Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is one of the most common gynecological diseases and affects millions of women worldwide, especially those of reproductive age. It is estimated that around 75% of all women will experience at least one episode of VVC in their lifetime, with 40 to 50% experiencing repeated episodes. About 5% of women experience recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC), which is defined as at least four episodes per year. This recurring form of the disease poses a particular challenge, as it is often difficult to treat and significantly impairs the quality of life of the women affected .

(red) In the vast majority of cases (85-90%), vulvovaginal candidiasis is caused by the yeast Candida albicans, which is present as part of the natural vaginal flora under normal conditions. However, various external and internal influences such as hormonal fluctuations, antibiotic therapy or a weakened immune system can lead to an overgrowth of the fungus, resulting in typical symptoms such as itching, burning, pain and discharge. In other cases, the infection is caused by non-albicans Candida species(NAC) such as Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis or Candida krusei . These types of fungi tend to be more resistant to therapy and are more difficult to treat.

In view of the increasing development of resistance to standard antifungal agents such as fluconazole and the recurrent nature of the disease, phytotherapy, i.e. treatment with herbal agents, is increasingly becoming the focus of research. This article provides a detailed overview of the role of phytotherapy in the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The most important plants and their bioactive ingredients, which have shown promising results in clinical and preclinical studies, are presented.

Pathogenesis of vulvovaginal candidiasis

VVC occurs when the balance between the normal vaginal flora and the Candida fungi is disturbed, leading to excessive growth of the fungi. Under normal conditions, Candida albicans lives as a commensal organism in the vagina and poses no threat. However, if the vaginal environment changes, e.g. due to increased oestrogen levels, antibiotic use or immunosuppression, the fungus can multiply and cause the typical symptoms of the infection.

The pathogenesis of VVC is complex and is influenced by a variety of virulence factors of the fungus. These include the ability of Candida albicans to bind to the vaginal epithelium, form biofilms, produce hydrolytic enzymes and change from the yeast form to the filamentous form. This morphological change enables the fungus to penetrate deep into the vaginal tissue and trigger a strong immune response. Biofilms also provide the fungi with protection from immune defenses and antifungal drugs, which complicates treatment and can lead to recurrent infections.

Another key aspect of pathogenesis is the ability of Candida albicans to produce hydrolytic enzymes such as proteases, lipases and phospholipases, which damage the vaginal epithelium and facilitate the invasion of the fungus. These enzymes also contribute to the destruction of the cell membranes and the spread of the fungi, which increases the severity of the infection.

Diagnosis and challenges in standard treatment

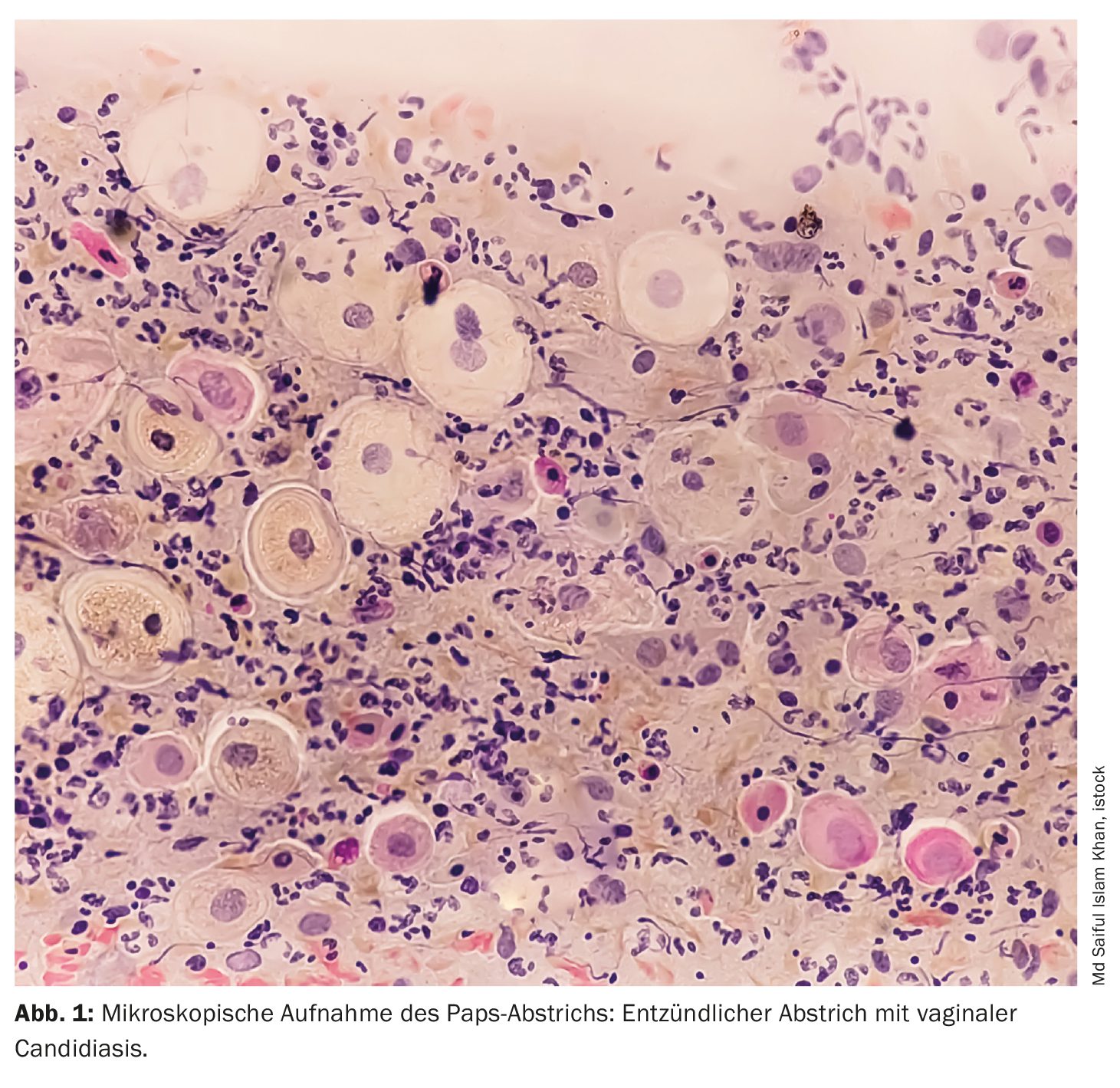

The diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis is based on a combination of clinical symptoms and microbiological tests. Usually, swabs are taken from the vagina and cultured in a laboratory to identify the fungus responsible. However, this approach has some limitations, particularly with non-albicans Candida species, which are often difficult to culture and respond poorly to standard antifungal agents.

The standard treatment for VVC is usually the administration of azole antifungals such as fluconazole or clotrimazole. These drugs work by inhibiting ergosterol biosynthesis, an important component of the fungal cell membrane. Despite their effectiveness in most cases, there are increasing reports of treatment failure, particularly in recurrent infections and in infections caused by non-albicans Candida species. In addition, azoles can cause a number of side effects, including headaches, nausea, skin rashes and, in rare cases, liver dysfunction.

Another problem is the increasing development of resistance to fluconazole, which is often used without medical supervision due to its wide availability. This has led to an increase in fluconazole-resistant Candida strains, particularly in patients with recurrent infections.

Phytotherapeutic approaches for vulvovaginal candidiasis

Given the increasing challenges in the treatment of VVC, phytotherapy is being investigated as a promising alternative to conventional antifungal drugs. Various plants and their bioactive compounds have been shown in vitro and in vivo to be effective against Candida while causing fewer side effects than synthetic drugs. Some of the most important plants and their potential applications in the treatment of VVC are presented below.

Garlic (Allium sativum): Garlic is a plant that has been known for centuries for its antimicrobial properties. The main active ingredient in garlic, allicin, has been shown to have a strong antifungal effect against Candida albicans. Allicin works by inhibiting the production of virulence factors that are responsible for the pathogenicity of Candida. In particular, allicin has been shown to significantly reduce the expression of the SIR2 gene, which is responsible for the morphological conversion of Candida from the yeast to the filamentous form. This prevents the spread of the fungus in the vaginal epithelium and can alleviate the symptoms of the infection.

In addition, allicin inhibits the formation of biofilms, which play an important role in the chronification of the infection. A clinical study has shown that garlic extract is similarly effective as fluconazole in the treatment of VVC, but causes fewer side effects.

Berberine (Berberis vulgaris): Berberine is an alkaloid found in various plants such as barberry (Berberis vulgaris) . It has strong antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties and is traditionally used to treat infections. Berberine works by inhibiting the adhesion of Candida cellsto the vaginal epithelium, which prevents the first step in the development of infection. Berberine also inhibits the formation of biofilms and reduces the expression of adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 and mucins, which are necessary for the fungus to bind to the epithelium.

A study has shown that berberine is effective in the treatment of Candida infections by inhibiting the transition phase of the fungus from the yeast form to the filamentous form. This reduces the invasiveness of the fungus and improves the chances of cure.

Turmeric (Curcuma longa): Turmeric is a popular spice known in traditional medicine for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. The main active ingredient, curcumin, has been shown in clinical studies to be effective against Candida infections. Curcumin inhibits the production of ergosterol in the cell membranes of Candida, which leads to destabilization of the membrane and ultimately to cell death.

A clinical study of 94 women showed that a 10% curcumin-based vaginal cream was as effective as a 1% clotrimazole cream in treating VVC. Curcumin was also found to cause fewer side effects and improve the cure rate in women with recurrent infections.

Dill (Anethum graveolens, Fig. 2): Dill is another plant used in traditional medicine. Studies have shown that dill oil has a strong antifungal effect against Candida by inhibiting ergosterol production and disrupting mitochondrial function in the fungal cells. This leads to a destabilization of the cell membranes and a reduction in ATP production, which ultimately leads to cell death.

In a clinical study of 60 women suffering from VVC, dill oil was found to have similar cure rates to clotrimazole, but caused fewer side effects. These results suggest that dill could be a promising alternative to conventional treatment of VVC.

Cannabidiol (CBD): Cannabidiol (CBD), an active ingredient from the hemp plant (Cannabis sativa), has attracted attention in recent years due to its versatile medical applications. In relation to VVC, CBD has been shown to inhibit the formation of biofilms and reduce the expression of genes responsible for Candida cell wall formation. In addition, CBD increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the fungal cells, which leads to their death.

Studies suggest that CBD could be an effective adjunct to standard therapy for VVC, particularly in patients who do not respond to conventional antifungal drugs or who experience recurrent infections.

The future of phytotherapy at VVC

Phytotherapy offers promising alternatives to conventional treatment of VVC, especially in cases where conventional antifungal drugs fail or lead to resistance. Although many of the studies conducted to date have shown promising results, further clinical trials are needed to confirm the efficacy and safety of these herbal therapies.

Another promising approach could be the combination of phytotherapy with conventional antimycotics. Initial studies suggest that herbal active ingredients such as curcumin and berberine could increase the efficacy of antifungal drugs and at the same time reduce their side effects. This could lead to new, combined therapeutic approaches that improve treatment outcomes in VVC.

Conclusion

Phytotherapy offers a promising alternative to the conventional treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Plants such as garlic, berberine, turmeric, dill and CBD have been shown in studies to be effective against Candida and cause fewer side effects than synthetic antifungals. Given the increasing challenges in the treatment of VVC, especially with recurrent infections and resistant Candida strains, phytotherapy could play an important role in the future. Further research is needed to establish these approaches in clinical practice, but the results so far are promising.

Source: Picheta N, Piekarz J, Burdan O, et al: Phytotherapy of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Mar 28;25(7): 3796.

doi: 10.3390/ijms25073796.

PMID: 38612606; PMCID: PMC11012191.

PHYTOTHERAPY PRACTICE 2024; 1(1): 30-31