Treatment of MS, the autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that most often leads to disability in young adulthood, has made many small advances over the past two decades, as well as some major ones. The therapeutic landscape has changed significantly, so that different therapeutic options with different mechanisms of action are now available.

Multiple sclerosis cannot yet be cured, despite many therapeutic advances, but it can often be controlled. Treatment of the autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that most commonly leads to disability in young adulthood has made many small and also some larger advances over the past two decades, and the therapeutic landscape has changed significantly so that different therapeutic options with different mechanisms of action are now available. Thus, the heterogeneity of the disease and the characteristics and needs of the individual patient can be better addressed.

Since the end of 2020, a new drug for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) has been approved in Switzerland, which will be discussed in more detail in this CME article. This is ozanimod, a selective sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator that binds specifically to S1P receptor subtypes 1 and 5. As a result, the lymphocytes are retained in the periphery and can no longer interfere with the inflammatory process in the central nervous system (CNS); moreover, additional mechanisms of action in the CNS are potentially conceivable. The drug is approved in Switzerland as first-line therapy in adult RRMS patients.

The mechanism of action of Ozanimod in brief

In MS, the entry of certain inflammatory cells across certain barriers into the central nervous system (CNS) represents a key point that can be influenced with Ozanimod. Ozanimod as a selective sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator retains these inflammatory cells in secondary lymphoid organs (such as lymph nodes or spleen). Binding of ozanimod to S1P receptors on immature lymphocytes leads to activation and internalization of these receptors. As a result, the exit of lymphocytes from the lymph nodes into the bloodstream is inhibited, reducing the number of lymphocytes in the blood and preventing them from interfering with the inflammatory process in the CNS; other direct CNS mechanisms of action, e.g., on glial cell function, are also conceivable.

Difference to other S1P receptor modulators

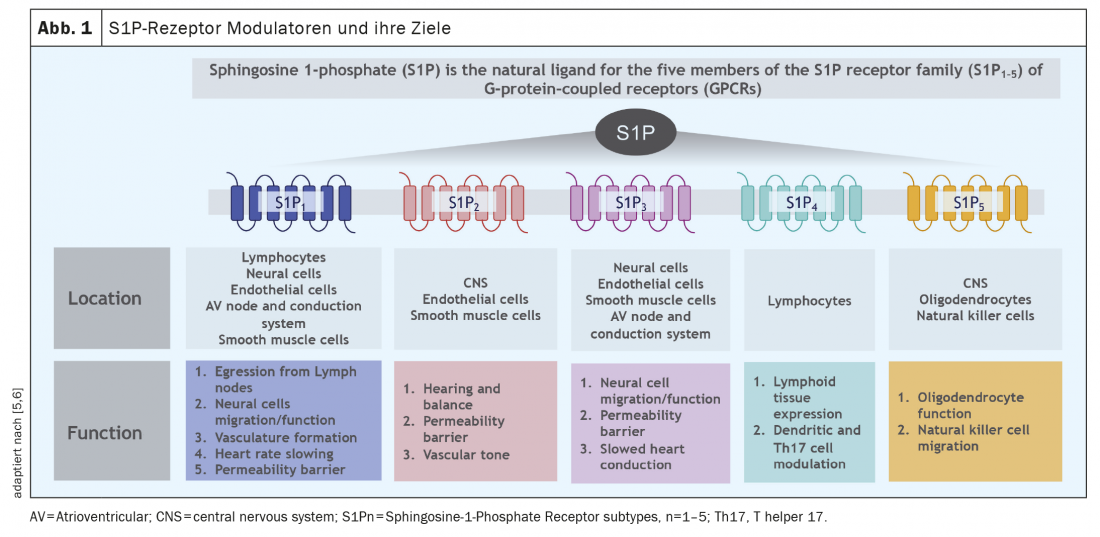

In addition to ozanimod, there are two other S1P receptor modulators in the Swiss MS therapy landscape: Fingolimod and siponimod. A common feature of these compounds is binding to the S1P receptors, with varying selectivity to the individual receptor subtypes depending on the compound. Whereas ozanimod binds highly selectively to the S1P1 and S1P5 receptor subfamily, fingolimod does not bind selectively to two chosen ones, but more nonspecifically to all 5 S1P receptor subtypes, to the S1P2 receptor with low affinity (see below). However, depending on the cell and tissue, the subtypes of S1P receptors are expressed differently; an overview of the distribution of these receptors is given in Figure 1. In summary, S1P1 receptors are mainly found on lymphocytes, whereas the S1P5 receptor is mainly expressed in the CNS. Thus, selective binding to these receptor subtypes also makes pathophysiological sense. Like ozanimod, siponimod binds selectively to S1P1 and S1P5 receptors, but the drugs differ in pharmacokinetics (ozanimod is largely degraded into 2 active metabolites within hours) and possibly also in selectivity for receptor subtypes, as ozanimod binds selectively with high affinity in vitro, particularly to S1P1 and less to S1P5 receptors [1].

Endpoints of effective MS therapy

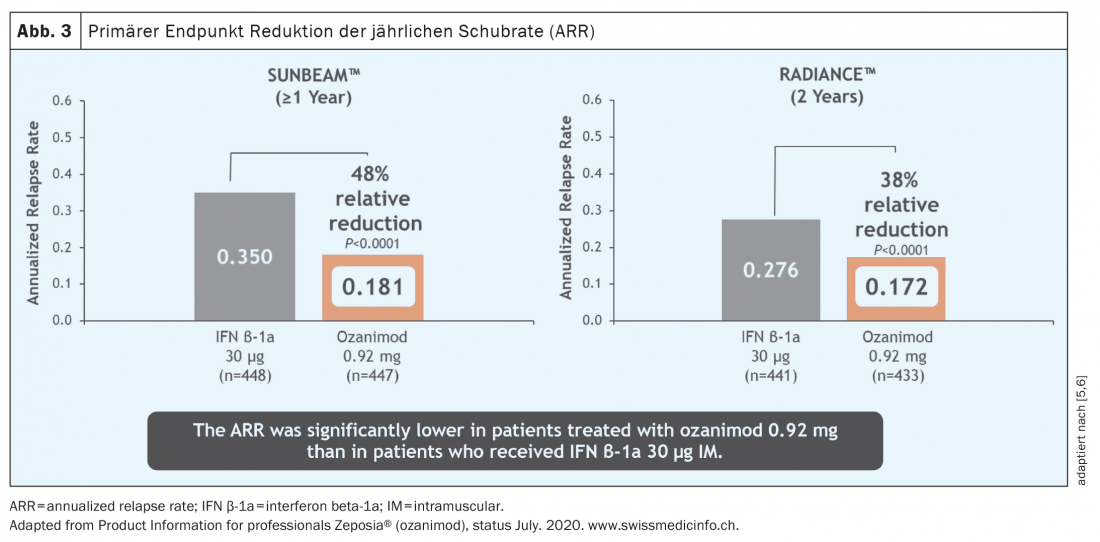

Today, thanks to effective immunotherapies, higher therapeutic goals can be set than anticipated a few decades ago. A common concept, especially in therapy studies, is the “No Evidence of Disease Activity” (NEDA) concept [2,3].

Hereby

- No MR activity (new and/or enlarging T2 hyperintense lesions and/or T1 contrast-enhancing lesions),

- no thrust events,

- No creeping progression in the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) (“NEDA3”) [2–4] and frequently also

- no brain atrophy defined as treatment targets (“NEDA 4”) (Fig. 2) [2– 5].

However, quantitative brain atrophy measurement has not been regularly performed in clinical practice so far due to methodological and technical difficulties [10,11]. Furthermore, the NEDA 3 concept is mainly driven by imaging activity, which has to be considered critically from a clinical point of view. In clinical practice, the focus has so far been on endpoints that can be regularly objectified without much effort, such as the EDSS, but more attention is also being paid to aspects such as cognition or fatigue. Increasingly, (cranial) MRI is included as a sensitive tool for efficacy and safety assessment. In the future, quantitative brain atrophy measurement (e.g., thanks to automated segmentation of brain sections by “machine learing”) is likely to gain increased entry into clinical routine in the medium term [11].

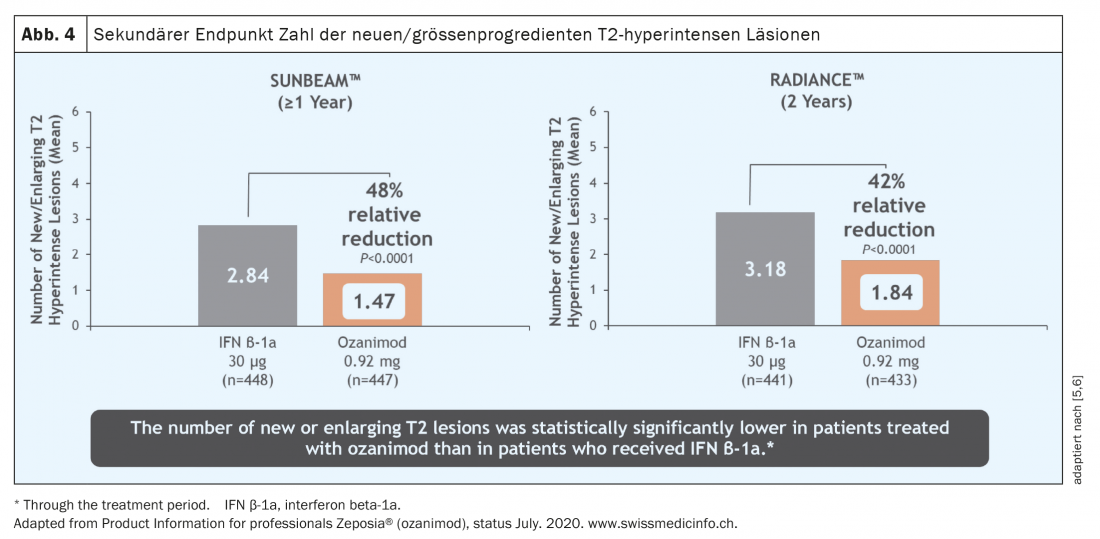

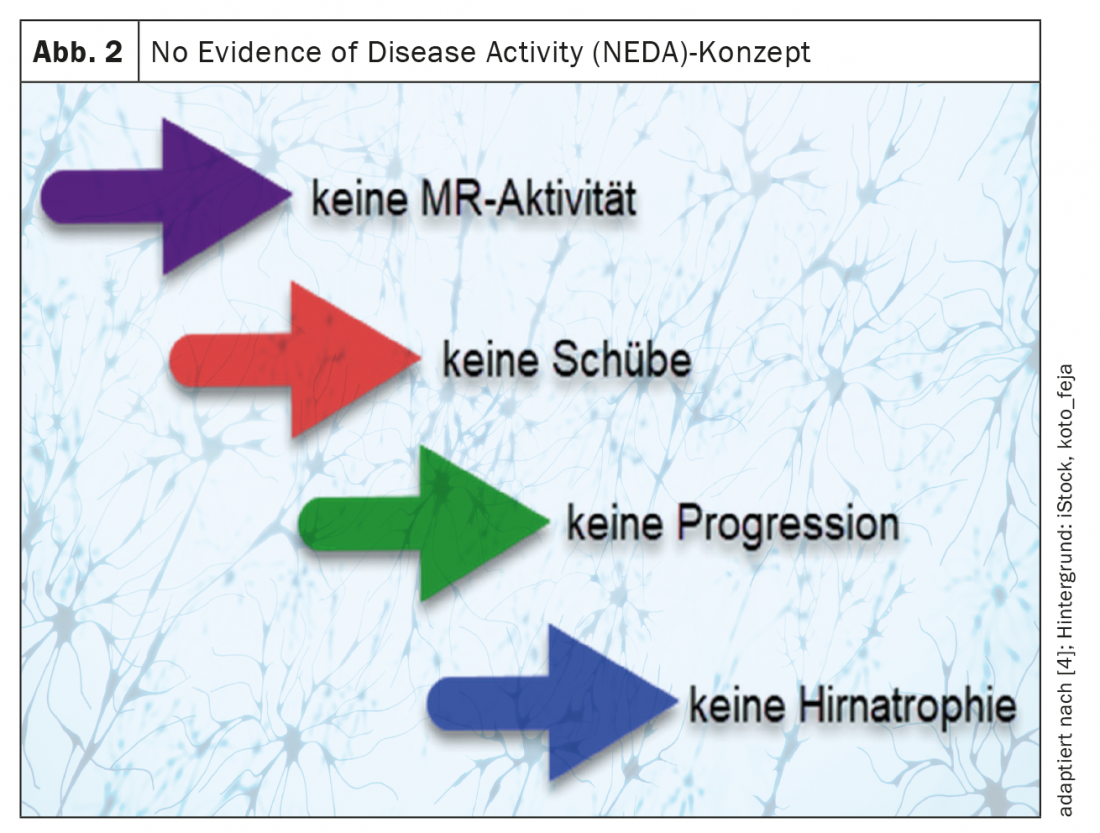

With regard to the study data, the study quality is also particularly important. In the case of ozanimod, for example, two different large studies were conducted in parallel. If, as in the case of ozanimod, both studies come to essentially the same results, then a robust study situation can be assumed. The two studies relevant for approval, RADIANCE [5] and SUNBEAM [6], are multicenter, double-blind, double-dummy phase 3 studies comparing ozanimod with the active comparator interferon beta1a and differ mainly in the different observation periods of 24 and 12 months, respectively.

Ozanimod efficacy

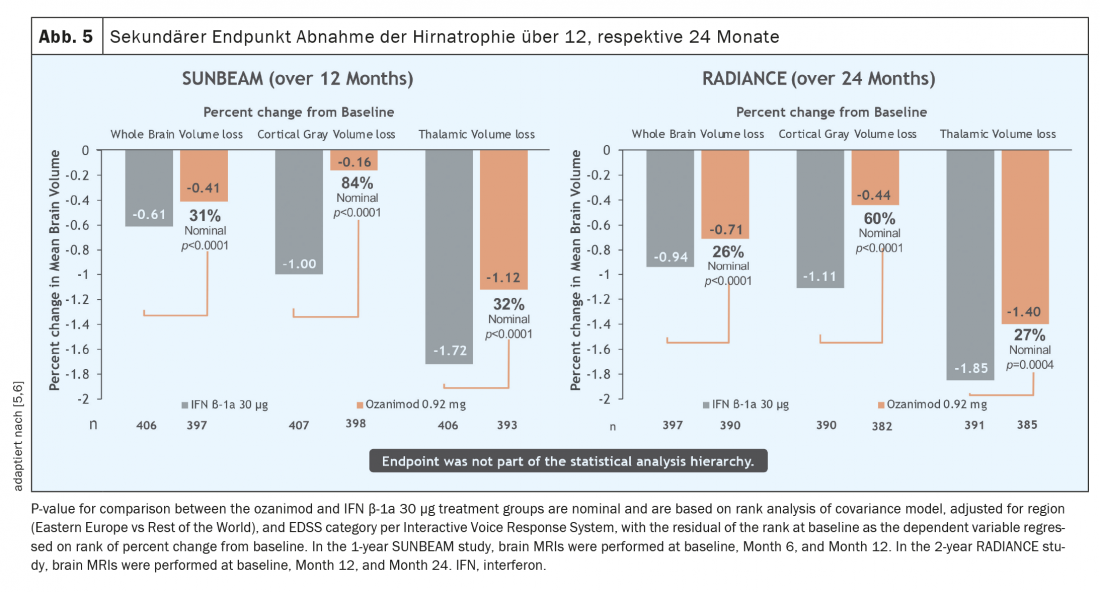

Over a period of both one and two years, the relapse rate was significantly reduced in a patient population active before the start of therapy (Fig. 3) [5 – 7]. It must be emphasized that in these studies ozanimod was not tested against placebo but against an active comparator (interferon beta-1A Avonex®), which highlights the clinical efficacy of ozanimod. In addition, a significant reduction in MR-tomographically detectable inflammatory activity was observed (Fig. 4) . However, over the rather short study duration of 12 and 24 months, respectively, no effect on disability progression could be demonstrated. However, initial MR tomographic data from both studies showed an effect in terms of whole brain atrophy, thalamic atrophy and cortical atrophy (Fig. 5) . A faster cognitive processing speed was also observed in ozanimod patients than in the comparison group, providing initial evidence for a possible positive effect also on cognitive endpoints. Thus, in the pivotal studies of ozanimod, “newer” endpoints such as cognition and atrophy were included in addition to “classic” endpoints such as T2 lesion burden and relapse events. It should be noted, however, that in these studies the atrophy measure was only a secondary endpoint and cognitive processing speed was an exploratory endpoint, so these results must be viewed with some caveats. Here, long-term data will provide more accurate results.

Side effects

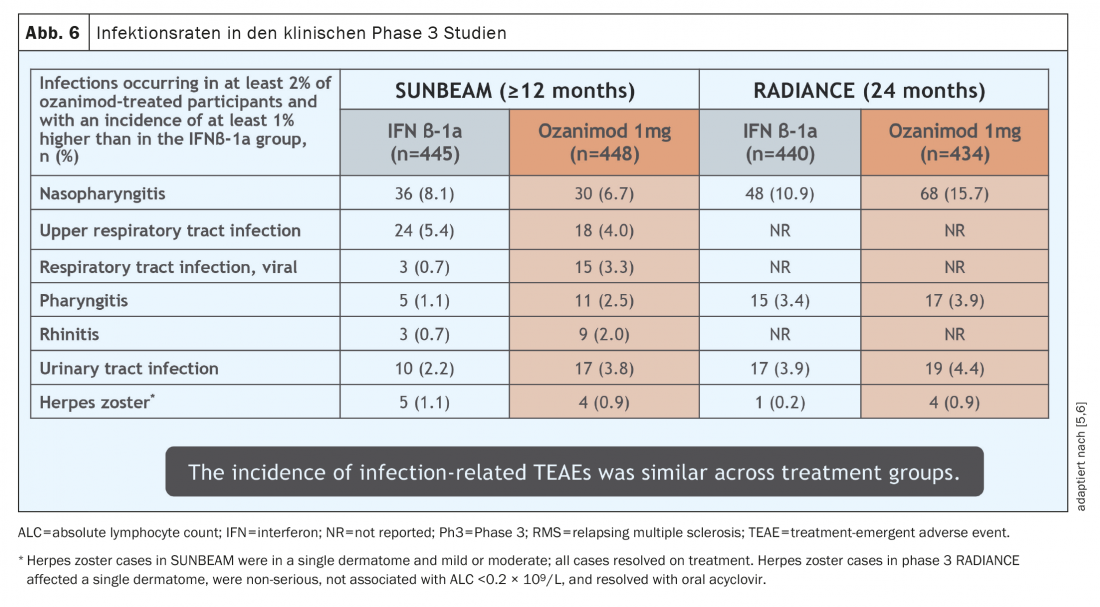

The side effects experienced with ozanimod use in the pivotal studies were essentially consistent with experience with other SP1-addressing agents that have been on the market for many years. The most common side effect detected was a slight increase in respiratory and urinary tract infections (Fig. 6) . These infections all took a mild course. In a few cases (0.1- 0.3%), macular edema occurred in patients with pre-existing conditions (uveitis, diabetes mellitus, or underlying/co-existing retinal diseases) at increased risk, and herpes zoster was observed in 0.6%. According to the mechanism of action, lymphocyte reduction in peripheral blood is approximately 45-50%, but this is not a side effect per se due to the mechanism of action of ozanimod with retention of lymphocytes in secondary lymphoid organs.Transient grade 4 lymphopenia according to CTCAE occurred in 2.5-4.2% of patients in the pivotal studies (<0.2 G/l), but these were not associated with increased infections and did not lead to discontinuation of therapy. There is no signal so far toward opportunistic diseases, yet more and longer data are needed for further assessment. Importantly, in pivotal trials, elevated liver parameters (defined as >3× upper normal value) occurred in 5- 6% of patients, requiring discontinuation of therapy in 1.1% of patients [5,6]. It should be noted that none of these cases to date met Hy’s law, which describes the likelihood that liver failure can be attributed to a specific medication [12].

To minimize cardiac side effects, ozanimod is titrated up gradually over 7 days. As a result, sinus tachycardia occurred in 2 pa-tients (0.5%) and sinus bradycardia in one patient (0.2%) in the pivotal studies, necessitating discontinuation of therapy in one patient (0.2%).

Contraindications of Ozanimod

The following contraindications should be considered before starting therapy with ozanimod [adaptiert nach 8,9]:

- Hypersensitivity to ozanimod or any of the other ingredients.

- In the last 6 months: Myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack, decompensated heart failure with required hospitalization, or Class III/IV

- History of or current presence of second-degree (type II) atrioventricular (AV) block or third-degree AV block or sinoatrial node syndrome (exception: functioning pacemaker present).

- Severe untreated sleep apnea

- Immunodeficient state

- Increased risk of opportunistic infections, including patients currently receiving immunosuppressive therapy or who are immunocompromised

- Severe active infections or active chronic infections (e.g., hepatitis, tuberculosis).

- Active malignant disease

- Severe hepatic insufficiency (Child-Pugh class C)

- Existing macular edema

- Pregnancy

Other safety aspects [adaptiert nach 7,8]

Because the pivotal studies excluded patients with prior immunosuppressive treatments (fingolimod, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, cladribine, ocrelizumab, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, total body irradiation, and bone marrow transplantation), ozanimod should be used with caution in such patients.

When discontinuing therapy with ozanimod, the possibility of serious disease worsening should be considered, as this has been reported in up to 10% of cases after discontinuation of another S1P receptor modulator [13]. However, it is unclear whether this is also true for ozanimod with a different receptor profile and pharmacokinetics.

It is also important to avoid comedication of ozanimod with BCRP (Breast Cancer Resistance Protein) inhibitors (such as cyclosporine), MAO (monoamine oxidase) inhibitors (such as selegiline), and CYP2C8 (cytochrome P2C8) inducers (such as rifampicin) and inhibitors (such as gemfibrozil).

In women of childbearing potential, pregnancy must be ruled out before starting therapy, and effective contraception must be used during treatment with Zeposia and for 3 months after Zeposia therapy is discontinued.

Monitoring before and during therapy with ozanimod [adaptiert nach 8,9]

Prior to initiating therapy, all patients should have liver parameters checked and a differential blood count obtained. In women of childbearing age, pregnancy must also be ruled out and safe contraception installed (indicated until 3 months after discontinuation of therapy).

Further, all patients should have their vaccination status updated. Patients without a medically confirmed history of varicella and without a complete VZV vaccination should be tested for antibodies against VZV and vaccinated if there is no evidence (caveat: live vaccine; completion of vaccination in this case must be at least 1 month before the start of therapy). No clinical data are available regarding the safety and efficacy of vaccination during therapy with ozanimod. Regarding COVID disease and vaccination, despite theoretical concerns based on the mechanism of action, there are no specific safety signals to date regarding ozanimod [14]. According to Swiss and international guidelines, COVID vaccination is recommended in patients on Ozanimod [15,16]. Attenuated live vaccines should be avoided during and up to 3 months after therapy with ozanimod and must be completed at least 1 month before starting therapy.

Before starting therapy, an ECG should be performed in all patients to detect any conduction disturbance. Upon initiation of therapy, six-hour cardiac monitoring with ECG should be performed in selected cardiac risk patients. This is not recommended in patients with resting HR <55 bpm, 2nd degree AV block [Mobitz Typ I] or st.n. Myocardial infarction before >6 months or heart failure indicated. In addition, in patients with St.n. cardiac arrest, cerebrovascular events prior to >6 months, uncontrolled hyper-tonia, recurrent syncope and symptomatic bradycardia, significant QTc prolongation, or treatment with antiarrhythmic drugs, a cardiologic co-evaluation should be performed to determine whether therapy with ozanimod can be initiated and how monitoring should be arranged. In all other patients, unlike fingolimod, six-hour cardiac monitoring is no longer required. However, regular monitoring of blood pressure is recommended for all patients undergoing therapy.

Furthermore, monitoring of liver function tests is indicated before initiation of therapy and in symptom-free patients after 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months (followed by periodic monitoring) [8]. As part of these checks, a differential blood count should also be taken before starting therapy and every 3 months for the first year to avoid missing an excessively severe lymphopenia (followed by periodic checks).

Ophthalmic risk patients with risk factors for macular edema (st.n. uveitis, diabetes mellitus, retinal diseases) should be regularly observed by their ophthalmologist before and during therapy. In the absence of risk factors for macular edema, however, in contrast to fingolimod, ophthalmologic presentation is not necessary prior to initiation of therapy.

In the event of serious infections with ozanimod (which occurred in less than 1% in the pivotal studies), interruption of therapy should be evaluated. Due to the long elimination time (especially of the active metabolites), monitoring for infections should be performed for up to 3 months after discontinuation of therapy.

Practical procedure when adjusting to Ozanimod [adaptiert nach 8,9]

When switching immunosuppressive medications to ozanimod, the duration of action as well as the mechanisms of action of these treatments should be considered to avoid unintended additive immunosuppressive effects. For example, in the case of prior therapy with drugs that reduce lymphocytes, wait for normalization of the lymphocyte count before starting therapy with ozanimod. It should also be noted that in the pivotal studies, prior therapies with fingolimod, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, anti-CD4, cladribine, rituximab, ocrelizumab, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, total body irradiation, and bone marrow transplantation were excluded at any time prior to a patient’s entry into the clinical trial, and consequently no clinical data are available for these patient groups. However, these prior therapies are not defined as contraindications to therapy, so therapy with ozanimod is certainly possible even after these prior therapies; however, the duration of action as well as the mechanisms of action of the prior therapies should be considered to avoid unintended additive immunosuppressive effects. Treatment with ozanimod can usually be started immediately after discontinuation of interferons or glatiramer acetate if there are unremarkable laboratory results (especially differential blood counts and liver enzymes).

At the start of therapy, a dose titration regimen is required from day 1 to day 7. After the 7-day dose titration, the maintenance dose is 0.92 mg orally once daily, taken continuously from day 8. Ozanimod capsules are to be swallowed whole and can be taken with a meal or independently of meals. If a dose of ozanimod is missed, the next scheduled dose should be taken the following day.

Ozanimod’s place in today’s MS therapy landscape.

Ozanimod is approved in Switzerland for the first-line treatment of adult patients with relapsing-remitting MS and may only be prescribed by a consultant neurologist [17]. In contrast to Switzerland, ozanimod may only be used in the EMA region if there are signs of disease activity (clinically, or MR-tomographically), whereas in Switzerland this criterion does not have to be met [8,18]. The study populations included adult RRMS patients with active disease; inclusion criteria required a relapse in the past 12 months, or a relapse in the past 24 months with evidence of a contrast-enhancing lesion on MRI in the past 12 months; in addition, the EDSS had to be less than 5.5. Most patients in the study population already had neurological abnormalities (EDSS scale 2.5 – 2.7) (which, however, is not a prerequisite for therapy with Ozanimod in Switzerland), the average age was around 35 years, and a good two-thirds of the study participants were female. Accordingly, the suitable patient clientele is not a highly selected special patient group, but rather sufferers who are encountered in the consultation on a daily basis. Pretreatment with other drugs also does not preclude therapy with ozanimod (although higher vigilance may be required depending on prior therapy). Post hoc studies did not detect specific patients who did not respond to the S1P receptor modulator, so ozanimod appears to be a therapeutic option for various patient profiles. Ozanimod was well tolerated in the pivotal studies (and now also in the first clinical trials), there are no significant gastrointestinal side effects, and once-daily oral administration is also straightforward. These factors enable patients to integrate the treatment into their daily routine very well, so that there are good prerequisites for a high level of therapy adherence.

Conclusion

Each new compound is a welcome addition to the MS therapist’s armamentarium. MS cannot be cured, but it can often be controlled. However, not every drug works equally well for every patient. Therefore, an individual approach to the person concerned is essential. Here, Ozanimod is another building block to provide patients with an individualized, effective, safe and well-tolerated therapy.

Take-Home Messages

- Multiple sclerosis still cannot be cured today, despite many advances, but it can often be controlled.

- Ozanimod is a selective sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator that binds specifically to S1P receptor subtypes 1 and 5.

- The binding of ozanimod to these S1P receptors prevents lymphocytes from interfering with the inflammatory process in the central nervous system.

- The drug has been approved in Switzerland since the end of 2020 as first-line therapy for adult patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS).

- Ozanimod is taken orally 1× daily and was well tolerated in the studies with no significant gastrointestinal side effects. These data are consistent with initial observations from clinical practice.

Literature:

- Scott FL, Clemons B, Brooks J, et al: Ozanimod (RPC1063) is a potent sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 (S1P1) and receptor-5 (S1P5) agonist with autoimmune disease-modifying activity. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(11): 1778-1792.

- Giovannoni G, Turner B, Gnanapavan S, et al: Is it time to target no evident disease activity (NEDA) in multiple sclerosis? Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015 Jul;4(4): 329-333. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2015.04.006. epub 2015 May 8. PMID: 26195051.

- Ziemssen T, Derfuss T, de Stefano N, et al: Optimizing treatment success in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2016 Jun;263(6): 1053-1065. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7986-y. Epub 2015 Dec 24. PMID: 26705122; PMCID: PMC4893374.

- Kappos L, De Stefano N, Freedman MS, et al: Inclusion of brain volume loss in a revised measure of “no evidence of disease activity” (NEDA-4) in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2016

- Cohen JA, Comi G, Selmaj KW; RADIANCE Trial Investigators, et al: Safety and efficacy of ozanimod versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RADIANCE): a multicentre, randomised, 24-month, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019

- Comi G, Kappos L, Selmaj KW, SUNBEAM Study Investigators, et al: Safety and efficacy of ozanimod versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis (SUNBEAM): a multicentre, randomised, minimum 12-month, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019

- Cohen JA, Comi G, Arnold DL, RADIANCE Trial Investigators, et al: Efficacy and safety of ozanimod in multiple sclerosis: dose-blinded extension of a randomized phase II study. Mult Scler. 2019

- Drug Compendium of Switzerland, compendium.ch, as of 01/2021

- swissmedicinfo.ch, Status 01/2021

- Rocca MA, Battaglini M, Benedict RH, et al: Brain MRI atrophy quantification in MS: From methods to clinical application. Neurology. 2017

- Sastre-Garriga J, Pareto D, Battaglini M, et al: MAGNIMS consensus recommendations on the use of brain and spinal cord atrophy measures in clinical practice. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(3): 171-182.

- Robles-Diaz M, Lucena MI, Kaplowitz N, Spanish DILI Registry, et al: LatinDILI Network; Safer and Faster Evidence-based Translation Consortium. Use of Hy’s law and a new composite algorithm to predict acute liver failure in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2014 Jul;147(1): 109-118.e5.

- Evangelopoulos ME, Miclea A, Schrewe L, et al: Frequency and clinical characteristics of multiple sclerosis rebounds after withdrawal of fingolimod. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018 Oct;24(10): 984-986.

- Berger JR, Brandstadter R, Bar-Or A: COVID-19 and MS disease-modifying therapies. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020 May

- www.multiplesklerose.ch/de/aktuelles/detail/anti-sars-cov2-impfung-und-multiple-sklerose (retrieved 08.03.2021)

- www.msif.org/news/2020/02/10/the-coronavirus-and-ms-what-you-need-to-know (retrieved 08.03.2021)

- Spezialitätenliste Schweiz, Federal Office of Public Health, www.spezialitätenliste.ch/ShowPreparations.aspx (retrieved 08.03.2021)

- European medicines agency, ema.europa.eu (retrieved 08.03.2021).

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2021; 19(3): 12-18.