After an acute myocardial infarction, postinfarction management is the focus of treatment. To prevent another coronary event, it is essential to identify and treat appropriate risk factors. Non-drug interventions have their place, as do the “big five” of secondary prevention.

The prognosis of a heart attack has improved significantly in recent years. Whereas 30% died in hospital until the 1960s, monitoring in intensive care units, lysis therapy, and ultimately acute PTCA reduced the mortality rate to 5%. However, mortality until hospital admission is still 35-40%, cautioned Dr. med. Gregor Fahrni, Basel. For this reason, postinfarction treatment must begin with the heart attack. The milestone that can reduce mortality is monitoring with the possibility of defibrillation. This should be maintained until arrival at the hospital. To improve symptomatology and control pain, 2 mg of morphine can be administered iv. Oxygen should be given if oxygen saturation is below 90%. Nitroglycerin, on the other hand, should be avoided because the vessel is not opened in STEMI. In contrast, in patients with right myocardial infarction, prognosis may be worsened by increases in vasodilation, cardiogenic shock, or decreases in preloading. The administration of beta-blockers or NOAKs also do not have good evidence in this setting.

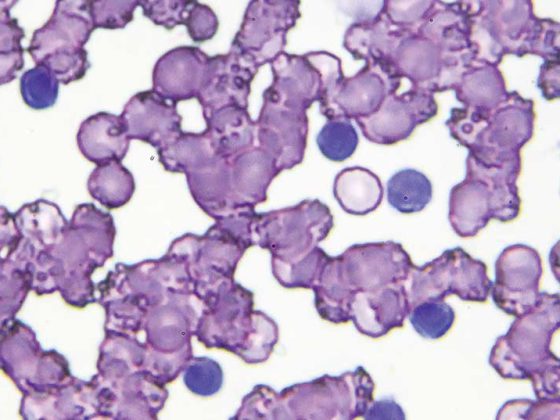

Nomenclature of myocardial infarction

Classic myocardial infarction is divided into type 1 and type 2, as measured by the rise or fall of troponin levels in combination with symptoms of ischemia or ECG changes. Type 1 myocardial infarction corresponds to acute coronary syndrome. There is an underlying plaque rupture leading to partial occlusion of the vessel. Usually, this “classic myocardial infarction” presents as an NSTEMI. If the vessel is completely occluded, ECG may demonstrate STEMI. In type 2 myocardial infarction, there is a mismatch in oxygen supply and its demand. They usually present in combination with severe anemia, hypotension, hypertensive derailment, tachyarrhythmia, or coronary spasm. In these cases, postinfarction management does nothing. A 6-8% proportion of all myocardial infarctions are attributed to MINOCA. This corresponds to a classic myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries. Causes range from plaque erosion without stenosis to thromboembolism to spontaneous dissection.

The Big Five of Secondary Prevention

The Big Five of secondary prevention have one thing in common: they have proven to guarantee a prolonged life and reduce the risk of a new heart attack. These include aspirin, statins, beta blockers, ACE inhibitors, and P2Y12 antagonists. Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was originally used to treat stent thrombosis. Due to improvements in stents, this is now almost a thing of the past. Nevertheless, DAPT continues to be used – now for therapy of ischemic events, Fahrni said. The great art is to hit the narrow therapeutic window. This is because the risk of bleeding increases with increasing active anticoagulation, whereas secondary ischemic events are prevented. And vice versa: If clotting is inhibited less, the risk of bleeding remains low, but the risk of a second infarction increases. Accordingly, bleeding risk and ischemia risk must be weighed against each other.

Statins can be given indefinitely in all patients regardless of cholesterol level. The LDL target value is <1.4 mmol/l. If this is not achieved after four to six weeks, ezetimibe and/or a PCSK9 inhibitor should be added. ACE inhibitors can also be administered at maximum dose in all patients. The focus is primarily on patients with diabetes mellitus or renal insufficiency. For beta-blockers, the maximum tolerated dose should also be aimed for. Any patient can also benefit from them, especially in cases of incomplete revascularization.

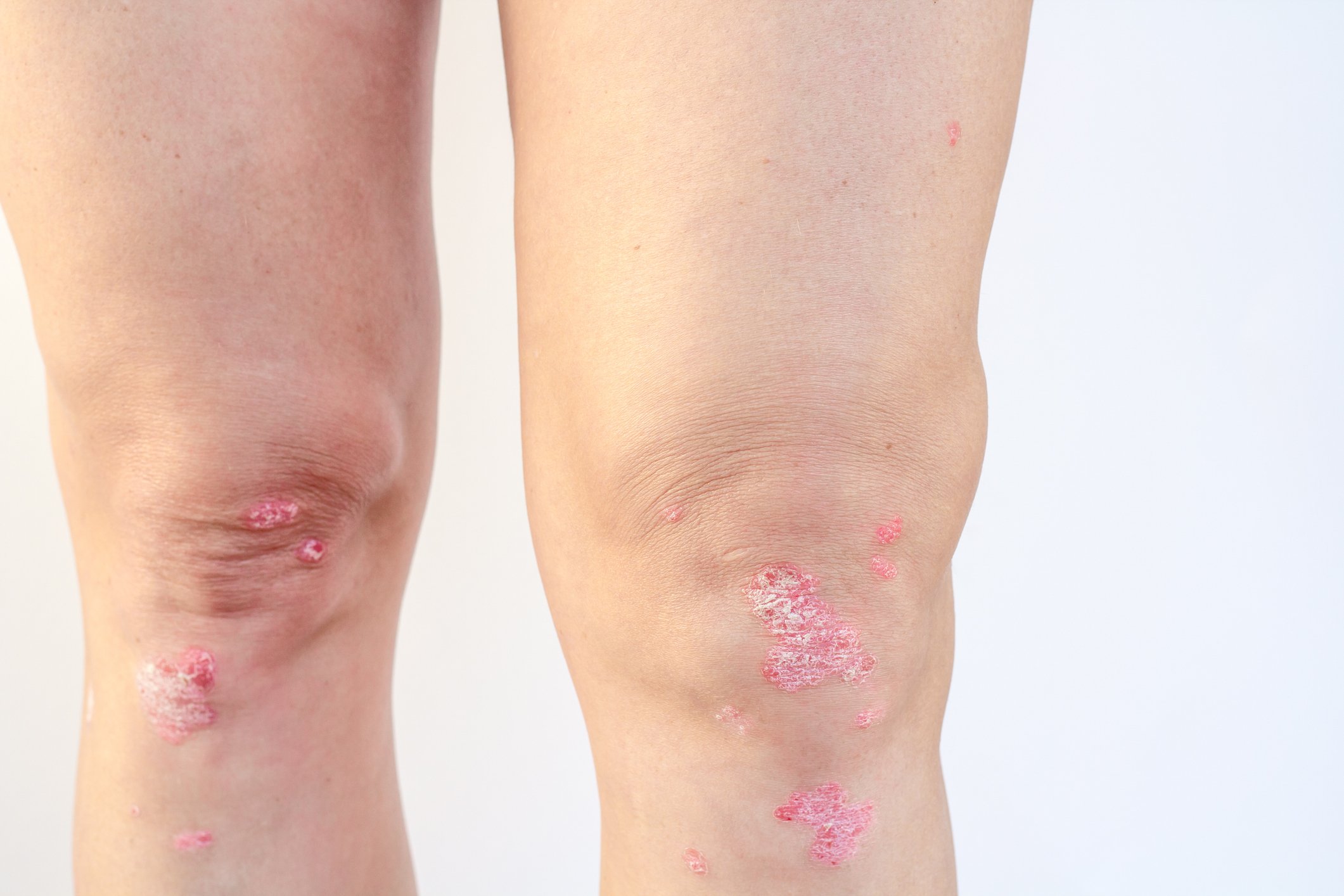

Smoking harms health

Nonpharmacologic interventions primarily include smoking cessation. Studies have shown that the risk of a reoccurrence can be reduced by 36% just by giving up cigarettes. Also of enormous importance is rehabilitation after heart attack. Not only can the quality of life be massively improved. Similarly, mortality risk can be significantly reduced by 13%, cardiovascular mortality by 26%, and rehospitalization by 31%.

Source: Forum for Continuing Medical Education

CARDIOVASC 2021; 20(1): 29 (published 2/3/21, ahead of print).