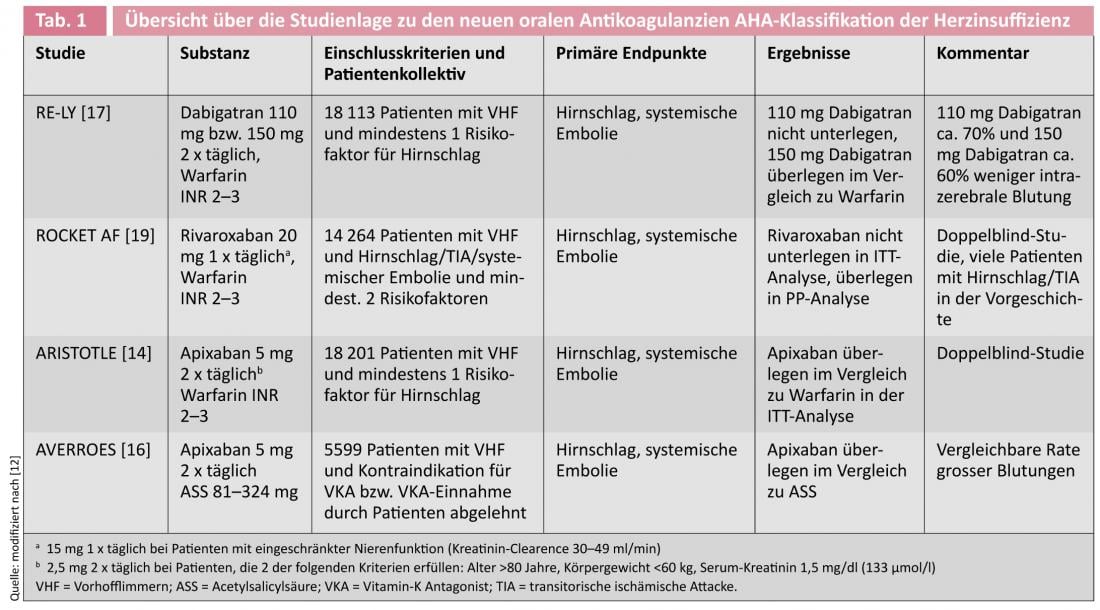

In primary and secondary prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), after a long period of monopoly of vitamin K antagonists (VKA), new agents such as dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban have provided evidence of equal efficacy. The new compounds appear to show clear advantages over the “old” VKA (fixed dosing, no coagulation controls, fewer interactions with food and other drugs). However, based on the current study situation, none of the new substances can be identified as having a clear advantage over the others.

Which patients are candidates for primary or secondary prevention in VCF for the new oral anticoagulants? From today’s point of view, these are patients with VHF whose adjustment to a therapeutic INR proves difficult with VKA or who do not wish regular blood sampling or whose implementation is difficult (e.g., long distance to the nearest physician). This can also be applied to patients after cerebral stroke due to atrial fibrillation.

Which patients (continue to) receive VKA? There is no indication to switch patients who have been stable for years under VKA therapy and, in particular, have stable INR values within the therapeutic range to one of the new substances. Also, therapy with VKA will continue to be necessary in patients with severe renal insufficiency or patients who require therapy with a drug that interacts with the new OAKs (e.g., ketoconazole) or have another indication for VKA (e.g., a mechanical heart valve replacement).

The overall prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) is 0.4-1% in the population, making it the most common cardiac arrhythmia in adults, with the prevalence increasing from <1% in those under 60 years of age to approximately 8% in those over 80 years of age [1]. Cerebral stroke is a feared complication of VCF. The risk of stroke is increased 5-fold by atrial fibrillation independent of other risk factors [2].

Avoiding thrombus formation is the key therapeutic strategy for primary and secondary prevention of stroke in patients with VCF. For this purpose, oral anticoagulants (OACs) from the group of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs, e.g. warfarin in the USA and phenprocoumon or acenocoumarol in Europe) have been used for decades. Their efficacy in the prevention of ischemic stroke has been proven since the early 1990s [3, 4]. They are among the most effective therapies ever in preventing cerebral embolic events, with a relative risk reduction of 64% and an absolute risk reduction of 2.7% per year compared with placebo. 37 Patients need to be treated with a VKA to prevent stroke [5, 6]. This applies to both primary and secondary prevention.

Under these aspects, this form of therapy can be considered very successful. Nevertheless, in clinical practice, only about 60% of patients who have an indication for VKA are treated accordingly [7].

Treatment with vitamin K antagonists is associated with several pharmacologic obstacles and challenges. Continuous monitoring of the dosage with measurement of the anticoagulant effect (International normalized ratio, INR) is required. The effect is often individually unpredictable and dependent on various polymorphisms [8, 9]. Interactions with other drugs and with food are problematic and require dose adjustment. Concomitant diseases also lead to altered metabolism.

The development of new substances from the group of oral factor Xa and thrombin inhibitors has provided new options in the field of oral anticoagulation. Their effect has been demonstrated by some substances in corresponding efficacy studies and they have recently been approved for the prophylaxis of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation in Switzerland A new era in the history of oral anticoagulants seems to have been initiated [10]. Is the king (VKA) dead [11]? Do we no longer need VKA [12]? What properties do the new substances have? The following will attempt to answer these questions. We briefly summarize the current study situation and address practical aspects.

Apixaban

Apixaban (Eliquis®) is a direct factor Xa inhibitor. It is largely eliminated hepatobiliary with about 25% also being excreted renally [13]. The efficacy of apixaban in the prevention of stroke has been tested in two large clinical trials.

In the ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation) trial, 18 201 patients with VCF were treated with a dose of 5 mg apixaban twice daily or warfarin [14, 15]. The rate of primary endpoint events (stroke or systemic embolism) after a mean observation period of 1.8 years was 1.37% in the apixaban group and 1.60% in the warfarin group (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.66-0.95; p=0.01 for superiority). Major bleeding occurred statistically significantly less frequently in the apixaban group at 2.13% per year than in the warfarin group at 3.09% per year (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0-60-0-80; p<0.001). Mortality was reduced by 11% (HR 0.89, 95%CI 0.80-0.99; p=0.047).

A second study, the AVERROES (Apixaban versus Acetylsalicylic Acid to Prevent Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation Patients Who Have Failed or Are Unsuitable for Vitamin K Antagonist Treatment) trial, evaluated the effect of apixaban (dosage 5 mg twice daily) compared with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) (dosage 81-324 mg daily) in 5599 patients, who had VCF and either had contraindications to warfarin therapy or were unwilling to undergo such therapy [16]. The primary end point (cerebrovascular accident or systemic embolism) was identical to the ARISTOTLE trial.

The study was stopped early by the Data and Safety Committee because clear superiority of apixaban could be calculated. The average observation period was 1.1 years. A total of 51 endpoint events were observed in the apixaban group (1.6% per year) and 113 in the ASA group (3.7% per year) (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0-32-0-62; p<0.001). The bleeding rate was not statistically significantly different with 44 cases (11 intracerebral hemorrhages, ICB) in the apixaban group (1.4% and 0.4% ICB per year, respectively) versus 39 (13 ICB) cases in the ASA group (1.2% and 0.4% ICB per year, respectively) (HR for apixaban, 1.13, 95% CI 0-74-1.75; p=0.57).

Dabigatran

Dabigatran etexilate (Prodrug) or dabigatran (Pradaxa®) is a direct thrombin inhibitor that has been available on the European market since 2008 and has also been approved in Switzerland since May 2012 for the prophylaxis of embolism in VHF. Dabigatran is excreted approximately 80% by the kidney and is not metabolized via CYP3A4. In the EU, dabigatran is contraindicated in severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 ml/min).

The efficacy of dabigatran was tested in the RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy) trial involving 18,113 patients with VCF and at least one additional risk factor for stroke [17]. Patients were randomized into three study arms 1:1:1 with two blinded dabigatran doses (110 mg or 150 mg twice daily) and an open-label warfarin group (target INR 2.0-3.0). The average follow-up period was two years. Primary end points were cerebrovascular accident and systemic embolism, with blinded evaluation using the PROBE (prospective randomized open with blinded endpoint evaluation) method. The rate of primary endpoint events was 1.71% per year in the warfarin group, 1.54% per year in the dabigatran 2 x 110 mg group (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.74-1.10; p<0.001 for non-inferiority) and 1.11% per year in the dabigatran 2 x 150 mg group (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.52-0.81; p<0.001 for superiority). Major bleeding was significantly lower at 2.87% per year in the dabigatran 110-mg group than at 3.57% per year in the warfarin group (RR 0.80, 95%-CI 0.70-0.93; p=0.003) but comparable at 3.32% per year in the dabigatran 150-mg group (RR 0.93, 95%-CI 0.81-1.07; p=0.31). The rate of hemorrhagic stroke was higher with warfarin (0.38% per year) than with dabigatran 110 mg (0.12% per year, RR 0.31, 95%-CI 0.17-0.56; p<0.001) and also with dabigatran 150 mg (0.10% per year, RR 0.26, 95%-CI 0.14-0.49; p<0.001). A subgroup analysis for secondary prevention in patients with a history of TIA or stroke showed a comparable result to the main study [18].

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto

®

) is a direct Factor Xa inhibitor that has been approved in Europe by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) since 2008 for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in adult patients undergoing elective knee or hip replacement surgery. Since April 2012, it has also been approved in Switzerland for the prevention of stroke in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Rivaroxaban has dose-dependent pharmacokinetics. One-third is excreted unmetabolized in the urine and two-thirds metabolized in the liver, half of which is excreted hepatobiliary and half renal. Despite a relevant proportion of renal elimination, there is no contraindication in mild to moderate renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance 30-79 ml/min).

The effect of rivaroxaban (daily dose 20 mg or 15 mg at a creatinine clearance of 30-49 ml/min) was tested in the ROCKET-AF trial (Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Factor Xa Inhibitor Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation) in a double-blind, double-dummy design against warfarin in 14 264 patients [19]i.e., the patients each received a combination of the respective OAK and the complementary placebo incl. regular INR testing in a central laboratory with real or “dummy” values and the corresponding adjustment of medication. The endpoint of the study was also the occurrence of cerebral stroke or systemic embolism. In the per-protocol (PP) analysis, this endpoint was observed in 1.7% per year in the rivaroxaban group and 2.2% per year in the warfarin group (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0-66-0.96; p<0.001 for non-inferiority). Similarly, in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, rivaroxaban was shown to be noninferior to warfarin with 2.1% endpoint events per year compared with warfarin with 2.4% per year (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.75-1.03; p<0.001 for noninferiority and p = 0.12 for superiority). Intracranial (0.5 vs. 0.7% per year, HR 0.67, 95%-CI 0.47-0.93; p=0.02) and fatal bleeding (0.2 vs. 0.5% per year, HR 0.50, 95%-CI 0.31-0.79; p=0.003) occurred less frequently with rivaroxaban. A subgroup analysis in patients who had already suffered a stroke or TIA showed no differences in efficacy compared with patients without such a history, demonstrating comparable efficacy in both primary and secondary prevention of stroke [20].

Comparison of the new anticoagulants

All three new agents have demonstrated non-inferiority to warfarin in large randomized trials. Unfortunately, no study exists that directly compares the new substances. Thus, different advantages and disadvantages can be calculated in each study due to slightly different designs as well as different study populations, without the absolute numbers being comparable.

Currently, it is not possible to assess which substance has the greatest efficacy or the best benefit-risk ratio. An indication might be provided by the number-needed-to-treat (NNT = number of patients who must be treated to prevent 1 event), which is 625 for dabigatran 2 x 110 mg, 172 for dabigatran 2 x 150 mg, 303 for apixaban, and 200 for rivaroxaban. Thus, the high dose of dabigatran shows the highest efficacy in the prophylaxis of cerebral stroke, whereas apixaban shows the lowest bleeding rate. Of interest to neurologists is the fact that in the ROCKET-AF (rivaroxaban) trial, patients tended to be sicker and had a higher CHADS2 score (average: 3.5) than in the apixaban and dabigatran trials (each averaged about 2.0).

All agents have shown some common, substantial benefits compared with VKA: a) Fixed dosages regardless of age, sex and weight; (b) no interaction with food and few interactions with other drugs; c) No need for INR monitoring; (d) fewer or comparable bleeding risks and, in particular, a lower risk of intracerebral hemorrhage.

Open questions

Coagulation control and thrombolysis under the new OAKs.

A major challenge arises with regard to the new substances in the situation of acute cerebral stroke and the question of acute therapy. While the current coagulation situation of VKA can be determined quickly and easily, even with handheld devices, via the INR, this possibility does not currently exist for the new substances. However, urine tests to detect the metabolites of dabigatran and rivaroxaban in urine are currently under development [21]. For dabigatran, there is evidence that normal values for thrombin time (TT), activated partial thrombin time (aPTT), or “escarin clotting time” indicate a normal coagulation situation [22]. With rivaroxaban and apixaban, compound-specific factor Xa activity can be measured. There seems to be a general consensus that ingestion of any of the new agents within the previous 48 hours is an absolute contraindication to thrombolysis.

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Another problem arises in the situation of hemorrhage, especially in the context of a feared intracerebral hemorrhage. No specific antidote exists for any of the new substances. However, what they all have in common is, on the one hand, their short plasma half-life and the fact that they inhibit only one specific factor of the coagulation cascade and not the extensive production of diverse coagulation factors as VKA do. In the various clinical trials, the administration of clotting factors has mostly been recommended, based in part on findings from preclinical bleeding models.

Compliance

Until now, patients with VCF have been closely linked to their primary care physician or treating physician by the need for frequent INR checks. This binding is eliminated by the fixed dosage of the new substances. Only time will tell what impact this will have on patients in general, and in particular on their compliance with their medications in the absence of laboratory evidence that they are taking them regularly.

Conclusion

After 60 years of monopoly of vitamin K antagonists for primary and secondary prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation, new substances have now provided evidence of efficacy. Even though the new substances show clear advantages over VKA (fixed dosage, no coagulation controls, fewer interactions with food and other drugs), none of the substances currently shows a clear advantage over the competitors.

Which patients (continue to) receive VKA?

There is no indication to switch patients who have been stable for years on VKA therapy and, in particular, have stable INR values within the therapeutic range to one of the new substances. Such patients were also not included in the studies. Also, therapy with VKA will continue to be necessary in patients with severe renal insufficiency or patients who require therapy with a drug that interacts with the new OAKs (e.g., ketoconazole) or who have another indication for VKA (e.g., mechanical heart valve replacement).

Which patients are candidates for the new OAK?

The trial data presented here relate exclusively to primary and secondary prevention in VHF. For some substances, strictly defined additional indications exist. From today’s point of view, ideal candidates for the new substances are patients with VHF whose adjustment to a therapeutic INR proves to be difficult with VKA, or who do not wish to have regular blood samples taken, or who find it difficult to do so (e.g. long distance to the nearest physician). Whether patients in secondary prevention after stroke or TIA benefit from the higher efficacy is not clear from the current studies. Patients with an increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage could also be candidates for the new substances, although here, too, no clear answer can be given on the basis of the current study situation.

David Seiffge

Literature:

- Fuster V, et al: 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in partnership with the European Society of Cardiology and in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:101-198.

- Wolf PA, et al: Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991;22:983-988.

- The Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for Atrial Fibrillation Investigators.The effect of low-dose warfarin on the risk of stroke in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1505-1511.

- Ezekowitz MD, et al: Warfarin in the prevention of stroke associated with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. Veterans Affairs Stroke Prevention in Nonrheumatic Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1406-1412.

- Hart RG, et al: Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:857-867.

- Aguilar MI, et al: Oral anticoagulants versus antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Re 2007;CD006186.

- Ogilvie IM, et al: Underuse of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med 2010;123:638-645 e4.

- Limdi NA et Veenstra D L.: Warfarin pharmacogenetics. Pharmacotherapy 2008;28:1084–1097.

- Mahajan P, et al: Clinical applications of pharmacogenomics guided warfarin dosing. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:10-19.

- Mega JL: A new era for anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365 1052-1054.

- Diener HC, et al: The king is dead (warfarin): direct thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors: the next Diadochian War? Int J Stroke 2012;7:139-141.

- Diener HC, et al: Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: do we still need warfarin? Curr Opin Neurol 2012;25:27-35.

- Shantsila E et Lip GY: Apixaban, an oral, direct inhibitor of activated factor Xa. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2008;9:1020-1033.

- Granger CB, et al: Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:981-992.

- Lopes RD, et al: Apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboemboLic events in atrial fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial: design and rationale. Am Heart J 2010;159:331-339.

- Connolly SJ, et al: Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:806-817.

- Connolly SJ, et al: Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139-1151.

- Diener HC, et al: Dabigatran compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous transient ischaemic attack or stroke: a subgroup analysis of the RE-LY trial. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:1157-1163.

- Patel MR, et al: Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;36:883-891.

- Hankey GJ, et al: Rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack: a subgroup analysis of ROCKET AF. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:315-322.

- Harenberg J et Kraemer R: Measurement of the new anticoagulants. Thromb Res, 2012;129 Suppl 1:S106-S113.

- Van Ryn J, et al: Dabigatran etexilate – a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost 2010;103:1116-1127.

CARDIOVASC 2013; no. 1: 22-26.