The therapeutic landscape for patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis is changing. In the multifactorial pathogenesis of this chronic recurrent dermatosis, an impaired immune response plays a central role. Biologics and Janus kinase inhibitors target proinflammatory cytokines through different mechanisms of action, thereby providing symptom relief. The choice of the appropriate therapeutic option should be criterion-guided.

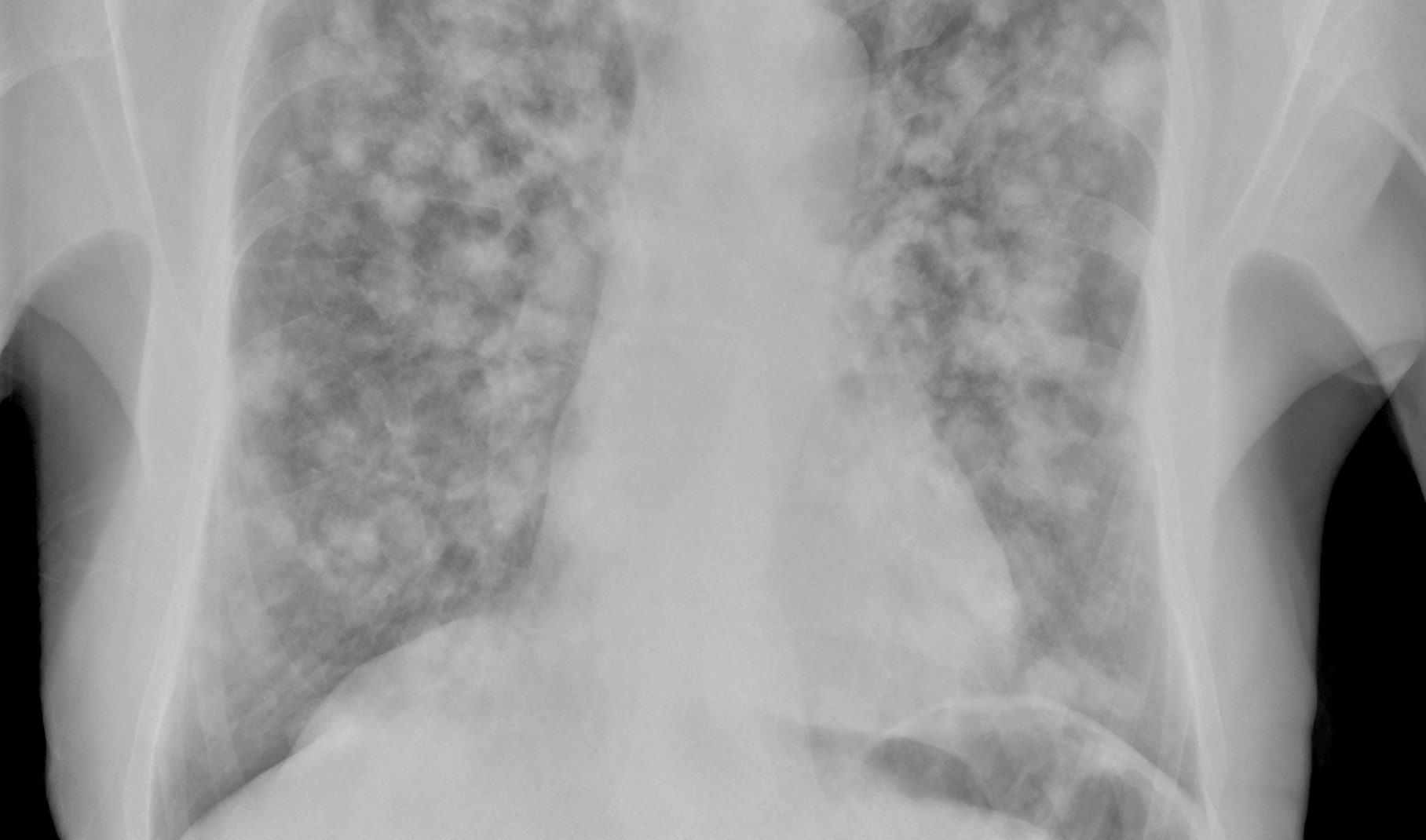

The clinical picture of atopic dermatitis results from complex interactions of genetic factors, barrier defects, a type 2-dominant immune response, and environmental influences [1,2]. Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) is increased in patients with atopic dermatitis, which is associated with xeroderma and severe pruritus. As a result, irritants and allergens can increasingly penetrate the epidermis and thus trigger or intensify inflammation. This can create a vicious cycle of unbearable itching, scratching and further damage to the skin (Fig. 1). On an immunopathological level, atopic dermatitis is characterized by a dominant T-helper type 2(Th2) immune response, dominated in particular by T2 cytokines, such as interleukin(IL)-4 and IL-13, explains Prof. Patrick Brunner, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York (USA) [3,4].

Patient-oriented therapy and regular progress assessment

The treatment goal in patients with atopic dermatitis is primarily to improve itching and inflammatory skin changes. In principle, therapy is tailored to the individual patient and is based on the severity of the disease according to the staging scheme [5]. Consistent basic care with emollients is essential in all stages of the disease, but according to current knowledge, this does not prevent atopic dermatitis, according to the conclusion of a large-scale prevention study in young children [4]. In 60% of cases, atopic dermatitis manifests in the first year of life [6]. Predictors for the persistence of atopic dermatitis into adulthood are an early onset of the disease and comorbidity with other atopic diseases [6]. When local anti-inflammatory measures such as topical glucocorticoids of varying potency and topical calcineurin inhibitors are not effective, patients with atopic dermatitis often require systemic therapy. The Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) can be used to define severity. Below 25 points, atopic eczema is classified as mild, between 25 and 60 points as moderate, and above 60 as severe [7].

Blockade of type 2 inflammation by biologics

The signaling cascades of Th2-mediated inflammation can be stopped with the help of modern biologics. At the latest since the market approval of Dupilumab, it is considered undisputed that type 2 inflammation plays a crucial pathophysiological role in atopic dermatitis, according to Prof. Brunner [3,8]. Dupilumab binds to the common α-subunit of the IL-4 and IL-13 receptors and subsequently inhibits IL4/IL13 signaling. Both cytokines are important drivers of diseases underlying type 2 inflammation. However, not only dupilumab significantly reduced the inflammatory processes in the placebo comparison, but also tralokinumab – this monoclonal antibody, which is specifically directed against IL-13 and prevents its binding to the receptor, has now also received approval in the indication area of atopic dermatitis [8,9]. Another drug candidate is lebrikizumab. This biologic prevents IL-13 signaling by binding to an IL-13 epitope that prevents the IL-13/IL-13Rα1 complex from forming a heterodimer with IL-4Rα [9].

However, in addition to IL-4 and IL-13, other components play a role; this is being intensively researched, for example, in relation to itch in atopic dermatitis [3]. Increasingly, more is known about the mediators involved in it. It appears to be a largely histamine-independent type of pruritus; antihistamines have not been shown to be very effective in most cases. In contrast, studies showed an antipruritic effect by the anti-IL-31 receptor antibody nemolizumab. In contrast, according to current knowledge, dermal inflammation is rather little influenced by nemolizumab, according to Prof. Brunner [3].

Inhibition of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway by Janus kinase inhibitors.

A lot has happened not only in the field of biologics, but also in the field of Janus kinase inhibitors (JAK-i). Unlike biologics, JAK-i are small molecules. With baricitinib (JAK1/2-i), upadacitinib (JAK1-i), and abrocitinib (JAK1-i) as systemic therapeutics, three orally administrable JAK-i are currently approved in Switzerland for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis [8]. Inhibitors of Janus kinase suppress the intracellular cytokine response (JAK-STAT mechanism). Central cytokines in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis that initiate their cytokine response via the JAK-STAT pathway are IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31 [10]. The question of which systemic treatment option is appropriate for which patient is becoming increasingly important. What is particularly interesting about JAK-i as a therapeutic option is its rapid onset of action. With regard to the side effect profile, compared to biologics, infections occur more frequently and certain laboratory parameters are altered during therapy, so that intensive monitoring of patients is necessary. The side effect profile of JAK-i is compound- and dose-dependent.

Research has more arrows in its quiver

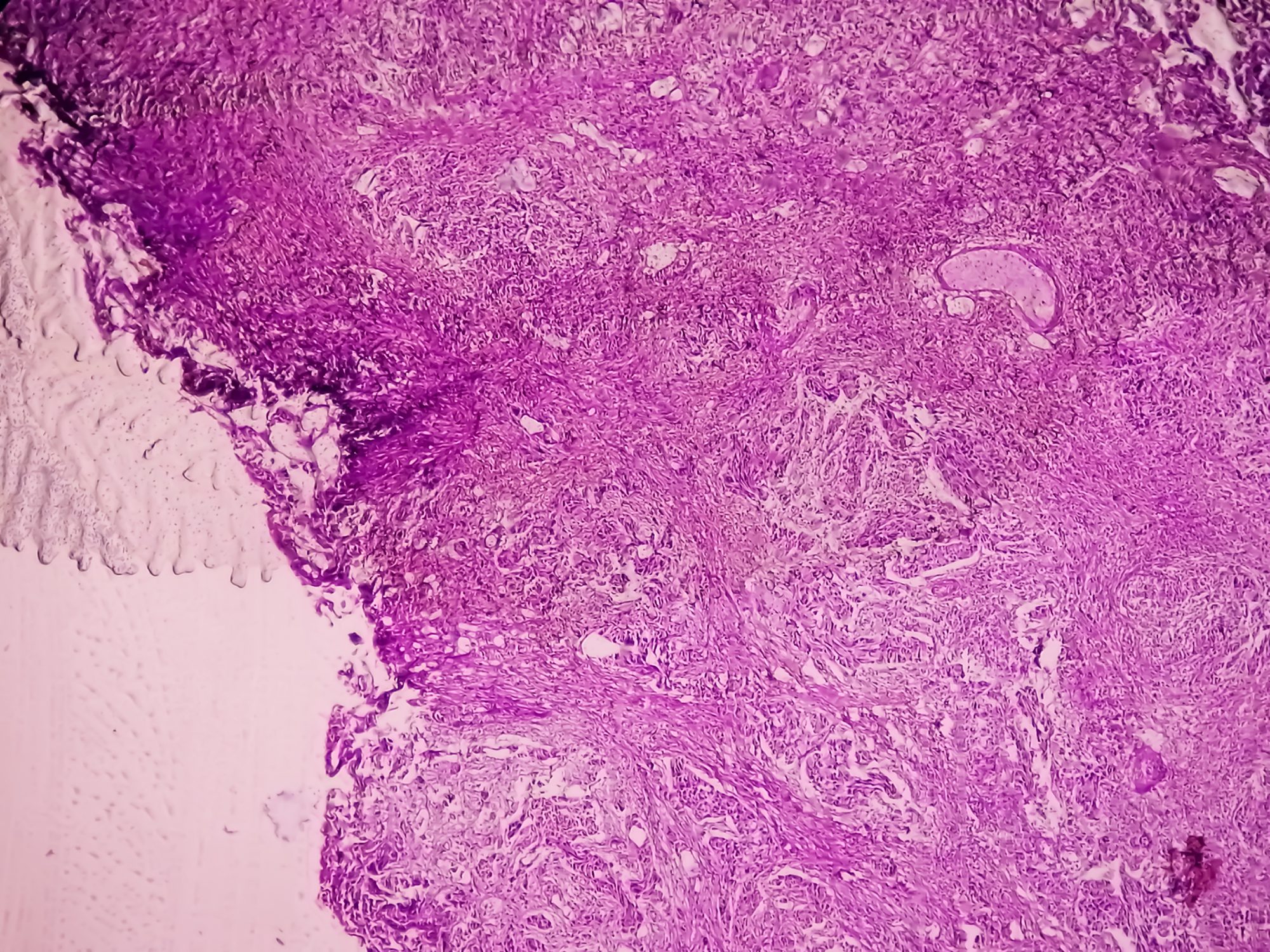

Against the background that symptoms of atopic dermatitis often return after cessation of immunomodulatory system therapy, another focus of research is the analysis of immunological memory. In an observational study published in 2021 in the journal Science Immunology , patients who had been successfully treated with dupilumab were studied using multi-omics technologies such as single-cell RNA sequencing [11]. Specific immune cell populations were identified that indicate persistent disease memory and that enable a rapid response system of “cross-talk” between keratinocytes, dendritic cells, and T cells.

Other approaches currently being explored include antibody therapy directed against TSLP. TSLP (thymic stromal lymphoprotein) is an epithelial cell-derived cytokine produced in response to proinflammatory stimuli and is increased in lesional skin of patients with atopic dermatitis [18]. In addition, studies to date on a monoclonal antibody against OX40, a costimulatory receptor on activated T cells, have been promising [18].

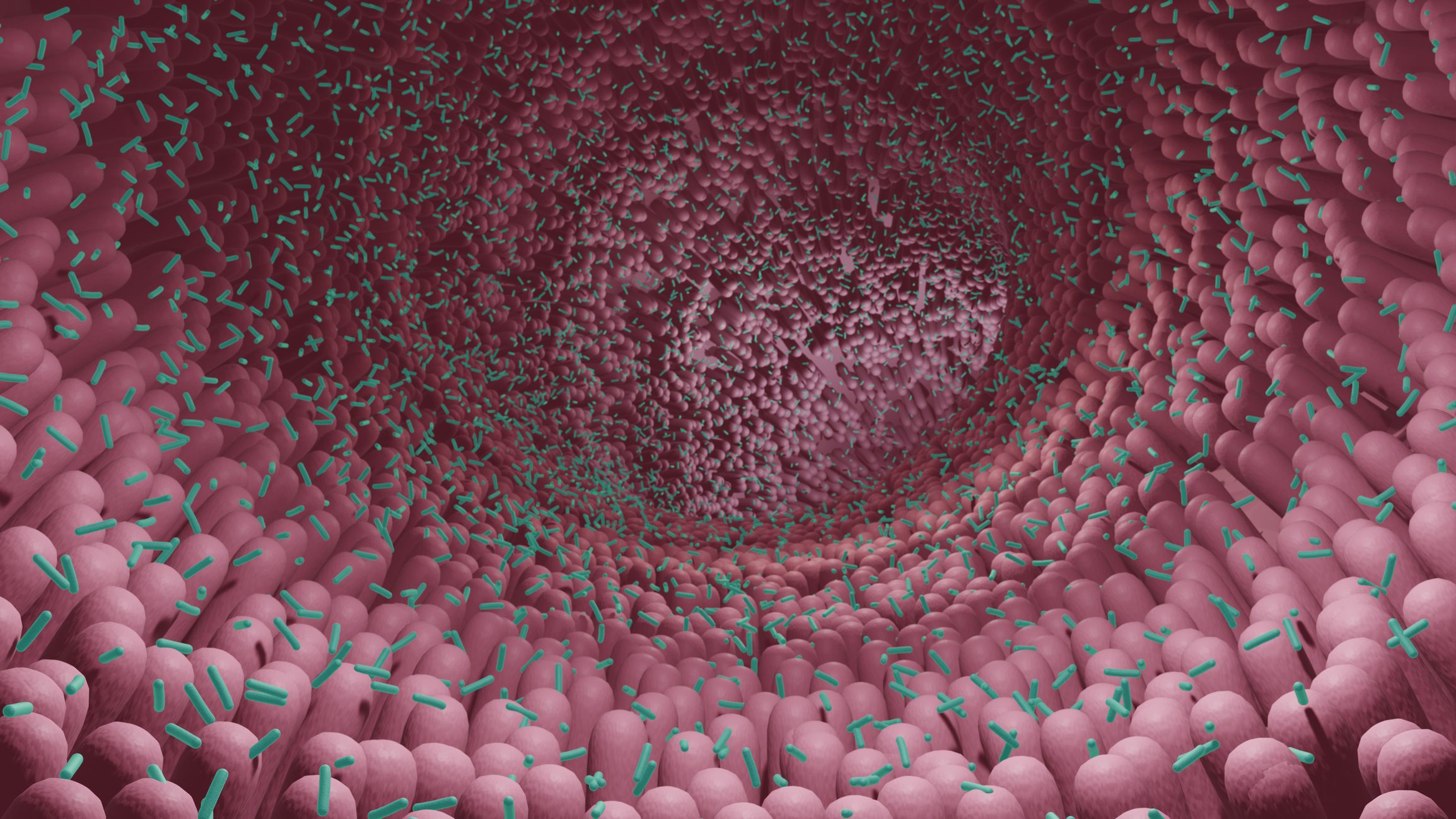

Another possible starting point for the treatment of atopic dermatitis relates to the characteristic dermal dysbiosis. In particular, during an acute episode, a greatly reduced bacterial diversity and the dominance of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) can be observed [12]. One explanation for superinfection with S. aureus is that not enough antimicrobial peptides are produced, explains Prof. Brunner. That local application of antimicrobial skin microbes reduces S. aureus colonization in individuals with atopic dermatitis confirms this concept [13].

Congress: EADV Annual Meeting

Literature:

- Elias PM, Wakefield JS: Could cellular and signaling abnormalities converge to provoke atopic dermatitis? J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2020; 18: 1215-1223.

- Traidl S, Werfel T, Traidl-Hoffmann C: Atopic Eczema: Pathophysiological findings as the beginning of a new era of therapeutic options. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2021 doi: 10.1007/164_2021_49

- “New treatments for atopic dermatitis,” Presentation ID D2T01.2A, EADV Annual Meeting, Prof. Patrick Brunner, MD, Sept. 09, 2022.

- Chalmers JR, et al; BEEP study team. Daily emollient during infancy for prevention of eczema: the BEEP randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020 21; 395(10228): 962-972.

- Wollenberg A, et al: Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 657-682.

- Guideline (S2k) Neurodermatitis Long Version Version 2014, AWMF Register Number: 013-027, www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/013-027l_S2k_Neurodermitis_2020-06-abgelaufen.pdf, (last accessed 09/12/2022).

- Deutsche Haut- und Allergiehilfe e.V., www.dha-neurodermitis.de/therapie/grundlagen-der-therapie.html, (last accessed Sept. 12, 2022).

- Drug Information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch, (last accessed Sept. 12, 2022).

- Wollenberg A, et al: Tralokinumab in atopic dermatitis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2021; 19(10): 1435-1442.

- Klein B, Treudler R, Simon JC: JAK inhibitors in dermatology – small molecules, big impact? Overview of mechanism of action, study results, and potential adverse effects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2022; 20(1): 19-25.

- Bangert C, et al: Persistence of mature dendritic cells, TH2A, and Tc2 cells characterize clinically resolved atopic dermatitis under IL-4Rα blockade. Sci Immunol 2021; 6(55): eabe2749.

- Fölster-Holst R: The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis – correlations and consequences. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2022; 20(5): 571-578.

- Nakatsuji T, et al: Antimicrobials from human skin commensal bacteria protect against Staphylococcus aureus and are deficient in atopic dermatitis. Sci Transl Med 2017;9: eaah4680.

- Rerknimitr P, et al: The etiopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis: barrier disruption, immunological derangement, and pruritus. Inflamm Regener 2017; 37: 14.

- Worm M, et al: Modern therapy of atopic dermatitis: biologics and small molecule drugs. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020; 18(10): 1085-1093.

- Augustin M, et al: Neurodermitis: Information for patients and interested parties, Online at: tk.de, search number: 2099546.

- Werfel T, et al: Cellular and molecular immunologic mechanisms in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138(2): 336-349.

- Quint T, Bangert C: Biologics therapy of atopic dermatitis. close up 2021; 20, 37-44.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2022; 32(5): 24-26 (published 10/25-22, ahead of print).