Pregnancy increases the risk of a venous thromboembolic event. The risk is determined by various factors that can only be partially influenced. Updated guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) are available for the prevention and treatment of thromboembolic events in pregnant women.

The risk of a venous thromboembolic event (VTE)-which includes deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism-is increased by a factor of 4 to 5 during pregnancy [1, 2]. Among these, the incidence of VTE varies from 0.5 to 1.7 per 1000 births, and they are responsible for 1.1 deaths per 100 000 births [3]. Different data exist on how the risk progresses within a pregnancy. A 1999 meta-analysis concluded that the risk of VTE is the same in all three trimesters of pregnancy [4, 5]. Gherman et al. reported that half of all thromboses occur before the 15th week of gestation (SSW) [6]. And according to Pomp et al. the highest risk occurs in the third trimester [2]. In the puerperium, the risk of VTE is increased 20-fold [1, 6]. A case-control study from the Netherlands even shows a 60-fold increase [2]. The risk persists until 14 weeks after birth, but is highest in the first seven days [2].

Risk factors not always influenceable

The overall risk for VTE during pregnancy is composed of several components. “These are basic factors, some of which are congenital. And in addition, there are one or more acquired factors,” explained Prof. Wolfgang Korte, MD, St. Gallen. At the same time, it is not always possible to clinically perceive the presence of some of these factors. “Therefore, to assess thromboembolic risk, laboratory parameters should always be considered in addition to clinical findings.” In addition, there may also be interactions between the various risk factors. As an example, he cited the interactions between pregnancy and hormone therapy that can occur, for example, in the context of in vitro fertilization.

The greatest risk factor for VTE is considered to be a previous event; this is detectable in 15-25% of cases [3]. In second place are thrombophilias, which are detectable in 20-50% of cases [3]. A systematic review found that the risk here depends on the type of thrombophilia [7]. “A very relevant point is also the age of the pregnant woman,” Prof. Korte indicated. “Thus, from a purely epidemiological point of view, a primipara aged 35 years already has about twice the risk of VTE as a primipara aged 25 years.” This will certainly have to be taken into account more in the future, he said, as there are now some Western industrialized countries where the proportion of first-time mothers over the age of 30 is approaching 50%.

Anticoagulation during pregnancy

Prof. Korte went on to discuss the various options for anticoagulation in pregnant women. In this context, he recalled that vitamin K antagonists should not be used during pregnancy. “They cross the placental barrier and, depending on the dose, can cause malformations in a considerable proportion of exposed fetuses. It also increases the risk of bleeding in both mother and child.” He also explained that the new oral anticoagulants, such as rivaroxaban and apixaban, are placenta- and presumably milk-permeable due to their low molecular weight. “Therefore, they are contraindicated in pregnancy at this time.” Prof. Korte generally recommended risk-adapted therapy, also with regard to intensity.

Current recommendations

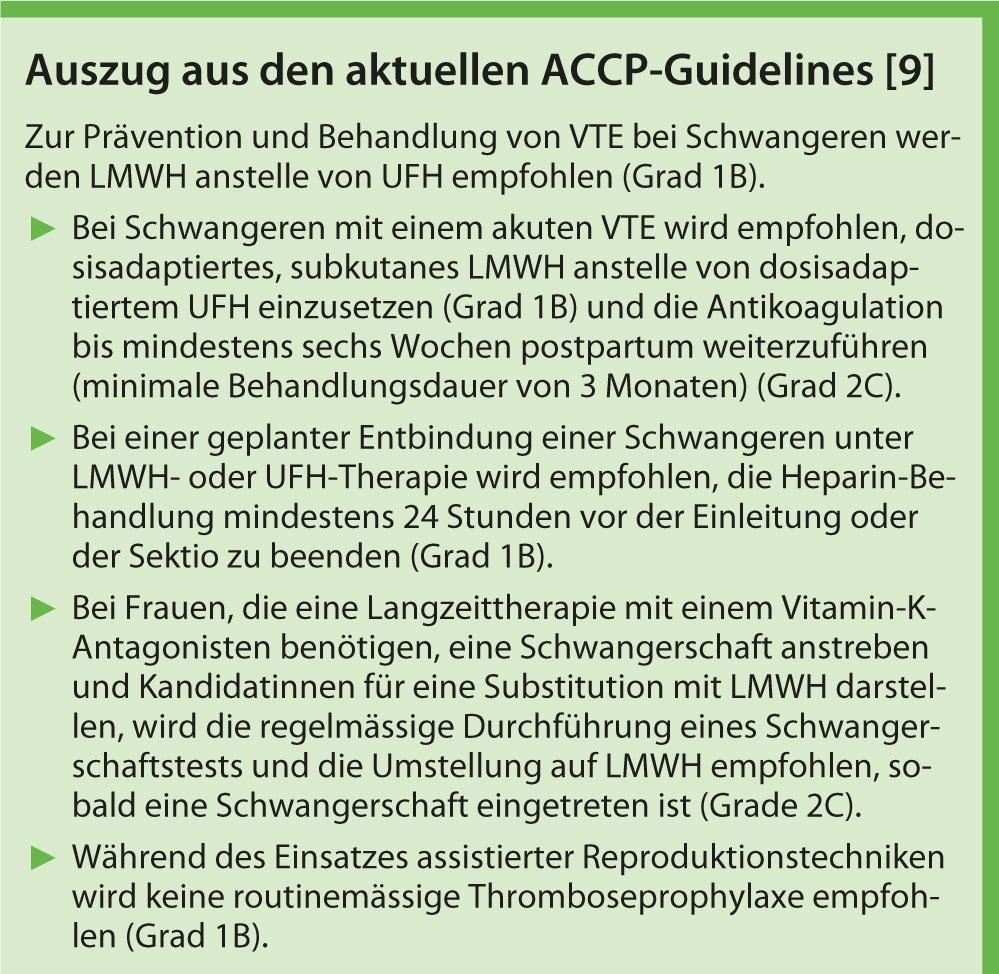

According to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), low-molecular-weight (LMWH) heparins are preferable to unfractionated (UFH) heparins because of lower complication rates, a favorable dose-response relationship, longer half-life, and better handling for the same efficacy [8]. The most recent version of the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) evidence-based recommendations gives LMWH a grade 1B recommendation for the prevention and treatment of VTE in pregnant women (see box) [9].

Source: Annual Congress of the Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (SGGG). Second main topic/ AFMM: thrombophilia and pregnancy. June 28, 2012, Interlaken.

Literature:

- Heit JA, et al: Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2005; 143: 697-706.

- Pomp ER, et al: Pregnancy, the postpartum period and prothrombotic defects: risk of venous thrombosis in the MEGA study. J Thromb Haemost 2008; 6: 632-637.

- James A: Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009; 29: 326-331.

- AWMF-S3 Guideline 003/001: Prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism (VTE); 2010. www.leitlinien.net/003-001I.pdf. (Association of the Scientific Medical Societies; AWMF).

- Ray JG, Chan WS: Deep vein thrombosis during pregnancy and the puerperium: a meta-analysis of the period of risk and the leg of presentation. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1999; 54(4): 265-271.

- Gherman RB, et al: Incidence, clinical characteristics, and timing of objectively diagnosed venous thromboembolism during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1999; 94: 730-734.

- Robertson L, et al: Thrombosis: Risk and Economic Assessment of Thrombophilia Screening (TREATS) Study. Thrombophilia in pregnancy: a systematic review. Br J Haematol 2006; 132(2): 171-196.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Green-top Guideline No. 37: Reducing the risk of thrombosis and embolism during pregnancy and the puerperium. Nov. 2009.

- Bates SM, et al: VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141(2 Suppl): e691S-736S.