and a consensus of experts can be very helpful when talking to the patient.” Guidelines promote the transfer of research into practice, are helpful in informing the patient and justifying treatment (ethical duty), and can additionally be a legal safeguard. Finally, guidelines are very well suited for education, training and continuing education.

On the other hand, in the context of guidelines, one must be aware that the transformation from scientific publication to evaluated evidence, i.e., to guideline, is a very complex, multifaceted, and often confusing process. Further, not only facts but also evaluated facts are taken into account. According to Prof. Hoff, various authors also point out that subthreshold psychiatric morbidity may be underestimated in operational guidelines. “In terms of whether or not a patient who doesn’t meet the criteria for a diagnosis right now but is unwell is sick and needs to be treated, experience often helps more than the guidelines and you may still need to treat the patient.”

Another important point is the fact that there are no data on many treatments, especially, for example, on multimedication, which is often used in clinical practice. “However, this does not mean that these treatments do not work. ‘No data’ does not mean ‘no effect’!”, Prof. Hoff emphasized. Guidelines and operational diagnostic manuals cannot practically take into account the individual values of the individual patient, but the latter nevertheless plays an important role in everyday clinical practice and must be taken into account. Finally, one must always be aware that meta-analyses, which serve as a basis for guidelines, have their methodological limitations: All studies can never be included, the selection criteria of the individual studies are often very different, and negative results are often not published at all and thus cannot be considered in a meta-analysis. Furthermore, study results can often only be generalized to a limited extent. It is also important to distinguish between efficacy and effectiveness. The efficacy demonstrated in the study is not necessarily identical with the effectiveness in practice and clinic.

Conclusion

- Guidelines are modifiable, highly methodological elements of the examination and treatment process. They are useful tools, but not laws, dogmas or worldviews.

- The task of the guidelines is – quite pragmatically – to reduce the probability of errors.

- Guidelines can be misunderstood, even misused. They may limit the physician’s and patient’s scope for decision-making quantitatively, but not qualitatively.

- Whether medical guidelines are experienced as a pleasure or a frustration depends largely on the self-image of the professional who uses them.

- Guidelines are useful tools, but they are no substitute for continuing education or even for a viable physician-patient relationship.

Source:4th Swiss Forum for Mood and Anxiety Disorders (SFMAD), Zurich, April 18, 2013.