Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas have become significantly more important in recent years. This is related to the increasing use of imaging such as CT abdomen and MRI, whereby NET of the pancreas are usually discovered as incidental findings. PancNENs account for about 3% of all pancreatic neoplasms, of which about 20% are functional and 80% non-functional tumors.

You can take the CME test in our learning platform after recommended review of the materials. Please click on the following button:

Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas have become significantly more important in recent years. This is related to the increasing use of imaging such as CT abdomen and MRI, whereby NET of the pancreas are usually discovered as incidental findings. Various famous personalities such as Steve Jobs (1955–2011) and Aretha Franklin (1942–2018) have died from pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas.

PancNENs account for about 3% of all pancreatic neoplasms, of which about 20% are functional and 80% non-functional tumors. In the USA, the incidence of PancNET rose from 0.27 to 1.0/100,000 cases per year between 2000 and 2016. According to studies by the National Cancer Institute, the incidence of PancNET with a diameter of 1.1-2.0 cm increased by over 700% in a 22-year interval. 68Ga-DOTATOC PET-CT is playing an increasingly important role in the diagnosis of this tumor entity. The most important prognostic factor for these tumors is the Ki-67 value.

| Abbreviations |

| PancNEN: Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasia |

| PancNET: Neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors |

| PancNEC: Neuroendocrine pancreatic carcinomas |

Known risk factors for the development of a neuroendocrine pancreatic tumor are smoking, increased BMI, gallbladder disease, ethyl abusus and diabetes mellitus. These tumors also occur more frequently in the context of hereditary syndromes such as MEN 1, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome and TSC (tuberous sclerosis).

This article provides an overview of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and focuses primarily on the treatment of benign hormone-active tumors (insulinoma) and the importance of surgery for low grade PancNET (G1, G2) without metastases with a diameter of 1.1–2.0 cm.

WHO classification of PancNEN and overview

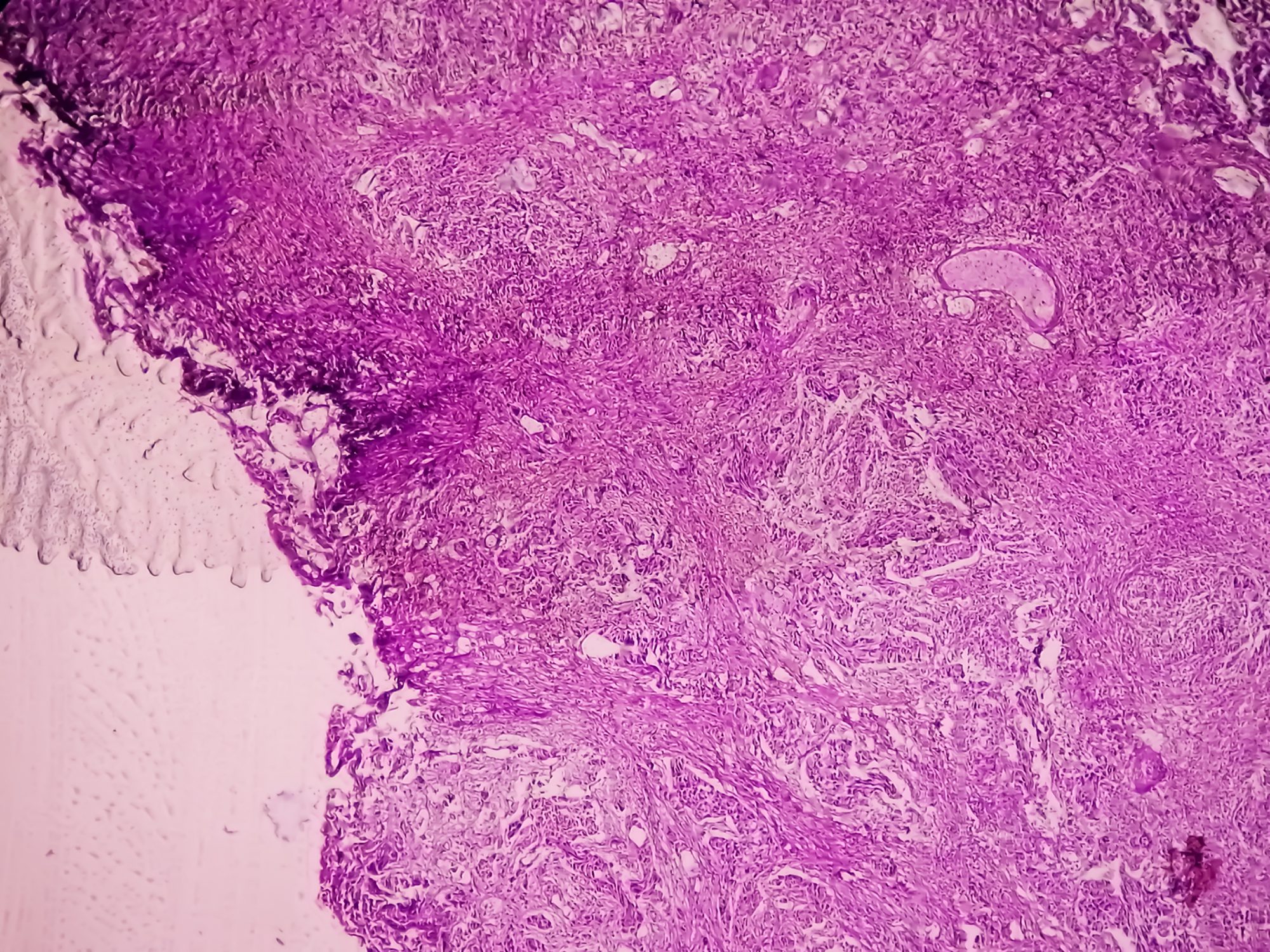

PancNENs were previously classified into well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NET) and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NET) based on their histopathological morphology [1]. Molecular differences can be seen in the detection of various mutations such as TP53 or RB1. In recent years, a clinically more meaningful classification according to WHO 2010 has been established. The WHO classification of these tumors was last revised in 2019 [2] (Table 1).

This classification system combines tumor size, lymph node and distant metastasis status with descriptive histological criteria based on a KI-67 index to generate different subgroups. The pancreatic NET comprises three subgroups G1 to G3, histologically well differentiated, whereby G3 stands out from the other two groups due to a high mitotic rate of >20 mitoses/2 mm² and an AI index >20%. However, a G3-NET generally still behaves less aggressively than PancNEC. These are further subdivided into a small-cell type and a large-cell type. Figure 1 provides an overview of the different tumor types and the corresponding treatment options.

Examples of functional PancNET are most frequently insulinomas, followed by rare tumor entities such as glucagonoma, vipoma, gastrinoma, and somatostatinoma. In the case of non-functional PancNET, treatment is generally based on the grading and size of the tumor. For G₁ and G₂ tumors with a diameter of less than 1 cm, the “watchfull waiting” strategy is now established. G₃ tumors or G1.2 >2 centimeters are usually resected, usually with a corresponding local lymphadenectomy.

The best treatment option for PancNET G1.2 with a diameter of 1.1-2 centimeters is still the subject of heated debate. In metastatic PancNET, liver transplants are occasionally performed after initial resection in accordance with the Milan NET criteria listed in Figure 1.

Insulinomas

90% of these functional tumors are benign and should be resected if possible. If possible, local enucleation is the best surgical procedure with significantly less parenchymal loss than a formal pancreatic resection (Fig. 2). Whether enucleation is technically possible depends primarily on the distance to the main pancreatic duct (Wirsungian duct). However, the postoperative fistula rate after local enucleations is significantly higher in the literature than after formal pancreatic resections.

If the insulinoma cannot be enucleated locally for technical reasons, a duodenopancreatectomy or distal pancreatic resection must be performed, depending on the location. If the insulinoma is located in the corpus area, a central segment resection is also an option (Fig. 3).

Low-grade PancNET G1, G2, non-metastatic

In contrast to functional neuroendocrine benign tumors, for which resection is usually indicated, the size of the tumor plays the most important role in low-grade PancNET.

The guidelines for tumor sizes under 1 cm and over 2 cm are relatively clear. If the tumor size on imaging is less than 1 cm, a “watchfull waiting” strategy is recommended. Surgical resection is generally recommended for tumors with a clear size of more than 2 cm, provided there are no relevant patient-related risk factors. However, if the measured tumor size is between 1.1 and 2.0 cm, the guidelines of the various societies differ in their recommendations or in some cases remain very unclear.

The American guidelines at the NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) have adapted their 2021 guidelines and recommend surveillance for tumor sizes of 1–2 cm [3]. The ENETS (European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society) also recommends surveillance [4], while the Japanese Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (JNETS) recommends resection in these cases. The ESMO (European Society for Medical Oncology) recommends resection in a young patient with dilatation of the main pancreatic duct or when symptoms occur [5]. There are several studies that speak for or against the resection of a low-grade Pan NET G₁ or G₂.

In an analysis of the National Cancer Database in the USA from 2004–2014, all PancNET smaller than 2 cm were identified [6]. Approximately 70% of newly diagnosed malignant tumors in the USA are recorded in this database. Of a total of 3243 patients with a PancNET <2 cm, 78.7% were resected. There was a clear survival advantage with a surgical procedure in the entire cohort with a five-year survival of 89.1% versus 60.1% in the group with a conservative procedure. A multivariate survival analysis confirmed the survival advantage, which was statistically significant. In their study, the authors called for further prospective studies on resection versus primary observation of PancNET smaller than 2 cm.

A systematic review published in 2017 [7] also analyzed the course of these tumors in an observation group versus resected patients. A total of 540 patients from five retrospective studies were included in this meta-analysis. 60.6% were under active observation, while 39.4% underwent surgery. Of the conservative group, 14.1% underwent surgery after initial conservative management, mostly due to an increase in size. There was not a single tumor-related death in the observation group. The conclusion from this study was that active surveillance is a good alternative to surgical treatment in patients with a small asymptomatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor.

There are two prospective multicenter studies for patients with a PancNET <2 cm. The PANDORA trial [8] is a national prospective cohort study of the Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group that included 76 patients with a PancNET <2 cm between 2017 and 2020. During a median follow-up of 17 months, 89% showed no signs of tumor progression, while 11% showed progression between 0.5 cm and 2.0 cm. The conclusion from this study was that an observation protocol successfully prevented surgical resection in 9 out of 10 patients.

The second study is the ASPEN trial [9], which published an interim analysis in 2022. This prospective, non-randomized, international multicenter study from 41 centers included all PancNET patients with a tumor diameter of <2 cm. The diagnosis had to be confirmed by either a fine needle biopsy or a 68GA-labeled DOTA PET-CT. Distant metastases were present in four patients (0.08%). The therapeutic decision for an operation or observation was left to the individual centers or the patient. The conclusion of this study was that active surveillance is the best option for patients with a sporadic, asymptomatic tumor <2 cm. After a median follow-up of 25 months (16-35 months), all patients were still alive except for 3 who died of non-tumor-related causes.

Indications for surgery – especially in younger patients – are the presence of measurable increases in size or a dilated main pancreatic duct. The latest study on this topic – published in JAMA 2023 [10] – examined the survival rates after surgical resection of small non-functional neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors. This was a cohort study from the National Cancer Database 2004-2017. From a total group of 10 504 patients, 4641 patients met the criteria for PancNET with a tumor diameter <2 cm. Two groups were formed with tumor diameters of less than 1 cm and tumor diameters of 1.1-2.0 cm. The 5-year survival rates were compared with non-operated patients with the same tumor size. In the group with tumor size <1 cm, the 5-year survival rate was 82.8% in the non-operated group versus 88.3% in the operated group. In the second group with tumors between 1.1-2.0 cm, the 5-year survival rates were significantly higher in the operated group (92.3%) than in the observation group (76.0%). The conclusion of this study was that surgical resection is associated with longer survival for patients with an initial tumor size of 1.1-2.0 cm. In the present study, the distant metastasis rate was 2.3% in the group <1 cm and 4.9% in the group with a tumor diameter of 1.1-2.0 cm.

An interaction analysis showed improved survival especially in patients younger than 64 years, absence of comorbidities, treatment at an academic institution and localization in the pancreatic tail.

In summary, it must be borne in mind that the risk of malignant degeneration for small PancNET is around 5–10% according to the literature. Unfortunately, there is still a lack of prognostic markers that would indicate tumor progression. Most studies with a median follow-up of a maximum of 3–4 years cannot reflect the long-term prognosis well, due to the slow growth of these tumors. The long-term prognosis must be compared with the risk of surgical morbidity and mortality when determining the indication for a surgical procedure.

Risks of pancreatic surgery

When discussing morbidity and mortality in pancreatic surgery with surgeons, “The rule of 2” should be kept in mind:

If you look at the morbidity and, above all, the mortality in pancreatic surgery in published results from highly specialized centers, the mortality rate is generally well below 3-5%.

A study published in 2016 examined nationwide in-hospital mortality following pancreatic resection in Germany [11]. In the period 2009–2013, 58,003 patients who underwent pancreatic resection in Germany were analyzed. The overall in-hospital mortality rate was 10.1% and had not changed significantly over the four-year period. The highest mortality risk of 22.9% was found in the total pancreatectomy group, while the mortality rate in the distal pancreatectomy group was 7.3%.

These high mortality rates following this complex surgery are the main reasons for the efforts to centralize such complex procedures. It has been proven that morbidity and mortality rates are significantly lower in centers with a higher caseload. In Switzerland, this has also led to pancreatic surgery only being allowed to be performed at 18 hospitals as part of HSM (highly specialized medicine).

The most feared complication after pancreatic resection is pancreatic fistula, which still occurs with a relatively high incidence even at highly specialized centers. Especially after a distal pancreatectomy, the incidence of a postoperative pancreatic fistula is between 25 and 35%. Risk factors are a soft pancreas, a high BMI and a narrow main pancreatic duct. In 2016, an international study group classified the severity of pancreatic fistula [12]. Type A fistula is a biochemical leak with an amylase value in the drainage fluid that is three times higher than the upper normal value of serum amylase. This fistula usually requires no further treatment. If the drainage fluid persists for more than 3 weeks and measures such as percutaneous or endoscopic drainage or angiography are necessary, this is a type B fistula. Type C fistula is defined by a fistula-related necessary re-operation, organ failure or even death of the patient due to the fistula complications.

The most feared complications of fistula, apart from infection, are arterial bleeding of the upper abdominal vessels such as the common hepatic artery, lienal artery or gastric artery. Various techniques have been developed in recent decades to minimize the risk of pancreatic fistula. The optimal procedures for treating the pancreatic remnant after a distal left resection are the subject of heated debate. If the pancreas is closed using a stapler or manual suture, various adhesive materials such as fibrin glue or patches (TachoSil) are helpful. or should autologous tissue patches even be used?

The analysis of the question of the best closure of the pancreatic remnant was published in a randomized study in the Lancet 2011 [13]. A group of 352 patients were randomized to forklift sutures versus hand sutures. The morbidity and mortality rates were the same in both groups. The incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula was 32% in the stapler group versus 28% in the hand-stitched group; this result was not statistically significantly different [13]. A network meta-analysis compared different techniques in relation to the risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatic left resection [14]. A total of 1984 patients from 16 randomized controlled trials were included and eight different techniques were compared. The lowest incidence of clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula was found after autologous patch coverage (ligamentum teres flap) of the pancreatic stump. This was confirmed in the DISCOVER study [15]. In this prospective randomized controlled trial, 76 patients with a ligamentum teres patch were compared with a control group of the same size. The rate of interventional and surgical interventions was reduced from 35.5% to 19.7% by covering with a ligamentum teres flap. The overall incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistulas was not statistically significantly different, but there was a significant difference in the incidence of the dreaded type C fistulas. I personally always use an autologous pedicled ligamentum teres flap to cover the pancreatic resection area after a distal left pancreatic resection (Fig. 4).

Take-Home-Messages

- Functional neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors such as insulinomas should be resected whenever possible.

- Non-functional neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors <1 cm can be monitored.

- Non-functional neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors between 1.1-2 cm in diameter can be resected or monitored depending on age, comorbidities, duct involvement (dilatation).

- Non-functional neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors >2 cm are clear indications for resection.

Literature:

- Robinson MD, Livesey D, Hubner RA, et al.: Future therapeutic strategies in the treatment of extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinoma: a review. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology 2023; 15; doi: 10.1177/17588359231156870.

- Nagtegaal ID, et al.: The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology 2020; 76: 182–188; doi: 10.1111/his.13975.

- Benson AB, et al.: NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2023 Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors NCCN Guidelines Panel Disclosures. www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1448

- Falconi M, et al.: ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of patients with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2016; 103: 153–171.

- Pavel M, et al.: Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 2020; 31: 844–860.

- Chivukula S, Tierney J, Hertl M: Operative resection in early stage pancreatic neuroen-docrine tumors in the United States: Are we over- or undertreating patients? Surgery 2020; 167: 180–186.

- Partelli S, et al.: Systematic review of active surveillance versus surgical management of asymptomatic small non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. British Journal of Surgery 2017; 104: 34–41; doi: 10.1002/bjs.10312.

- Heidsma CM, et al.: Watchful waiting for small non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tu-mours: Nationwide prospective cohort study (PANDORA). British Journal of Surgery 2021; 108: 888–891.

- Partelli S, et al.: Management of asymptomatic sporadic non-functioning pancreatic neuroen-docrine neoplasms no larger than 2 cm: Interim analysis of prospective ASPEN trial. British Journal of Surgery 2022; 109: 1186–1190.

- Sugawara T, et al.: Evaluation of Survival Following Surgical Resection for Small Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. JAMA Netw Open 2023; 6.

- Nimptsch U, Krautz C, Weber GF, et al.: Nationwide in-hospital mortality following pancreatic surgery in Germany is higher than anticipated. Ann Surg 2016; 264: 1082–1090.

- Bassi C, et al.: The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grad-ing of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery 2017; 161: 584–591.

- Diener MK, et al.: Efficacy of stapler versus hand-sewn closure after distal pancreatectomy (DISPACT): a randomised, controlled multicentre trial. The Lancet 2011; 377: 1514–1522.

- Ratnayake CBB, et al.: Network meta-analysis comparing techniques and outcomes of stump closure after distal pancreatectomy. British Journal of Surgery 2019; 106: 1580–1589.

- Hassenpflug M, et al.: Teres Ligament Patch Reduces Relevant Morbidity After Distal Pancreatectomy (the DISCOVER Randomized Controlled Trial). Ann Surg 2016; 264: 723–730.

InFo ONKOLOGIE & HÄMATOLOGIE 2024; 12(5): 6–11