Varicose veins are a common problem. In Western society, it affects nearly one-third of adults. Unspecific complaints, sometimes falsely attributed to varicose veins, eventually lead these patients to the family doctor, where they should be closely examined and informed about the possible treatment options.

(ag) The cause of varicose veins, also known as varicose veins, is primarily inherited weakness of the connective tissue with weakening of the vein walls and valves, which causes blood reflux mainly into the superficial leg veins. In healthy individuals, the deep veins are squeezed with each muscle contraction and blood flows toward the heart. Reflux is prevented by the functioning venous valves. Thereupon, the muscles slacken again, resulting in a suction that draws blood from superficial and deep veins. Varicose veins, on the other hand, have damaged or inoperable valves and wall changes that allow blood to flow back toward the foot instead of the heart. Thus, a combination of hemodynamic problems, wall and valve changes is usually responsible for the condition. Risk factors that influence the development of varicose veins are prolonged standing or sitting, lack of exercise, too much heat, pregnancy, obesity, gender and age.

Truncal varicosis, in which one of the truncal veins is affected, often occurs in combination with side branch varicosis. Spider veins/reticular varicosis, on the other hand, is usually manifested by a spider web-like network, caused by tiny vein dilatations running almost parallel just under the skin. Spider veins can also cause discomfort and should therefore not be regarded exclusively as a cosmetic problem.

The most frequently affected by varicosis is the great saphenous vein. It runs from the inner side of the foot through the lower and upper thighs to the groin, where it joins the deep venous system.

What are the complications?

Despite the high venous pressure, many people do not experience varicose veins as a major physical impairment. Furthermore, the extent of varicosis is not directly related to the symptoms. Cosmetically, however, they can become a problem (protruding tortuous and dilated veins, bluish to brownish discoloration of the skin, especially on the inner lower leg). In addition, there are feelings of heaviness or tension, stinging, cutting or “formication” in the legs, itching and pain, increasingly in the evening or after long periods of standing. Varicose veins are also prone to inflammation. So-called superficial thrombophlebitis is a possible complication of varicosis, and the risk of developing deep vein thrombosis, although small, is still there, especially if the superficial phlebitis spreads to the thigh. Treatment of such thrombophlebitis is with anti-inflammatory analgesics.

Ways of diagnostics

Although a primary care physician can check the size and extent of the varices, preferably with the patient standing and in good light, to determine whether they belong to the great or parietal vein system, he or she should refer them to a vascular specialist for treatment and detailed evaluation.

A careful medical history is very important, since many patients complain of complaints that are not caused by varices. Determining the exact location of venous insufficiency is not necessary in family practice because clinical tests are inaccurate and Doppler sonography can be performed by vascular specialists.

What can be done about it?

In principle, a chronic disease is not curable. Treatment of varices should be considered in the presence of bleeding, skin lesions (for example, eczema or florid lipodermatosclerosis with hardened subcutaneous tissue), and ulcers. In order to be able to make an adequate decision for a certain therapy, the personal situation of the patient must always be taken into account. Older patients are more frequently sclerosed, while younger patients are more likely to undergo surgery because they still have a longer life expectancy.

The mainstay of therapy is still compression stockings. Overall, however, numerous options exist to address varicose veins:

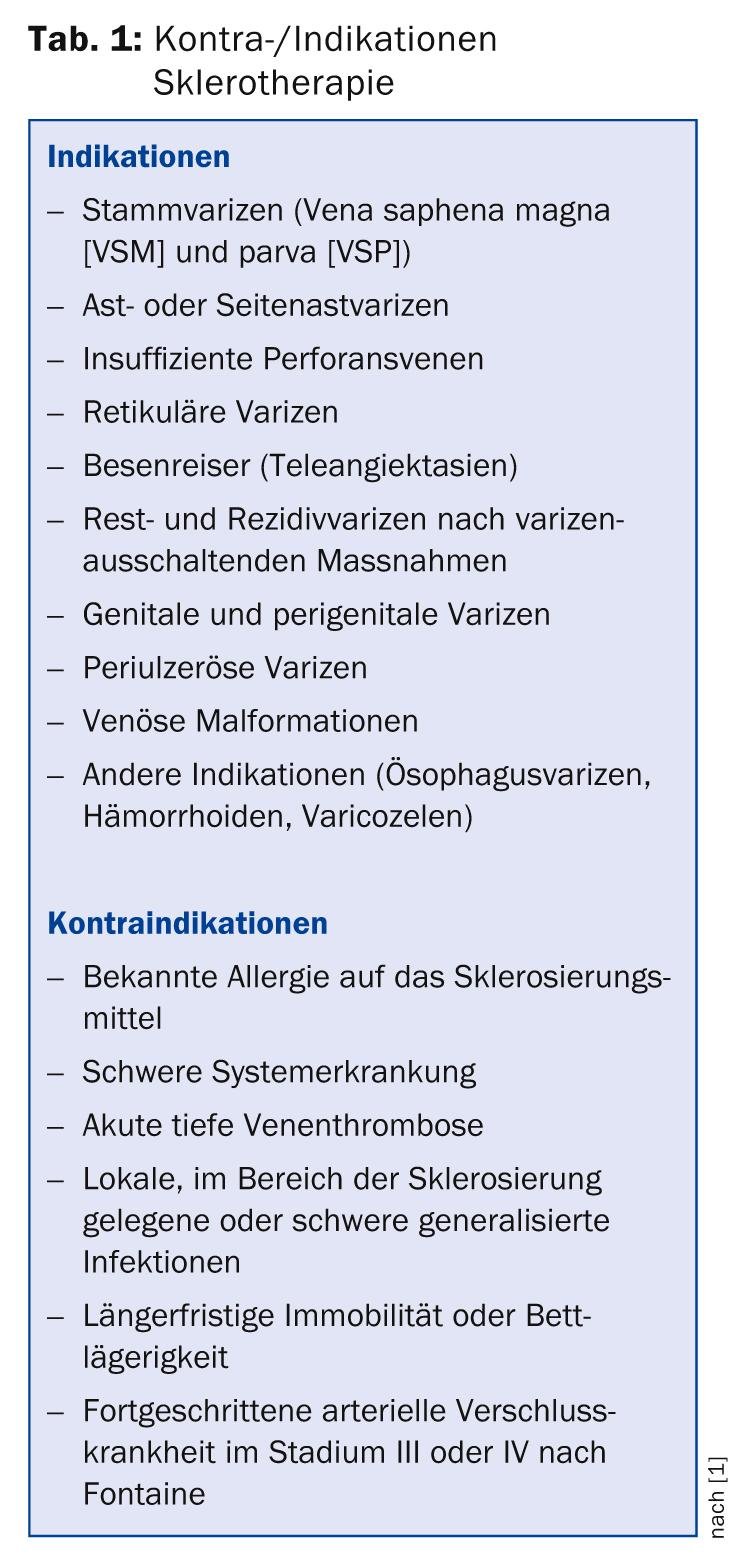

Sclerotherapy: This involves sclerosing the varices by injecting a sclerosing agent (usually sodium tetradecyl or polidocanol). This damages the endothelium of the vessels. If sclerotherapy is successful, there is a longer-term transformation of the veins into a connective tissue strand. Thus, one does not set thrombosis of the vessel as the goal, but definitive transformation into a fibrous strand that cannot recanalize and is equivalent in functional outcome to surgical excision. The aim is to treat varicosis and prevent possible complications. Pre-existing symptoms can be reduced or eliminated, and pathologically altered hemodynamics can be improved. In principle, all types of varicosis can be sclerosed. Indications and contraindications are shown in Table 1. This is the treatment of choice, especially for smaller varicose veins (reticular varicose veins). It is effective here and also makes sense from a cost perspective. Surgical stripping and endovenous thermal procedures are more commonly used for truncal varicosis.

In principle, sclerotherapy is well effective and has few side effects when performed competently. Possible adverse effects include allergic reactions (dermatitis, contact urticaria, erythema), skin necrosis (main risk), pigmentation (usually regresses slowly), teleangiectatic matting (individual reaction, can also occur after surgical elimination), damage to nerves, flicker scotomas, migraine-like symptoms (especially with the foam variant), an excessive sclerosing reaction (and thrombophlebitis), orthostatic collapse or thromboembolism (very rare exceptional cases, risk increased when using larger volumes or higher concentrations).

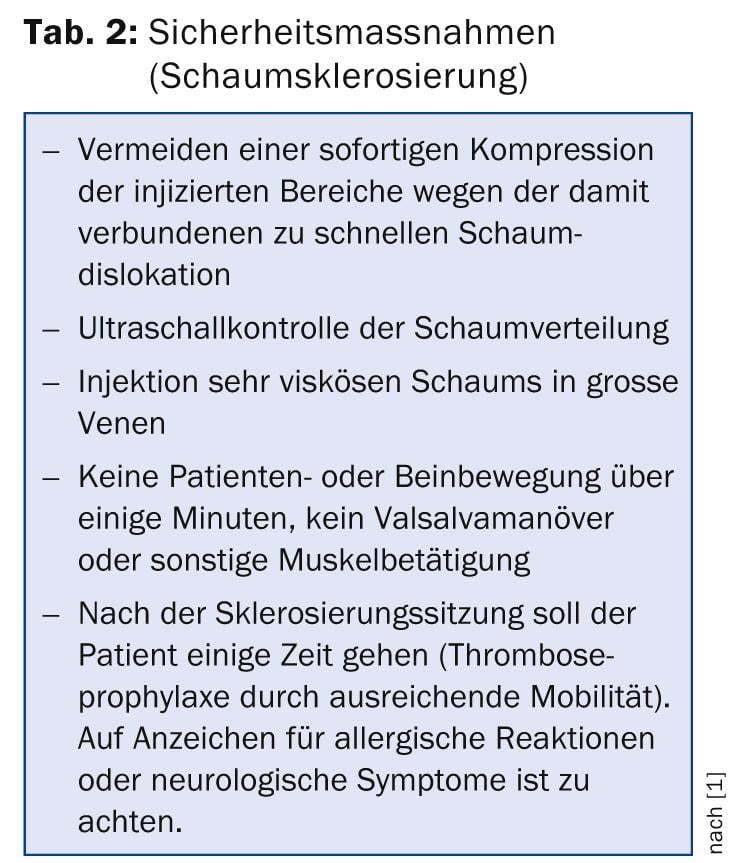

In foam sclerotherapy, the sclerosing agent is foamed with gases/air. In the vessel, this foam spreads rapidly and forces the blood to the side, resulting in venous spasm and more effective obliteration of long segments of superficial veins. Duplex sonography is used to check the position of the injection needle in the varicose vein and to monitor the spread of the sclerosing foam. Table 2 summarizes further safety aspects.

Both forms of sclerotherapy are followed by compression treatment with compression bandages or stockings.

Surgical procedures: Stripping has been used to treat varicose veins since 1906. Small incisions (side branch varidectomy, miniphlebectomy) are made on the inside of the leg and the dilated vein is pulled out using a probe. Before that, the vein and its small side branches are paralyzed.

Thus, conventional vein surgery usually consists of interruption of the connection between the great saphenous vein and the femoral vein in the groin (crossectomy) with phlebectomy of the varicose collateral branches and stripping of the great saphenous vein. Possible side effects include hematoma, which can be significant postoperatively in large varicose veins or obesity. Overall, however, the surgical risk is low and the procedure is technically simple.

Due to genetic predispositions, the tendency to develop new varicose veins remains, but rarely to the same extent as before surgery.

Endovenous/thermal procedures: Minimally invasive are endovenous thermal procedures. In this procedure, a catheter is inserted into the great saphenous vein via a puncture at knee level. It is then advanced toward the groin using ultrasound guidance, which eliminates the need for an incision in the groin and makes postoperative hematoma less likely. The vein is then gradually closed. These techniques may well make varices disappear, yet the majority still require sclerotherapy or phlebectomy.

Radiofrequency therapy is performed with a radiofrequency probe (VNUS), the heat generated at the tip of the probe leads to coagulation in the retraction process. The technique is performed under local or general anesthesia.

Laser therapy offers an alternative to vein stripping. A thin laser thread is inserted into the varicose vein. The physician then delivers laser energy via the optical fiber, which allows the vein in question to be closed in retraction. Usually, this procedure takes no more than an hour. Often small side branches remain open, which can later transport blood again and become varicose veins (higher recurrence rate than stripping).

Compression therapy: Compression therapy is the cornerstone of treatment and accompanies almost all therapy variants. The compression from the outside creates an abutment for the muscles. This improves the delivery capacity of the muscle-venous pump. The compression stockings must be individually fitted by a specialist. After a good half year, the stocking usually loses strength and should be replaced.

Sources:

- AWMF online: Guideline of the German Society of Phlebology. Sclerotherapy treatment of varicose veins (ICD 10: I83.0, I83.1, I83.2, I83.9). Current status: 05/2012.

- Poniewass N: Treatment of varicose veins: Therapy oldie beats laser technology. Spiegel online 21. 09. 2011.

- Wülker A: Varices and their treatment. What procedures are used today? Ars Medici 2007; 8: 429-430.

- Rohner H (Interview): Chronic venous insufficiency: What happens after varicose vein surgery? Ars Medici 2013; 21: 1083-1084.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(4): 6-7