This time, a comprehensive overview of the current state of research in the field of targeted and immunological therapeutic approaches for metastatic melanoma was given at the Oncology Talks held at the Teufelhof Hotel in Basel, which is rich in tradition. Currently, intensively researched areas are mainly the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors and T cell reactivation.

Catharina Balmelli-Cattelan, MD, dept. Senior Physician Oncology University Hospital Basel, spoke about targeted therapies. BRAF mutations in melanoma were first described in 2002 [1]. Important subsequent studies with BRAF inhibitors were Brim-3, Break-3, and Break-MB.

Brim-3 [2]: Here, vemurafenib 2× 960 mg/d was compared in the first-line setting with dacarbazine in melanoma with stage IV BRAF V600E/K mutation. The extended follow-up of 2014 [3] showed a median overall survival of 13.6 vs. 9.7 months, a significant survival benefit of 30% with vemurafenib. Median progression-free survival was 6.9 vs. 1.6 months – the risk of progression was reduced by a significant 62%.

Break-3 [4]: This study also compared a BRAF inhibitor, dabrafenib, with dacarbazine as first-line treatment for stage IV melanoma (V600E/K mutation). An update at the 2013 ASCO Congress showed a 53% risk reduction in the primary endpoint, progression-free survival, with dabrafenib (6.9 vs. 2.7 months). Overall survival, the secondary endpoint, was 18.2 vs. 15.6 months with a hazard ratio of 0.76 (95% CI 0.48-1.21). After 15 months, 63% of patients in the dabrafenib group and 51% in the dacarbazine group were still alive. However, the crossover rate was very high at 59%. An update at three years showed survival rates in the above order of 31% vs. 28% with a HR of 0.81 (95% CI 0.56-1.18).

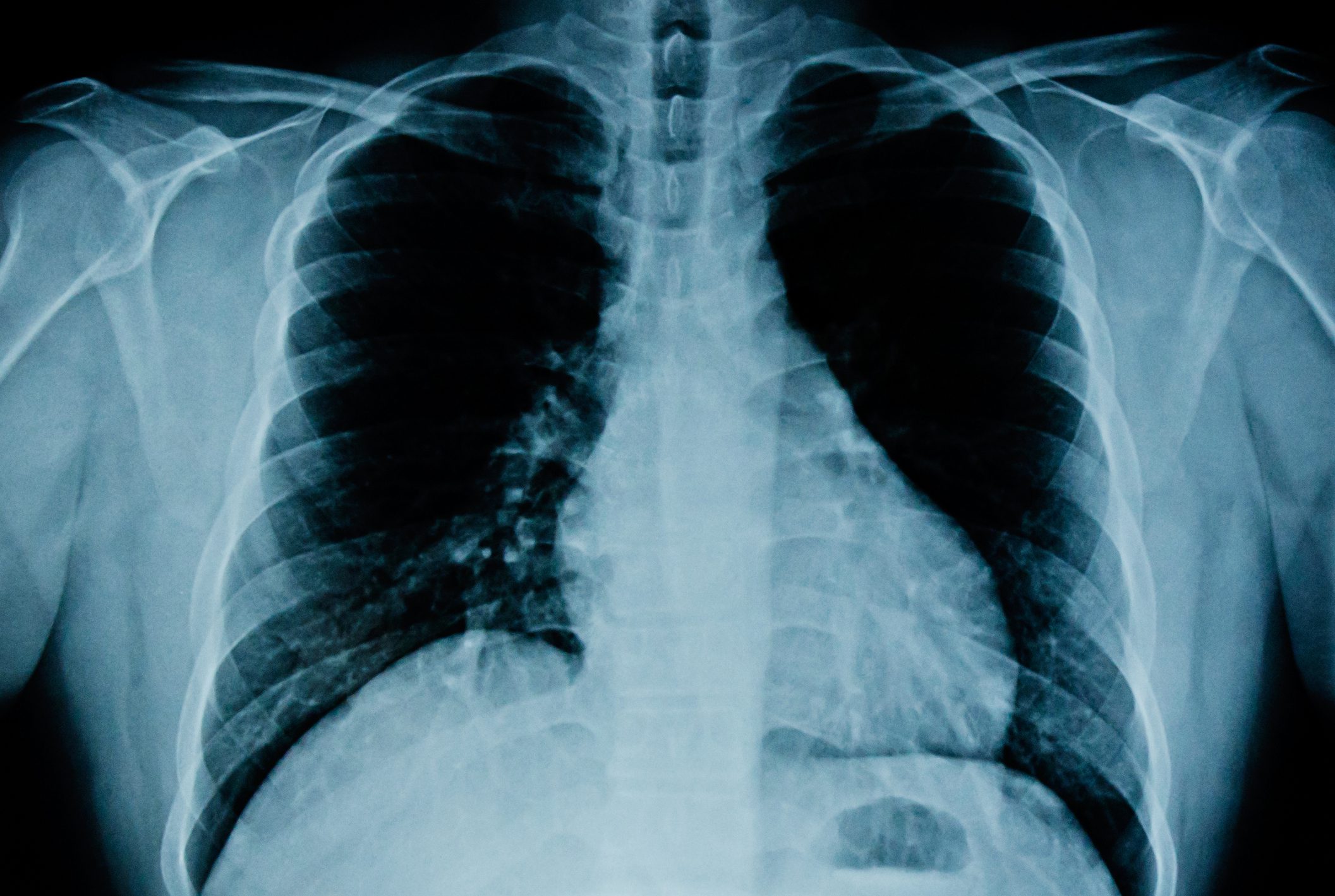

Break-MB [5]: Finally, Break-MB showed that dabrafenib also has good activity in patients with brain metastases.

“Specific inhibition of mutant BRAF yields high response rates and rapid response. Progression-free survival is about 7 vs. 2 months, and overall survival is 14-18 months,” Dr. Balmelli-Cattelan said. “Positive effects on quality of life and an effect on brain metastases have also been demonstrated. Some patients benefit from long-term therapy and tolerate it well.”

New approaches

Meanwhile, a good 13 years after BRAF was first described and after diverse research in this field, there are two new promising therapeutic approaches, namely the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors and T cell reactivation.

On the one hand, clinical factors such as ECOG performance status, metastasis (e.g., brain metastases), tumor burden and growth dynamics (imaging, LDH), and comorbidities (e.g., autoimmune diseases) influence the treatment decision in 2015. On the other hand, biological factors such as mutation status (BRAF, NRAS, cKIT), availability of therapy and patient selection play an important role. There are currently three interesting phase III studies on the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors:

Combi-d [6]: Here, dabrafenib and trametinib (arm 1) versus dabrafenib and placebo (arm 2) compared. The previously untreated patients had stage IIIc or IV unresectable melanoma with a BRAF V600E/K mutation. Median progression-free survival, the primary endpoint, was 9.3 (arm 1) vs. 8.8 months (arm 2). The risk reduction was thus a significant 25%.

Combi-v [7]: The same drug combination as above was compared here with vemurafenib and placebo. The study population was also comparable to that from Combi-d. The rate in overall survival, the primary endpoint, was 72% in arm 1 and 65% in arm 2 at 12 months (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.53-0.89; p=0.005).

CoBrim [8]: In this study, one group received vemurafenib and cobimetinib, and the other received vemurafenib and placebo. Patients with BRAF V600-mutated, locally advanced or metastatic melanoma without progression survived 9.9 months if they received the combination. In the other arm, survival was 6.2 months. Converted, these values result in a significant risk reduction with the combination of 49%.

In summary, higher response rates and rapid response are achieved with the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Progression-free survival was 10-11 vs. 7 months. There is also a clear benefit in overall survival. Note the altered side effect profile compared to monotherapies: more fever, more retinopathy, greater decrease in ejection fraction, and fewer cutaneous side effects. Overall, there are currently more data for parallel than for sequential therapy.

Immunological therapy

Three immune checkpoint inhibitors are available, according to Prof. Alfred Zippelius, MD, dept. Head of Oncology, University Hospital Basel, approved by the FDA: Ipilimumab (Yervoy®), Pembrolizumab (Keytruda®), Nivolumab (Opdivo®). The CTLA-4 and PD-1 checkpoints are used by cancer cells to override the cancer-specific immune response. By inhibiting them, the inhibitors activate the immune system or increase T-cell activity. Nivolumab binds to the PD-1 receptor on activated T cells. Thus, it prevents natural ligands such as PD-L1 and PD-L2 from interacting with the receptor. These ligands are overexpressed in certain tumors and are responsible for limiting T cell activation and proliferation. Nivolumab prevents the “braking” process and thus stimulates the immune system in its fight against cancer cells.

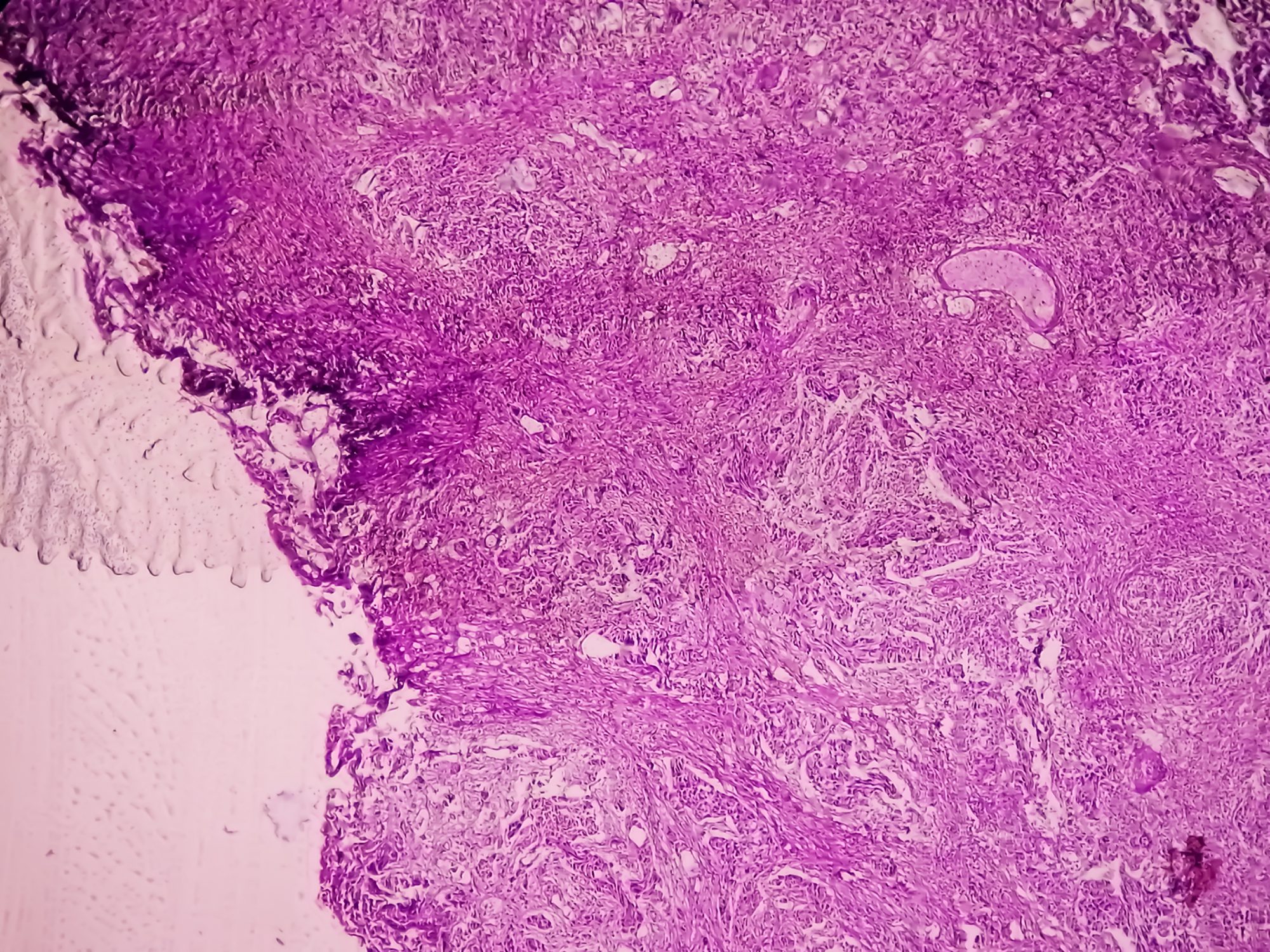

The anti-CTLA4 antibody ipilimumab even has a “curative” potential in certain patients: A very good and, above all, stable plateau is achieved under treatment, which is still present more than three years after therapy – this was shown by a pooled survival analysis of all phase I-III studies presented at the ESMO Congress 2013. Accordingly, the body “remembers” the gift for a long time and the positive effect is maintained. It is now central to search for predictive biomarkers that predict such a response and that can be used to select patients for immunotherapy. Research in this area is in full swing: initial results are available on the so-called neoepitopes. A specific tumor neoantigen signature appears to be associated with response to ipilimumab [9].

“Figuratively speaking, with immunotherapy you start the body’s own defense engine, release the brakes and step on the gas pedal. As a result, you have to be prepared for autoimmune reactions,” said the speaker. Ipilimumab is associated with various immune-mediated side effects, i.e. inflammatory processes due to increased or excessive immune activity: these may affect the digestive tract, liver, skin, nervous system, endocrine system or other organ systems.

Study situation on pembrolizumab and nivolumab

Following the promising phase I study Keynote-001 and the pivotal study Keynote-002, the results of the phase III study Keynote-006 were published in April 2015 [10], comparing pembrolizumab to ipilimumab for the treatment of unresectable advanced malignant melanoma (stage III or IV). Pembrolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands (PD-L1/-L2). So, in Keynote-006, two immunotherapies that target different immune checkpoint signaling pathways faced each other. The study was terminated early after the defined endpoints (progression-free and overall survival) were met early:

- Progression-free survival (PFS) showed median values of 5.5 months (pembrolizumab every two weeks), 4.1 months (every three weeks), and 2.8 months (ipilimumab). The risk of progression was thus significantly reduced by 42% with pembrolizumab compared with ipilimumab. After six months, the calculated PFS rates were 47.3% and 46.4% for pembrolizumab and 26.5% for ipilimumab.

- The 1-year overall survival rates were 74.1% and 68.4% in the pembrolizumab groups-compared with 58.2% with ipilimumab. This corresponds to a significant mortality risk reduction of 37% resp. 31%.

- Response rates were also improved with pembrolizumab: depending on the dose regimen, they were 33.7% resp. 32.9% vs. 11.9%.

- Grade 3 and 4 adverse events were more common with ipilimumab (19.9%) than with pembrolizumab (13.3% and 10.1%).

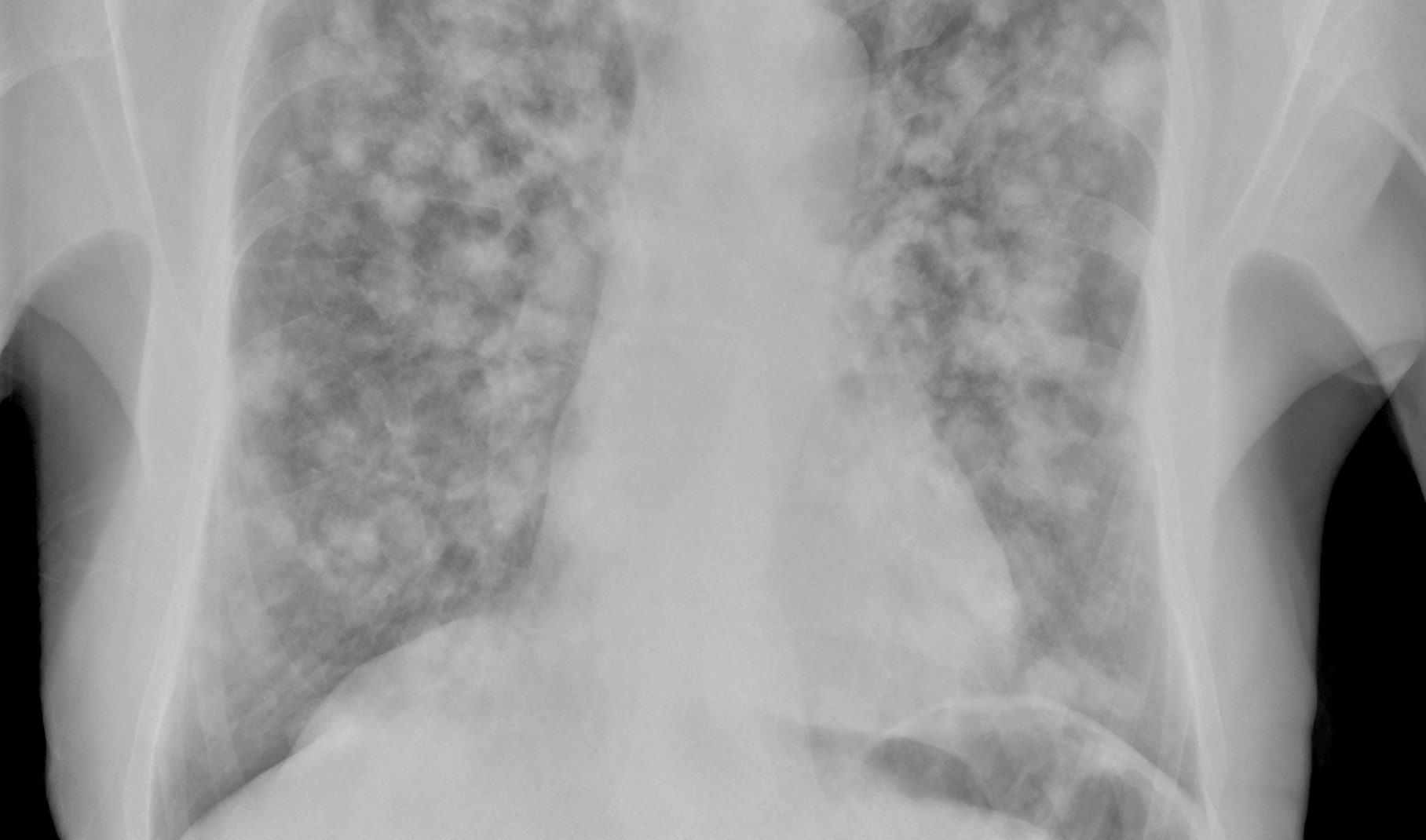

It has been established for some time that metastatic, ipilimumab-refractory melanoma responds better to the administration of nivolumab than to chemotherapy. With the phase III study CheckMate 066 [11] in early 2015, nivolumab was also shown to benefit previously untreated patients with advanced melanoma (BRAF wild-type): Compared with dacarbazine, 72.9 vs. 42.1% of patients were still alive after one year with nivolumab, representing a 58% reduction in the risk of death (HR 0.42, 99.79% CI 0.25-0.73; p<0,001). Median progression-free survival was 5.1 vs. 2.2 months (57 percent risk reduction). The objective response rate was 40% vs. 13.9% according to RECIST criteria 1.1.

“The days of first-line ipilimumab therapy are probably over once the new drugs are approved in this indication in our country,” Prof. Zippelius said.

Combined immunotherapies

There are also interesting results on the combination of different immunotherapies: The CheckMate-069 study (phase II) [12], published in May 2015 in the New England Journal of Medicine, compared the first-line combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab with ipilimumab monotherapy in 142 patients with advanced melanoma. The results are promising: 44 of 72 patients with BRAF wild-type responded to therapy in the combination group. This corresponds to an objective response rate of 61%. In the monotherapy group, this was only 11% (4 of 37 patients). The difference was statistically significant. The hazard ratio for progression or death was 0.4 (95% CI 0.23-0.68; p<0.001) – thus the combination reduced the risk of mortality/progression by 60%.

However, the higher sustained response rates and significant decrease in tumor burden were accompanied by an increase in adverse events: while 54% of patients experienced a grade 3-4 adverse event in the combination group, 24% did so with ipilimumab. There were three deaths associated with the combined treatment.

Source: 17th Basel Oncology Talks at the Teufelhof, May 21, 2015, Basel.

Literature:

- Davies H, et al: Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002 Jun 27; 417(6892): 949-954.

- Chapman PB, et al: Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 2011 Jun 30; 364(26): 2507-2516.

- McArthur GA, et al: Safety and efficacy of vemurafenib in BRAF(V600E) and BRAF(V600K) mutation-positive melanoma (BRIM-3): extended follow-up of a phase 3, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Oncol 2014 Mar; 15(3): 323-332.

- Hauschild A, et al: Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012 Jul 28; 380(9839): 358-365.

- Long GV, et al: Dabrafenib in patients with Val600Glu or Val600Lys BRAF-mutant melanoma metastatic to the brain (BREAK-MB): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012 Nov; 13(11): 1087-1095.

- Long GV, et al: Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition versus BRAF inhibition alone in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014 Nov 13; 371(20): 1877-1888.

- Robert C, et al: Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med 2015 Jan 1; 372(1): 30-39.

- Larkin J, et al: Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014 Nov 13; 371(20): 1867-1876.

- Snyder A, et al: Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014 Dec 4; 371(23): 2189-2199.

- Robert C, et al: Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. NEJM April 19, 2015. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093.

- Robert C, et al: Nivolumab in Previously Untreated Melanoma without BRAF Mutation. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 320-330.

- Postow MA, et al: Nivolumab and Ipilimumab versus Ipilimumab in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015 May 21; 372(21): 2006-2017.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(7): 27-29.