Case report: A 30-year-old man with an unremarkable medical history suffered a focal clonic seizure of the left upper extremity, secondarily generalized. Five days earlier, the patient had a fever (38.6°) with cold symptoms. Physical examination was unremarkable except for a tongue bite, and EEG was normal. CSF puncture showed lymphocytic pleocytosis, normal glucose levels, and mildly elevated protein.

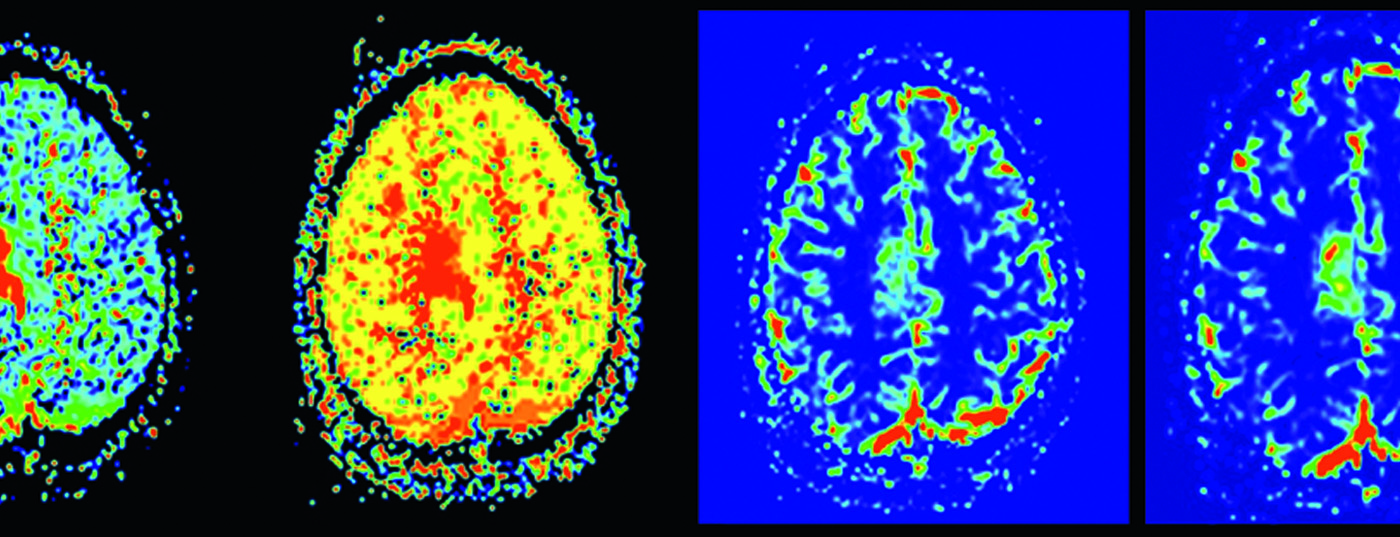

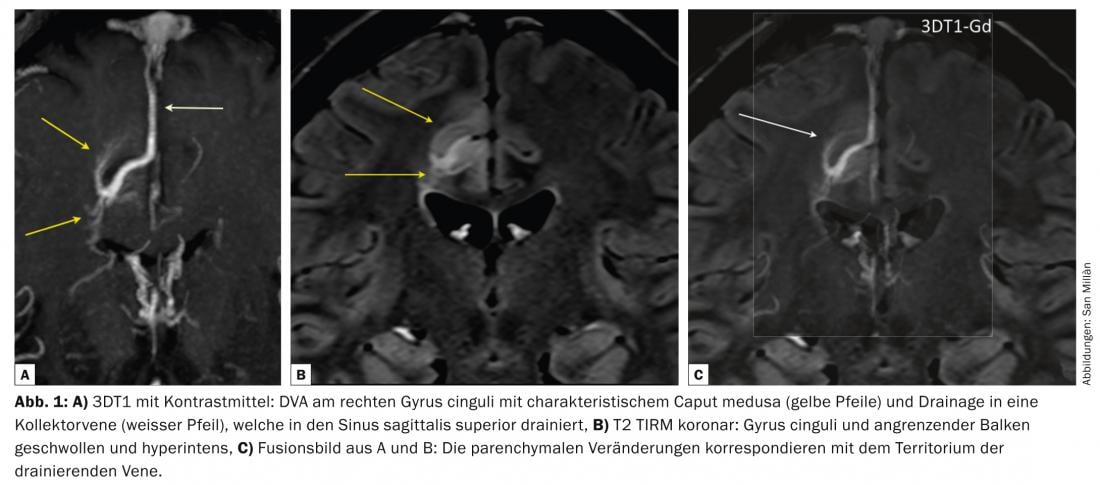

MRI of the skull performed five days after seizure revealed abnormalities in the right cingulate gyrus as well as in the corpus callosum in terms of edema; there was no restricted diffusion, hemorrhage, or contrast uptake. The parenchymal changes were localized in the territory of a DVA (“developmental venous anomaly”) draining into the superior sagittal sinus (fig. 1) . Perfusion MRI showed signs of venous hypertension in the territory drained by the DVA ( Fig. 2).

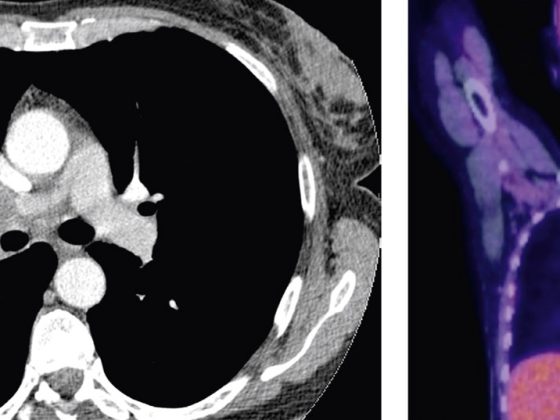

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) also showed signs of venous hypertension and stenosis of the collector vein without signs of thrombosis (Fig. 3).

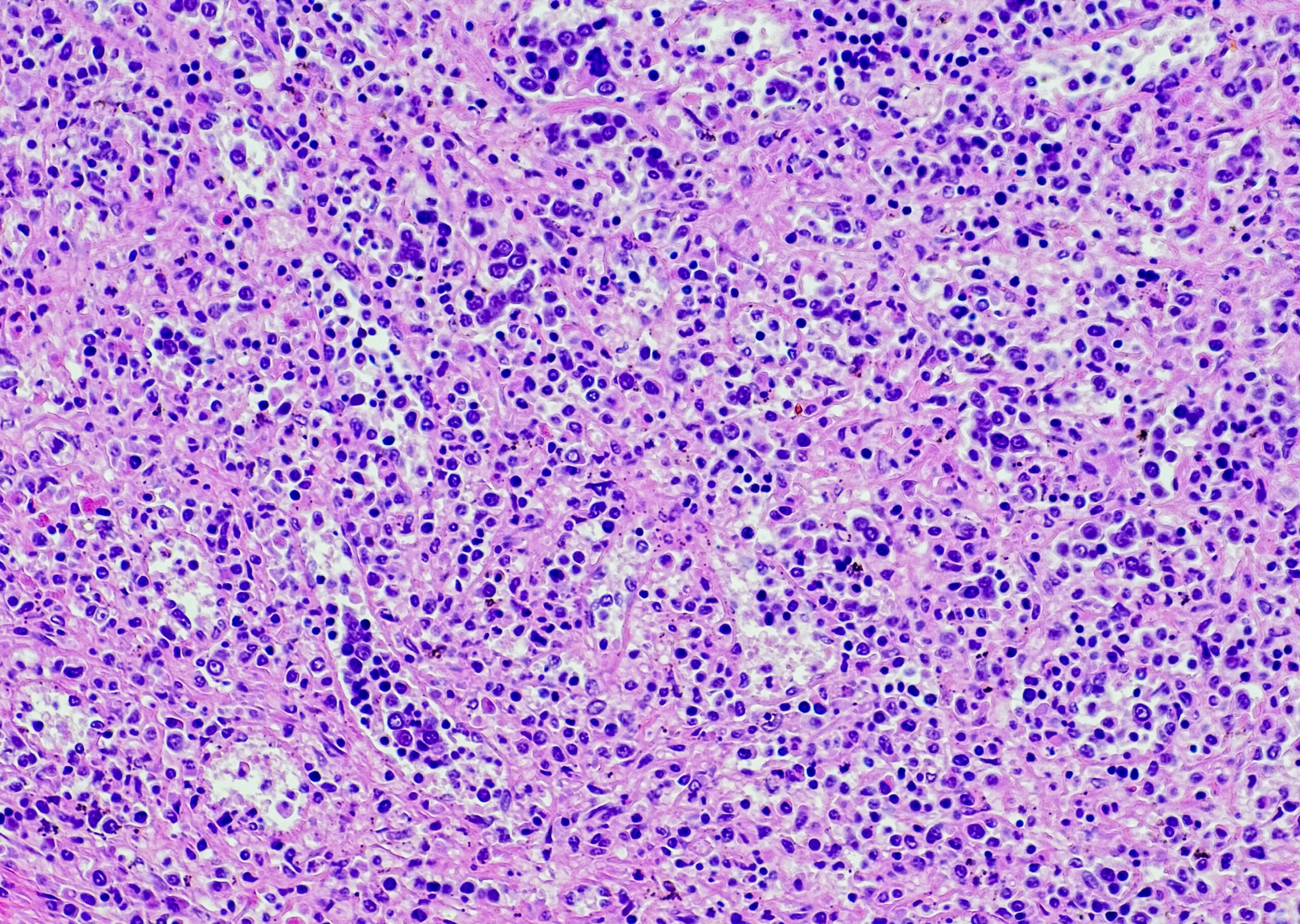

The patient recovered well with symptomatic therapy. Follow-up MRIs at one and 20 months showed slow regression of the morphologic abnormalities in the right cingulate gyrus with a persistent signal hyperintense change FLAIR-w in the adjacent bar as an expression of presumed gliosis (Fig. 4).

Discussion: DVA are the most common neurovascular malformations. They can be understood as a reconfiguration of the venous angioarchitecture. A DVA is responsible for venous drainage of a territory and therefore cannot be resected or can only be resected with the consequences of venous infarction.

Although DVAs are usually asymptomatic, they are not infrequently associated with locoregional parenchymal abnormalities, whether atrophy, cavernoma, or even dystrophic calcifications, changes that can be readily detected with CT or MRI examination. The development of venous hypertension by DVA may be due to several factors. First, a single vein drains an abnormally large venous territory; second, the walls of these veins have been shown to be thickened with decreased vascular compliance; and finally, stenosis of the draining collector vein may be present.

In the vast majority of cases, DVA remains asymptomatic; rarely, it may become symptomatic due to thrombosis; in these cases, anticoagulation is performed as in cortical venous thrombosis. Seizures due to an associated cavernoma represent the most common manifestation. In the case report presented, DVA was symptomatic without evidence of cavernoma or thrombosis. It is likely that meningitis lowered the seizure threshold.

Abstract: DVAs are very commonly detected on imaging and remain asymptomatic in the vast majority. As a variation of normal venous angioarchitecture, they may lead to locoregional venous hypertension with corresponding parenchymal changes.

Literature:

- Lasjaunias P, Burrows P, Planet C: Developmental venous anomalies (DVA): the so-called venous angioma. Neurosurg Rev 1986; 9: 233-242.

- Dillon WP: Cryptic vascular malformations: controversies in terminology, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997; 18: 1839-1846.

- San Millan Ruiz D, et al: Parenchymal abnormalities associated with developmental venous anomalies. Neuroradiology 2007; 49: 987-995.

- San Millan Ruiz D, Yilmaz H, Gailloud P: Cerebral developmental venous anomalies: current concepts. Ann Neurol 2009; 66: 271-283.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(1): 24-25.