Since the turn of the year, popular media have been reporting on the Zika virus at an impressive rate. Switzerland does not have to fear any direct effects of the epidemic. Nevertheless, the current awareness can be taken as an opportunity to once again emphasize mosquito protection in travel medicine (and general practitioner) consultations. At present, this is the only effective means of preventing transmission.

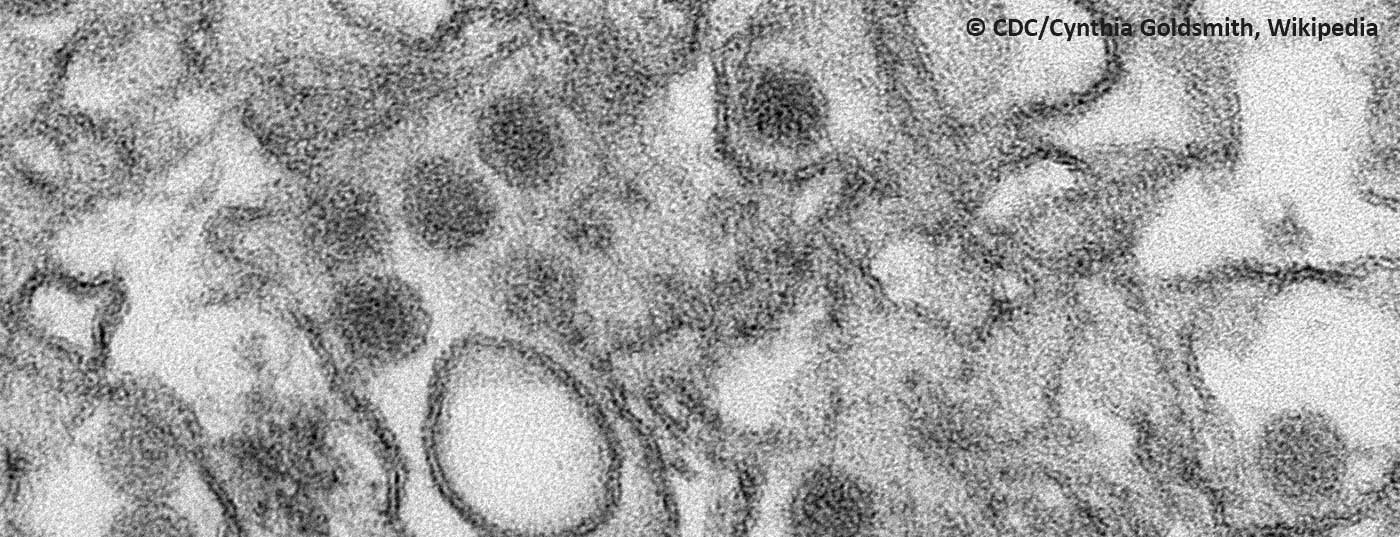

The information on the virus that has been secured so far should be sufficiently known by most Swiss physicians. As a reminder, this is a virus originally from the African Zika forest, but now mainly rampant in Latin America, the Caribbean and the South Pacific, which after transmission (mainly by the mosquito species Aedes aegypti) causes self-limiting moderate symptoms such as mild fever, headache, joint pain and rash in only 20% of cases, but is strongly suspected of causing microcephaly in the unborn child and other neurological damage. Likewise, human-to-human sexual transmission has been observed. Both processes have not yet been fully clarified scientifically; corresponding studies are underway. Recently, the virus was detected for the first time in the brain of a fetus with microcephaly [1]. Because no pathologic changes or viruses were detected in any other fetal organ, severe neurotropism can be assumed, the authors said.

What is certain is that not every child whose pregnant mother has had the infection will develop malformations. The phenomenon was not known in this way from previous Zika outbreaks in Africa and Asia. In addition to Zika, genetic or metabolic causes or drug use, perinatal hypoxia or other infections could be responsible for microcephaly.

Status: March 1, 2016

Meanwhile, the affected countries of Latin America, led by the host of the upcoming Olympics, Brazil, are making Herculean efforts to tackle the epidemic through mosquito control and public education. WHO, in an emergency meeting in early February, declared the cases of microcephaly and other neurological disorders reported in Brazil and French Polynesia to be a “health problem of international concern” (previously, Ebola, polio, and swine flu, for example, fell into this category). According to WHO, there is a strong spatial and temporal association between the spread of the virus and the incidence of malformations. Although conclusive scientific proof is still lacking, the time has come to intensify international cooperation. Pregnant women should reconsider travel to named regions and discuss with their physicians.

The Swiss Expert Committee for Travel Medicine, however, clearly advises pregnant women not to travel to the affected areas. Women of childbearing age are advised to avoid pregnancy for at least three menstrual cycles after their trip.

There are currently very few valid data on virus transmission through breastfeeding. For the time being, according to WHO, the many benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the potential risks of transmission, so no specific restrictions are recommended here. Both potentially infected persons and mothers of children with microcephaly should breastfeed normally.

As for other mosquito-borne diseases, the primary principle is prevention through mosquito repellent (repellents, light-colored protective clothing, mosquito netting at night). Primary care providers who are in regular contact with potential travelers have the opportunity to take advantage of the current heightened awareness and strongly recommend a visit to an appropriate center or to a tropical physician if they plan to travel to the tropics. Also, the basic principles of mosquito protection can not be mentioned often enough. Pregnant women returning home from an affected country should be advised by their primary care physician to consult a gynecologist. The Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics has published specific information on this topic.

Some laboratory-confirmed cases have been reported in Europe and also in Switzerland, all from returnees from affected areas. According to current knowledge, there is no risk of infection in our latitudes. This is because the vector mosquito Aedes aegypti does not occur in our country. Although it is theoretically possible that the local Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) will carry the virus, widespread establishment of the virus is not expected. Also because the mosquito species in Switzerland is active in an opposite cycle to the epidemic in Latin America.

Although many questions also remain about sexual transmission, travelers and returnees from an affected country should be advised to use condom contraception and follow standard safer sex rules in light of confirmed cases of transmission. However, the duration of sexual transmission risk is not yet known.

Media uproar justified?

The current excitement about the Zika virus is certainly related, on the one hand, to the upcoming Olympic Games in Brazil and the government’s related efforts to make the country appear to be a safe travel destination. On the other hand, the images of newborns with microcephaly and the idea that the virus causes great harm to the unborn undetected are distressing and provide an excellent projection surface for fears and feelings of latent threat. It is often forgotten that other viral diseases (e.g. the dengue virus, which is related to the Zika virus) have been rampant in the same countries for many years. Also somewhat neglected in current reporting is Guillain-Barré syndrome, another rare but very troubling potential consequence of Zika infection. Just a few days ago, on February 29, a case-control study demonstrated a clear association in this regard [2].

Valuable information on Zika is provided by the following organizations:

www.bag.ch

www.safetravel.ch

www.cdc.gov

www.who.int

www.sggg.ch

Literature:

- Mlakar J, et al: NEJM 2016 February 10. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651.

- Cao-Lormeau VM, et al: Lancet 2016 February 29. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(3): 6