The updated German-language guideline for the treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) is based on the EuroGuiDerm guideline and has been expanded to include some important new features. Since AD is a chronic inflammatory disease with a frequently recurrent course and adequate treatment requires a certain degree of adherence to therapy, information and instruction for patients is of great importance.

“It is important to explain the pathomechanisms to patients so that they understand the meaning and purpose of therapeutic measures,” says Prof. Dr. med. Dagmar Simon, Head Physician, Department of Dermatology, Inselspital Bern [1]. Depending on the age of the children concerned, it is important to involve the parents/caregivers. The two pathomechanisms primarily relevant to the treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) are the barrier defect and type 2 inflammation. “Atopic dermatitis is still a clinical diagnosis,” stated Prof. Simon [1]. The long-established classification criteria of Hanifin and Rajka or the criteria of the UK Working Party are still authoritative [4,5]. The clinical manifestations of AD are recurrent eczematous skin lesions, xeroderma, erythema, lichenification and scaling. Excoriations and also weeping lesions. The skin symptoms can vary greatly from person to person and can be differently pronounced depending on the stage and age. While the face is often affected in infancy, the skin lesions spread to the extremities and trunk area as they progress. In toddlers and preschool children, eczema often develops in the bends of the knees, elbows and neck, but also on the neck, face (especially the eyelids), back of the feet and hands. In adulthood, the face and neck are the main areas affected, in addition to the large bends of the joints [1].

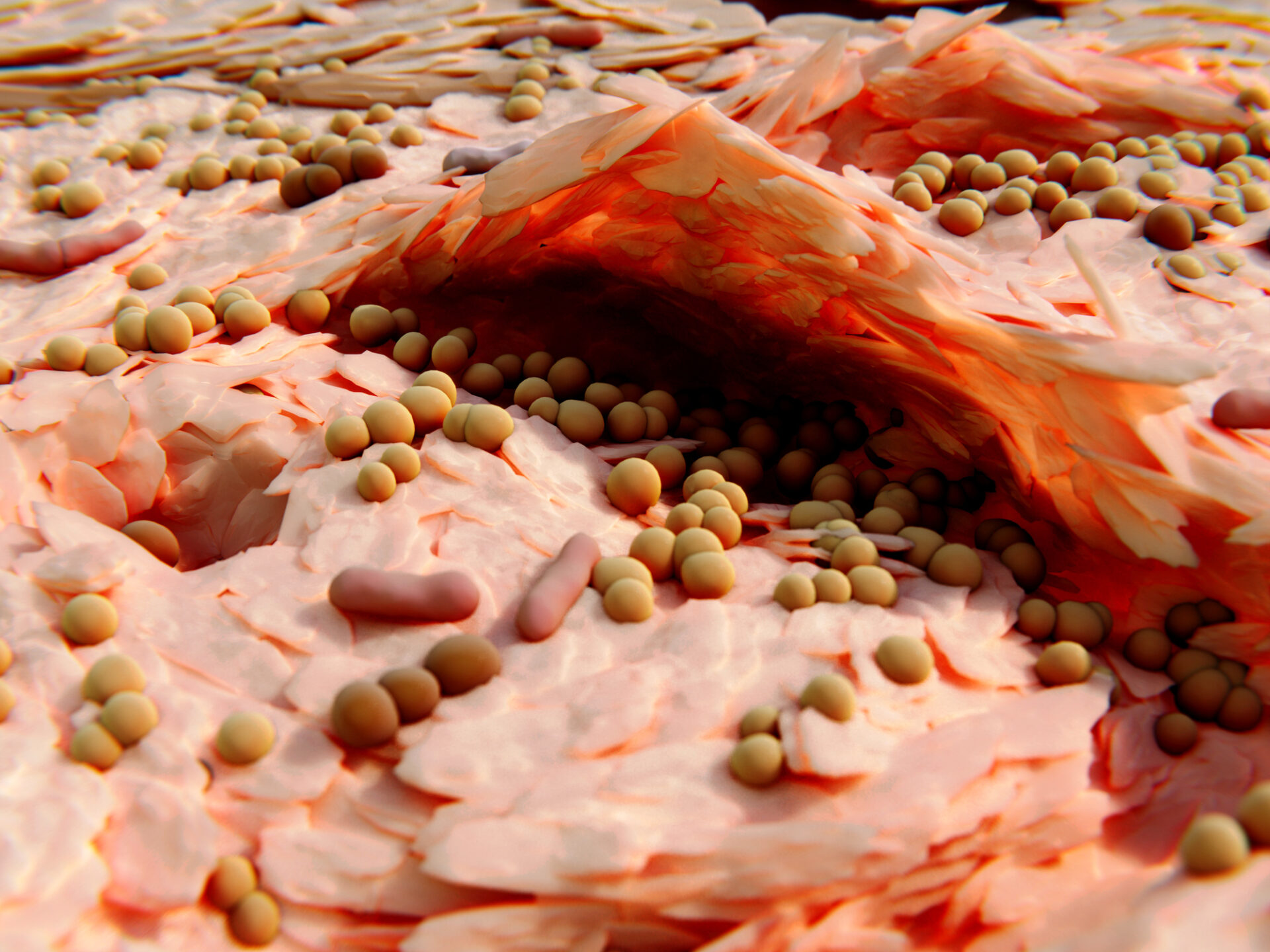

Type 2-dominated immune response and itch-scratch circle

The pathophysiology of AD is characterized by a complex orchestrated interplay of genetic factors, barrier defects, a type 2

dominated immune response and environmental influences [6]. Immune dysregulation is primarily based on T helper 2 cells (Th2)

and the cytokines they produce, in particular interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13. The Th2 reaction is associated with increased IgE levels and eosinophilic immune responses [7]. In addition, Th2 cytokines further strengthen the skin barrier, which is already impaired in AD, which can favor the penetration of irritants, among other things. Studies show that the skin microbiota contributes to the regulation of immune responses [8]. An increased incidence of Staphylococcus aureus correlates with the severity of AD [9]. TSLP in turn can stimulate sensory neurons involved in the induction of itching [10]. This can form a feedback loop in which mechanical damage caused by scratching induces an upregulation of TSLP expression [11]. “Itching is an important leading symptom in AD,” emphasized the speaker [1]. The pruritus symptoms can lead to sleep disturbances. In addition, patients with AD often suffer from atopic comorbidities [2,3].

Risk of “atopic march”

By definition, atopy is a hypersensitivity of the skin and mucous membranes to environmental factors or everyday mechanical, chemical and immunological influences [12–14]. In most cases, AD precedes other atopic diseases. In addition to allergic rhinitis/rhinoconjunctivitis and bronchial asthma, the latter often include immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated food allergies and eosinophilic esophagitis [12–14]. Patients with pediatric AD (“early-onset” AD) are particularly at risk of an “atopic march”. The exact mechanisms that lead to the development of atopic comorbidities in AD patients have not yet been fully clarified. However, it is now known that many of the T cell subpopulations and cytokines involved in the pathophysiology of AD also play an important role in other atopic diseases [15–17]. In this respect, skin inflammation may contribute to systemic allergic sensitization at [18,19].

Treatment according to step-by-step scheme

The treatment of AD must be individually adapted to the age, course of the disease, localization of the lesions and the patient’s level of suffering [20]. It is recommended to carry out a step therapy adapted to the clinical severity. It is also advisable to avoid individual trigger factors [20,21]. “Patient education is really important,” emphasized Prof. Simon [1]. It has been shown that adherence can be improved through treatment plans and patient-oriented instruction.

Basic care: In addition to avoiding provocation factors and relevant allergens, the basic treatment of AD consists primarily of the regular application of moisturizing and lipid-replenishing topical external agents containing glycerine or urea, for example [20]. Emollients should always be applied, especially after showering or bathing. “Basic therapy is very important – even if patients are receiving systemic therapy, emollients should be applied regularly,” the speaker explained [1].

Topical anti-inflammatory therapy: Topical corticosteroids (TCS) are the first choice for mild to moderate eczema. Prof. Simon recommends the use of class II TCS (e.g. methylprednisolone, prednicarbate) or class III (e.g. mometasone) [1]. Initially at a frequency of 1× daily and when the symptoms have improved, either proceed according to the tapering scheme (1× every second day, 1× every third day) or proceed directly to maintenance therapy (2×/week). TCS lead to a faster onset of action compared to topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI). TCS are therefore considered first-line therapy for acute exacerbations. However, TCS should be used for a limited period of time or as interval therapy to avoid skin atrophy as a possible side effect [20]. TCI (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) can be used second-line as a topical alternative. In sensitive regions, TCI may be preferable to TCS. The recommended frequency of application for TCI is initially 2×/day. As part of a proactive maintenance therapy, the treatment can then be switched to 2×/week as with TCS. “Topical therapy is sufficient for most patients, but systemic therapy should be considered in more severe cases,” said the speaker [1].

Light therapy: According to the guideline, treatment with phototherapy (UVA-1, UVB narrowband) can be considered for patients >18 years of age with moderate or severe AD lesions in acute phases of the disease.

Systemic treatment: If the eczema cannot be adequately treated with topical therapies/light therapy, the use of systemic therapeutics should be considered [20]. In Switzerland, the use of a conventional systemic therapeutic agent is required before treatment with biologics or JAK inhibitors (JAK-i) can be transferred to the health insurance fund.

- Conventional systemic therapeutics: Ciclosporin is the most frequently used representative of this group of drugs [20,22]. Azathioprine and methotrexate are used less frequently. According to the guideline, conventional immunosuppressants should only be used as short-term or interval therapy and after weighing up the possible risks of side effects.

- Biologics: Two monoclonal antibodies are currently available for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Dupilumab (Dupixent®) has been approved in Switzerland since 2019 [22,23]. Accordingly, there is already a great deal of experience with this immunomodulatory agent. Dupilumab binds the IL-4 receptor subunit alpha (IL-4Rα), thereby blocking the receptor binding of IL-4 and IL-13 [24,25]. The biologic is generally very well tolerated and can now also be used for adolescents and children (from 6 months) [22]. The most common side effects are local reactions at the injection site and conjunctivitis. The speaker points out that these can usually be treated well with eye drops; if necessary, a referral to an ophthalmologist should be considered [1]. Tralokinumab (Adtralza®), which was approved in Switzerland in 2022, is another biologic available for the AD indication [22,23]. The good efficacy and safety of tralokinumab has now also been confirmed in the long term. While this biologic can also be used for adolescents in the EU, official approval in Switzerland is currently limited to AD patients over the age of 18 (status of information 04.03.2024) [22,23].

- JAK inhibitors: JAK-i inhibit the intracellular signal transduction of proinflammatory cytokines with varying selectivity and thus prevent the signal transduction of various upstream receptors. The first representative of the JAK-i class approved for AD was baricitinib (Olumiant®) [22]. This was later followed by the approval of upadacitinib (Rinvoq®) and abrocitinib (Cibinqo®) [22]. All three substances inhibit JAK-1 and baricitinib also inhibits JAK-2. To date, JAK-i has only been approved for adult AD patients [22]. These are drugs with a very rapid onset of action, although the general safety profile of JAK-i is the subject of controversial debate. There is a consensus that certain precautionary measures must be observed. Particularly in patients with certain pre-existing conditions (e.g. cardiovascular disease) or risk factors (e.g. increased risk of venous thromboembolism) and in the over 65 age group, alternative therapies should be considered and chronic infectious diseases should be ruled out before starting therapy. However, it is also pointed out that the warnings in the information for healthcare professionals are based on study data in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and are only transferable to the AD indication to a limited extent. The complete screening and monitoring measures are described in detail in the guideline [20].

Congress: Allergy & Immunology Update

Literature:

- “Managing atopic dermatitis: with focus in adolescents”, Symposium III: Th2 driven inflammation, Prof. Dr. med. D. Simon, Allergy & Immunology Update, 26-28.01.2024.

- Werfel T, et al: Guideline neurodermatitis [atopic eczema; atopic dermatitis], 2016, S2k, AWMF register number: 013-027.

- Deckert S, Kopkow C, Schmitt J: Nonallergic comorbidities of atopic eczema: an overview of systematic reviews. Allergy 2014; 69(1): 37-45.

- Hanifin JM, Rajka G: Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta dermato venereological 1980: 44-70.

- Williams HC, et al: The U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis. I. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 1994; 131(3): 383-396.

- Traidl S, Werfel T, Traidl-Hoffmann C: Atopic Eczema: Pathophysiological findings as the beginning of a new era of therapeutic options. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2021. doi: 10.1007/164_2021_492.

- Berger A: Th1 and Th2 responses: what are they? BMJ 2000; 321: 424.

- Yamazaki Y, Nakamura Y, Núñez G: Role of the microbiota in skin immunity and atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int 2017; 66: 539-544.

- Nakatsuji T, et al: Staphylococcus aureus exploits epidermal barrier defects in atopic dermatitis to trigger cytokine expression. J Invest Dermatol 2016; 136: 2192-2200.

- Wilson SR, et al: The epithelial cell-derived atopic dermatitis cytokine TSLP activates neurons to induce itch. Cell 2013; 155: 285-295.

- Oyoshi MK, et al: Mechanical injury polarizes skin dendritic cells to elicit a TH2 response by inducing cutaneous thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126: 976-984.e5.

- Paller AS, et al: The atopic march and atopic multimorbidity: many trajectories, many pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;143: 46-55.

- Johansson SG, et al: Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: report of the nomenclature review committee of the world allergy organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 832-836.

- Buhl T, Werfel T: [Atopische Dermatitis – Perspektiven und unerfüllte medizinische Bedarfe]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023; 21(4): 349-354.

- Wambre E, et al: A phenotypically and functionally distinct human TH2 cell subpopulation is associated with allergic disorders. Sci Transl Med 2017; 9: eaam9171.

- Cianferoni A, Spergel J: The importance of TSLP in allergic disease and its role as a potential therapeutic target. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2014; 10: 1463-1474.

- Qu N, et al: Pivotal roles of T-helper 17-related cytokines, IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23, in inflammatory diseases. Clin Dev Immunol 2013; 2013: 968549.

- Hill DA, Spergel JM: The atopic march: critical evidence and clinical relevance. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 120: 131-137.

- Brunner PM, et al: The blood proteomic signature of early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis shows systemic inflammation and is distinct from adult long-standing disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 81: 510-519.

- Werfel T, et al: S3 guideline “Atopic dermatitis”, 2023, AWMF registry no. 013-027 (as of: 16/06/2023), https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/013-027,(last accessed 04.03.2024).

- Akdis CA, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Report. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 118(1): 152-169.

- Swissmedic: Medicinal product information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch,(last accessed 04.03.2024)

- PharmaWiki, PharmaWiki, www.pharmawiki.ch,(last accessed 04.03.2024)

- McCormick SM, Heller NM: Commentary: IL-4 and IL-13 receptors and signaling. Cytokine 2015; 75(1):38-50.

- Hamilton JD, Ungar B, Guttman-Yassky E: Drug evaluation review: dupilumab in atopic dermatitis. Immunotherapy 2015q; 7(10):1043-58.

- Wollenberg A, et al: European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema: part I – systemic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36(9): 1409-1431.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2024; 34(2): 28-29 (published on 24.4.24, ahead of print)