Antipsychotics are the mainstay of acute and long-term treatment for schizophrenic disorders. The earlier antipsychotic treatment begins, the greater the chance of controlling or stopping the progression of psychosis.

The term schizophrenia was coined by Eugen Bleuler and first published in 1911 in his monograph Group of Schizophrenias. To this day, this 108-year-old technical term for the major psychotic disorder is still in use. Six years ago, DSM-5, the American Diagnostic Manual, introduced the term “schizophrenia spectrum disorder.” However, the first truly effective treatment for schizophrenic disorder was not available to psychiatric hospitals until 1952/53. This therapy was drug-based: Chlorpromazine. Chlorpromazine was transferred directly from the Paris Psychiatric University Hospital to the Basel University Hospital as early as 1952 by Felix Labhart. It can be assumed that this was done without much bureaucratic effort at the time.

A brief history of neuroleptics/antipsychotics

Chlorpromazine/Largactil® led to an upheaval in institutional psychiatry at the time in the years that followed. According to Prof. Raymond Battegay, the so-called “agitated” departments with the agitated psychotics suddenly became less noisy and much more relaxed. New and more humane ways of dealing with these seriously mentally ill people were now possible.

The term “neuroleptic” comes from the Greek and was introduced into the scientific literature by Delay and Deniker in 1955. The goal was to develop an “etiologic” model for the mode of action of the new antipsychotic drugs. The two Frenchmen had discovered that chlorpromazine has sedative and anxiety-relieving effects. Accordingly, it has been used for psychomotor agitation predominantly in schizophrenic patients.

The introduction of neuroleptics opened an important door in the treatment of schizophrenic disorders. First, it was a reversible treatment (e.g., in contrast to the lobotomies still in use at that time), and second, the effect was rapid and effective. This led to a massive reduction in the length of stay of psychotic people in the institutions of the time, which relieved the overcrowded hospitals. Relapses occurred when patients discontinued the medication. Reasons were the lack of disease insight or not insignificant side effects such as massive sedation, parkinsonism (EPMS) or photosensitivity.

Discovery of dopamine as a neurotransmitter

Around the same time that chlorpromazine was introduced into psychiatric hospitals, Arvid Carlsson (1923-2018) in Sweden discovered dopamine, its structure and function as an important neurotransmitter in the brain. Carlsson and Lindqvist’s work also established the dopamine hypothesis of psychosis later proposed by van Rossum and Snyder and still valid today. This states that dopamine antagonists, i.e., neuroleptics or antipsychotics, post-synaptically occupy dopamine receptors (especially D2 receptors) and thus block the neurotransmission of dopamine. The result is an improvement in the positive symptoms of schizophrenic disorders. While typical neuroleptics primarily improve delusions and hallucinations, they show little effect on or even worsen the disease features later referred to as negative symptoms, such as affective flattening, alogia, social withdrawal, and apathy. Here, clozapine and the atypical antipsychotics, which are better known as serotonin-dopamine antagonists, brought a clear expansion of the spectrum of action.

Introduction of antipsychotic medications.

After the introduction of chlorpromazine in 1952, various so-called tricyclic neuroleptics were approved over the next 20 years, some of which are still available today:

- From the phenothiazine group of substances (chlorpromazine, levomepromazine, fluphenazine, promazine and triflupromazine),

- From the substance group of thioxanthenes (chlorprothixene and flupentixol).

During the same time period, other neuroleptics with non-tricyclic structures but similar side effect profiles were approved:

- From the substance group of butyrophenones (haloperidol, pipamperone, melperone),

- From the substance group of diphenylbutylpiperidines (fluspirilene and pimozide/ no longer on the market today).

The above classification by structural chemistry is based on the textbooks by Möller et al (2015) and Kaplan Sadock (2015).

In 1972, clozapine (discovered as early as 1959) was approved in Switzerland, showing a special profile of action and a different spectrum of side effects than the previous neuroleptics. The FDA did not approve clozapine until 1990, so the U.S. did not discover its uniqueness until later. As the first “atypical anti-psychotic” it originated:

- From the substance group of dibenzodiazepines (clozapine): this group is also called the “pines” by St. Stahl in his textbook because of their ending: Cloza-pin; These include olanzapine, quetiapine (both closely structurally related to clozapine); asenapine and zotepine. What these substances have in common is their multireceptor profile.

Other atypical antipsychotics:

- From the substance group of benzisoxazoles (risperidone and ziprasidone); for the sake of simplicity, the umbrella term “dones” (risperi-dones) suggested by St. Stahl is also used for the substances that are similar in terms of receptors: Risperidone, Paliperidone, Lurasidone, Ziprasidone. These have less “rich” receptor pharmacology than the “pines” and at higher doses with EPMS have similar UAWs to the dopamine-only antagonists. Risperidone and paliperidone may also cause a prolactin increase in a dose-independent manner.

- From the substance group of piperazine derivatives (aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine). These substances show a novel and pharmacologically very interesting effect. They are partial dopamine agonists. St. Stahl calls them “two pips and a rip,” based on their names: ari-pip-razole, brex-pip-razole, and ca-rip-razine; in our country, they are memotechnically referred to as the ABCs of partial dopamine agonists.

Common to all these novel compounds (“pines/dones/two pips and a rip”) is combined serotonin (5-HT2A) and dopamine D2 antagonism. They were introduced in Switzerland after 1990. Aripiprazole has been available in Switzerland since 2004, and cariprazine and brexpiprazole have been approved since 2018. This was followed in Europe (not in the United States) by the introduction of other novel antipsychotic agents from the benzamide group of substances (sulpiride in 1972 and amisulpride in 1999); amisulpride is also considered an atypical antipsychotic, although it is predominantly a D2 and D3 antagonist. At higher doses, EPMS are known to occur and, most importantly, significant prolactin elevation.

Partial dopamine agonism

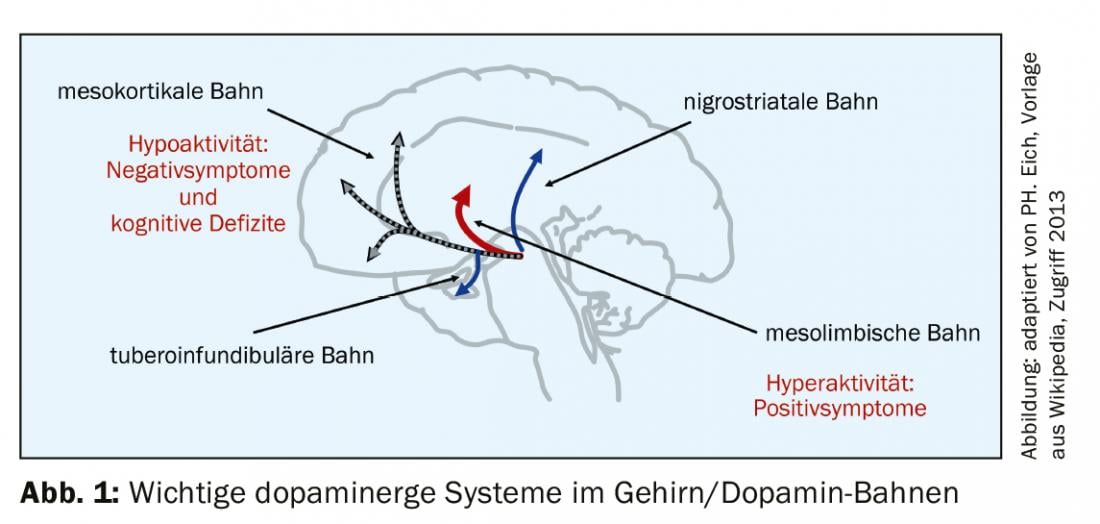

The rationale for partial dopamine agonism is optimal compensation of dopaminergic dysregulation associated with psychosis (dopamine hypothesis of psychosis). The background is the known dopamine pathways in the brain (Fig. 1) . Under these conditions it makes sense,

- Decrease dopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic pathway (improve positive symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations through antagonistic action).

- enhance dopaminergic activity on the mesocortical pathway (negative symptoms, including cognitive deficits improve due to agonistic effect on the dopamine receptor)

- exert no effect on the nigrostriatal or tuberoinfundibular pathways (no change in motor function, no EPMS, and no prolactin increase).

Aripiprazole achieves this effect by simultaneously blocking the postsynaptic D2 receptor and the presynaptic autoreceptor. The result is a partial agonist effect, also intrinsic dopamine effect of about 30%. Too much antagonism brings the substance close to the classical dopamine antagonists, too much agonism leads to the enhancement of psychotic symptoms.

All three partial dopamine agonists have the constellation typical of atypical antipsychotics with antagonism on the serotonin axis with 5-HT2A, but with the aforementioned partial agonism for the D2 receptor and also for the 5-HT1A receptor, which could be an explanation for the antidepressant effects of the compounds.

Aripiprazole shows little pharmacological evidence of sedation (low H1 blockade and low M1 muscarinergic/anticholinergic effect). In addition, it has little weight-increasing and low diabetogenic effect. Aripiprazole has been available in Switzerland since 2004 and is available to clinicians in both oral and intramuscular forms, as well as in sustained release.

According to St. Stahl, brexpiprazole is a weaker dopamine agonist than aripiprazole, but it shows stronger antagonism on the 5-HT2A receptor, stronger partial agonistic effects on the 5-HT1A receptor, and more alpha-1 antagonism. This means little EPMS and especially less akathisia.

Cariprazine behaves similarly to brexpiprazole in terms of antagonism (5-HT2A) and partial agonism (D2 and 5-HT1A), but has additional partial agonism for the D3 receptor, which is thought to promote dopamine release in the mesocortical area. The would be favorable for the treatment of negative symptomatology. The akathisia-reducing properties of brexpiprazole are less present with cariprazine. In addition, as with aripirazole, the histamine receptor is moderately blocked, which may explain some fatigue (St. Stahl, 2013).

The differences between the three partial dopamine agonists have been compiled by L. Citrome, 2018, noting that the comparisons are not weighted head-to-head but indirectly compared to placebo (Table 1).

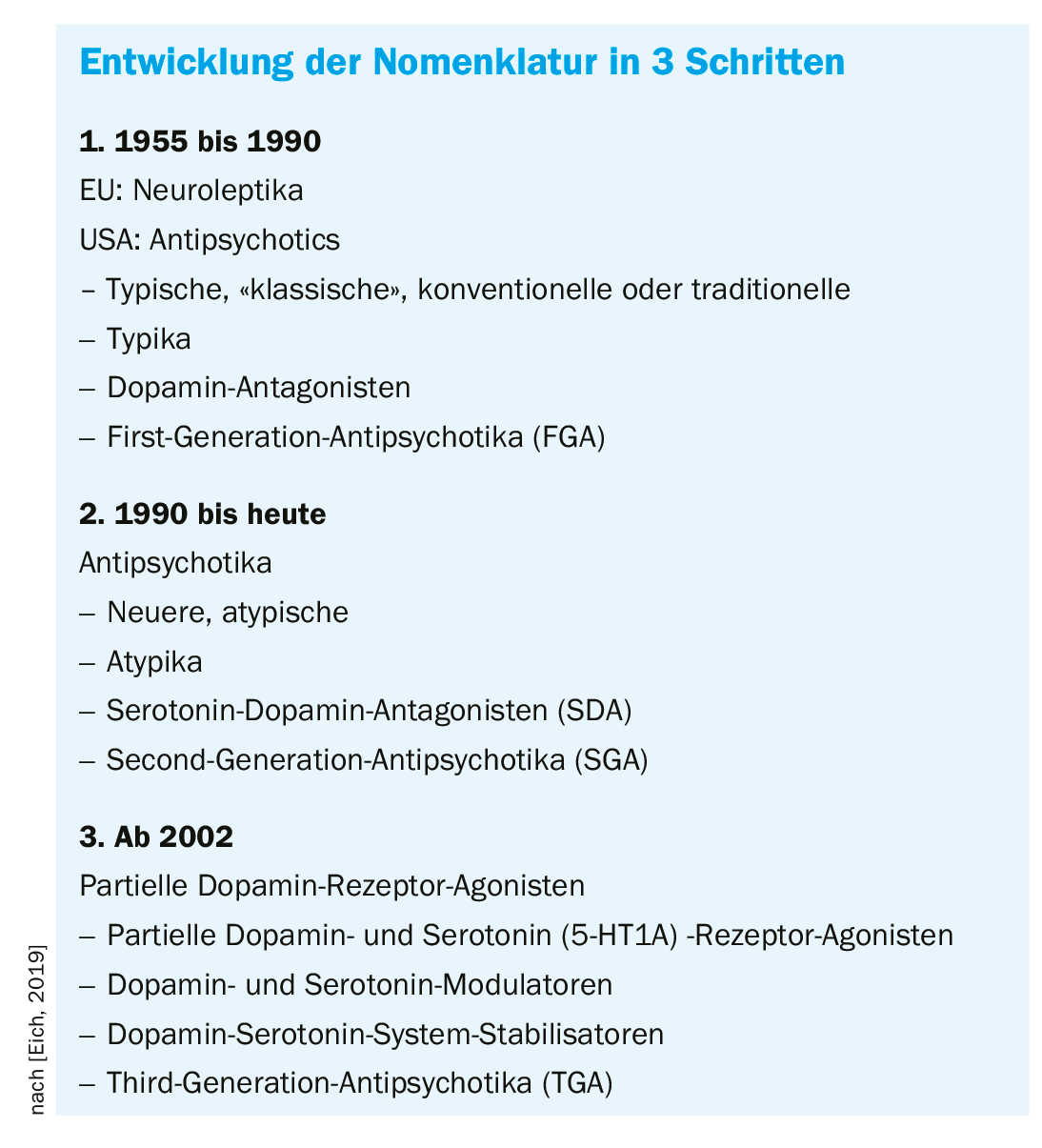

Nomenclature of antipsychotics

The structural chemical designation of antipsychotically active substances was used primarily in scientific publications and when new substances were introduced. It was not very practical in daily prescribing practice. Most antipsychotics introduced to the market before clozapine (CH 1972/USA 1990) differed in dose range and sedation (low-potent versus medium-potent versus high-potent), but in terms of EPMS frequency there are only minor differences (Overview 1).

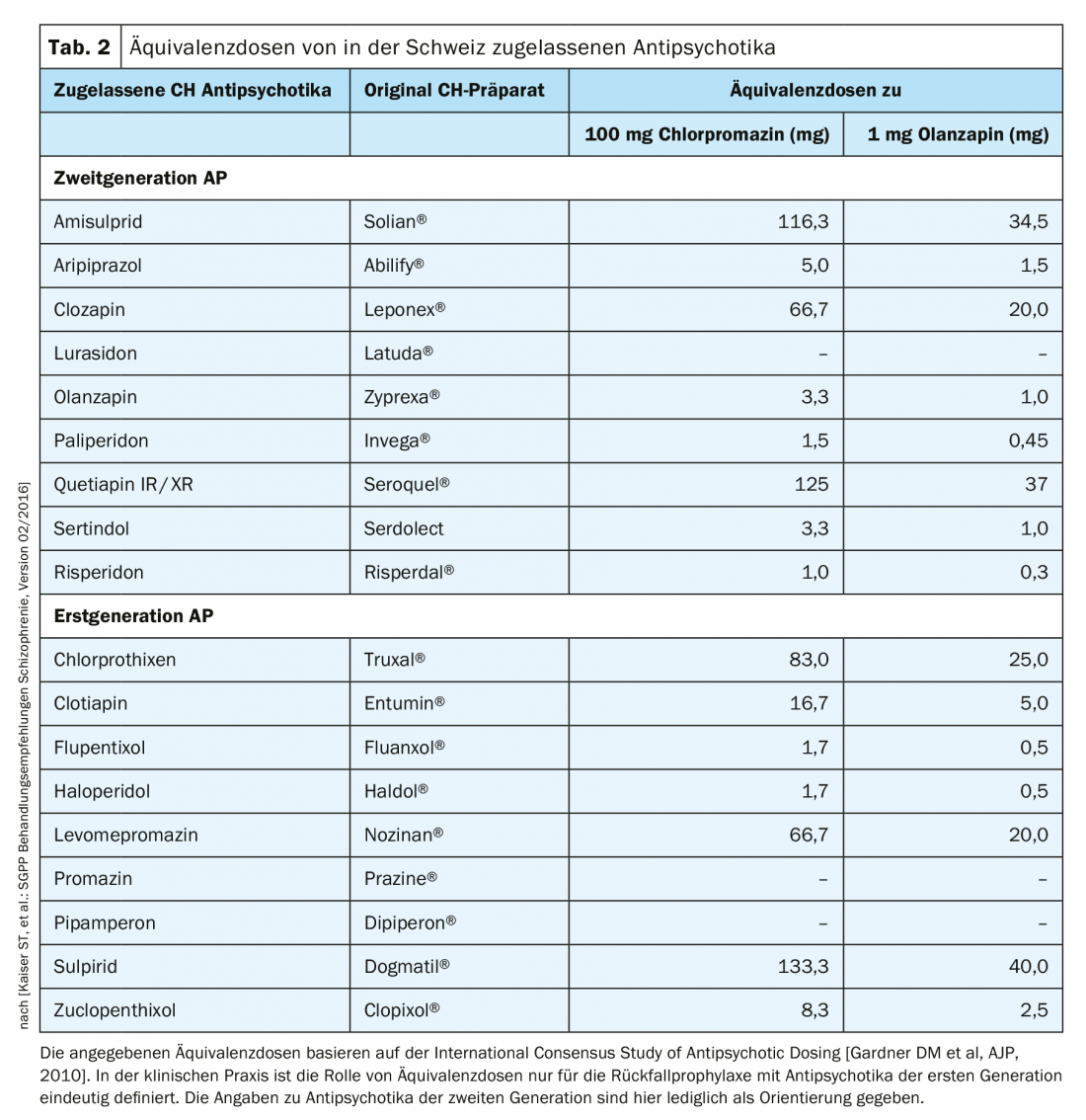

Adoption of this classification by antipsychotic potency and derived dose-equivalence tables traditionally calibrated to 100 mg chlorpromazine are now obsolete for atypical antipsychotics and difficult to establish because of the very different side-effect profiles. The Swiss working group led by St. Kaiser et al. nevertheless included such an equivalence assessment of atypical antipsychotics, as measured by 1 mg olanzapine, in the 2016 treatment recommendations (Table 2). Clozapine does not provoke EPMS, tardive dyskinesia, or prolactin elevation. Its side effect profile is associated with, for example, agranulocytosis, weight gain, or sialo-rrhea. Thus, clozapine was the first to be assigned to the new group of atypical antipsychotics.

In contrast to European, especially German-speaking psychiatry, the term “antipsychotics” became established early on in English-speaking countries instead of neuroleptics. At the latest since the introduction of clozapine in the USA in 1990, only antipsychotics have been spoken of and a distinction made between typical and atypical substances. Synonymously and mainly in textbooks, they are classified into first-generation antipsychotics (FGA) and second-generation antipsychotics (SGA), respectively. This does not refer to a uniform class of substances, as the newer antipsychotics are structurally very different and have considerably different receptor profiles. Generally, in the English-language scientific literature, all antipsychotic agents introduced after 1990 are referred to as “atypical antipsychotics” (Maudsley Guidelines, 2018). In recent years, a new nomenclature has been propagated by the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP), which classifies substances according to pharmacology and mode of action: Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN2, 2018). Only time will tell whether this sophisticated classification will prevail. After all, in their standard textbook of psychiatry, Kaplan Sadock (2015) refer to the typical antipsychotics as dopamine antagonists and the atypical agents as serotonin-dopamine antagonists, as they share this principle of action (development of nomenclature).

What does this academic discussion do for the patient?

Patients are usually primarily skeptical/critical when prescribed antipsychotics. What is important to them above all is an effective effect without adverse drug reactions.

Making or keeping good antipsychotics from the patient’s perspective (excerpt):

- No cramping symptoms (EPMS)

- No restlessness in movement (akathisia)

- No heavy tongue, no swallowing problems (EPMS, early dyskinesia).

- Stable body weight

- No sedation/being sedated

- Potency/Libido

- No flattening of affect

- No “dependence

- No “gene damage

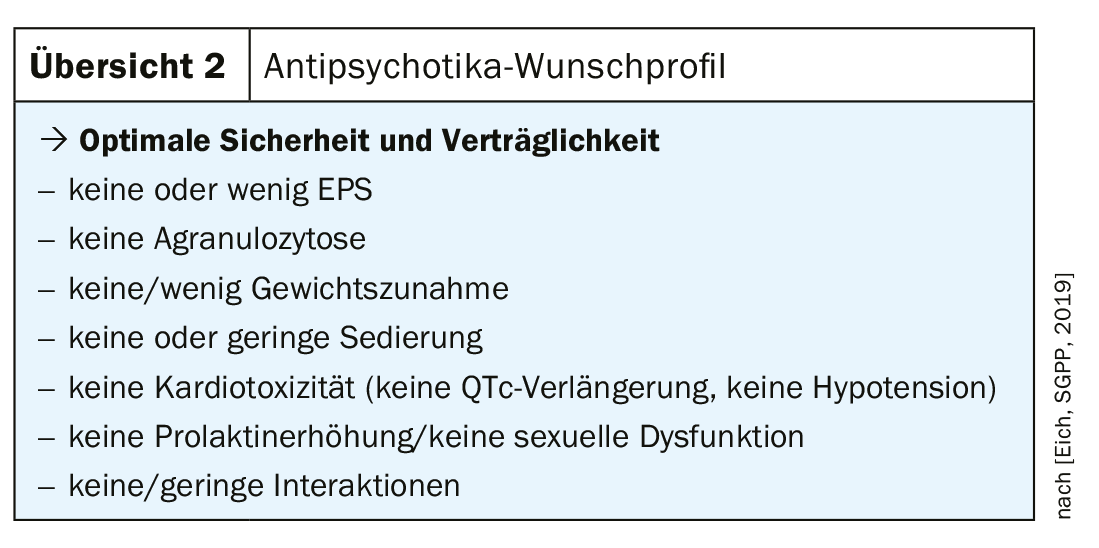

When selecting an antipsychotic, therefore, attention should be paid to optimal safety and tolerability with good efficacy (overview 2) . At the same time, the above criteria are crucial for recommending the most suitable drug for the individual. It is important to proceed in the spirit of shared decision making and to take the patient’s wishes into account.

For first-episode psychotic patients (FEP), most international guidelines recommend the administration of an antipsychotic of the 2nd generation, with those of the 3rd generation can also be subsumed under it. This also applies to the Swiss treatment recommendations (Kaiser et al. 2016/18). 1st generation antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol) are now the second choice in the treatment of psychotic disorders. The exception is use in delirium treatment (Eich PH, Nick B. 2018).

Conclusion

Modern pharmacotherapy of schizophrenic disorder must serve multiple functions, i.e., the treatment perspective on patients is multifocal. It shall at the same time:

- Know the first-generation antipsychotics and be aware of their advantages and disadvantages.

- Be effective with as few adverse drug reactions (ADRs) as possible.

- Be personalized, i.e., tailored to those affected (if appropriate indicators are available)

- Be restitutive with the goal: Restitutio ad integrum, i.e. function-preserving and rehabilitative

- Be embedded in community-based care that meets needs

From a clinical perspective, the Antipsychotics of the 2. and 3rd generation clear advantages over typical substances. With regard to Hippocrates and his principle: “Primum non nocere – secundum cavere – tertium sanare” (first, do no harm/do not set harm – second, bear caution – third, heal/contribute to healing/author‘s translation), the partial dopamine agonists with their favorable side effect profile are absolutely first-choice drugs.

Take-Home Messages

- Antipsychotics remain the mainstay of acute and long-term treatment of schizophrenic disorders today. Historically, we currently have a fairly wide range of modern antipsychotic agents to choose from.

- The order of pharmacological treatment is based on the psychopathology and the level of suffering of the affected patients. It should be noted that the earlier antipsychotic treatment is started, the greater the chance of controlling or stopping the progression of psychosis.

- Non-adherence is the most important relapse factor.

- The use of antipsychotics should be discussed in shared decision making; a good knowledge of mode of action and potential ADRs is a prerequisite.

- 3rd generation antipsychotics (aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine) are an important step in the right direction.

Further reading:

- Citrome L: Current Psychiatry, 17(4), April 2018.

- Eich PH, Nick B: Special issue “Schizophrenia”, Therapeutische Umschau, 01/2018.

- Kaiser ST, et al: SGPP treatment recommendations for schizophrenia, February 2016 version; www.psychiatrie.ch/sgpp/fachleute-und-kommissionen

- Kaiser ST, et al: SGPP treatment recommendations for schizophrenia, Swiss Med Forum 2018; 18(25): 532-539.

- Taylor D, et al: The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry 13th edition, Wiley Blackwell, 2018.

- Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN-2R), published by ECNP, 2018.

- Falkai P, Wittchen HU: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5, APA, 2013; Hogrefe 2015.

- Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry, 11th Edition, Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

- Möller HJ, Laux G, Deister A: Psychiatry, psychosomatics and psychotherapy, 6th edition, Thieme Verlag, 2015.

- Stahl ST: Essential Psychopharmacology, 4th ed, Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Woggon B: Behandlung mit Psychopharmaka, 3rd edition, Huber Verlag, 2009.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(6): 16-21.