Traumatic brain injury (SHT) is often trivialized in sports [1]. Short- and long-term consequences may occur, such as motor disorders that can lead to further injuries, loss of performance, dizziness, nausea, impaired concentration. The reasons for this trivialization can only be conjectured. Certainly, the attitude of highly motivated athletes to want to be active again quickly, the lack of detectability of any damage and the lack of qualified medical personnel on site are part of it.

As in the

first part of this series of articles

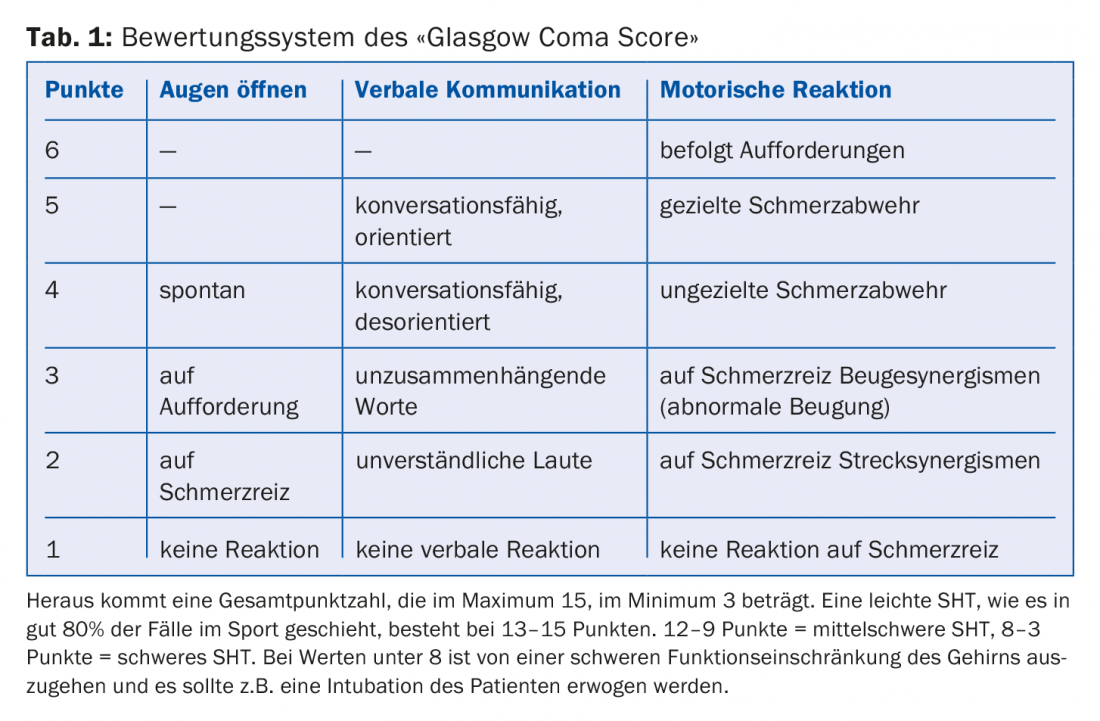

explained, recognizing a mild traumatic brain injury in sports at the scene is the most important measure. Observation of the accident and determination of the initial symptoms are the basis of a correct determination of the further procedure. At this point it should be emphasized that concussion does not at all necessarily lead to loss of consciousness, amnesia and vomiting, which is still erroneously believed. But these signs can be present, of course. The acute signs of mild SHT that occur within seconds to minutes after the force is applied are headache (occurring in nearly 95% of cases), dizziness (75% of cases), disorientation, slurred speech, nausea, balance problems, visual disturbances, fatigue, sensitivity to light, sensitivity to sound, and others. These somatic symptoms may also be accompanied by cognitive disturbances such as confusion, slowed reaction time, difficulty concentrating (reported in 68% of cases), and by emotional signs such as mood lability, irritability, aggressiveness. In conventional trauma medicine, the “Glasgow Coma Score” is still used for traumatic brain injury (Table 1).

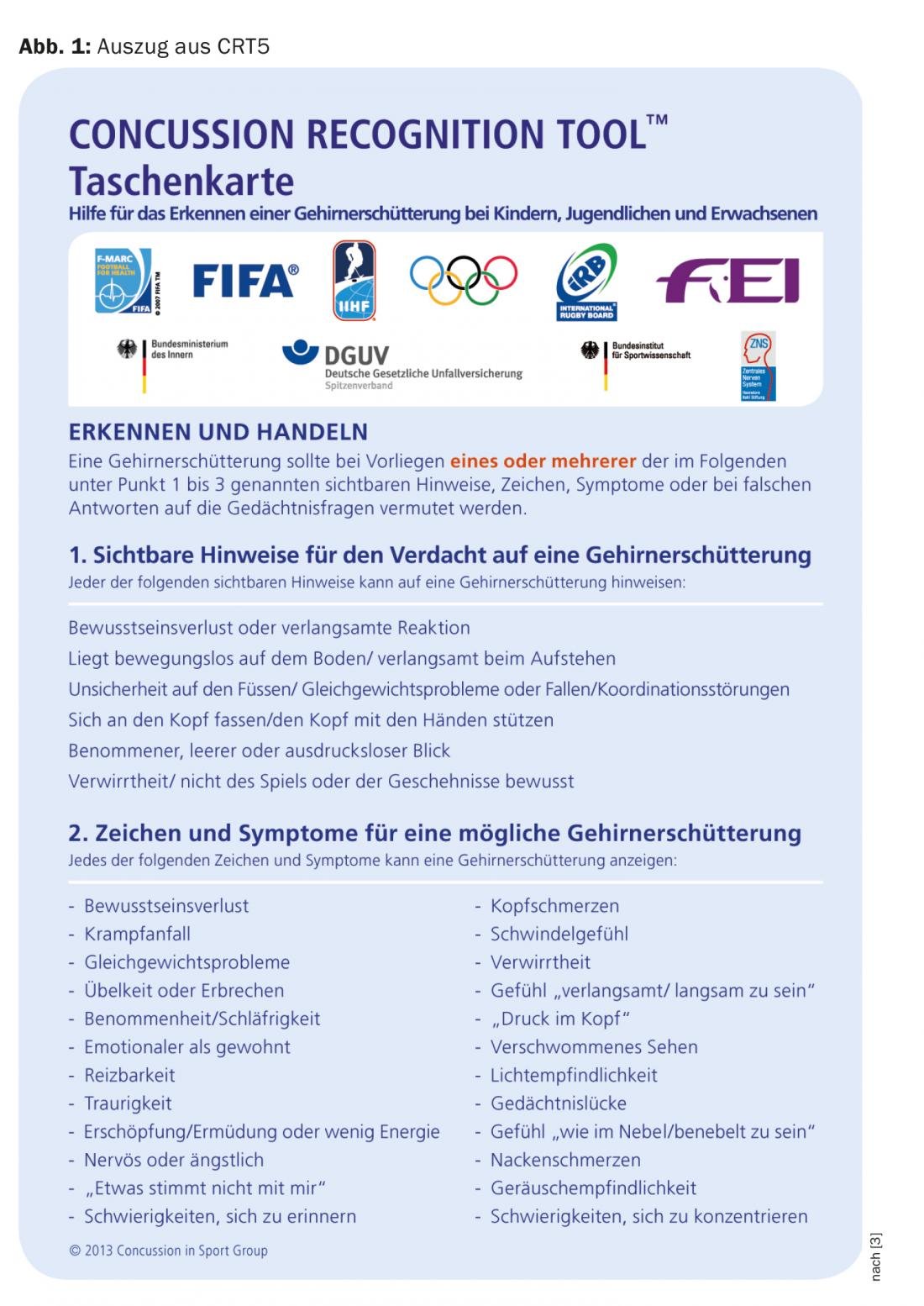

If one or more of these clinical features are present with appropriate trauma sequelae, commotio cerebri is likely, and the appropriate medical interventions must be initiated. The first one is called “sport stop”, in other words, the sport activity should be stopped immediately in order to organize the further clarifications in peace. In English it is called “When in doubt – take him out”. In order to systematically perform these important initial assessments at the scene of an accident, there are practical tools developed by the leading sports federations, for example the so-called “Concussion Recognition Tool Pocket Card” of the DFB (Fig. 1) [3], a German-language version of the “Concussion Recognition Tool 5 (CRT5)” [4].

From the moment the athlete is taken out of the competition, he/she should be looked after and monitored, i.e. not left alone – if possible in a quiet and darkened room. At this point, a small intermediate remark is allowed: The action of damaging biomechanical forces directly on the head or also indirectly on other parts of the body with transmission to the head can in certain cases trigger more than one SHT, and it is recommended to relocate the injured athlete or remove the helmet with appropriate caution: cervical spine injuries are quite possible combination injuries! As soon as possible, a medical assessment should be made to determine whether hospitalization (always after loss of consciousness) and further technical investigations (X-ray, CT, MRI, etc.) are indicated. A useful tool, called the SCAT-3 document, has also been developed for this step [5,6]. This document also exists for children.

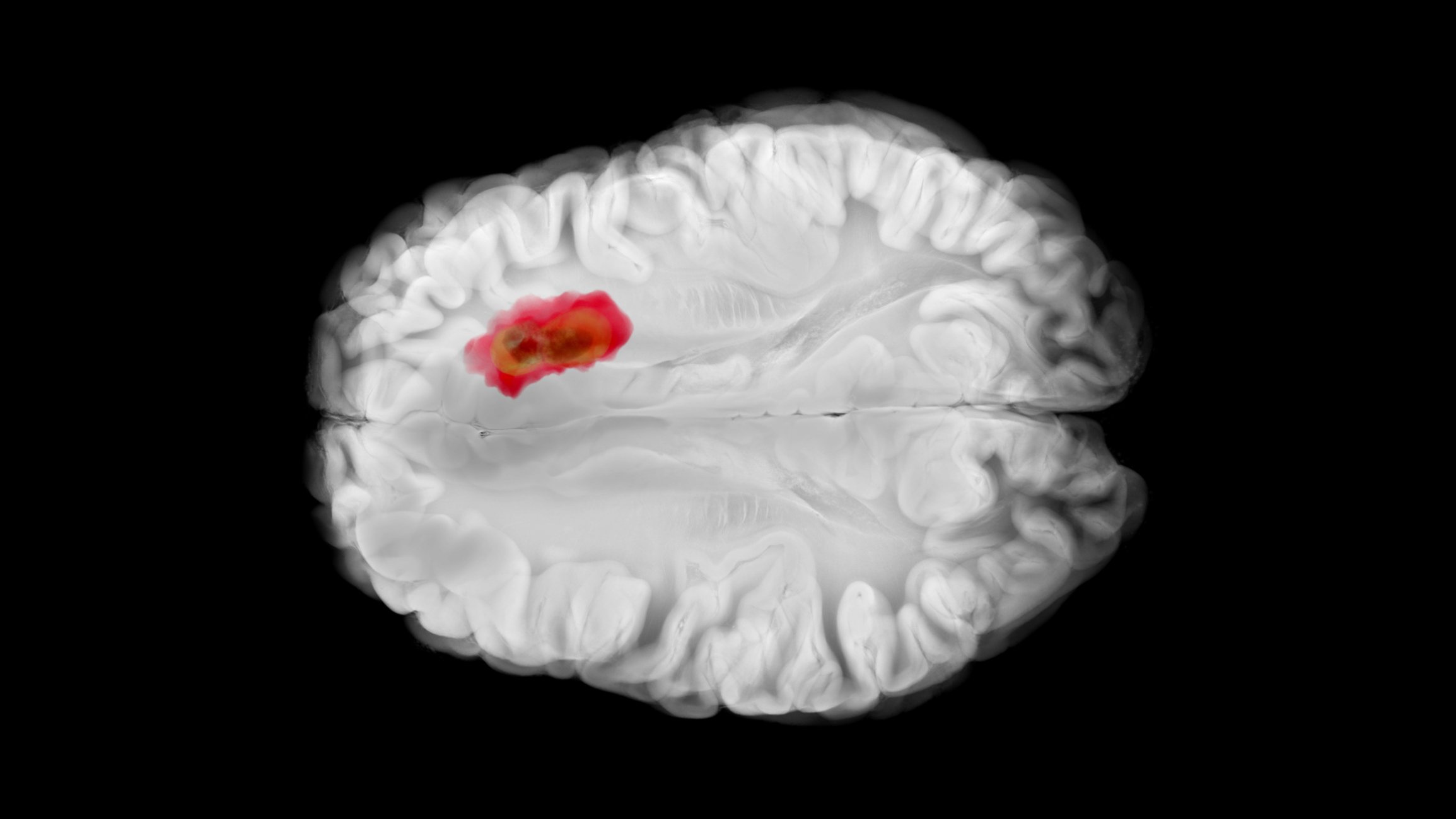

Various research groups are looking for a biological marker, preferably detectable in the blood. Recently, the U.S. FDA approved such a compound (Banyan Ubiquitin C-terminal Hydrolase-L1TM (UCH-L1) [7] and Banyan Glial Fibrillary Acidic ProteinTM [GFAP]) [8], and active research is being conducted in Oslo at the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center (Tau protein and neurofilament light chain in serum). We can also expect a lot from functional MRI in the future.

Regarding the treatment of sports-related concussion, it must be made clear that no specific therapy is known at this time. The goal is to reestablish the function between neurons in the brain that has been disrupted by the trauma and to restore subtle connectivity. For this purpose, rest, that is, a strict reduction of external stimuli of all kinds (light, noise, intellectual activities) seems to have the best effect. Although there is no absolute evidence yet on how long this rest should last, 24 to 48 hours seems appropriate. Only when this acute phase is over and its symptoms have completely disappeared can there be any talk of resuming physical and mental activities. In a good 85% of cases, the situation should be normalized after one week, and in more than 95% of cases, there is full functionality after one month. However, changes are still found on functional MRI after one year.

However, this does not mean that the way back to sport is open. There is a return-to-sport concept based on six stages (= days). For each permitted activity, the athlete must be absolutely symptom-free before proceeding to the next level. Conversely, if any problems occur during the load, then the program must be restarted at the previous level or repeated until there are no more complaints. The six stages are:

Mental and physical rest until there is freedom from symptoms

- Light physical exertion such as walking, exercise bike

- Sport-specific loads such as running, skating

- Training without physical contact

- Training with body contact

- Competition-like activity

The Return-to-Sport program requires a great deal of patience, personal responsibility and discipline from all involved to protect the brain from further damage. Once again, it must be strictly emphasized that entering competition activities too early, when symptoms are still present, means a real risk for the athlete.

Described in this way, the whole matter seems to proceed quite linearly, and often it does in sports. However, one must be aware that there are less favorable courses even in mild concussions, and these should be seriously addressed. For such courses it is worthwhile to approach the problems in a multidisciplinary way with neuropsychological, vestibular and ophthalmological tests best in specialized centers (e.g. Swiss Concussion Center in Zurich).

Literature:

- Cusimano MD, et al: Assessment of head collision events during the 2014 FIFA World Cup Tournament. Jama 2017; 317(24): 2548-2549.

- Teasdale G, Jennett B: Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 1974, 2: 81-84.

- Concussion Recognition Tool 5 Pocket Card (CRT5) www.dfb.de/fileadmin/_dfbdam/130132-LSHT_taschenkarte.pdf

- Concussion Recognition Tool 5: CRT5) http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/bjsports/early/2017/04/26/bjsports-2017-097508CRT5.full.pdf

- SCAT 3: http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/bjsports/47/5/259.full.pdf)

- German language tools: www.schuetzdeinenkopf.de/LSHT_handouts/LSHT_publikationsliste/LSHT_flyer_mediziner/

- Diaz-Arrastia R, Wang KK, et al: Acute biomarkers of traumatic brain injury: relationship between plasma levels of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 and glial fibrillary acidic protein. Journal of neurotrauma 2014; 31(1): 19-25.

- Papa L, Lewis L, et al: Elevated levels of serum glial fibrillary acidic protein breakdown products in mild and moderate traumatic brain injury are associated with intracranial lesions and neurosurgical intervention. Annals of emergency medicine 2012; 59(6): 471-483.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(7): 3-4