Syringomyelia is a rare disease that develops due to a disturbance of cerebrospinal fluid flow (CSF) and is often due to obstruction of the subarachnoid space of the spinal column. Although syringomyelia is mainly manifested by sensory symptoms such as pain and insensitivity to temperature, in most cases it is discovered incidentally.

Syringomyelia is a disorder characterized by abnormal circulation of cerebrospinal fluid, leading to the formation of fluid-filled cavities (syringes) in the spinal cord parenchyma or central canal, write authors from the USA and India [1]. In up to 80% of those affected, the disease is congenital, with part of the cerebellum slipping downwards towards the spinal canal and thus pressing on the canal.

Syringomyelia is often associated with Chiari malformation type 1 (CM-1), but can also be caused by various factors such as spinal cord tumors, trauma or infectious adhesive arachnoiditis. The rare disease is now being diagnosed more frequently as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is increasingly used in the routine investigation of back and neck pain. The clinical course usually progresses over months to years, with the initial rapid deterioration gradually subsiding. Shaking the head or prolonged coughing fits can trigger a sudden onset of symptoms in a previously asymptomatic patient, possibly due to a low tonsil level. Syringomyelia is thought to be responsible for up to 5% of all paraplegias.

Syringomyelia can be caused by congenital craniocervical anomalies, including CM-1 and basilar impression. Other causes include tumors, trauma, arachnoiditis, meningitis, postoperative scarring and dysraphism. The incidence of CM-1 is between 3 and 8 per 100,000, with 65% of CM-1 patients being diagnosed with syringomyelia. The incidence of syringomyelia disease reported in the literature is 5.4 per 100,000 in Caucasians, compared to 1.94 per 100,000 in Japan.

Diagnostic differentiation from Chiari malformation

If the cerebrospinal fluid in the syringes cannot drain away and exerts pressure on the surrounding nerve tissue, this can manifest itself in a wide variety of symptoms (box). As syringomyelia is often associated with CM-1, investigation of the associated clinical features is crucial. In tussive headaches, coughing causes a sudden increase in intracranial CSF volume, resulting in transient suboccipital headaches and neck pain that occur fractions of a second after coughing. Headaches due to Chiari malformation are characterized as severe, pressure-like and only occasionally throbbing. They radiate behind the eyes and down to the neck and shoulders and are aggravated by physical exertion, Valsalva maneuvers, head heaviness and sudden changes in posture. Hoarseness and dysphagia, visual disturbances, oto-neurological disorders (dizziness, tinnitus, pressure in the ear, hearing loss, oscilloscopy), cerebellar disorders (tremors, dysmetria, ataxia, gait and balance disorders), syncope and sleep disorders are also common.

| Symptoms that can occur with syringomyelia |

| – adicular pain |

| – Paresthesia |

| – Reduced sensation of pain and temperature in the extremities |

| – Circulatory disorders |

| – Severe, migraine-like headaches |

| – Muscle weakness and impaired fine motor skills |

| – Spasticity in the lower limbs |

| – Horner syndrome |

| – Progressive scoliosis |

| – neuropathic pain |

The first symptoms before the intervention play a decisive role in predicting the outcome of treatment. Dissociative loss of sensation typically occurs in centrally localized syringomyelia. Some patients may also experience autonomic bladder dysfunction. Bowel dysfunction is rare.

The most common symptoms of syringomyelia include radicular pain, gait ataxia, sensory disturbances, dysesthesia, motor weakness, spasticity, autonomic dysreflexia and neuropathic pain. As syringomyelia progresses, spasticity tends to increase. The disease usually progresses slowly, with clinical symptoms often remaining stable for years.

MRI is the most reliable method for diagnosis

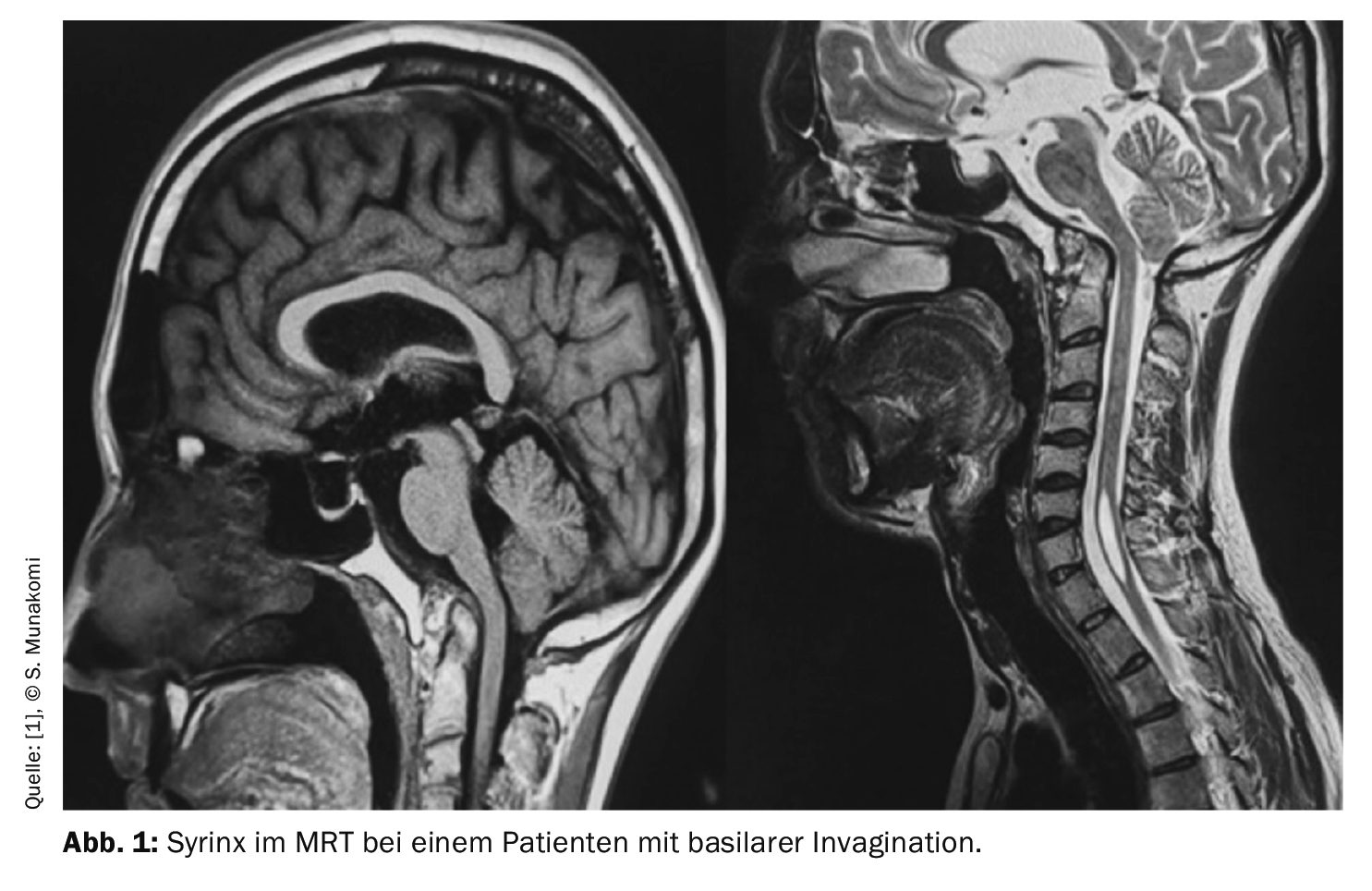

Magnetic resonance imaging with and without contrast medium is the preferred imaging method. The scan enables precise imaging of the relevant anatomy and accurate visualization of the syrinx in the sagittal and axial planes. MRI quickly provides crucial information such as the location, size and extent of the syrinx cavity as well as an assessment of the degree of cerebellar tonsil ectopy (Fig. 1).

Phase contrast MRA is used to examine the disturbance of CSF dynamics in detail. It also proves valuable in documenting postoperative changes in CSF flow and objective improvements. Myelography with high-resolution computed tomography (CT) is recommended in cases where magnetic resonance imaging is contraindicated. CT scans can effectively visualize dye that has entered the syrinx cavity. However, some authors have criticized CT myelography for its poor sensitivity in detecting CSF blockage. Although electromyography has no diagnostic value in syringomyelia, it helps to rule out peripheral neuropathy as a cause of paresthesias.

Treatment strategies for syringomyelia include avoidance of activities that increase venous pressure, such as exertion, neck flexion, and respiratory arrest, which may help relieve symptoms by reducing pressure, in addition to observation, symptom management, or surgery. Surgical interventions aim to correct the underlying pathophysiology of syringomyelia with the primary goal of improving CSF flow dynamics.

The prognosis depends on factors such as the underlying cause, the degree of neurological impairment, the location and size of the syrinx cavity and a syrinx diameter of more than 5 mm together with associated edema, which often heralds rapid deterioration. The rarity of the disease, its variable course and the limited follow-up periods further complicate the assessment of treatment. However, early surgical intervention is associated with fewer deficits and better outcomes.

Patients with untreated syringomyelia should avoid activities that may increase intracranial or intra-abdominal pressure, such as straining to defecate, coughing, sneezing and lifting heavy weights, to prevent worsening of symptoms and further enlargement of the syrinx. This caution is particularly important in the first few weeks after surgery, especially if patients are taking narcotic painkillers that can cause constipation.

Patients with Chiari malformation should avoid activities that strain the neck, such as roller coasters and trampolines, and avoid contact sports such as football, the authors write. Alternative forms of exercise such as swimming, stationary cycling and yoga are recommended.

Take-Home-Messages

- Syringomyelia should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any young person with progressive scoliosis. Early detection and treatment can reverse the deformity.

- Doctors need to differentiate Chiari headaches, and a patient’s medical history is crucial in this regard.

- Because it is a chronic condition, a patient with syringomyelia does not usually have symptoms such as anxiety, memory problems and depression. Doctors need to assess all symptoms appropriately, especially in view of the possibility that certain symptoms may improve after surgery.

Literature:

- Shenoy VS, Munakomi S, Sampath R.: Syringomyelia. StatPearls [Internet] 2024; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537110.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(12): 54–55