Before initiating therapy, GIST patients should be discussed at an interdisciplinary tumor board. For intermediate to high risk of relapse, adjuvant imatinib therapy should be considered after resection. Patients with metastatic GIST benefit from tyrosine kinase inhibitors and local measures.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is a mesenchymal tumor entity of the gastrointestinal tract or, much less commonly, of the intra-abdominal soft tissue. The so-called Cajal cells are assumed to be the cells of origin. These specialized muscle cells are located in the mesenteric plexus and have a pacemaker function with regard to peristaltic contraction. GISTs can occur along the entire gastrointestinal tract – but are most commonly found in the stomach (50%) and small intestine (30-35%), and much less commonly in the colon/rectum (5%) or esophagus (<1%). GISTs arising in the omentum, mesentery, or retroperitoneally are referred to as E-GISTs (extra-gastrointestinal) and are a rarity.

The annual incidence of GIST is reported in the literature to be approximately ten cases per million population. If one also includes the so-called micro-GIST (GIST tumor <1 cm), which are found autoptically in patients over 50 years of age in up to 20% in the area of the stomach/gastroesophageal junction, it is much higher. However, micro-GISTs have an extremely low malignancy potential and therefore represent a separate, clinically irrelevant subgroup.

Diagnosis and staging

The majority of patients diagnosed with GIST are symptomatic of the tumor disease. Classically, they report gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or bowel irregularities. However, due to the increased use of imaging in the context of other issues, GIST is detected in up to 25% of cases in completely asymptomatic patients.

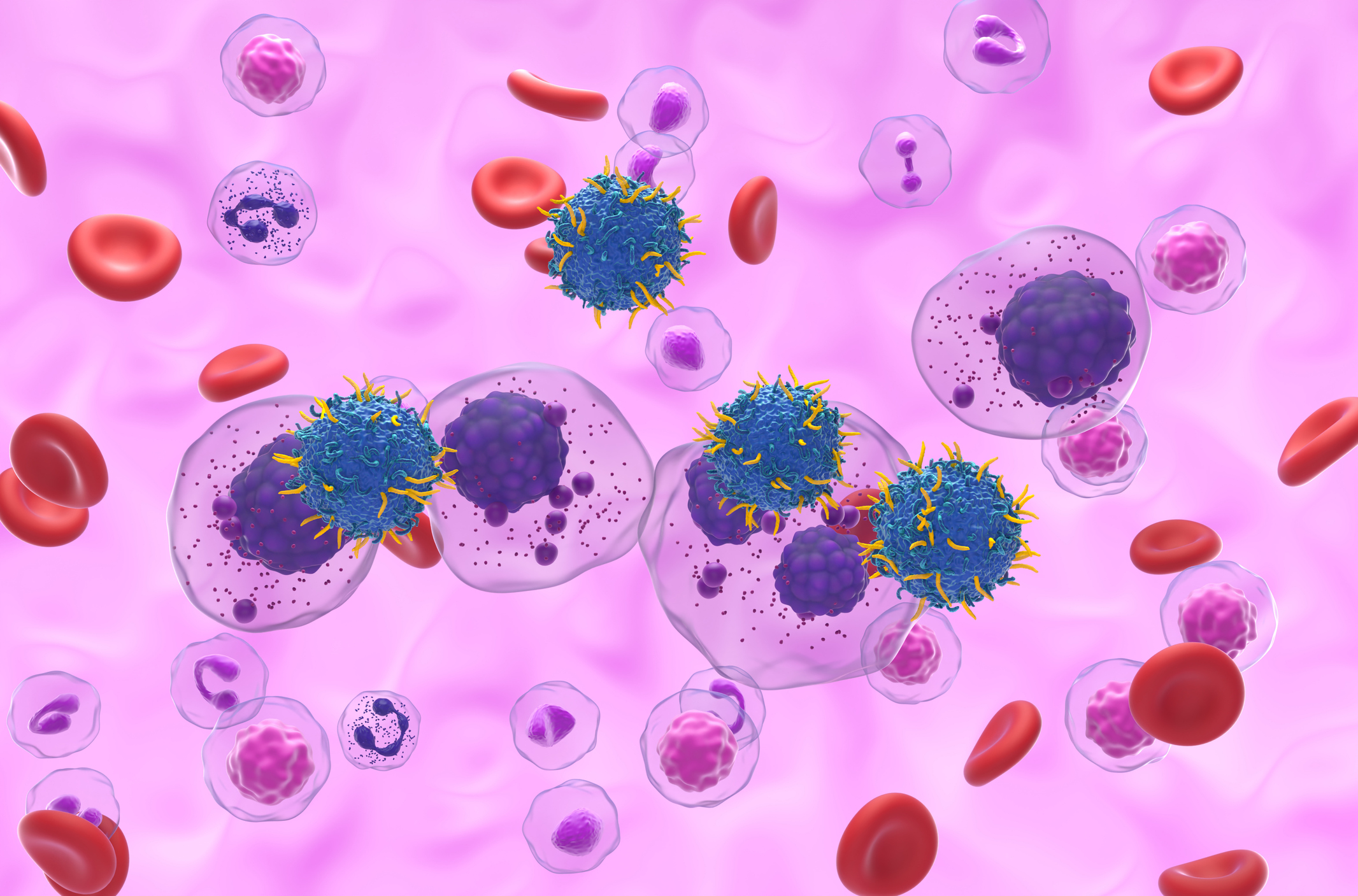

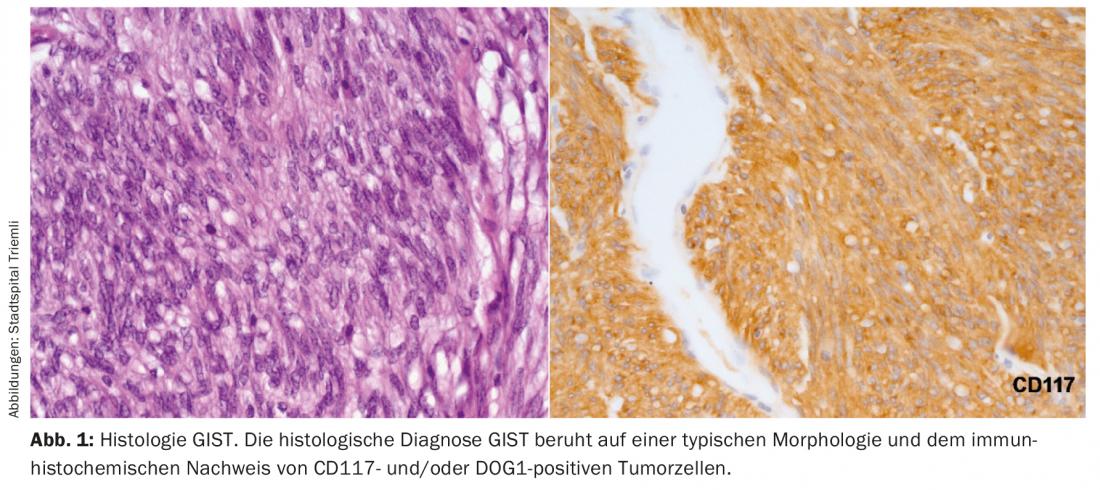

The diagnosis of GIST can ultimately only be made on the basis of typical histology. Histologically, an endoscopically obtained biopsy is clearly preferable to a percutaneous biopsy. Positivity for CD117 and DOG1 distinguishes a GIST from other mesenchymal tumors or a mesenchymal growing carcinoma or melanoma (Fig. 1).

Metastases from GIST typically develop in the liver, omentum, or peritoneum. Metastases outside the abdomen are seen only in advanced disease that has already been intensively treated. Therefore, at least a contrast-enhanced CT abdomen/pelvis or MRI abdomen should be performed as initial staging examination.

Molecular Pathology

75% of GIST patients have a mutation of the c-Kit gene, typically in exon 11 or 9. The second most common molecular alteration (10%) is found to be a mutation in the PDGFR gene region. All these changes lead to a continuous activation of the cells. If neither a c-KIT nor a PDGFR mutation can be detected, the disease is referred to as wild-type GIST, although its definition is currently in flux. However, changes in the BRAF, RAS and SDH-A-D genes are then frequently found. Wild-type GIST are typically seen in association with neurofibromatosis, Carney triad, or Carney-Stratakis syndrome.

Localized non-metastatic GIST.

Localized, nonmetastatic GIST should be resected whenever possible. Complete resection represents the only curative therapy.

Tumors <2 cm can alternatively be monitored endosonographically and resected only when size progression occurs.

Resection

The ultimate goal of surgical curative resection of a GIST is to achieve an R0 situation (no macroscopic or microscopic tumor remnants at the incision margin). R0 resection is usually achieved when a 1-2 cm safety distance from the tumor is maintained. The extent of surgical intervention is highly dependent on the size and location of the GIST. A small to medium-sized GIST in the body of the stomach can often be removed with a simple laparoscopic partial gastric resection. However, if the GIST is located in the duodenum, for example, the extent of resection may need to be extended to a Whippel duodenopancreatectomy. Unlike most other malignant tumors of the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors), resection of GIST does not require locoregional lymph node dissection because of the rarity of lymph node metastases (prevalence <1%). Only in the rare pediatric GIST or in young adults (<40 years) is the risk of lymph node metastasis significantly higher (20-59%), which may obviously influence surgical tactics. Generally, laparoscopic resection is sought whenever possible due to faster recovery. However, in the course of resection, rupture of the tumor capsule must not occur under any circumstances, as otherwise peritoneal seeding of tumor cells will occur, usually resulting in a palliative tumor situation. Large GISTs in particular often have a very soft and fragile capsule that can rupture rapidly if not handled carefully (laparoscopically). Therefore, the advantages of laparoscopic resection should always be well weighed against the risks of rupture of the tumor during “high-end acrobatic laparoscopy,” especially in large tumors.

Adjuvant therapy

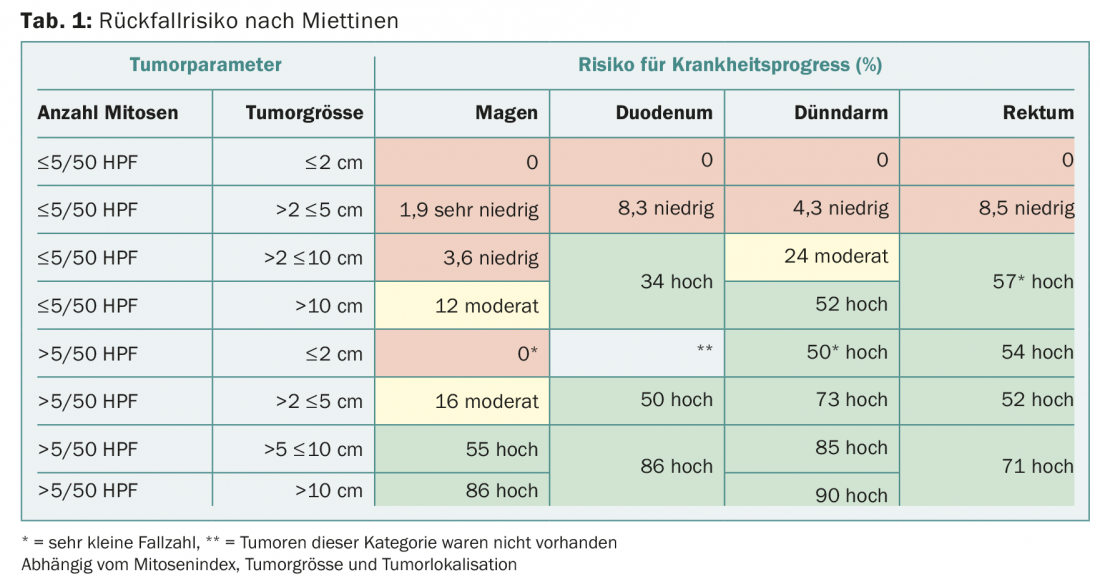

Despite successful R0 resection, patients may develop metastases over time. The risk of developing metastases depends primarily on the mitotic index, tumor size, and localization in the gastrointestinal tract – these factors are captured in the so-called Miettinen index (Table 1) [1]. The relapse tables developed by Heikki Joensuu [2] are more finely graded and therefore better reflect the individual risk of relapse. All studies that investigated the benefit of adjuvant therapy used the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib. The inclusion criteria as well as the duration of therapy varied from study to study. Based on data from the SSGXVIII/AIO trial [3], which showed a survival benefit of three years vs. one year of imatinib therapy, a therapy duration of three years is nowadays recommended. Whether or not a longer duration of therapy (totally five or six years) is useful is nowadays being investigated in studies. While the SSGXVIII/AIO trial only included patients with “high risk” criteria – based on the modified NIH consensus applied at that time – nowadays patients with a moderate to high risk of relapse are offered adjuvant therapy according to Miettinen. Especially in moderate-risk patients, it is important to discuss the benefits versus the side effects (such as mucositis, muscle cramps, nausea). In contrast to the studies, a mutation analysis is now recommended by the majority at the start of therapy. If an imatinib-insensitive mutation, e.g. PDGFR D842V, is present, such an expensive and also burdensome therapy does not make sense. Whether patients with an exon 9 mutation will also benefit from a higher imatinib dose (800 mg/d) in an adjuvant setting, in analogy to the data from the palliative setting, is currently unclear. However, experience has shown that a dose of 800 mg/d cannot be continued for a prolonged period of time due to the associated toxicity.

Neoadjuvant therapy

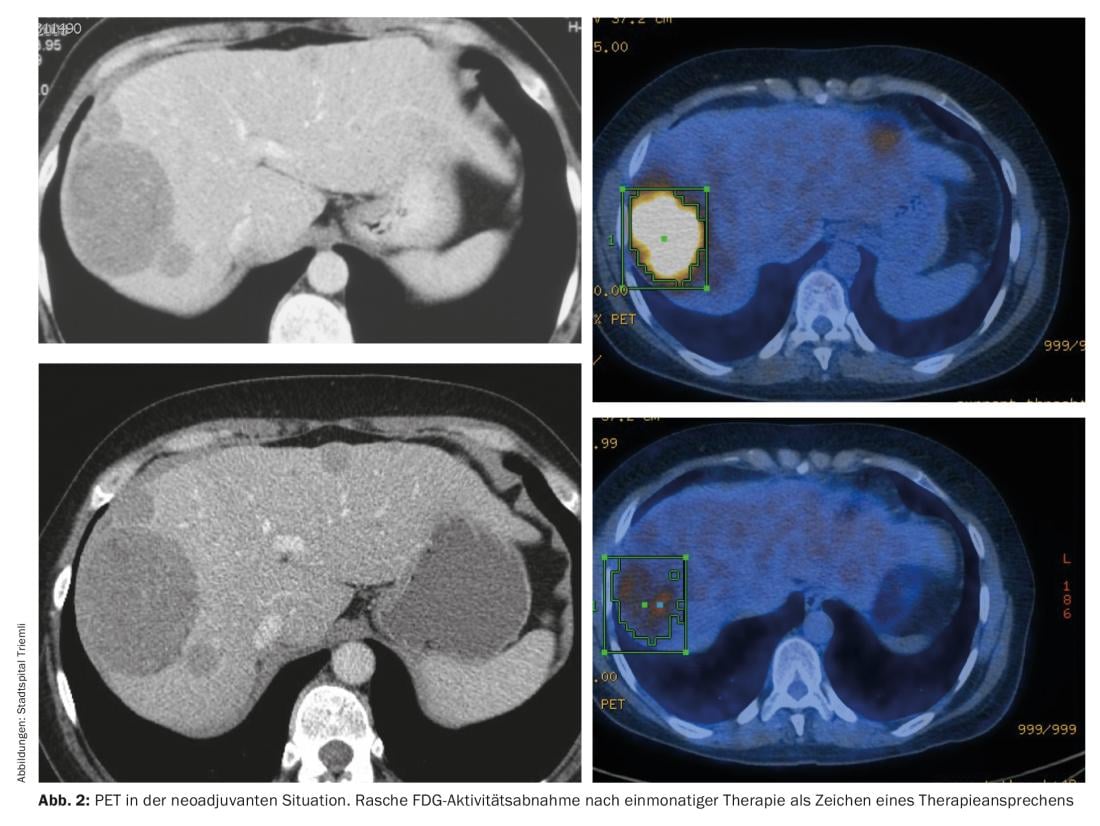

For locally advanced tumors, the option of neoadjuvant therapy should always be discussed at the interdisciplinary tumor board-especially if mutilating surgery is necessary for complete resection. Prerequisites for neoadjuvant therapy are a histologically verified diagnosis of GIST and the presence of an imatinib-sensitive mutation. Close imaging is recommended to prevent unwanted progression. PET can be used to make a statement regarding response as early as one month after the start of therapy (Fig. 2).

The optimal neoadjuvant duration of therapy is unclear, but the majority of literature suggests six to nine months [4].

Aftercare

Following surgery, as well as during and after adjuvant therapy, regular clinical examinations and imaging are recommended. Unfortunately, an evidence-based follow-up regimen does not exist. During the first two years after surgery or after suspension of adjuvant therapy, we perform abdominal imaging three to six months – at times of lower risk of relapse (during ongoing adjuvant therapy; three to five years after surgery or after suspended imatinib therapy) only every six to twelve months. Because of serial imaging and the associated radiation exposure, MRI is preferable to CT, especially in young patients.

Metastatic, non-resectable GIST.

Drug therapy: Thanks to TKI use, the prognosis of patients with metastatic GIST has improved significantly from an average of ten months to approximately 55 months. If an imatinib-sensitive mutation is present, imatinib 400 mg/d is the first-line therapy of choice. In patients with an exon 9 mutation, based on the meta-GIST data [5], a primary recommended dosage of 800 mg/d is recommended. In case of progression, the TKIs sunitinib [6] and regorafenib [7], which have been investigated in phase III trials, are available. Often, patients remain in good general health after progressing through all three established lines of therapy (imatinib, sunitinib, regorafenib), so one would like to offer them effective therapy. Unless they can be enrolled in a trial, a re-challenge with imatinib certainly makes sense, even though the PFS benefit was very limited compared to placebo in the RIGHT trial. Mechanistically, it is thought that imatinib-sensitive clones resistant to prior TKIs gained the upper hand under prior TKI therapies. Although this effect was studied only for imatinib, it can probably be extrapolated to the other TKIs.

Other TKIs such as pazopanib [8] or ponatinib [9] have only been compared with “best supportive care” in phase II trials. They resulted in a significant but unfortunately very limited prolongation of PFS. Primarily, they caused disease stabilization. Unfortunately, a clear response in the sense of a partial or complete response was rarely seen. Researchers are therefore pinning their hopes on other substances such as cabozantinib or the checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab.

A completely different but very interesting study approach is to treat GIST patients with conventional cytostatics such as doxorubicin or paclitaxel after years of TKI therapy. The hope is that previously chemotherapy-resistant GIST has been altered by prolonged TKI therapy such that it is now chemotherapy-sensitive.

Even though the TKIs imatinib, sunitinib and regorafenib are so-called “targeted therapies”, unfortunately relatively considerable toxicities occur over time. Under sunitinib, 20% of patients developed grade III toxicity (primarily fatigue, hand-foot syndrome), and under regorafenib up to 60% (hypertension, hand-foot syndrome). To counteract these side effects at an early stage, regular evaluation by a physician or nurse is necessary. Similarly, patients should be made aware of the problem of medication compliance as well as interactions.

Whenever a patient with GIST disease is on systemic therapy, the therapeutic response should be assessed clinically as well as radiologically at regular intervals. While radiology colleagues use RECIST criteria for therapy assessment in the vast majority of tumor entities, Choi criteria will be used for GIST patients. These also allow tumor density to be included in the assessment and thus better reflect the biological behavior of the GIST [10].

Non-drug therapy: if a patient shows progression, interdisciplinary evaluation is appropriate. Thus, surgical options are fully utilized in addition to drug options. Especially if there is focal progression and development of resistance of individual metastases to drug therapy, resection of these therapy-resistant metastases should also be discussed. For localization of focal progression, FDG-PET computed tomography is a useful diagnostic tool. Resection of these focally refractory metastases may prevent further drug escalation in some patients. Otherwise, surgical resection of metastases is indicated only for symptomatic complications (pain, bowel obstruction, or gastrointestinal bleeding). As an alternative to palliative surgical resection of single metastases, the use of other locally ablative methods such as stereotactic radiotherapy or radiofrequency resp. Microwave ablation should be considered.

Take-Home Messages

- Patients diagnosed with GIST should always be discussed at an interdisciplinary tumor board before initiating therapy.

- For GIST with intermediate to high risk of recurrence, adjuvant imatinib therapy should be evaluated with the patient after successful resection.

- Patients with metastatic GIST benefit not only from the tyrosine kinase inhibitors imatinib, sunitinib, and regorafenib, which are approved in Switzerland and are covered by health insurance, but also from local measures, whether surgery, RFA, or radiotherapy.

Literature:

- Miettinen M, et al: Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology 2006; 23: 70-83.

- Joensuu H, et al: Lancet Oncology 2012; 13: 265-274.

- Joensuu H, et al: JAMA 2012; 307(12): 1265-1272.

- Rutkowski P, et al: Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20: 2937-2943.

- Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Meta-Analysis Group: JCO 2010; 28: 1247-1253.

- Demetri G, et al: Lancet 2006; 368: 1329-1338.

- Demetri G, et al: Lancet 2013; 381: 295-302.

- Mir O, et al: Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 632-641.

- Heinrich M, et al: J Clin Oncol 2015; abstract 10535.

- Benjamin RS, et al: J Clin Oncol 2007; 25(13): 1760-1764.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(3): 24-28.