Epileptic seizures are the clinical manifestation of excessive hypersynchronous discharges of neurons of the cerebral cortex. Although pharmacologic options have become much more diverse in recent decades, effective treatment management still presents significant challenges. The goal is individually designed precision medicine that optimizes the course of disease.

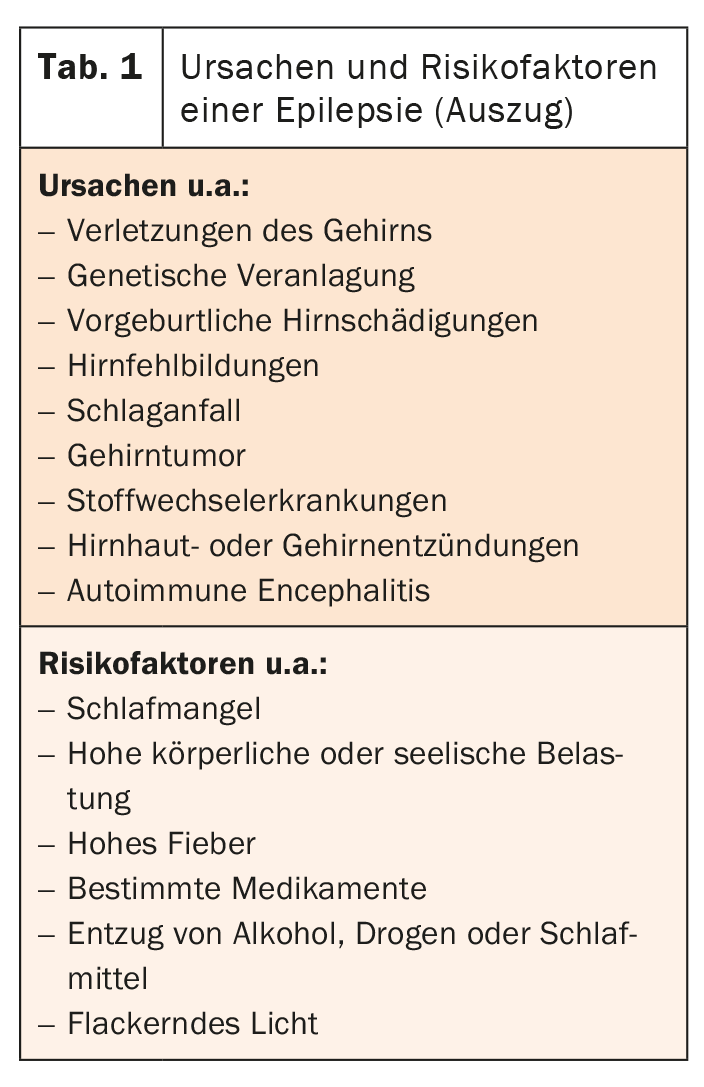

In Switzerland, about 80,000 people live with epilepsy [1]. Up to 5% of the population will experience an epileptic seizure in their lifetime [2]. Epilepsy is defined as a functional disorder of the brain that occurs due to pathological excitation formation in the absence of excitation limitation in the nerve cell assemblies of the CNS [3]. This requires at least two unprovoked epileptic seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart, or one unprovoked epileptic seizure associated with a high probability of further seizures occurring within the next 10 years. The causes and risk factors are complex (Table 1) [2]. In total, there are over 30 different types of epilepsy [1].

Several types of seizures are distinguished:

- Absence: Brief clouding of consciousness that usually occurs in childhood.

- Myoclonic seizure: seizure associated with twitching of individual muscle groups

- Focal seizure: Often altered perception (aura) in the run-up, then seizure limited to one area of the brain with, among other things, paraesthesia, automatic movements, speech disorders, etc.

- Generalized seizure: seizure in both cerebral hemispheres with unconsciousness and twitching or spasms of the extremities.

Furthermore, a seizure that initially starts focally may spread further and thus become a “secondary generalized seizure”. Whether a seizure recurs at all, if so, how often and how severe the condition is, varies greatly from individual to individual. The diagnostic procedure is therefore very comprehensive. In addition to a sequential description of the seizures by the patient, changes in the electroencephalogram (EEG) are detected. In addition to a surface EEG, an intracranial EEG may be required. Especially when an accurate diagnosis is a prerequisite for a successful surgical intervention. Multimodal imaging with high-field MRI or molecular imaging is then also used for this purpose [4].

Treatment options tailored to individual needs

Primarily, epilepsy is treated with antiepileptic drugs. In two-thirds of patients, long-term freedom from seizures can be achieved in this way. More than 20 different agents are available, including carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, valproic acid, and zonisamide. New developments in recent years for the treatment of focal epilepsies include eslicarbazepine acetate, perampanel, lacosamide, and brivaracetam. Eslicarbazepine acetate belongs to the third-generation antiepileptic drugs. As a further development of carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, it exhibits more selective use of the enantiomer and significantly improved pharmacokinetics. Thus, a single dose can also be given at more uniform serum levels. Only if the seizures persist despite medication do measures such as surgery, vagus nerve stimulation or deep brain stimulation take effect.

In principle, the choice of medication should be made individually. Therefore, in addition to the seizure situation, age, gender, and compliance should also be considered. Also, combination treatments are needed more often for difficult-to-treat epilepsies than for vascular epilepsies. In the latter, monotherapies with, for example, eslicarbazepine acetate, lamotrigine, or pregabalin are usually effective.

Literature:

- www.epi.ch/ueber-epilepsie (last accessed 07.03.2022)

- www.usz.ch/krankheit/epilepsie (last accessed 07.03.2022)

- https://flexikon.doccheck.com/de/Epilepsie (last accessed 07.03.2022)

- Baud MO, Schindler K, Flügel D, Bassetti C: Personalized chronotherapy in epilepsy. Swiss Med Forum. 2020; 20(3940): 532-537.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2022; 20(2): 32.