The goals of early detection include preventing or delaying the transition to manifest disease and reducing preexisting symptoms or daily impairments. A risk for psychosis includes at least one attenuated psychotic symptom or at least two subjectively experienced cognitive symptoms or at least one transient psychotic symptom. A long duration of untreated psychosis has a negative impact on symptom development and everyday functioning. Proactive and cross-setting networking among providers is necessary for optimal treatment of patients with first episode psychosis.

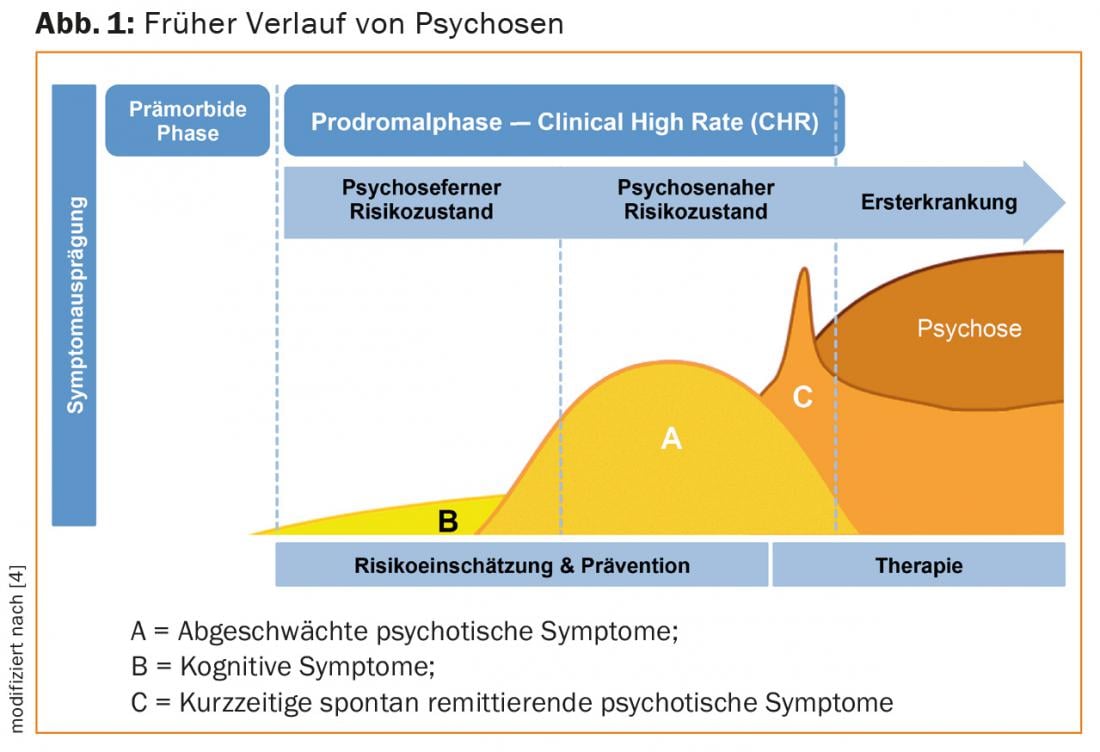

Psychoses are severe mental illnesses that are often associated with a persistent loss of quality of life and everyday function [1]. Initial psychosis usually occurs in early adulthood, when individuals are transitioning to independent living. In a majority of cases, less specific symptoms appear even before the onset of the first manifest psychosis (Fig. 1) . The symptoms manifest themselves individually, are often associated with distress and are often misinterpreted at the beginning as a reaction to stress or as a normal development during adolescence.

In the period shortly before and in the course of the first psychotic phase, decisive course can be set for the further development of the illness [2]. This is where the early detection of psychoses in the sense of secondary prevention comes in. It is aimed at people who are already burdened by symptoms and seek counseling and help because of them. The goals of early detection include preventing or delaying the transition to manifest disease and reducing preexisting symptoms or daily impairments.

Risk assessment

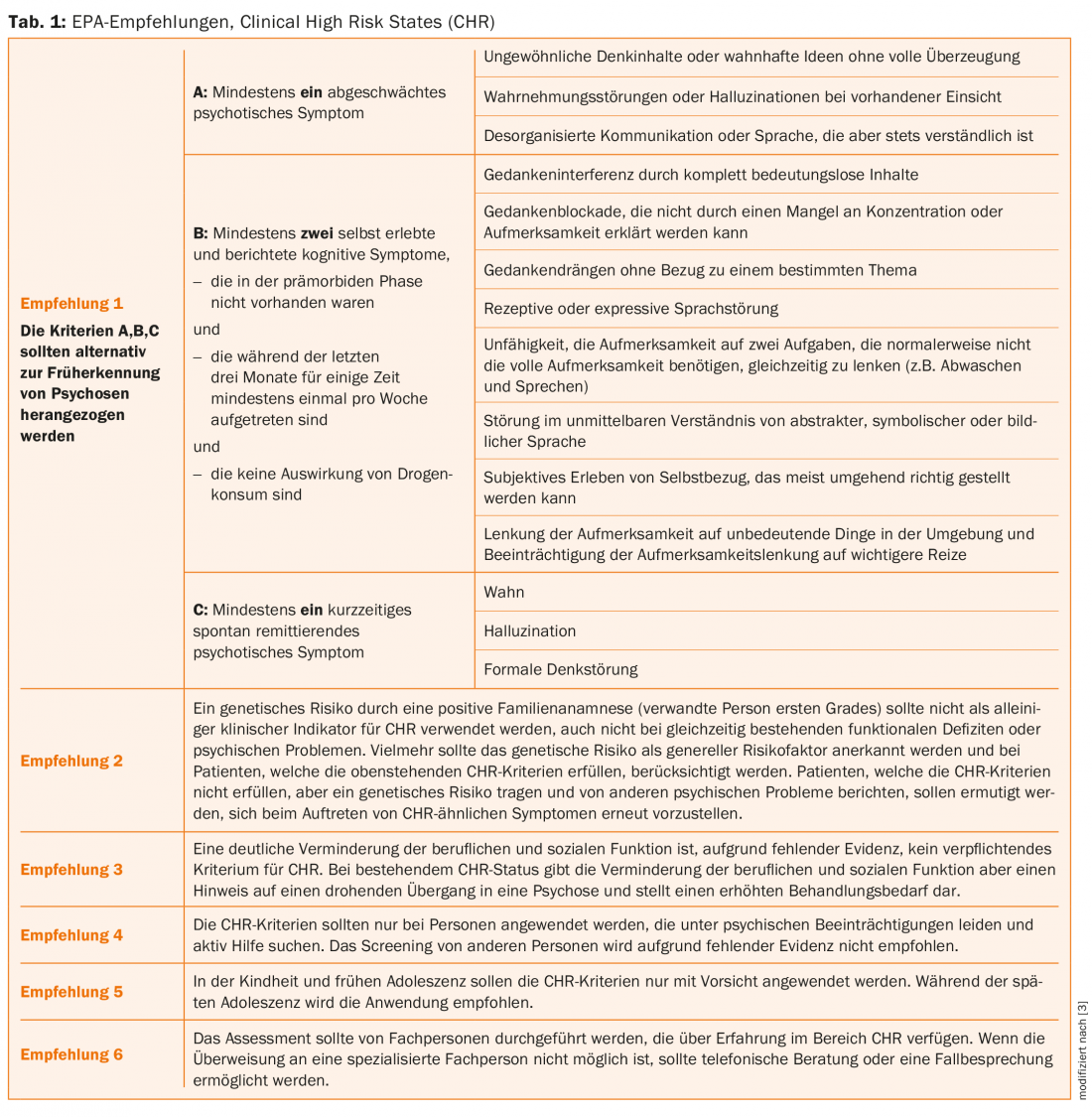

There are several approaches to assessing the risk of psychosis, known as the clinical high risk state (CHR). A review of existing assessment tools is provided in a recent meta-analysis [3]. The authors prepared six recommendations on behalf of the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) (Table 1).

If the risk criteria for psychosis are met, individuals are at up to 32% risk for transitioning to manifest psychosis within the next three years [4]. This means that about two-thirds of individuals in the at-risk state do not develop manifest psychosis within these three years. However, the individual studies showed a wide variation in transition rates. Interestingly, transition rates were lower in the more recent studies, which may be due to dilution effects (inclusion of lower-risk individuals) but may also be interpreted as an indication of successful treatment of high-risk individuals [4].

As the transition rates show, the presence of a risk state is not necessarily a prodromal symptom of psychosis. There is a large overlap with other diseases. About 40% of individuals at risk for psychotic illness simultaneously met diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode and about 15% for an anxiety disorder [5]. In the sense of the desired symptom reduction, other diseases should be treated in an appropriate way, e.g. by psychotherapy.

Prevention options

The current literature generally recommends a tiered approach for individuals in a state of risk, prioritizing the least restrictive measure in each case [6,7]. Supportive therapy focusing on individual needs should also consider comorbidities. If dependence problems exist at the same time, those affected should be motivated to achieve abstinence or at least a reduction in consumption. In addition, the use of cognitive therapy methods – with or without the involvement of the family – is evaluated as helpful. There are promising findings on dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids, which are currently being tested in clinical trials.

[6,7]Antipsychotic medication is not currently recommended as the first choice in the at-risk state because current studies show no advantage compared with other treatments that are less likely to cause side effects . In individual cases, however, the short-term use of antipsychotics can lead to a reduction in symptom burden even in the at-risk state. Drug treatment should always be carefully considered and should not be given simply because the criteria for psychosis risk are met. Long-term continuous medication of a preventive nature is not recommended [7].

An essential early intervention is the regular monitoring of mental status, so that in cases where the onset of a manifest illness cannot be prevented, appropriate treatment can be initiated without delay. This is particularly important because prolonged duration of untreated psychosis has a negative impact on further symptom development and everyday functioning [2].

First psychotic episode

In the case of manifest psychotic illness, treatment is indicated as soon as possible. One focus is on comprehensive diagnostics as well as comprehensible and accurate information. With regard to treatment goals, the focus today is no longer on symptom control and relapse prophylaxis alone, but on “recovery” in the sense of everyday function and subjective quality of life. The core concept of “empowerment”, i.e. the promotion of the affected person’s control and influence over psychiatric services and over his or her own life, as well as the inclusion of the individual’s explanatory model for the illness, must be understood as cornerstones of treatment. This is accompanied by the development of integrated therapeutic approaches that place great emphasis on psychotherapeutic, psychosocial, and rehabilitative procedures in addition to antipsychotic treatment.

Drug treatment as early as possible

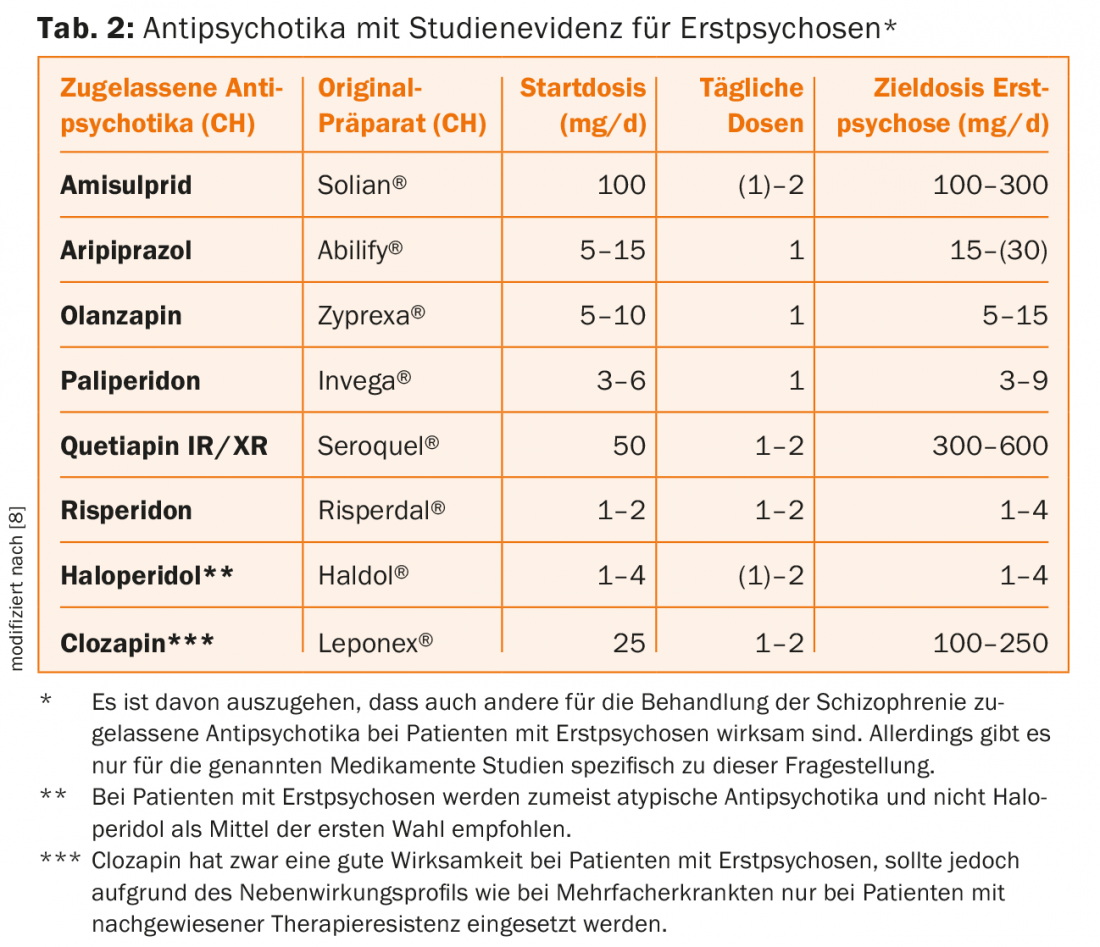

Regarding pharmacotherapy, there is consensus that antipsychotic therapy should begin as early as possible in manifest psychosis. Special features in first-time sufferers include higher response rates even at low doses, but also increased susceptibility to side effects. No uniform position is taken by the different international guidelines with regard to the preference for atypical over typical antipsychotics, with atypicals being preferred in Switzerland. Efficacy differences appear to be less pronounced than originally thought [6]. Typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause extrapyramidal motor side effects, whereas atypical antipsychotics are more likely to cause weight gain. At the same time, it must be noted that atypical antipsychotics represent a heterogeneous group of drugs. If possible, studies conducted specifically in first-episode patients should be considered (Table 2) [8].

Psychosocial interventions

Psychosocial interventions for patients with initial manifestations of psychosis include very different approaches [6,9]. An essential element is psychoeducation, the goals of which include developing an individual concept of the illness, promoting treatment commitment, dealing with the effects of the illness, and ultimately developing a positive outlook on life despite the illness. Psychoeducation is offered in very different forms and settings, although here a group format offers advantages in working through the issues together.

Another effective pillar is the work with relatives. There are very different approaches here, from providing information to working on intra-family communication to long-term family support. There is currently good to very good evidence for work with relatives. However, selecting specific interventions within these approaches is challenging in the day-to-day and individual patient setting.

In addition to psychoeducation and work with relatives, there is now good evidence for psychotherapeutic interventions in the narrower sense, although almost exclusively approaches based on cognitive behavioral therapy have been studied. In addition to form and setting, the studies conducted differ in their goals, which include relapse prevention, management of persistent symptoms, improvement of daily functioning, and coping with the experience of psychosis. The majority of these studies have been conducted in individual settings, but some have been conducted in group settings, and typically involve 16-20 hours.

With the increasing focus on patients’ everyday function, rehabilitative procedures are gaining importance. It must be noted here that only a few empirical studies exist to date for the group of first-episode patients with psychoses. An exception is the Supported Employment approach, where patients are accompanied by a job coach in their direct search for work in the primary labor market and then in the workplace [10]. In Switzerland, there are numerous other offers of occupational and everyday rehabilitation, which are profitably used in practice. Here, further empirical evaluation in relation to first-time patients would be desirable in order to select specific offers in a more targeted manner.

Networking

Overall, the field of early diagnosis and treatment of psychoses shows a dynamic development, which raises justified hope that our patients will have less burdensome restrictions due to the consequences of these disorders in the future. However, this rapid development in diagnostics and treatment also presents a new challenge that is difficult for the individual players in the healthcare system to overcome. Networking is also essential to reduce the very high proportion (more than 40%) of patients with first-episode psychosis who break off all contact with the health care system within a year. Optimal care of patients in this critical phase thus requires active networking of service providers to exploit synergies and optimize interfaces in care.

Literature:

- Mueser KT, et al: Schizophrenia. Lancet 2004; 363(9426): 2063-2072.

- Perkins DO, et al: Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162(10): 1785-1804.

- Schultze-Lutter F, et al: EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry 2015; 30(3): 405-416.

- Fusar-Poli P, et al: Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012a; 69(3): 220-229.

- Fusar-Poli P, et al: Comorbid Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in 509 Individuals with an At-Risk Mental State: Impact on Psychopathology and Transition to Psychosis. Schizophr Bull 2012b; doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs136.

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management 2014, http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG178/NICEGuidance/pdf/English.

- Schmidt SJ, et al: EPA guidance of the early intervention in clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry 2015; 30(3): 388-404.

- Hasan A, et al: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry 2012; 13: 318-378.

- Mueser KT, et al: Psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2013; 9: 465-497.

- Killackey E, et al: Vocational intervention in first-episode psychosis: individual placement and support v. treatment as usual. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 193(2): 114-120.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(4): 18-22.