On the occasion of the symposium “Modern Psychosis Therapies”, experts spoke on central aspects of the basics, early detection, prevention and treatment of psychoses. Individualized treatment planning based on guidelines on the one hand and changing acceptance of pharmacotherapy on the other hand lead to the question which components are relevant for a successful therapy.

“The lectures show how important it is to understand psychiatry as a union of psychology, the basics of neuroscience, sociology and also economic aspects that play into the overall concept of treatment,” Prof. Erich Seifritz, MD, Zurich, introduced the event. This multidimensionality of psychiatric diseases emerges in recent studies explained by Prof. Dr. med. Dieter F. Braus, Wiesbaden. In connection with the ENIGMA initiative, he humorously described this approach with the statement: “Neuro is written on it and psychiatry is in it. Studies from ENIGMA show that there are different signatures of different psychiatric disorders: For example, subcortical areas show significant structural differences between schizophrenia and major depressive disorder [2–4].

Primary psychosis is nowadays seen as a fundamental disorder of brain maturation [5]. Over the lifespan, microstructural changes emerge in different ways at different stages of life. For example, while cannabis may co-induce primary psychosis in early and mid-puberty, it may induce secondary psychotic disorder after puberty. A variety of changes are taking place in the brain, the critical two factors being myelination – white matter and connectivity – and loss of plasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt. Another important role is played by the dopaminergic, serotonergic, glutamatagenic systems, whose mechanisms of action on emotion, cognition, impulsivity, etc. have been intensively researched in the last 25 years and have given rise to new psychotropic drugs [6,7].

A newer area of research that has been able to develop, not least due to advances in digitization, concerns the encirclement of polygenetic diseases. Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder show genetic correlations and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Schizophrenia also [8,9]. Accordingly, stress-associated experiences and psychosis are related. This leads to a concept that is currently the subject of much international debate, namely that of genetic predispositions.

However, a single structural variant does not lead to a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, just as multiple vulnerability markers of genetic predispositions might not suggest this. In addition, environmental influence is necessary at vulnerable stages of brain maturation [10]. These can be diseases, stress, malnutrition and a related activation of the immune system. Depending on the genetic predisposition and which “insults” occur in which vulnerable phases of brain development, these lead to a “response”. This may be autism, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. Thus, immunological aspects come into focus in pathophysiology.

Stress and immunology have an impact on proinflammatory cytokines and thus on the sensitization of the child in the first 1000 days [11]. Recent evidence also shows that there is still extensive migration of young neurons in humans after the initial organogenesis phase in the first year of life. These later differentiate into interneurons, which also act to control dopamine and serotonin.

With these advances in neuroscience and genetics, our understanding of pathophysiology is increasing, while the complex interdependencies in the development of mental illness are becoming clear.

The crux of treatment recommendations

Prof. Dr. h.c. mult. Siegrid Kasper, MD, Vienna, led the auditorium through the variety of international treatment recommendations with a focus on the WFSBP guidelines*. One difficulty with guidelines in general is that some of them were developed a long time ago. For example, the the cited guidelines “Acute treatment of schizophrenia and management of treatment resistance” from 2012, their development probably took place in 2010. It is likely that some ratings for pharmacological products are no longer up to date, having been subjected to detailed practical review in Phase IV studies. Kasper pointed to lurasidone in this context. The same applies to the S3 guideline of the German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Neurology (DGPPN), which is currently being revised and should be completed this year. The evaluation categories of the guidelines must be taken into account; for example, meta-analyses have different weights in the respective evaluation systems of different guidelines.

Do not forget the body during treatment

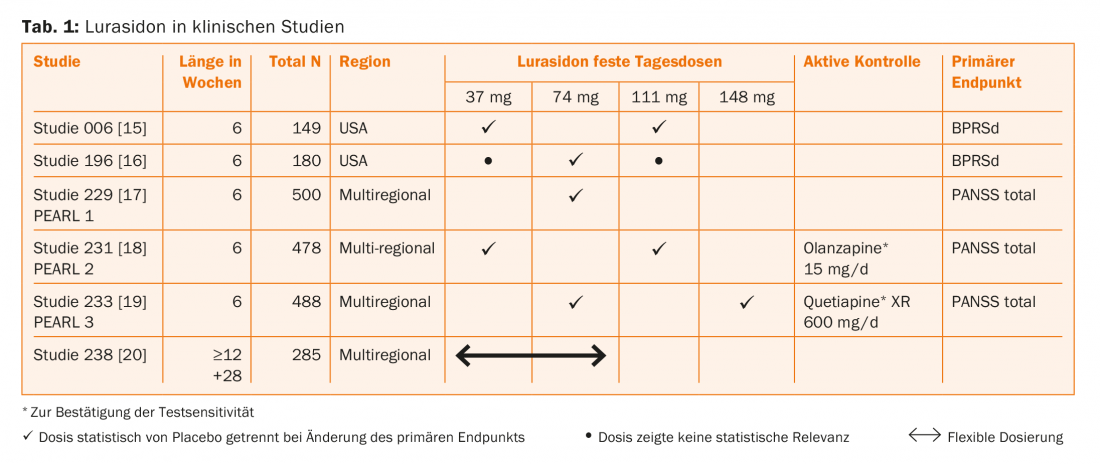

A clear reminder came from Prof. Dr. med. Gregor Hasler, Bern: Swiss and international studies prove [12] that people with severe psychiatric illnesses have a shortened life span (approx. 10 – 20 years). “Only a small part of this reduction is explained by the increased risk of suicide (5%),” Hasler said. Data collected from the public health system in Denmark show that schizophrenia patients do not benefit from the general steady increase in life expectancy, but stagnate at a constant level [13]. Another study shows the progression of weight gain in patients using psychotropic drugs [14]. Those who gain weight in the first few months have an increased risk of becoming overweight later. “The suspicion is that this is related to medication” said Hasler. “Dietary changes and nutritional counseling can positively influence weight progression. However, the long-term results of such measures are sobering.” With this in mind, Hasler emphasized the need to select antipsychotic medications with potential cardiometabolic risks in mind. Based on some studies, he argued that lurasidone has a relatively beneficial cardiometabolic profile (Table 1) [15–20].

Prof. Dr. med. Thomas J. Müller, Meiringen, also spoke about the problematic side of well-acting antipsychotics. He criticizes that it has not yet been possible to satisfy the needs of practitioners and patients with regard to a good efficacy/side-effect ratio. The new-generation antipsychotics have fewer psychomotor side effects, but metabolic and even cardiac side effects pose challenges, as Hasler detailed. However, the greater choice of antipsychotics today allows the practitioner to provide the best possible individualized fit.

A different perspective on the place of medications

Prof. Dr. med. Dr. phil Ambros Uchtenhagen, Zurich, also does not want the importance of medication in the treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders to be underestimated. He argued that not using medications is only possible in rare cases and tends to be the exception. It is important to embed the medication in an individually tailored treatment concept – just as the medication itself must be individually tailored to the patient, which Kasper already mentioned. For example, genetic predispositions can contribute to a drug being processed too quickly or not at all. The choice of substance and dosage require control and, if necessary, rework. For the required embedding, it is important that a sustainable therapeutic relationship exists between physician and patient, that the patient receives sufficient information, and that therapy planning is carried out jointly, Uchtenhagen warned, emphasizing the interpersonal component of therapy that is critical to success. Possible or existing side effects must be dealt with in an open exchange with each other.

In principle, a biological understanding of the disease can have a relieving effect on the patient, because questions of guilt are no longer the focus for the patient and he can concentrate on his therapy. However, an understanding of psychosis as a “brain disease” to be treated with medication can also have a depressogenic effect – that is, it can be understood as a fateful lifelong disability.

Prof. Uchtenhagen sees questions as the most important therapeutic instrument. They serve the understanding about situation and concerns of the patient, about choice and guidance of aspects relevant for the therapy and make avoidances tangible for the patient and therapeutically addressable.

Source: Symposium Modern Psychosis Therapy January 18, 2018, Zurich.

Organization and direction: Prof. Dr. med. Erich Seifritz

* World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia – a short version for primary care. www.wfsbp.org

Literature:

- Bearden CE,Thompson PM: Emerging global initiatives in neurogenetics: the Enhancing Neuroimaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA) consortium. Neuron 2017; 94(2): 232-236.

- Schmaal L, et al: Subcortical brain alterations in major depressive disorder: findings from the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder working group. Molecular Psychiatry 2016; 21(6):806-812.

- van Erp TG, Hibar DP, et al: Subcortical brain volume abnormalities in 2028 individuals with schizophrenia and 2540 healthy controls via the ENIGMA consortium. Molecular Psychiatry 2016; 21(4): 585.

- Schmaal L, Hibar DP, et al: Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Molecular psychiatry 2017; 22(6): 900-909.

- Davis J, Eyre H, et al: A review of vulnerability and risks for schizophrenia: beyond the two hit hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2016; 65: 185-194.

- Seeman P, Weinshenker D, et al: Dopamine supersensitivity correlates with D2High states, implying many paths to psychosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005; 102(9): 3513-3518.

- Murray GK, et al: How dopamine dysregulation leads to psychotic symptoms? Abnormal mesolimbic and mesostriatal prediction error signalling in psychosis. Molecular psychiatry, 2008; 13(3): 239.

- Sullivan PF, et al: Psychiatric genomics: an update and an agenda. American Journal of Psychiatry 2017; 175(1): 15-27.

- Horváth S, Mirnics K: Schizophrenia as a disorder of molecular pathways. Biological Psychiatry 2015; 77(1): 22-28.

- Giovanoli S, Engler H, et al: Stress in puberty unmasks latent neuropathological consequences of prenatal immune activation in mice. Science 2013; 339(6123): 1095-1099.

- Paredes MF, James D et al: Extensive migration of young neurons into the infant human frontal lobe. Science 2016, 354(6308): aaf7073.

- Choong E, Bondolfi G, et al: Psychotropic drug-induced weight gain and other metabolic complications in a Swiss psychiatric population. Journal of psychiatric research 2012, 46(4), 540-548.

- Nielsen RE, Uggerby AS, et al: Increasing mortality gap for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia over the last three decades-a Danish nationwide study from 1980 to 2010. Schizophrenia research 2013, 146(1), 22-27.

- Vandenberghe F, Saigí-Morgui N, et al: Prediction of early weight gain during psychotropic treatment using a combinatorial model with clinical and genetic markers. Pharmacogenetics and genomics 2016, 26(12): 547-557.

- Ogasa M, et al: Lurasidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a 6-week, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacology, 2013, 225(3): 519-530.

- Nakamura M, Ogasa M, Guarino J, et al: Lurasidone in the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2009; 70(6): 829.

- Nasrallah HA, Silva R, et al: Lurasidone for the treatment of acutely psychotic patients with schizophrenia: a 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Journal of psychiatric research 2013; 47(5): 670-677.

- Meltzer HY, Cucchiaro J, et al: Lurasidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-and olanzapine-controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 2011; 168(9): 957-967.

- Loebel A, Cucchiaro J: Efficacy and safety of lurasidone 80 mg/day and 160 mg/day in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-and active-controlled trial. Schizophrenia research 2013; 145(1): 101-109.

- Tandon R, Cucchiaro J: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study of lurasidone for the maintenance of efficacy in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2016; 30(1): 69-77.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(2): 39-42.