Introduction: The occurrence of dementia-like states in the context of depressive syndromes was already described in the last century with the terms “melancholic dementia”, “melancholia attonita” and “stupid depression” [1, 2].

Cognitive impairments of depressive disorders represent the main cause of reversible dementias [3] and show a high syndromal overlap and functional relationship with the cognitive disorders of primary dementing diseases [4, 5]. Especially in old age, a differential diagnostic differentiation of both diseases can be difficult [5]. In addition, there is a high comorbidity between depressive and dementia disorders [5].

Although additional testing may make the diagnosis of dementia or depression likely, even today definitive dementia- or depression-defining markers have not been established, and diagnosis finding remains primarily a clinical domain [5, 6]. Here, the time course or longitudinal assessment of cognitive abilities is particularly crucial [7].

In the present case, we present a patient with major depressive disorder with psychotic symptoms and prolonged cognitive deficits and, based on this, we would like to discuss differential diagnostic considerations.

Case Report

Anamnesis, clinical picture and therapeutic course: A 56-year-old businessman was referred to us at the beginning of June 2013 for ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) under the diagnoses “severe therapy-refractory depressive episode with psychotic symptoms” and “suspected disease from the extrapyramidal-motor group” from a neighboring psychiatric clinic.

Self and external history revealed that the patient was married, living with his wife, and had three adult children. Until mid-2012, the psychiatric history including substance history was unremarkable. On the somatics side, arterial hypertension treated with dual antihypertensive combination. There were no other vascular risk factors. Regarding the family history, it is worth mentioning that the patient’s father, who died some years ago, had suffered from Parkinson’s syndrome.

In mid-2012, the patient presented to his primary care physician because of excessive demands at work and associated anxiety. The latter initiated drug treatment with low-dose lorazepam. Due to the clear progression of the symptoms, which in some cases fluctuated considerably and consisted of concentration disorders, psychomotor restlessness, mutistic states, depressed affect, joylessness, hopelessness and inner restlessness, the patient was referred to a psychiatrist and psychotherapist in private practice in September 2012, who then attempted unsuccessful treatment with the antidepressant bupropion and the atypical neuroleptics olanzapine and aripiprazole.

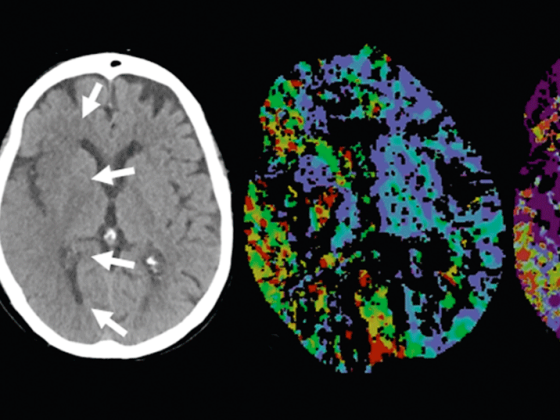

In early January 2013, he was admitted to the above-mentioned neighboring psychiatric hospital. Psychopathologically, the patient presented in a severely depressed state with massive drive reduction up to mutism as well as considerably dynamic, non-bizarre delusional symptoms of different themes (impairment, persecution, guilt) without the presence of sensory delusions or ego disorders. The laboratory chemistry diagnostics, including antineuronal antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, protein electrophoresis, thyroid antibodies, vitamins, folic acid, and vitamin B12, as well as Borrelia, HIV, and lues serology, were unremarkable. CSF status was regular with no evidence of intrathecal IgG or IgA synthesis or oligoclonal bands. Neuronal degeneration markers had not been determined. Cerebral MRI imaging revealed isolated, nonspecific medullary lesions of bifronto-occipital localization, which were most likely vascular in light of the known arterial hypertension. The EEG was normal. No response of the persistent major depressive psychotic state could be achieved under different antidepressant therapy regimens carried out in sufficient dosage and duration as well as in combination by means of the antidepressants sertraline, clomipramine and maprotiline (also as infusion therapy) as well as under mirror-controlled augmentation with lithium.

Because the patient exhibited myoclonia with the use of low-dose clozapine and developed a lateralized hypokinetic-rigid syndrome with the administration of the low-to-moderate-dose atypical neuroleptics olanzapine and risperidone, I-123-FP-CIT scintigraphy (DaTSCAN™) was performed as a complementary procedure, demonstrating a presynaptic dopaminergic deficit of the left striatum corresponding to the clinic. Against the background of the high sensitivity and specificity of this nuclear medical examination, this finding was considered a clear indication of an extrapyramidal disease or a neurodegenerative Parkinson’s syndrome that could not be further differentiated.

In early June 2013, under existing psychopharmacotherapy of clomipramine 50 mg/d, maprotiline 100 mg/d, lithium 24.4 mmol/d, and clozapine 25 mg/d, the patient was transferred to our clinic. Psychopathologically, there was a moderately severe reduction of attention, conception, and mnestic functions; a moderately slowed, circumstantial, and broodingly constricted formal thought process with perseverations; a severely impoverished and rigid affect with depressed and despairing mood; and a severe reduction of drive in the absence of delusional content-related thought disturbances, sensory delusions, and ego disturbances. Physical examination findings were unremarkable. In particular, no motor parkinsonian symptoms or other movement disorders were found.

With treatment resistance of major depressive episode with psychotic symptoms as defined [8], we performed electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) over eleven sessions for four weeks (until the end of June 2013) after switching psychopharmacotherapy to monotherapy with duloxetine 60 mg/d. This was done with bifrontal stimulation and two to three sessions per week.

Two weeks after the start of the ECT series, an incipient remission of the affective and psychomotor symptoms of the depressive syndrome was recorded, and after three weeks, a complete remission of the psychotic symptoms persisted.

Clinically, the focus was now increasingly on pronounced mnestic and other cognitive deficits relevant to everyday life, which had previously been assessed in the context of the dominant affective-psychotic symptomatology. Thereby, the patient showed a considerably reduced insight into the disease regarding the cognitive deficits with trivializing tendencies and self-overestimation. In the neuropsychological examination performed in mid-July 2013, two weeks after the last ECT session, the clinically unchanged persisting cognitive deficits could be objectified as clear deficits in verbal and figural memory functions, visuo-perceptual/visuo-constructive functions, and verbal and nonverbal executive functions (divided attention, verbal and nonverbal spontaneous flexibility, perseveration tendency, problems in categorization ability, problems in concept grasping and in concept and attention switching). A cerebral MRI performed again in early July 2013 for further diagnostic clarification showed numerous, small, partly confluent, subcortically and paraventricularly frontally accentuated, most likely microvascular medullary lesions. No inflammatory lesions or space-occupying processes were found, the width of the internal and external CSF spaces was regular, and MRA revealed the intracranial vessels to be regular. The neuro- and cardiovascular diagnostics including Doppler and duplex sonography of the extracranial brain-supplying vessels, transthoracic echocardiography, long-term ECG, clarification of vascular risk factors as well as determination of the immune-serological parameters ANA, ANCA, and rheumatoid factors, the results were unremarkable, except for the known arterial hypertension, which was adequately controlled by a dual combination, and evidence of associated hypertensive heart disease with mildly impaired LV function (EF 53%).

Differential diagnostic considerations

From our point of view, a definite etiological assignment of the stable cognitive deficits, which were clinically isolated even four weeks after the last ECT session, was not possible at that time.

Differentially, the following three causes were the main ones to be discussed.

Dementia and comorbid (organic) depressive disorder: applying the ICD-10 criteria of dementia to the patient, the required content criterion of decline in memory and decline in other cognitive functions was met in both clinical behavioral observation and quantification by neuropsychological testing. Likewise, the criterion of absence of disturbance of consciousness was given. A reduction in affect control and drive was clearly present during the course of the illness but remitted after ECT, with persistent coarsening of social behavior. The temporal criterion of six months’ duration was also fulfilled according to the inconsistency-free external and self-reported data as well as the retrospectively construed course of the disease with initial symptoms of very probably cognitively induced excessive demands at the workplace.

Against the background of the assumption of the presence of dementia, the depressive symptomatology remitted under ECT was to be evaluated as a comorbid organic affective disorder.

Regarding the etiology of dementia, from our point of view, Lewy body dementia (LKD) and vascular dementia were the most important to consider at this time.

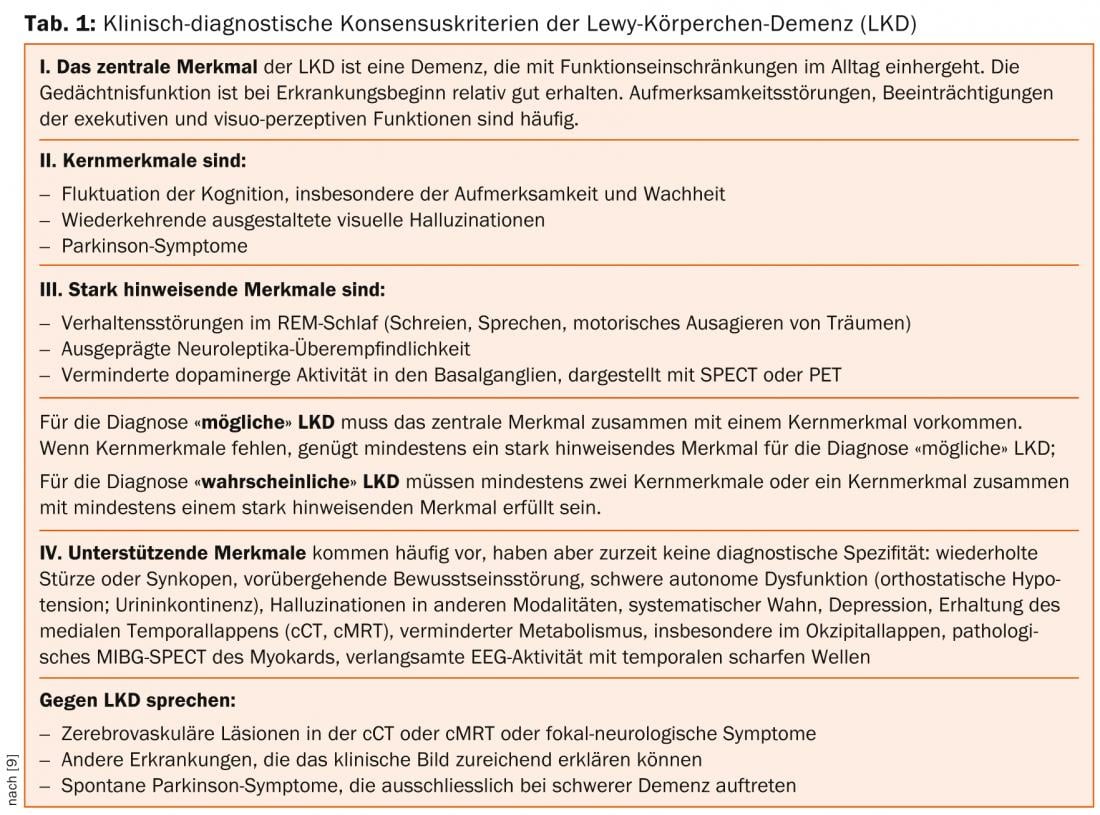

Considering the clinical diagnostic consensus criteria of LKD listed in Table 1 [9], if the two strongly suggestive features “marked neuroleptic hypersensitivity” and “decreased dopaminergic activity in the basal ganglia as visualized by SPECT or PET” were present, a possible LKD could be assumed. Also compatible with the diagnosis was the criterion of depression listed under supporting characteristics, as well as delusion. However, none of the core characteristics were met.

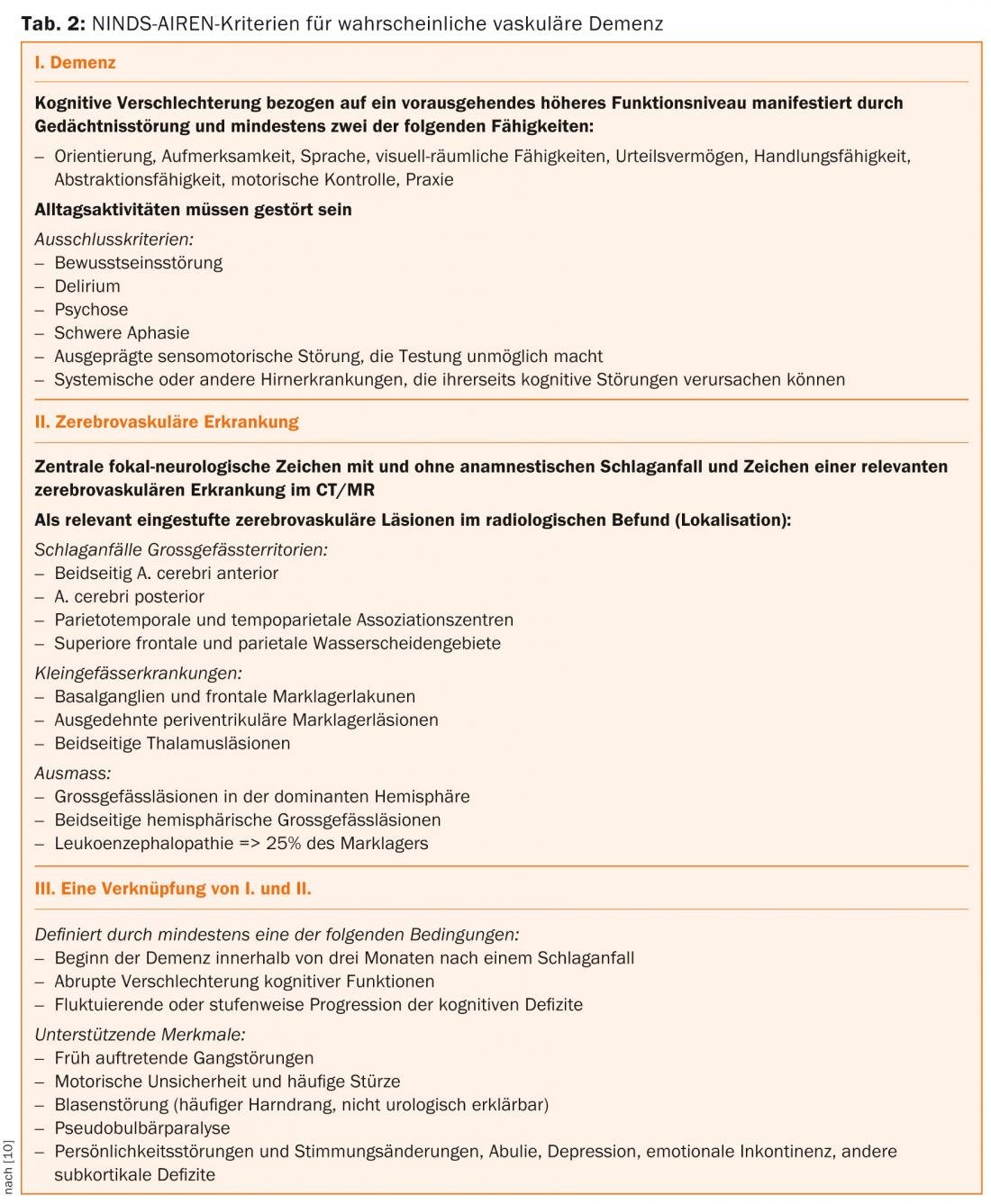

Applying the NINDS-AIREN criteria listed in Table 2. [10] of vascular or subcortical vascular dementia, imaging evidence of small vessel disease of the medullary canal of both hemispheres and evidence of arterial hypertension was present, but the quantitative criterion of leukencephalopathic changes => 25%) is not met, nor is the required uneven distribution of deficits in higher cognitive functions and evidence of focal brain damage.

Prolonged cognitive deficits in the context of depressive episode: as stated in the introduction, depressive syndromes are the main cause of reversible dementia [3]. The syndromic overlap of cognitive impairments of primary dementia and depressive disorders includes fatigue and reduced general performance, psychomotor slowing as well as agitation, impatience, restlessness, reduction of comprehension and concentration, formal thinking disorders such as inhibition, slowing of thinking with perseverations and adherence, limitation of critical faculties, orientation disorders to place and time, impairments in social behavior, and deficits of higher cortical functions such as abstraction and imagination, critical faculties, and judgment [5].

In our opinion, the view held by most authors that neuropsychological deficits in depressed patients correlate positively with the intensity of the depression and are greater the more effort or motivation and attention are required [3] was opposed to an explanation of the cognitive deficits (alone) by the depressive illness at this time, when the depressive, psychotic, and psychomotor symptoms had been stable and completely remitted for five weeks.

ECT side effects: Adverse effects of ECT were also to be discussed as a third potential explanation of the patient’s persistent, isolated, cognitive deficits. Adverse cognitive impairment occurs in approximately one-third of depressed ECT patients [5, 11]. Postictal deliriant syndromes with prolonged postictal orientation phase, disturbances of memory, and rare disturbances of attention, concentration, and executive functions are to be differentiated [5, 11]. Memory impairments primarily affecting episodic memory are divided into anterograde amnesia, retrograde amnesia, which primarily affects recent events, and negative effects on autobiographical and other long-term memory [5].

Arguing against the hypothesis of an ECT side effect was the pattern of cognitive deficits that was not dominated by mnestic deficits and the fact that ECT-induced cognitive deficits usually regressed completely two weeks after ECT and persisted for longer than four weeks in only 0.5% [5, 11, 12]. A return to baseline can be assumed after two weeks and further improvement thereafter [12]. It should be mentioned in general that retrograde, especially autobiographical, memory deficits may also persist longer and limit ECT [11].

Further course and diagnostic classification

After performing a maintenance ECT six weeks after the initial ECT series, we discharged the clinically unchanged patient from the inpatient setting in mid-August 2013 and recommended, in addition to continuation of antidepressant medication with duloxetine and another maintenance ECT in six weeks, further treatment including imaging and neuropsychological follow-up in an outpatient clinic affiliated with our hospital. Neuropsychological testing performed there at the end of August 2013 showed almost complete remission of cognitive deficits with persistent remission of depressive, psychotic, and psychomotor symptoms. The patient consistently achieved age-appropriate normal scores in the other tests evaluating attention, verbal and nonverbal memory, executive functions, language and language-associated functions, praxia, visual perception, and visuospatial processing, except for a mild impairment in divided attention and a moderate impairment in computer-based attention tasks. Compared to the first neuropsychological test, learning effects could almost be excluded, since other tests were used for the most part. The improvement in cognitive function was also reflected in self-reported and external history (outpatient psychiatrist, outpatient occupational and occupational therapists, and patient’s wife).

Based on this finding, which was confirmed in further clinical evaluations, the patient was retrospectively diagnosed with a major depressive episode with psychotic symptoms and prolonged cognitive deficits.

Conclusion for practice

There is a high comorbidity as well as a high syndromal overlap between cognitive deficits of primary dementing diseases and cognitive deficits in the context of depressive episodes, especially in elderly patients. A clear diagnostic classification is, as also underlined by our case report, often only possible in the temporal longitudinal course.

When evaluating the long-term course, it should be kept in mind that the presence of cognitive disorders in the context of depression that manifests itself for the first time in old age is to be considered a risk factor for dementia occurring in the further course [5]. We also consider this circumstance to be extremely relevant in our case, especially in light of the evidence of leukencephalopathic changes or the evidence of a loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. Whether and to what extent these changes were partly responsible for the prolonged persistence of cognitive symptoms in our patient must remain unclear. It is well known that vascular encephalopathic changes are found clustered in elderly depressed patients [3, 13]. These changes do not automatically prove the presence of a vascular dementia (component), but do imply increased vulnerability to depression in the presence of subcortical dysfunction [3, 14].

As our case report exemplarily shows, clinical parameters play a leading role in the diagnostic classification of the joint occurrence of depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits, which often can only be clarified in the course of time. This should be taken into account when evaluating and weighting individual so-called “objective” findings, such as findings of morphological or functional imaging.

The knowledge of the impossibility of a (too) early diagnostic determination should furthermore influence the communication with the patient and his relatives, the statements on prognosis and the planning of psycho- and socio-therapeutic or occupational rehabilitative measures.

Although the focus of the case report is on considerations of the differential diagnosis and course of major depressive episodes, we would like to emphasize in addition that in the present case remission of symptoms could only be achieved under ECT, and to point out that the use of ECT should be considered as a treatment alternative in severe, treatment-resistant depressive episodes [8].

Stefan Linder, MD

Prof. Dr. med. Heinz Böker

PD Stefan Kaiser, MD

Literature:

- Berrios GE: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985 May; 48(5): 393-400.

- Cummings JL: Adv Neurol 1983; 38: 165-183.

- Beyreuther K, et al. (Eds.): Dementias basics and clinic. Thieme Verlag 2002.

- Austin MP, et al: Br J Psychiatry 2001 Mar; 178: 200-206.

- Möller HJ, et al. (Eds.): Psychiatry, psychosomatics, psychotherapy. Volumes 1 and 2. Springer 2011.

- Stoppe G, Staedt J: Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 1993 May; 61 (5): 172-182.

- Ganguli M, et al: Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006 Feb; 63(2): 153-160.

- DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF, AkdÄ, BPtK, BApK, DAGSHG, DEGAM, DGPM, DGPs, DGRW (eds.) for the guideline group Unipolar Depression: S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression-Langfassung. 1st ed. 2009. DGPPN, ÄZQ, AWMF. Berlin, Düsseldorf 2009.

- McKeith IG, et al: Neurology 2005; 65: 1863-1872.

- Roman GC, et al: Neurology 1993; 43: 250-260.

- Baghai, et al. (Ed.): Electroconvulsive therapy. Springer 2004.

- Semkovska M, McLoughlin DM: Biol Psychiatry 2010 Sep 15; 68(6): 568-577.

- Stoppe G, et al: Fortschr Neurol Psychiatrie 1995; 63: 425-440.

- Krishnan KR: Ann Rev Med 1991; 42: 261-266.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2014; 12(2): 25-30.