If adolescents are only able to cope with a low level of stress and have difficulty concentrating, a sleep medical assessment is indicated. Last but not least, good psychoeducation is important in the treatment of various sleep disorders.

Adequate and good quality sleep is essential for healthy development and learning capacity. However, sleep disorders already affect about 25% of children and adolescents. The most common symptoms are fatigue, daytime exhaustion, difficulty concentrating, irritability and low resilience. It is not uncommon for these to be secondary or comorbid to developmental disorders and thus present a differential diagnostic challenge. In addition to the consequences of such disorders for the children themselves, sleep disorders in childhood and adolescence also trigger subjective and physiologically measurable stress in parents [1]. Frequently, family physicians or pediatricians are confronted with this problem as the first point of contact. Therefore, in this article we want to give an overview of the most common sleep disorders in these age groups and present useful initial diagnostic steps and treatment options.

Insomnia

Symptoms: Insomniac symptoms manifest themselves in the form of difficulty falling asleep or sleeping through the night or early waking; in infants, they may manifest as crying disorders. According to the current guidelines, such symptoms on >3 days per week for >3 months are a chronic form [2]. In addition to being stressed at night, affected individuals are also tired and unfocused during the day, which is often misdiagnosed as a putative attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [3]. In fact, children with ADHD also show prolonged sleep onset latencies and altered sleep architecture compared to healthy controls [4].

Sleep disorders can also be caused by poor sleep hygiene. A review of 36 studies showed an association between general media use (TV, computer, electronic games, Internet, smartphones) and delayed bedtime and shorter total sleep duration [5]. A survey of 390 12- to 20-year-olds confirmed the link between smartphone ownership and later bedtimes. Electronic media use in bed before falling asleep correlated negatively with sleep length and positively with depression symptoms and sleep difficulties [6].

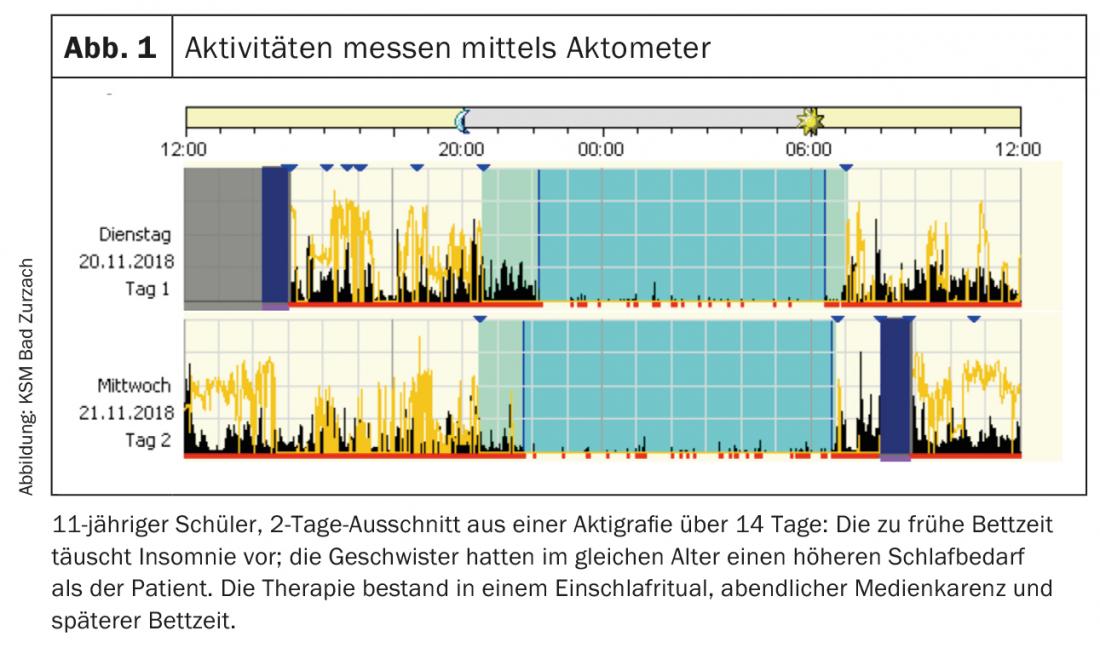

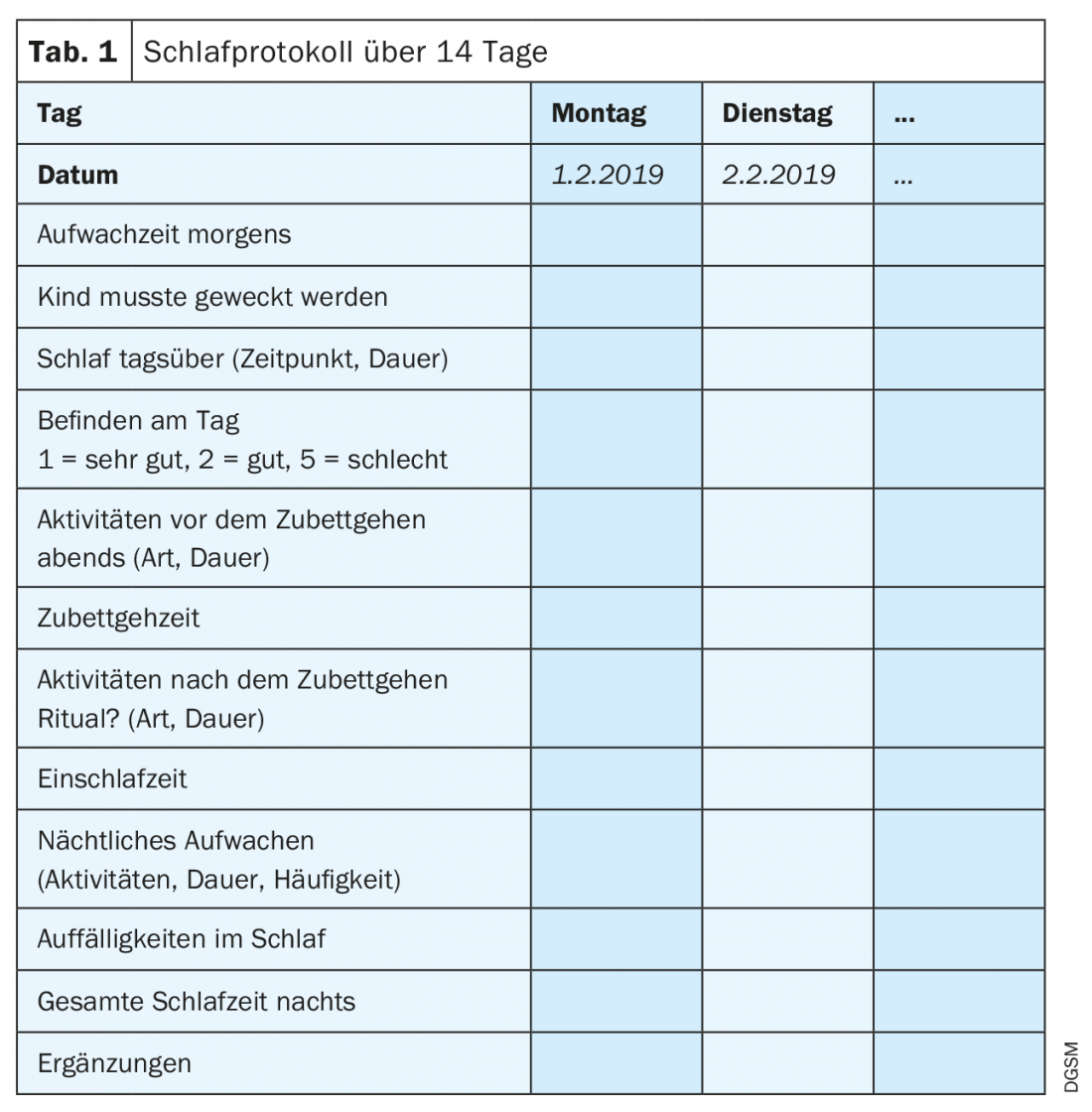

Diagnosis: Diagnostically, questionnaires such as the Sleep Self-Report (German version: SSR-DE 7-12) can be used. It is also useful to document sleep behavior in detail in a sleep log that is kept over 14 days (child, support by parents) (tab. 1). In addition, a movement meter (actometer) can record activity and light exposure over 24 hours (Fig. 1). The precise recording of sleep and wakefulness behavior provides starting points for therapeutic options.

Occasionally, parents overestimate a child’s need for sleep, thereby establishing incorrect sleep habits. Differential diagnosis must include anxiety disorders or affective disorders [7].

Treatment: Therapeutically, various measures of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) are available [8]. These include stimulus control (getting up and engaging in a quiet, pleasant activity as soon as one feels uncomfortable in bed), limited and regular bedtimes and daily routines, relaxation procedures, and cognitive techniques (mentalizing procedures). In addition, sleep hygiene measures are taught (box), which also provide guidance for supporting rhythm throughout the day [10].

Parasomnia

Symptoms: The term parasomnia is derived from the fact that these symptoms occur alongside sleep and do not necessarily affect the quality and restfulness of sleep. Parasomnias are distinguished between those that occur during REM sleep and those that arise from NREM sleep. The latter include sleepwalking, talking in one’s sleep, Pavor nocturnus, and nightmares. NREM parasomnias are arousal disorders that have a prevalence of up to 40% in children before preschool age. Frequently, the disorders remit in late adolescence [11]. Based on their presumed mechanism, they occur more frequently in the first half of the night, which consists proportionately of more NREM sleep. Another parasomnia that predominantly affects children is enuresis (bedwetting). While this still occurs in 43% of children at the age of three, the incidence is reduced to 20% in four-year-olds and 1-2% in adolescents.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is usually based on history of others or video recordings of episodes. Differentially, nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy must be considered. Here, there are specific features in polysomnography (PSG) that are diagnostically crucial.

Treatment: Central to treatment is psychoeducation and relief for parents and children. In most cases, no medication needs to be used. It is important to secure the environment to protect the child from injury. Further, reinforcing factors such as sleep deprivation and stress should be avoided as much as possible, and the causes of nocturnal arousal should be treated. For very high levels of distress, risk of injury, or special occasions, clonazepam may be used off-label for a limited time [12].

For enuresis, operant conditioning through positive reinforcement and calmness helps more than punishment [13]. Bedwetting children should be asked about symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing (snoring, pauses in breathing, restless sleep) [14].

Circadian rhythm disturbances

Symptoms: While parasomniac symptoms often fade in school-age children and adolescents, conflicts with the internal clock become more frequent in adolescence. In addition to chronobiological changes (sleep pressure builds up more slowly in older adolescents than in younger children, maturation processes in the circadian system) [15], changes in the psychosocial milieu of teenagers also play a role (growing independence, opportunities and obligations, media consumption). An irregular sleep-wake rhythm or a delayed or advanced sleep phase syndrome can massively impair daytime well-being. Patients frequently complain of problems falling asleep or morning fatigue, often accompanied by tardiness at school. The prevalence in adolescents is high at 7-16%.

Diagnosis: In addition to an accurate medical history, the use of a sleep protocol for at least 14 days is recommended (tab. 1) . In addition, questionnaires can be used to record the chronotype (download at www.dgsm.de) [16]. Furthermore, melatonin production in saliva can be recorded to obtain a picture of the individual sleep-wake rhythm [17].

Treatment: A combined treatment of elements of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) and rhythm shifting is recommended. Rhythm shifting takes place by means of establishing regular bedtimes, exposure to light in the morning (daylight or medical light lamp), exercise during the day, and timed melatonin input when needed (off-label therapy) [18].

More sleep disorders

In this issue, Prof. Johannes Mathis provides information on narcolepsy, the leading symptom of which is chronic daytime sleepiness lasting more than three months. The evaluation takes place in a sleep laboratory with PSG and a sleep latency test during the day.

Obstructive sleep apnea (snoring, pauses in breathing, sweating, restless sleep) occurs in 1-2% of children. Symptoms include daytime sleepiness, declining school performance, and behavioral problems [19]. Polygraphy is recommended as a screening procedure (8-lead home measurement); oximetry is inaccurate, especially in children. For definitive clarification, a sleep video-polysomnography is recommended (sleep laboratory examination).

Movement disorders are expressed in infancy by myoclonia, and in preschool by rhythmic head bobbing, rocking, or teeth grinding (bruxism). Provided that no injuries occur, the symptoms are harmless and usually end spontaneously by the age of four. Bruxism may be related to stress or anxiety as well as tooth growth (deciduous and second teeth).

Take-Home Messages

- In case of concentration difficulties and low resilience, a sleep medical clarification should be considered in addition to developmental disorders.

- When treating insomnia, it is important to consider the child’s individual sleep needs. In addition to regular bedtimes and bedtime rituals, attention should also be paid to media consumption.

- NREM parasomnias, such as sleepwalking and crying during sleep, are common in children and have a good prognosis. It is important to educate and secure the area. If injuries occur, a sleep laboratory examination is recommended.

- If adolescents report difficulty falling asleep and morning fatigue, a delayed sleep-wake cycle should also be considered.

- In the case of enuresis and snoring, obstructive sleep apnea should be ruled out in the sleep laboratory.

Literature:

- Brandhorst I, et al: The cortisol awakening response in mothers of young children with sleep problems. Effects of an internet-based treatment program (Mini-KiSS Online). Somnology 2017; 21(1): 53-66.

- AASM: International Classification of Sleep Disorders. Third Edition (ICSD-3). 2014.

- Kneifel G: Sleep disorders. Frequently – and clearly underestimated. Dtsch Arztebl International 2016; 15: 124-127.

- Virring A, et al: Disturbed sleep in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is not a question of psychiatric comorbidity or ADHD presentation. J Sleep Res 2016; 25(3): 333-340.

- Cain N, Gradisar M: Electronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents. A review. Sleep Med 2010; 11(8): 735-742.

- Lemola S, et al: Adolescents’ electronic media use at night, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms in the smartphone age. J Youth Adolesc 2015; 44(2): 405-418.

- Brown WJ, et al: A review of sleep disturbance in children and adolescents with anxiety. J Sleep Res 2018; 27(3): e12635.

- Åslund L, et al: Cognitive and Behavioral Interventions to Improve Sleep in School-Age Children and Adolescents. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Sleep Med 2018; 14(11): 1937-1947.

- Halal CSE, Nunes ML: Education in children’s sleep hygiene: which approaches are effective? A systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2014; 90(5): 449-456.

- Kerzel S, et al: Building bridges – pediatric sleep medicine connects. Current Child Sleep Medicine 2017. Dresden: kleanthes Verlag für Medizin und Prävention, 2017.

- Jenni O, Benz C: Sleep disorders. Pediatrics up2date 2007; 2: 309-333.

- Kotagal S: Treatment of Dyssomnias and Parasomnias in Childhood. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2012; 14(6): 630-649.

- Sinha R, Raut S: Management of nocturnal enuresis. Myths and facts. World J Nephrol 2016; 5(4): 328-338.

- Zaffanello M, et al: Obstructive sleep-disordered breathing, enuresis and combined disorders in children: chance or related association? Swiss medical weekly 2017; 147: w14400.

- Carskadon MA, et al: Adolescent Sleep Patterns, Circadian Timing, and Sleepiness at a Transition to Early School Days. Sleep 1998; 21(8): 871-881.

- Werner H, et al: Assessment of Chronotype in Four- to Eleven-Year-Old Children: Reliability and Validity of the Children’s Chronotype Questionnaire (CCTQ). Chronobiol Int 2009; 26(5): 992-1014.

- Pandi-Perumal SR, et al: Dim light melatonin onset (DLMO): a tool for the analysis of circadian phase in human sleep and chronobiological disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2007; 31(1): 1-11.

- Kirchhoff F, et al: Use of melatonin in children with sleep disorders: Statement of the Pediatrics Working Group of the German Sleep Research and Sleep Medicine Society (DGSM). In: Erler T, Paditz E, eds: Time Age Sleep: Current Child Sleep Medicine 2018. Dresden: kleanthes Verlag für Medizin und Prävention, 2018: 68-82.

- Hunter SJ, et al: Effect of Sleep-disordered Breathing Severity on Cognitive Performance Measures in a Large Community Cohort of Young School-aged Children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194(6): 739-747.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2019; 14(3): 8-10