The treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has made significant progress in recent years, but therapy remains a challenge for many patients: up to 60 % of those affected either do not respond to initial treatment or lose their response to therapy over time [2]. TNF inhibitors (TNFi) are still often routinely used as first-line therapies after conventional synthetic (cs)DMARDs and, if there is an insufficient response switched to a second TNFi, which is referred to as TNFi cycling [3]. Current data now suggest that this practice should be reconsidered: instead of another TNFi cycle, switching to substances with a different mechanism of action, such as Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi), could be beneficial for patients [1].

In the current treat-to-target (T2T) recommendations for RA, clinical remission is the primary treatment goal [4]. Remission is of central importance for patients, as it not only slows down the progression of joint damage, but also significantly improves the psychological well-being and physical functioning of those affected [5-7]. Early remission in particular is crucial for the long-term effects of the disease [8-10]. Study data andpatient-reported outcomes (PRO) show that early remission is associated with long-term remission [8, 9]. Nevertheless, around 30 to 40 % of RA patients who initiate first-line therapy with TNFi discontinue treatment due to primary failure, secondary lack of response or intolerance [1]. In these cases, it is particularly important to quickly switch to an alternative therapy together in order to maintain the chance of a lasting remission and not lose disease control.

Cycling vs. switching

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommends switching to a bDMARD or tsDMARD of a different drug class in RA after failure of an initial biologic or target-specific therapeutic agent (bDMARD or tsDMARD), while the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommends switching to a different mechanism of action and cycling [4, 11]. Both TNFi cycling and switching to an alternative mechanism of action are frequently used when TNFi therapy fails [12]. However, study data show that patients who undergo multiple TNFi cycles are more likely to fail therapy and switch again [13]. However, switching to a different mechanism of action would be associated with an increased chance of clinical improvement and a lower dropout rate [14,15].

Upadacitinib advantageous for switching

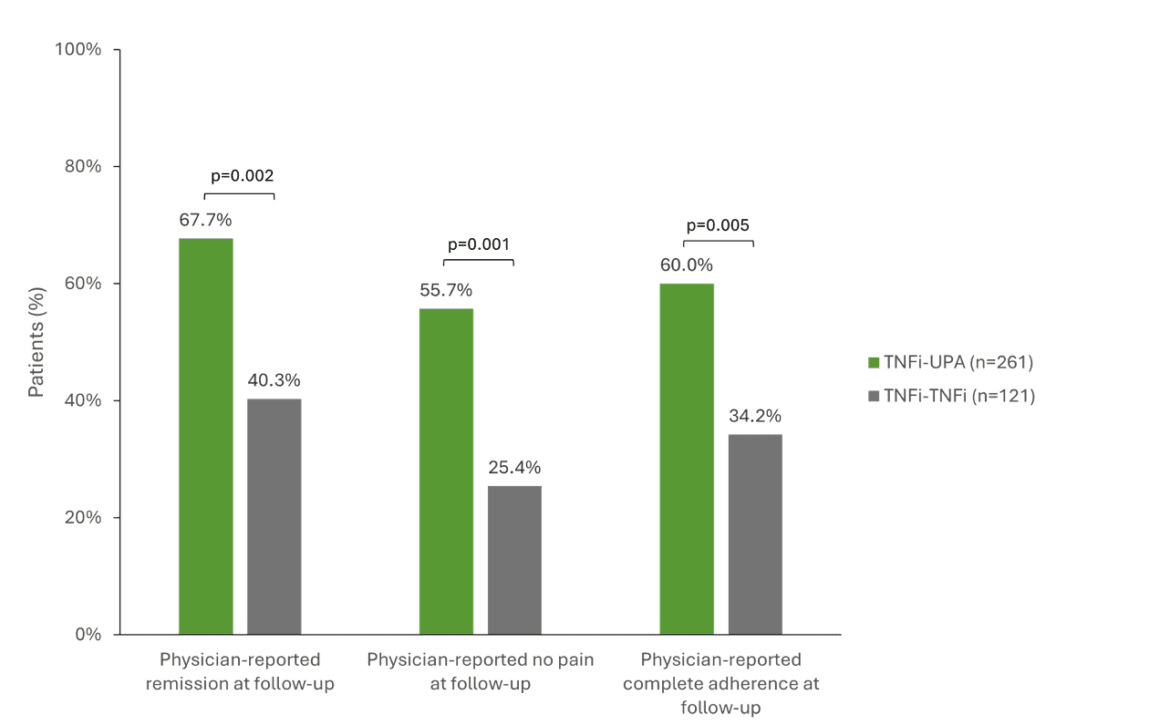

A multinational study that analyzed registry data of 503 RA patients after failure of first-line TNFi therapy investigated the success of different follow-up therapies [1]. Patients were compared with a switch to the JAKi upadacitinib (RINVOQ®, UPA, n=261), a second TNFi (n=128) or a DMARD with a different mechanism of action (n=114) [1, 16]. Patients who switched from a TNFi to UPA achieved significantly better clinical outcomes than those who received a second TNFi. For example, 67.7% of UPA patients achieved remission compared to 40.3% of those who received a second TNFi (p=0.002). Freedom from pain was higher with UPA (55.7 % vs. 25.4 %, p=0.001) and adherence was 60 % compared to 34.2 % among TNFi patients (p=0.005) (Fig. 1) [1]. UPA was also superior to a DMARD with a different mechanism of action in all three respects. In addition, the recently published 5-year data from the SELECT-COMPARE study underline that a change of mechanism of action appears to be beneficial for RA patients who did not reach their treatment goal and that this benefit can be maintained in the long term [17]. The study showed numerical differences mainly in favor of patients who switched from ADA to UPA [17]. However, not only in RA, but also in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), study data indicate that patients respond less well to a second or third TNFi than to the first [12, 18, 19].

Upadacitinib also beneficial as first-line therapy after csDMARDs

The efficacy of UPA versus TNFi as first-line therapy was compared in the head-to-head studies of the SELECT-COMPARE program [20, 21]. UPA + methotrexate (MTX) showed significantly higher efficacy than adalimumab (ADA) + MTX in various parameters such as DAS28≤2.6, ACR50, change in HAQ-DI and pain relief from as early as 12 weeks [20, 21]. It was also possible to demonstrate a sustained higher remission with UPA + MTX compared to ADA + MTX over 5 years [21]. Several real-world studies have now also demonstrated the good efficacy and long treatment duration of upadacitinib in daily practice [22, 23]. In addition, the up to 7.5-year data published at EULAR 2024 confirm the known safety profile of UPA in over 4700 patients [24].

Fig. 1: Significantly better clinical results when switching to UPA (TNFi-UPA) compared to a second TNFi (TNFi-TNFi). TNFi = TNF inhibitor, UPA = upadacitinib. Adapted from [1].

Conclusion

The available data suggest that switching from TNFi to UPA may be a beneficial treatment option for RA patients who have not responded adequately to or are intolerant of initial TNFi therapy [1]. Compared to TNFi cycling, switching to UPA with an alternative mechanism of action offers better chances of remission, freedom from pain and treatment adherence [1]. These findings support the recommendation to switch to an alternative mechanism of action at an early stage in order to improve long-term treatment outcomes for RA patients and increase the chance of a lasting remission.

Abbreviations: ACR = American College of Rheumatology; ACR50 = ACR response with ≥50% improvement; ADA = adalimumab; axSpA = axial spondyloarthritis; csDMARD = conventional synthetic DMARD; DAS28 = Disease Activity Score 28; DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; EULAR = European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology; HAQ-DI = Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; JAK = Janus kinase; JAKi = JAK inhibitor; MTX = methotrexate; PRO = patient-reported outcome; PsA = psoriatic arthritis; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; T2T = treat-to-target; TNF = tumor necrosis factor; TNFi = TNF inhibitor; UPA = upadacitinib.

Brief technical information RINVOQ®

This article was produced with the financial support of AbbVie AG, Alte Steinhauserstrasse 14, 6330 Cham.

This article has been released in German.

Text: Dr. sc. nat. Stefanie Jovanovic

CH-RNQ-240019 11/2024

Literature

1 Caporali, R., et al, A Real-World Comparison of Clinical Effectiveness in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Treated with Upadacitinib, Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors, and Other Advanced Therapies After Switching from an Initial Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitor. Adv Ther, 2024. 41(9): p. 3706-3721.

2 Vallejo-Yague, E., et al, Comparative effectiveness of biologics in patients with rheumatoid arthritis stratified by body mass index: a cohort study in a Swiss registry. BMJ Open, 2024. 14(2): p. e074864.

3 Edgerton, C., et al, Real-World Treatment and Care Patterns in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis Initiating First-Line Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitor Therapy in the United States. ACR Open Rheumatol, 2024. 6(4): p. 179-188.

4 Smolen, J.S., et al, EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis, 2023. 82(1): p. 3-18.

5 Lillegraven, S., et al, Remission and radiographic outcome in rheumatoid arthritis: application of the 2011 ACR/EULAR remission criteria in an observational cohort. Ann Rheum Dis, 2012. 71(5): p. 681-6.

6 McInnes, I.B. and G. Schett, The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med, 2011. 365(23): p. 2205-19.

7 Einarsson, J.T., et al, Sustained Remission Improves Physical Function in Patients with Established Rheumatoid Arthritis, and Should Be a Treatment Goal: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study from Southern Sweden. J Rheumatol, 2016. 43(6): p. 1017-23.

8. Ten Klooster, P.M., et al, Long-term clinical, functional, and cost outcomes for early rheumatoid arthritis patients who did or did not achieve early remission in a real-world treat-to-target strategy. Clin Rheumatol, 2019. 38(10): p. 2727-2736.

9 Xie, W., J. Li, and Z. Zhang, The impact of different criteria sets on early remission and identifying its predictors in rheumatoid arthritis: results from an observational cohort (2009-2018). Clin Rheumatol, 2020. 39(2): p. 381-389.

10 Snoeck Henkemans, S.V.J., et al, Patient-reported outcomes and radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in sustained remission versus low disease activity. RMD Open, 2024. 10(1).

11 Fraenkel, L., et al, 2021 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2021. 73(7): p. 924-939.

12 Bogas, P., et al, Comparison of long-term efficacy between biological agents following tumor necrosis factor inhibitor failure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective cohort study. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis, 2021. 13: p. 1759720×211060910.

13 Wei, W., et al, Treatment Persistence and Clinical Outcomes of Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitor Cycling or Switching to a New Mechanism of Action Therapy: Real-world Observational Study of Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients in the United States with Prior Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitor Therapy. Adv Ther, 2017. 34(8): p. 1936-1952.

14 Migliore, A., et al, Cycling of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors versus switching to different mechanism of action therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis, 2021. 13: p. 1759720×211002682.

15 Mann, H., et al, Switching to a Targeted Drug with a Different Mode of Action After Discontinuation of the First TNF Inhibitor Is Associated with Better Drug Survival Compared to a Second TNF Inhibitor in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Propensity Score-matched Analysis from the Czech ATTRA Registry. Abstract 2277, presented at the ACR Convergence, November 14-19, 2024, Washington DC, USA.

16. current technical information for RINVOQ® (upadacitinib) at www.swissmedicinfo.ch.

17 Fleischmann, R., et al, Long-term Efficacy and Safety Following Switch Between Upadacitinib and Adalimumab in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: 5-Year Data from SELECT-COMPARE. Rheumatol Ther, 2024. 11(3): p. 599-615.

18 Linde, L., et al, Second and third TNF inhibitors in European patients with axial spondyloarthritis: effectiveness and impact of the reason for switching. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2024. 63(7): p. 1882-1892.

19 Ørnbjerg, L.M., et al, Drug effectiveness of 2nd and 3rd TNF inhibitors in psoriatic arthritis – relationship with the reason for withdrawal from the previous treatment. Joint Bone Spine, 2024. 91(4): p. 105729.

20 Fleischmann, R., et al, Upadacitinib Versus Placebo or Adalimumab in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis and an Inadequate Response to Methotrexate: Results of a Phase III, Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2019. 71(11): p. 1788-1800.

21 Fleischmann, R., et al, Long-term safety and efficacy of upadacitinib versus adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: 5-year data from the phase 3, randomized SELECT-COMPARE study. RMD Open, 2024. 10(2).

22 Witte, T., et al, The impact of C-reactive protein levels on the effectiveness of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a 12-month prospective, non-interventional German study. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 2024. 42(3): p. 726-735.

23 Bessette, L., et al, Real-World Effectiveness of Upadacitinib for Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis in Canadian Patients: Interim Results from the Prospective Observational CLOSE-UP Study. Rheumatol Ther, 2024. 11(3): p. 563-582.

24 Burmester GR, et al, Safety of Upadacitinib Across Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriatic Arthritis, and Axial Spondyloarthritis Encompassing 15,000 Patient-Years of Clinical Trial Data. Presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology (EULAR), June 12-15, 2024, Vienna, Austria. POS0894.

The references can be requested by professionals at medinfo.ch@abbvie.com.