Anticoagulants increase the risk of bleeding but do not prevent strokes in patients with atrial high rate episodes (AHRE) and without ECG-diagnosed atrial fibrillation. This is the conclusion of the NOAH-AFNET-6 study presented by study leader Prof. Paulus Kirchhof in the first Hot Line Session at the ESC Congress 2023 [1,2].

Oral anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists [3] or direct-acting oral inhibitors of factor II or Xa2 (NOACs), which are not vitamin K antagonists, reduces the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Non-vitamin K antagonists are currently preferred to vitamin K antagonists because they are associated with a lower risk of bleeding [4,5]. Oral anticoagulant therapy is often only initiated in patients with atrial fibrillation after a stroke [6,7]. Systematic rhythm monitoring to detect atrial fibrillation can enable earlier detection of atrial fibrillation and the initiation of anticoagulant therapy [8,9]. Implanted heart devices enable continuous monitoring of the heart rhythm. With the help of intracardiac or subcutaneous sensors, they can record short episodes of atrial arrhythmias. Arrhythmias detected by this type of continuous rhythm monitoring are referred to as subclinical atrial fibrillation or atrial high rate episodes (AHREs). Because the electrical activity of the heart recorded during AHREs is similar to that in atrial fibrillation, some physicians have initiated oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with AHREs, particularly in patients with multiple clinical risk factors for stroke or in AHREs lasting longer than 24 hours [10]. Due to their rarity and episodic nature, AHREs usually go undetected in patients who do not undergo long-term rhythm monitoring [11].

In the absence of atrial fibrillation, oral anticoagulation has generally not been shown to be effective in preventing stroke in patients who have suffered an embolic stroke of unknown cause [12,13] or heart failure [14,15].

Efficacy and safety investigated for the first time

NOAH-AFNET 6 (Non vitamin K antagonist Oral anticoagulants in patients with Atrial High rate episodes trial) is the first study to investigate the efficacy and safety of oral anticoagulation in patients with AHRE and without ECG-documented atrial fibrillation. The randomized, double-blind study compared the NOAC (new oral anticoagulant) edoxaban with placebo in patients ≥65 years of age with AHRE episodes ≥6 minutes detected by implantable devices [16]. It is estimated that around 10 to 30% of patients with implanted devices have AHREs that last longer than five or six minutes [10]. In addition, patients had to have one or more of the following risk factors for a stroke: Heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack, vascular disease (previous myocardial infarction, aortic plaque or peripheral, carotid or cerebral artery disease) or age ≥75 years [16]. Exclusion criteria were atrial fibrillation as documented by ECG, acute coronary syndrome, percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary bypass surgery within 30 days prior to enrollment in the study, life expectancy of less than 12 months, contraindication to oral anticoagulation or edoxaban, indication for dual antiplatelet therapy and other indications for oral anticoagulation.

Eligible patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to edoxaban (anticoagulation) or placebo. Randomization took place in blocks of variable size and was stratified according to the indication for acetylsalicylic acid therapy.

Anticoagulation consisted of the factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban at the dose approved for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (60 mg once daily). The criteria for dose reduction to 30 mg once daily as approved by the European regulatory authorities (a body weight of ≤60 kg, creatinine clearance of 15 to 50 ml per minute or concomitant use of strong P-glycoprotein inhibitors) were reviewed at baseline and at each subsequent visit, and appropriate dose adjustments were made. The doses of edoxaban and placebo were administered in quantities that would probably be sufficient for six months. The placebo group received a double pseudo-placebo tablet containing either no active substance or acetylsalicylic acid at a dose of 100 mg daily; which tablet a patient received was determined based on the recognized indications for the use of acetylsalicylic acid, which included peripheral or coronary heart disease, previous myocardial infarction or previous stroke.

Primary and secondary endpoints

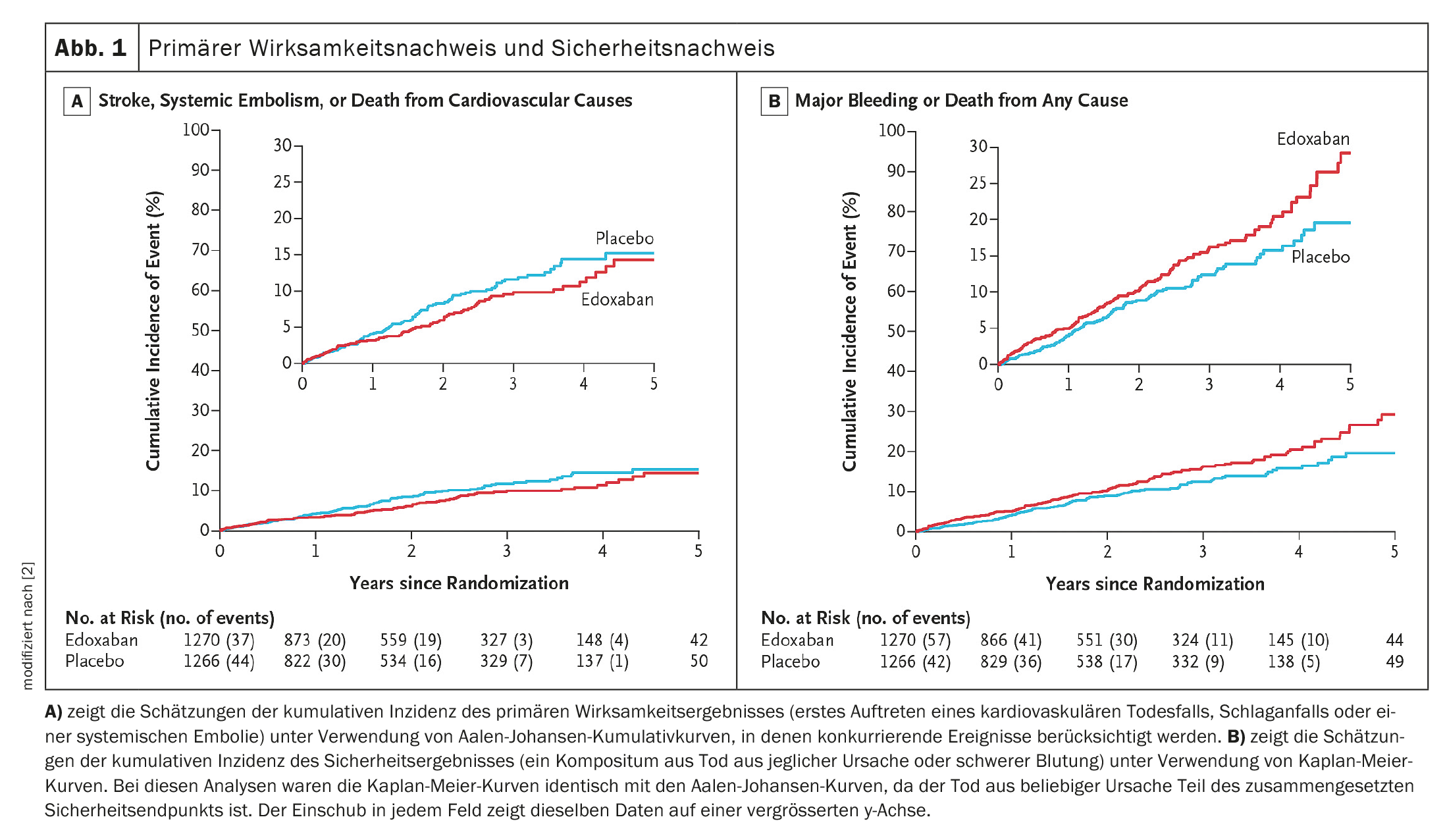

The primary efficacy endpoint was the first occurrence of composite cardiovascular death, stroke or systemic embolism, assessed in a time-to-event analysis [16]. The safety endpoint was composite death from any cause or major bleeding as defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis [16,17].

The main secondary endpoints were the individual components of the primary efficacy endpoint and the safety endpoint, a composite of stroke or systemic embolism, cognitive function as assessed by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, quality of life as assessed by the EuroQol Group 5-Dimension 5-Level Questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L), patient satisfaction and symptoms, assessed with the Perception of Anticoagulant Treatment Questionnaire, as well as the functional status, evaluated with the Karnofsky Performance Status Score [16].

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients at baseline

Between 2016 and 2022, a total of 2608 patients with AHREs were randomized at 206 sites in 18 European countries. The modified intention-to-treat population consisted of 2536 patients, including 1270 patients in the edoxaban group and 1266 patients in the placebo group. The average age of the patients was 78 years. The median duration of the AHREs was 2.8 hours, and the AHREs generally had atrial rates of more than 200 beats per minute. The median number of AHREs was 2.8 in each group. The median CHA2DS2-VASc score (which is used to predict the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation and ranges from 0 to 9, with higher scores indicating a higher risk of stroke) was four. The number of patients who discontinued the study before treatment with edoxaban or placebo and the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were similar in both groups.

Of the 1270 patients who received edoxaban, 365 (28.7%) met the criteria for a dose reduction to 30 mg once daily at the start of treatment. Edoxaban was discontinued after a median of 16.8 months. A total of 134 patients in the edoxaban group withdrew their consent, and atrial fibrillation occurred in 232 of 2674 patients. Of the 1266 patients in the placebo group, 683 (53.9%) received acetylsalicylic acid. Placebo was discontinued after a median of 16.7 months. A total of 134 patients in the placebo group withdrew their consent, and atrial fibrillation occurred in 230 of 2622 patients.

Study terminated prematurely: Safety concerns and ineffective anticoagulation

In September 2022, the study was terminated prematurely after a median follow-up period of 21 months due to safety concerns and the results of an informal assessment of the uselessness of the efficacy of edoxaban. At the time of study termination, planned enrollment was complete and 184 of the 220 planned primary efficacy events had occurred during a median follow-up of 21 months per patient in both groups (edoxaban group, 21 months; placebo group, 21 months).

A primary efficacy event occurred in 83 of 1270 patients in the edoxaban group and in 101 of 1266 patients in the placebo group (Fig. 1A) [2]. A safety event occurred in 149 of 1270 patients in the edoxaban group and in 114 of 1266 patients in the placebo group (Fig. 1B) [2]. The results of the sensitivity analyses of the primary efficacy outcome and the safety outcome, a subgroup analysis of the primary efficacy outcome and a per-protocol analysis of the primary efficacy outcome and the safety outcome, and the results of the analyses of the primary efficacy outcome and the safety outcome in the safety population (all patients who were randomized) were generally comparable to those of the analyses of the primary efficacy outcome and the safety outcome.

Stroke, systemic embolism or cardiovascular death as the primary efficacy outcome occurred in 83 people in the anticoagulation group (3.2%/year) and in 101 people in the group without anticoagulation (4.0%/year). There was no measurable difference in efficacy between the treatment groups – hazard ratio (HR): 0.81; 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 0.6-1.1; p=0.15. The stroke rate without anticoagulation was 1.1%/year and with anticoagulation 0.9%/year.

A major bleeding event or death of any kind as the primary safety outcome occurred in 149 participants in the anticoagulation group (5.9%/year) and in 114 in the group without anticoagulation (4.5%/year). This corresponds to an HR of 1.3 with 95% CI: 1.0-1.7; p=0.03. They account for the main difference in safety and occurred about twice as often as without anticoagulation – HR: 2.10; 95% CI: 1.30-3.38; p=0.002.

Patients with AHRE should be treated without anticoagulation!

In this randomized, double-blind, double-dummy study, oral anticoagulation with edoxaban at a dose approved for the treatment of atrial fibrillation did not result in a lower incidence of cardiovascular death, stroke or systemic embolism than without anticoagulation in patients with AHREs. However, edoxaban resulted in a higher incidence of the composite event of death from any cause or major bleeding. The incidence of events was generally within the expected ranges, with the exception of a low incidence of stroke in both study groups. Prof. Paulus Kirchhof, head of the study and clinic director at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), sees a need for further research: “Better methods for estimating the risk of stroke in patients with rare atrial arrhythmias are required.” Kirchhof also referred to the evaluation of wearables such as smartwatches with regard to rare atrial arrhythmias and atrial fibrillation as an interesting research approach [1].

Take-Home Messages

- In patients with atrial high rate episodes (AHRE) and clinical risk factors for stroke, anticoagulation with edoxaban at the dose approved for atrial fibrillation did not result in an overall reduction in stroke, systemic embolism or cardiovascular death. In the patient population analyzed, no subgroups that benefited could be identified.

- As expected, anticoagulation increased the risk of severe bleeding.

- The stroke rate was low with and without anticoagulation.

- Based on these results, patients with AHRE should be treated without anticoagulation until atrial fibrillation is diagnosed by ECG.

Congress: ESC 2023

Literature:

- Kirchhof P: Anticoagulation with edoxaban in patients with strial high-rate episodes (AHRE). Results of the NOAH – AFNET 6 Trial. Hot Line Session 1, ESC Congress 2023, Amsterdam, 25.08.2023.

- Kirchhof P, et al: Anticoagulation with edoxaban in patients with atrial high rate episodes. N Engl J Med 2023; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2303062.

- Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI: Metaanalysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 857-867.

- Ruff CT, et al: Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Lancet 2014; 383: 955-962.

- Hindricks G, et al: 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021; 42: 373-498.

- Grond M, et al: Improved detection of silent atrial fibrillation using 72-hour Holter ECG in patients with ischemic stroke: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Stroke 2013; 44: 3357-3364.

- Gladstone DJ, et al: Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2467-2477.

- Schnabel RB, et al: Early diagnosis and better rhythm management to improve outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: the 8th AFNET/EHRA consensus conference. Europace 2023; 25: 6-27.

- Freedman B, et al: Screening for atrial fibrillation: a report of the AF-SCREEN international collaboration. Circulation 2017; 135: 1851-1867.

- Toennis T, et al: The influence of atrial high-rate episodes on stroke and cardiovascular death: an update. Europace 2023; 25: euad166.

- Svendsen JH, et al: Implantable loop recorder detection of atrial fibrillation to prevent stroke (the LOOP study): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2021; 398: 1507-1516.

- Hart RG, et al: Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 2191-2201.

- Diener H-C, et al: Dabigatran for prevention of stroke after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 1906-1917.

- Zannad F, et al: Rivaroxaban in patients with heart failure, sinus rhythm, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 1332-1342.

- Homma S, et al: Warfarin and aspirin in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythm. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1859-1569.

- Kirchhof P, et al: Probing oral anticoagulation in patients with atrial high rate episodes: rationale and design of the non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial high rate episodes (NOAH-AFNET 6) trial. Am Heart J 2017; 190: 12-18.

- Schulman S, Kearon C, Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis: Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in nonsurgical patients. J Thromb Haemost 2005; 3: 692-624.

CARDIOVASC 2023; 22(4): 32-35 (published on 28.11.23, ahead of print)