Prosthetic infections are becoming more and more important due to an increasing number of primary prosthetics. The primary care physician is usually the first point of contact for patients when symptoms occur in the area of a prosthesis. In the case of infections of any foreign material in the body, the initiation of the correct diagnostic and therapeutic steps is time-critical, since the duration of the infection is decisive for the possible therapy or its success.

Prosthetic infections are becoming more and more important due to an increasing number of primary prosthetics. The primary care physician is usually the first point of contact for patients when symptoms occur in the area of a prosthesis. In the case of infections of any foreign material in the body, the initiation of the correct diagnostic and therapeutic steps is time-critical, since the duration of the infection is decisive for the possible therapy or its success. Therefore, a sound knowledge of the different types of infections and a rough overview of the therapies are important to ensure the primary care management of such patients.

Type of infection

Infections can arise either externally from surgery or injury, i.e., exogenously, or by hematogenous spread from another site of infection in the body. Therefore, when a prosthesis infection is suspected, it is always important to actively search for possible sources of infection and to exclude or confirm them with the appropriate diagnostic tools. Typical localizations for spreading foci of infection are lung, urinary bladder, gastrointestinal tract, and chronic foot ulcers. In addition, endocarditis or osteomyelitis (e.g. of the vertebral bodies) should also be considered. This list is not exhaustive, but includes those causes that can be ruled out by thorough clinical and instrumental examination. Knowing the type of infection (exogenous vs. hematogenous), along with the duration of the same, is an important factor for further treatment.

Duration of infection

In the first three months after implantation of a prosthesis, one speaks of an early infection, from 24 months after implantation of a late infection. In between there is an intermediate phase, which can only be reasonably classified and treated by considering the type of infection and the germ. Early infections tend to be exogenous (i.e., occurring during implantation) and late infections tend to be hematogenous.

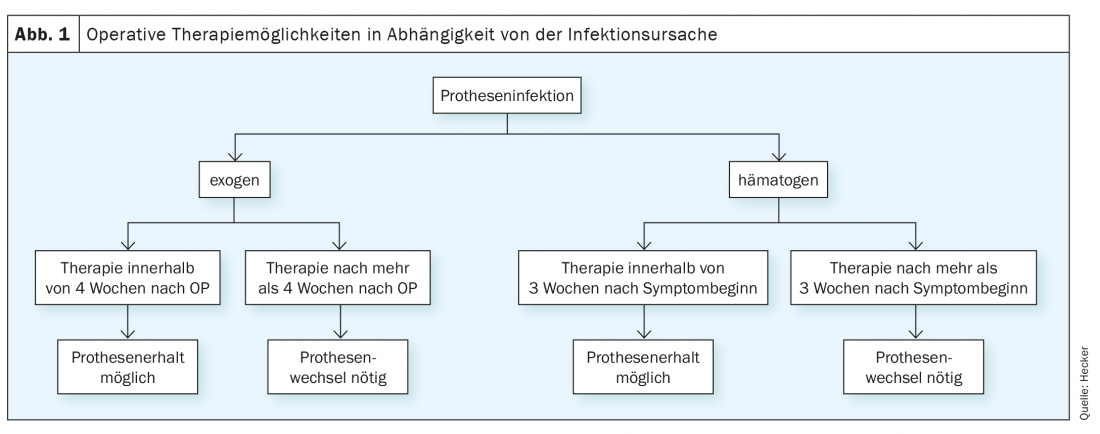

A further classification possibility into acute infection versus chronic infection is clearly more decisive for the therapy than the temporal relation to the index operation. Acute infections are designated as such if they either occur within 4 weeks of the index surgery or have been symptomatic for a maximum of 3 weeks at any time thereafter. All other cases of infection are treated as chronic. This classification is important in that prosthesis preservation is possible during this period. Thereafter, the failure rate of this procedure increases significantly, so that complete prosthesis replacement is usually recommended [1].

Affected joint

In order to primarily suspect a prosthesis infection, the initial examiner must be familiar with the different presentation of such an infection at the various joints. The knee and ankle often respond with significant swelling, redness and hyperthermia. The shoulder and hip, on the other hand, are less amenable to clinical assessment because there is also a larger soft tissue mantle. Here, the focus is usually on pain and, if necessary, a restriction of movement. However, so-called “low-grade” infections can occur at all joints, which initially usually present themselves clinically only very subtly [2].

Diagnostics

A thorough medical history and physical examination are the primary basis for diagnosis, but are unfortunately often neglected in favor of instrumental measures. The important systems to be investigated have already been listed above. At this point, however, it should be emphasized that small lesions should also be actively searched for as ports of entry, especially on the feet (sole of the foot, interdigital spaces between the toes). These are often not noticed by the patients themselves (e.g. due to reduced sensitivity). Subsequently, laboratory examinations (leukocytes, CRP, interleukin-6, blood count, urine status/culture) as well as radiological examinations of the corresponding joint and, if necessary, also of the lungs are indicated [3].

Elevated leukocyte count and CRP values may indicate infection, depending on the postoperative time point. However, normal values do not rule out infection. For example, in Proprionibacterium acnes infection, no elevated CRP can be detected in 75% and no elevation in leukocyte count in 93% of cases [4].

Many of the so-called low-grade germs behave similarly. The radiograph of the corresponding joint must be searched for signs of loosening, effusion or air pockets as indirect signs of infection. In addition, the differential diagnosis of a periprosthetic fracture can be excluded.

Joint puncture is now treated as the most important tool for diagnosing infection. Since this itself carries a risk of infection, it should only be performed if there is a reasonable suspicion of joint infection. Absolute sterility must be ensured here; a sterile drape, sterile gloves and, if possible, a small sterile table are strongly recommended for this purpose. Local anesthesia can lead to contamination of the puncture area and, if applied too deeply, to falsification of the culture results and should only be performed intracutaneously if absolutely necessary. To avoid contamination with skin germs, a stab incision using a pointed scalpel is recommended. The actual puncture is then performed deep through this already opened skin site. The punctate is examined by cell differentiation and count, microbiologically, and for crystals. Unfortunately, the sensitivity of shoulder puncture, for example, is rather poor at 33%, so that intraoperative samples become more important here. Hip and knee joint punctures have a much better sensitivity of about 90% [5,6].

Technically, this can certainly be performed by a general practitioner, but the puncture should rather be left to the surgeon who would also perform the surgical therapy, if necessary. This is mainly due to the fact that the latter can discuss the diagnostic possibilities with the responsible infectiologist on an interdisciplinary basis and can also directly assess the punctate macroscopically. These “side” observations, which are, however, partly important for the final procedure, are lost in the case of puncture by a general practitioner. In addition, there may be delays in the forwarding of findings.

Overall, with regard to diagnostics, it should be noted that in some cases with fulminant signs of infection and detected germ in the puncture, the diagnosis is simple and clear. Unfortunately, it happens at least as often that the diagnosis is difficult. This is the case, for example, when germs are not detected due to a dry puncture or in patients who have already received antibiotic treatment. In these cases in particular, it is important to consult a specialist with an interdisciplinary team as soon as possible in order to be able to make optimal use of all diagnostic measures.

Germ spectrum

This section does not deal explicitly with the individual pathogens, but rather aims to briefly raise awareness once again that there are basically two types of pathogens. The first group is easily recognized and draws attention with massive inflammation, elevated laboratory parameters, pus formation, fever, and eventual sepsis. In these cases, rapid action is required to avert what may be a vital threat to the patient.

The second group is more subtle, often “only” pain or swelling is a clinical symptom. Laboratory values may be normal and germ detection is difficult due to slow growth. Causes for this are mostly the mentioned “low-grade” germs or also fungi. Despite the primarily less fulminant course, such infections can also end in sepsis. In any case, they cause significant discomfort to patients. Here, rapid action is necessary above all to avoid a complete change of the prosthesis (which is associated with a significant risk of complications). Shoulder prostheses are particularly at risk here, since low-grade infections occur much more frequently in the shoulder region than in other joints [7].

Surgical therapy

In the case of a confirmed joint infection, surgical rehabilitation is the basis of therapy. There are different escalation levels, which can be selected depending on the duration of the infection, germ, soft tissue situation and comorbidities (Fig. 1).

Careful debridement with complete synovectomy and replacement of all mobile parts (especially polyethylene inlay). Also known as DAIR (debridement, antibiotics, implant retention), this method has a 30-100% success rate when performed for acute infections. In the case of chronic infections, most studies put the chances of success at less than 50%, so this procedure is then performed only in exceptional cases. In all cases that cannot be treated in the appropriate interval, a complete replacement of the prosthesis is indicated [8].

One-stage prosthesis exchange represents the next escalation stage and can be performed if the germ is known, the circulation and soft tissue situation are good, and there are few comorbidities. Compared to DAIR, however, this is a much more extensive procedure, as the removal of the prosthesis is usually time-consuming in the case of a fixed fit, and bone loss can also occur here. Such bone loss must be compensated for at great expense, and revision implants with a longer anchorage distance are often required for this purpose [9].

The safest option, which is recommended as the gold standard in case of doubt, is the two-stage prosthesis change. In this procedure, the prosthesis is first removed, thorough debridement is performed, and an antibiotic-loaded cement prosthesis is installed as a placeholder. Depending on the germ and soft tissue situation, a prosthesis is then reinstalled after a short (approx. 4 weeks) or long (approx. 3 months) interval. During this time, no load can be placed on the corresponding extremity, which represents a massive physical restriction and also psychological stress for the patient [10].

Other options, not discussed in detail here, include permanent removal of the joint (Girdlestone situation) and arthrodesis.

Antibiotic therapy

Each of the surgical therapies described above is successful only with subsequent antibiotic therapy. This should only be started in emergencies (septic patient) before the first surgical treatment, as this can make it difficult or impossible to detect germs. However, knowledge of the pathogen is crucial for the success of the therapy and must therefore be observed! If the germ is already known from a previous puncture, this rule can be deviated from after consultation with the infectiologists.

Following the first operation, the patient usually receives two weeks of intravenous antibiotic therapy, which is primarily started empirically if the germ is unknown and then changed accordingly in a targeted manner after the bacteriological results are obtained. The total duration of antibiotic therapy is usually between 3 and 6 months [10].

At this point, it must be explicitly pointed out once again that empirical antibiotic therapy initiated by a general practitioner is contraindicated in the event of a suspected prosthesis infection (e.g., also in the event of a wound healing disorder after implantation).

Case studies with possible errors in diagnostics and therapy

2 weeks after implantation of a KTP, the wound shows persistent secretion. Empirical oral antibiotic therapy is initiated, after which the wound closes. After 6 weeks, there is massive swelling and redness and severe pain. Pus is seen in the puncture.

–> It is an acute infection after implantation. If correctly diagnosed 2 weeks postoperatively, this could have been treated by surgical debridement and antibiotic therapy while preserving the prosthesis. Now, however, 6 weeks postoperatively, a complete change of the prosthesis is necessary. In addition, the therapy may be more difficult and a two-time change may be necessary, since the antibiotic treatment may not be able to detect the germs.

6 years after prosthesis implantation, a patient presents to his family physician and reports acute pain in the area of the prosthesis for 2 weeks. The general practitioner initiates a correct diagnosis by means of X-ray, laboratory examination and a puncture performed by himself. Laboratory and X-ray are unremarkable, the punctate shows an increased cell count, however, the practitioner still wants to wait for the culture result before initiating a referral. 10 days later, a low-grade germ appears in the culture, which presumably entered the system via an open site on the foot. Now the transfer takes place. 6 weeks after symptom onset, the patient finally presents to orthopedics.

–> In itself, the general practitioner has initiated a complete and correct diagnosis, only he has not taken into account the time factor. However, this means that prosthesis-preserving therapy, which would still have been promising in the first 3 weeks, can no longer be performed. Therefore, prosthesis replacement must now be performed at significant additional expense (both for the patient and socioeconomically).

Literature:

- Izakovicova P, Borens O, Trampuz A: Periprosthetic joint infection: current concepts and outlook. EFORT Open Rev 2019; 4: 482-494.

- Romano CL, Khawashki HA, Benzakour T, et al: The W.A.I.O.T. definition of high-grade and low-grade peri-prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Med 2019; 8: 650.

- Li C, Renz N, Trampuz A: Management of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Hip Pelvis 2018; 30: 138-146.

- Topolski MS, Chin PY, Sperling JW, et al: Revision shoulder arthroplasty with positive intraoperative cultures: the value of preoperative studies and intraoperative histology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006; 15: 402-406.

- Hecker A, Jungwirth-Weinberger A, Bauer MR, et al: The accuracy of joint aspiration for the diagnosis of shoulder infections. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2020; 29: 516-520.

- Yee DK, Chiu KY, Yan CH, et al: Review article: Joint aspiration for diagnosis of periprosthetic infection. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2013; 21: 236-240.

- Cooper ME, Trivedi NN, Sivasundaram L, et al: Diagnosis and Management of Periprosthetic Joint Infection After Shoulder Arthroplasty. JBJS Rev 2019; 7: e3.

- Di Benedetto P, Di Benedetto ED, Salviato D, et al: Acute periprosthetic knee infection: is there still a role for DAIR? Acta Biomed 2017; 88: 84-91.

- Pangaud C, Ollivier M, Argenson JN: Outcome of single-stage versus two-stage exchange for revision knee arthroplasty for chronic periprosthetic infection. EFORT Open Rev 2019; 4: 495-502.

- Kuzyk PR, Dhotar HS, Sternheim A, et al: Two-stage revision arthroplasty for management of chronic periprosthetic hip and knee infection: techniques, controversies, and outcomes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2014; 22: 153-164.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(2): 10-13