Over the past decade, mindfulness-based therapy for anxiety and depression has evolved from a marginal position in the therapeutic field to a recognized, empirically based practice. In addition to its use in relapse prevention in depression, recent studies now indicate that this form of therapy may also have value in acute depressive episodes.

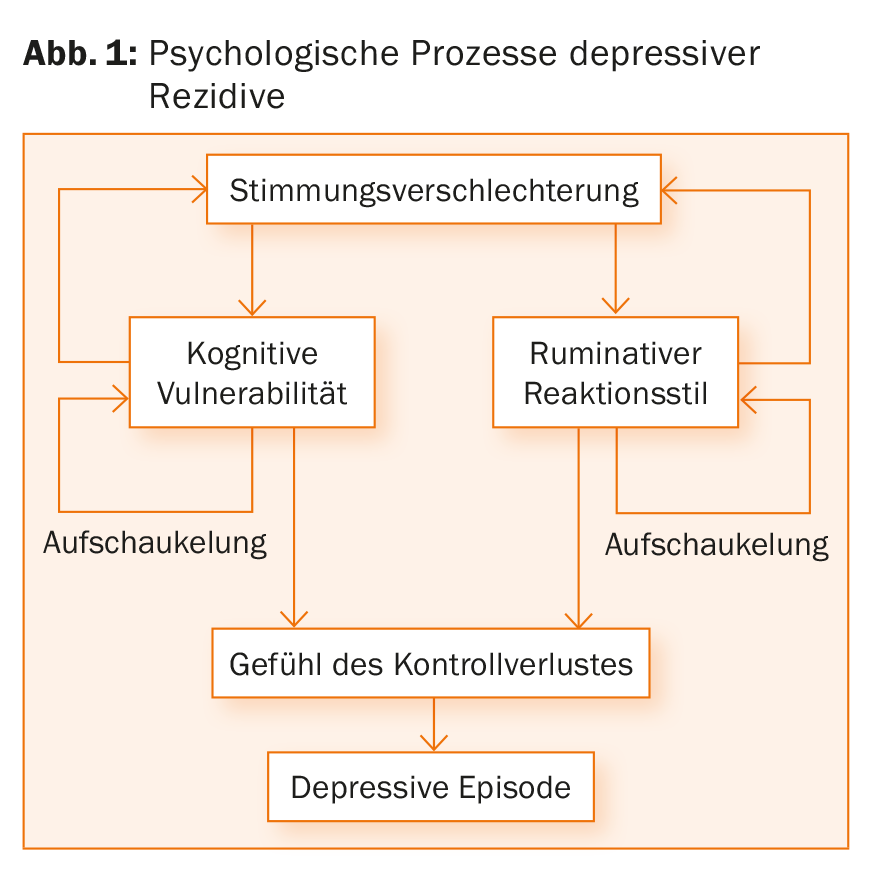

The term mindfulness training is currently on everyone’s lips. Conscious awareness forms the core concept here and is intended to contribute to stress reduction. Historically, the term “mindfulness” is primarily found in Buddhism. The secularization of mindfulness occurred in part through the American molecular biologist Jon Kabat-Zinn, who used mindfulness therapies with patients suffering from chronic pain and later developed Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) as a health-promoting lifestyle. Mindfulness therapy is now also used as part of other treatment approaches. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), for example, is used in the area of relapse prevention of recurrent depressive disorders. In doing so, it counteracts the build-up processes that typically contribute to a relapse of a depressive episode (Fig. 1). In practice, this means:

- Being in touch with the present moment and not with memories or plans for the future

- Perceive thoughts, feelings, body sensations without evaluation

- Consciously perceive even slight mood changes and automated cognition; view thoughts and feelings as mental events and reflections of reality (“decentering”).

Areas of application of mindfulness therapy

In practice, MBCT is used for patients with status post multiple depressive episodes, e.g. in the form of a group therapy lasting several weeks, in which, in addition to the joint performance of mindfulness exercises and the application of cognitive-behavioral therapy elements, the recurrent application of what is practiced in everyday life can make a decisive contribution to success.

The effectiveness of this form of therapy has been investigated in several studies. Kuyken et al. were able to show in the PREVENT study that drug maintenance therapy over two years was equivalent to Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) in the prophylaxis of recurrences of depressive episodes [1]. Similarly, no significant difference was found with respect to cost-effectiveness. MBCT proved to be particularly effective with those patients who had suffered childhood trauma.

It would be interesting to know whether, in addition to its use in prevention, mindfulness therapy is equally suitable for the treatment of an acute depressive episode or anxiety episode. This question was addressed in a meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials involving a total of 578 patients who met the diagnostic criteria for an acute depressive or anxiety episode [2]. The data show that mindfulness training in the form of MBCT has a significant effect on depression compared to the control group (with an inactive control) and provided evidence that MBCT works similarly to group-based cognitive behavioral therapy (active control). For anxiety disorders, there was no benefit of MBCT. The authors recommend that MBCT can be offered to patients with an acute depressive episode along with other evidence-based interventions, including to expand their treatment choices.

Regarding the use of mindfulness therapy for anxiety disorders, the speaker referred to the study by Koszycki et al. The study group compared the therapeutic effect of an 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program with a 12-week cognitive group-based behavioral therapy (KVGT) program [3]. In this regard, KVGT was significantly superior to MBSR in reducing social anxiety, rate of responders (67 vs. 39%), and rate of remission (44 vs. 9%). However, in terms of improvement in mood, functionality, and quality of life, the two therapies were found to be comparable. Thus, it is clear to the authors that KVGT remains the treatment of choice for social anxiety disorder. With this result in mind, it can be considered to what extent individual patients would benefit from additional MBSR in terms of improvement of quality of life, Prof. Rufer points out.

Recent studies are trying to figure out what the exact mechanisms of action of mindfulness therapy are. In a review [4], the domains of mindfulness and repetitive negative thinking (rumination) were singled out as mediators of the effects of mindfullness-based therapies. However, methodological weaknesses in some included studies were criticized by the authors.

Neurobiological correlate

How and whether the use of mindfulness-based applications manifests in a neurobiological correlate has been investigated by, among others, Lazar et al. examined. In this study, changes in brain structures were detected in 20 subjects with extensive meditation experience using MRI scans [5]. Brain areas responsible for sensory processing, attentional regulation, and interoception were thicker in meditating subjects than in matched controls.

In another study, functional MRI was used to investigate activities of brain areas during exposure to negatively afflicted images [6]. The 24 healthy subjects who applied a brief mindfulness intervention had reduced activity in brain areas responsible for processing emotions (such as the amygdala or parahippocampal gyrus) during viewing of the stimuli associated with negative emotions vs. that of neutral images, compared to the 22 controls without intervention. The results indicate effects of mindfulness training in relation to the regulation of these neurobiological activities.

There are already approaches to put these findings into practice. The research group led by Prof. Uwe Herwig, MD, is investigating neurofeedback training to treat patients even more effectively [7]. Here, the subjects lie in an MRI, which shows the patients color-coded (traffic light scheme) brain areas that are activated by viewing negative stimuli. Thus, through various measures (e.g., reassessment of the anxiety-triggering situation), the patient can learn via direct feedback to better deal with these stress-triggering situations. In addition, the method promotes the patient’s self-efficacy, as it demonstrates that the individual has the necessary skills to control anxiety. The goal is to internalize what has been trained to such an extent that it can be applied in everyday life.

Summary and outlook

Over the past decade, mindfulness-based therapy for anxiety and depression has evolved from a marginal position in the therapeutic field to a recognized, empirically based practice. For example, MBCT is listed in guidelines under its classic indication, relapse prevention in depression (NICE, S3). Recent studies now provide evidence that MBCT may also have value in depressive episodes and may be recommended when discontinuing antidepressants. Despite these positive findings, other evidence-based procedures must not be neglected (e.g., exposure therapy for anxiety disorders), Prof. Rufer emphasizes in conclusion.

Source:9th Swiss Forum for Mood and Anxiety Disorders (SFMAD), 12. April 2018, Zurich.

Literature:

- Kuyken W, et al: The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence: results of a randomised controlled trial (the PREVENT study). Health Technol Assess 2015; 19(73): 1-124.

- Strauss C, et al: Mindfulness-Based Interventions for People Diagnosed with a Current Episode of an Anxiety or Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. PLoS One 2014; 9(4): e96110.

- Koszycki D, et al: Randomized trial of a meditation-based stress reduction program and cognitive behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther 2007; 45(10): 2518-2526.

- Gu J, et al.: How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clin Psychol Rev 2015; 37: 1-12.

- Lazar SW, et al: Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport 2005; 16(17): 1893-1897.

- Lutz J, et al: Mindfulness and emotion regulation – an fMRI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2014; 9(6): 776-785.

- Nickl R: Controlling fears. UZH Magazine 2014; 23(2): 12-14. www.news.uzh.ch/de/articles/2014/aengste-konrtollieren.html

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(3): 46-48.