Prevention of microvascular and macrovascular complications is an important overarching goal in the management of type 2 diabetes, and the current SGED guidelines have further informed decision making in cardiovascular outcome studies and other evidence.

Prof. Roger Lehmann, MD, Senior Physician at the Department of Endocrinology, Diabetology and Clinical Nutrition at the University Hospital Zurich gave an update on SGED recommendations for type 2 diabetes therapy at FOMF 2019 in Zurich [1]. Treatment should be primarily patient-centered and multimodal. Regarding HbA1c control and treatment, the overall goal is to prevent microvascular and macrovascular complications. Various criteria must be weighed against each other when choosing medications. Priorities tailored to individual conditions can have a significant influence on the course of events, as the speaker pointed out in his presentation.

Algorithm for guideline-compliant procedure

Step 1: Verify type 2 diagnosis and set individual HbA1c target: Correctly assessing whether a patient has a primary insulin-dependent form of diabetes (type 1) or from a form that is not primarily insulin-dependent (type 2) is diseased, is of high relevance, the speaker explains. In addition to a high HbA1c value, symptoms such as polyuria, polydipsia or unwanted weight loss can be indicative of primary insulin dependence. Type 1 diabetes as an initial diagnosis in older age is rarer, but it can occur in individual cases, he said.

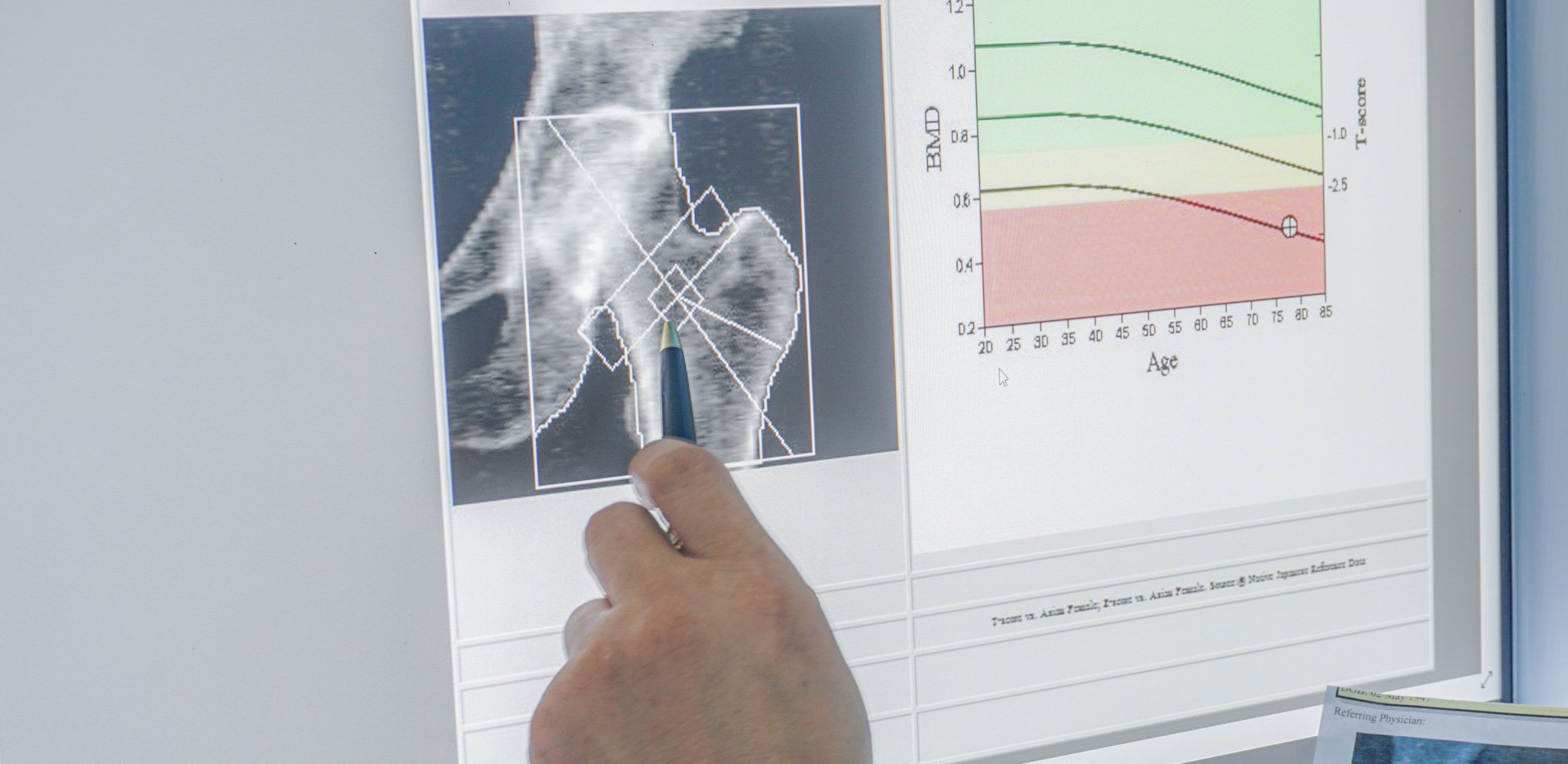

According to current SGED guidelines [2], the HbA1c target value should be set individually in the target range 6.0-8.0% (mostly <7.0%). If there is no risk of hypoglycemia, there is no lower HbA1c limit, which also applies to older type 2 diabetes patients. An HbA1c <of 6.5% is ideal, explains the speaker. In type 2 diabetes that is not primarily insulin-dependent, insulin treatment is indicated if HbA1c remains above 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) despite medication with oral antidiabetic agents or with an injectable GLP-1 analog, although a GLP-1 analog can also be combined with basal insulin treatment.

Step 2: Choice of therapy optimally adapted to individual conditions: One focus is on avoiding hypoglycemia and weight gain. Blood pressure control (systolic BP <140/90 mm Hg, diastolic BP >70 mm Hg), control of blood coagulation and, in overweight patients, lipid management (statin therapy, possibly in combination with Ezetrol) are further important target parameters that can be influenced by a combination of lifestyle factors (e.g., regular physical activity and healthy diet, smoking cessation) and a drug or therapy that is optimally tailored to individual conditions. a drug combination has proven to be appropriate [1].

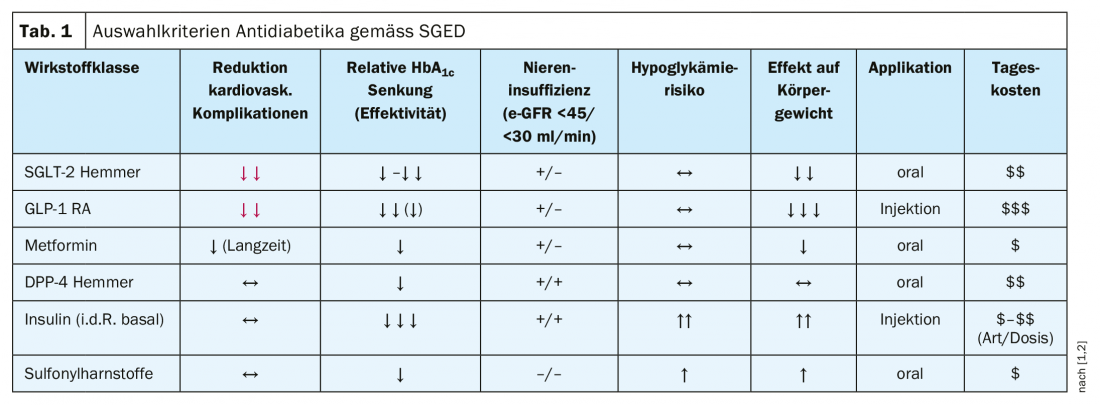

Step 3: Personalized choice of drug class/drug substance: There is now a broad evidence base for criteria-guided choice of appropriate antidiabetic drugs. In summary, according to current recommendations of the SGED, the following substance classes are to be preferred: SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists (RA), metformin, DPP-4 inhibitors [1]. It is important to set priorities, the speaker said. Specifically, this means that the following agents, among others, can be eliminated: Glitazones (induce obesity), alpha-glucosidase inhibitors (induce flatulence), glinides (used sparingly).

More difficult, however, is the choice of the individually optimal active ingredient or drug. of the respective combination of active ingredients. From cardiovascular endpoint studies, one has data on specific progression-related effects of various agents. The EMPA-REG endpoint study demonstrated that the SGLT-2 inhibitor empaglifozin (Jardiance®) led to significant reductions in the following outcome measures compared to placebo: 3-point MACE (Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events): 14%, cardiovascular mortality: 38%, heart failure hospitalization: 35%, all-cause mortality 32% [3]. CREDENCE is the latest endpoint study, according to which the SGLT-2 inhibitor canagliflozin achieved similar results [4]. Regarding GLP-1 RA, the LEADER endpoint study led to evidence of cardiovascular benefit of this class of compounds (3-point MACE: 13% reduction; cardiovascular mortality: 22% reduction; all-cause mortality: 15% reduction) [5].

Thus, both pharmacological groups lead to a reduction in cardiovascular mortality. There are no data yet on the effects of combined use of the two active ingredients. According to the speaker, however, the data available to date suggest that therapy with a combination of SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RA is best. However, the cost coverage by the health insurance is only guaranteed if the therapy is started with GLP-1 RA and then SGLT-2 inhibitors are added; in the reverse sequence, the costs are not covered, the speaker points out. There is still a great need for action in this regard.

Patient-centered priorities: evidence-based decision-making principles.

A focus is on avoiding micro- and macrovascular endpoints and in this context cardiovascular endpoints are given great relevance [1]. In addition, there are other criteria that can be taken into account in the selection of a suitable drug (Table 1) and whose weighting depends, among other things, on individual conditions:

- Therapy costs: The most cost-effective drugs are sulfonylureas and metformin.

- Avoidance of hypoglycemia: All of the following drug classes are suitable for this goal: Metformin, GLP-1 RA, SGLT-2 inhibitors, DPP-4 inhibitors. A “no go” is the combination of insulin and sulfonylureas, as this is associated with a high risk of hypoglycemia compared to other agents.

- Prevention of weight gain: evidence supports the suitability of the following medications (in descending order): GLP1>SGLT-2>metformin.

- Heart failure: SGLT-2 inhibitors (empaglifozin, canaglifozin, dapaglifozin) are superior: “With regard to heart failure, this is the best group of drugs available,” explains Prof. Lehmann.

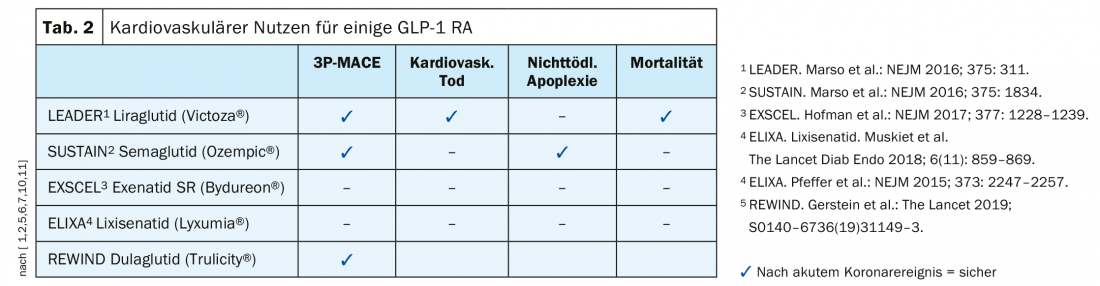

- Prevention of cardiovascular complications: Both SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RA are targetable. There are differences within the GLP-1 RA group (Table 2); according to endpoint studies, cardiovascular benefit was demonstrated for liraglutide (LEADER) [5], semaglutide [6], dulaglutide (REWIND) [7] (Box: REWIND: dulaglutide) , but not for exenatide-based drugs.

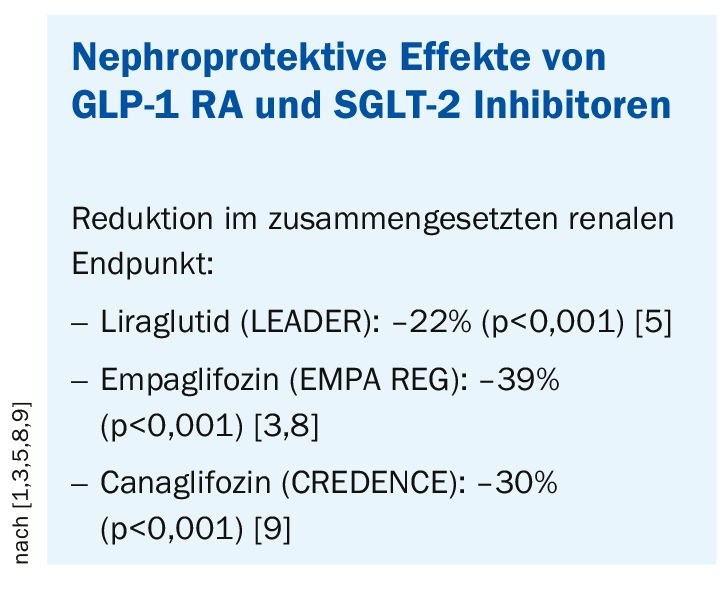

- Nephroprotection: both GLP-1 RA and SGLT-2 inhibitors protect the kidney (Box: Nephroprotective effects) [7].

Web-based app as a decision-making aid

As part of a dissertation project, a tool has been developed to support primary care physicians in making criteria-based therapy decisions, Prof. Lehmann reported. It is a project supported by the Swiss Society of Endocrinology and Diabetology (SGED). In summary, the use of this method enables a rapid update of new guideline recommendations. The system generates a therapy recommendation based on the input of the following basic data: type of diabetes, duration of diabetes; weight and age; chronic renal failure (eGFR <60 ml/min, <45 ml/min, <30 ml/min); cardiovascular disease: yes or no; heart failure: yes or no. In addition, it is indicated whether cost coverage by the health insurance is guaranteed [1].

Source: FomF AIM 2019, Zurich

Literature:

- FOMF: Prof. Roger Lehman, MD, Chief Physician at the Department of Endocrinology, Diabetology and Clinical Nutrition at the University Hospital Zurich, slide presentation: Current Guidelines for Oral Diabetes Therapy. General Internal Medicine Update Refresher, Zurich, May 22, 2019.

- Swiss Society of Endocrinology and Diabetology (SGED): Measures for Blood Glucose Control in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2

www.sgedssed.ch/fileadmin/files/6_empfehlungen_fachpersonen/61_richtlinien_fachaerzte/1703_SGED_Empfehlung_BZ-Kontrolle_T2DM_Finale_Version_13.pdf, last accessed 01 July 2019. - Zinman B, et al: Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2117-2128.

- Neal B, et al: Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. NEJM 2017; 377: 644-657.

- Marso SP, et al: LEADER Trial: liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 311-322. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603827.

- Marso SP, et al: Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. NEJM 2016; 375: 1834-1844.

- Pfeffer MA, et al: Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. NEJM 2015; 373: 2247-2257.

- Wanner C, et al: Empaglifozin and progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. NEJM 2016; 375: 323-334.

- Perkovic V, et al: Canaglifozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. NEJM 2019; 380: 2295-2306.

- Holman RR, et al: Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. NEJM 2017; 377: 1228-1239.

- Muskiet MHA, et al: Lixisenatide and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome: an exploratory analysis of the ELIXA randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6(11): 859-869.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(8): 18-20 (published 8/24/19, ahead of print).