“Treatable traits” is the new magic term in the treatment of COPD, and the current guidelines are modeled after it. With regard to the structure of therapy, the focus should be on more individualized patient management that is not only based on symptoms, but also on markers such as blood eosinophils.

A typical case from everyday pneumology: A 64-year-old man has been suffering from exertional dyspnea for at least 3 years. He has occasional cough, no exacerbations, was a smoker for many years (42 pack years) but has currently quit. The only known secondary diagnosis is arterial hypertension, which is under therapy.

To better assess exertional dyspnea, Dr. Christian Clarenbach of the Department of Pneumology at the University Hospital of Zurich quantified the man’s dyspnea according to the mMRC scale. The patient was questioned and classified as grade I according to his answers (shortness of breath when walking fast on level ground or when climbing slightly). Lung function showed a typical concave flow-volume curve; after inhalation of a short-acting betamimetic, the curve improved only marginally without approaching the reference curve. The FEV1 value after bronchodilation was 56% of the target value. “The patient had at least moderate obstructive ventilation disorder, i.e., advanced lung disease that did not respond well to bronchodilation. Taking into account his history as a smoker, it was therefore possible to diagnose COPD,” said the expert [1].

The current treatment guidelines for such patients incorporate a variety of information: Until a few years ago, spirometry was basically the only determinant for the classification of GOLD stages in COPD. However, the rate of exacerbation and the extent of dyspnea are now also included. If a patient has no exacerbation or only one, he or she is classified into group A or B, according to the extent of exertional air distress (Fig. 1) [2].The patient in the case study had no exacerbations and also had an mMRC score of 1 and was therefore categorized in group A. For such patients, the guidelines recommend only a bronchodilator, regardless of other measures such as smoking cessation, self-management, more activity, pulmonary rehabilitation, etc. “It doesn’t even specify what kind of bronchodilator that should be,” Dr. Clarenbach noted.

Overtreatment with inhaled steroids in Switzerland

However, a look at the treatment reality in Switzerland shows that patients are treated to a large extent with inhaled steroids (ICS) already at level A [3]. This includes therapies consisting of LABA/LAMA/ICS as well as LABA/ICS and LAMA/LABA combinations. “So there is an overtreatment of inhaled steroids in COPD.”

Those who are helped by the bronchodilator may continue to take it

If you’ve given a patient a bronchodilator and they’re happy with it – and a lot of cases are – you can continue to treat them that way. With the bronchodilator, one causes an improvement in lung function, a reduction in symptoms, and often an improvement in performance. However, if shortness of breath continues to be a problem, the next recommended step is to first combine bronchodilators. “Then it’s also possible to switch within the different devices if a patient doesn’t like one treatment so much, for example, because of the inhalation technique.” Even in patients with frequent exacerbations, two bronchodilators should be combined, but what is new is that only when the patient also has a blood eosinophilia is it recommended to treat additionally with an inhaled steroid. Accordingly, patients with recurrent exacerbations and those with elevated blood eosinophilia ultimately benefit most when an inhaled steroid is added. In addition, for a subgroup with chronic bronchitis and FEV1 <50%, roflumilast is an option, and in former smokers, azithromycin may be considered as options to reduce the rate of exacerbations.

Is it allowed to withdraw ICS?

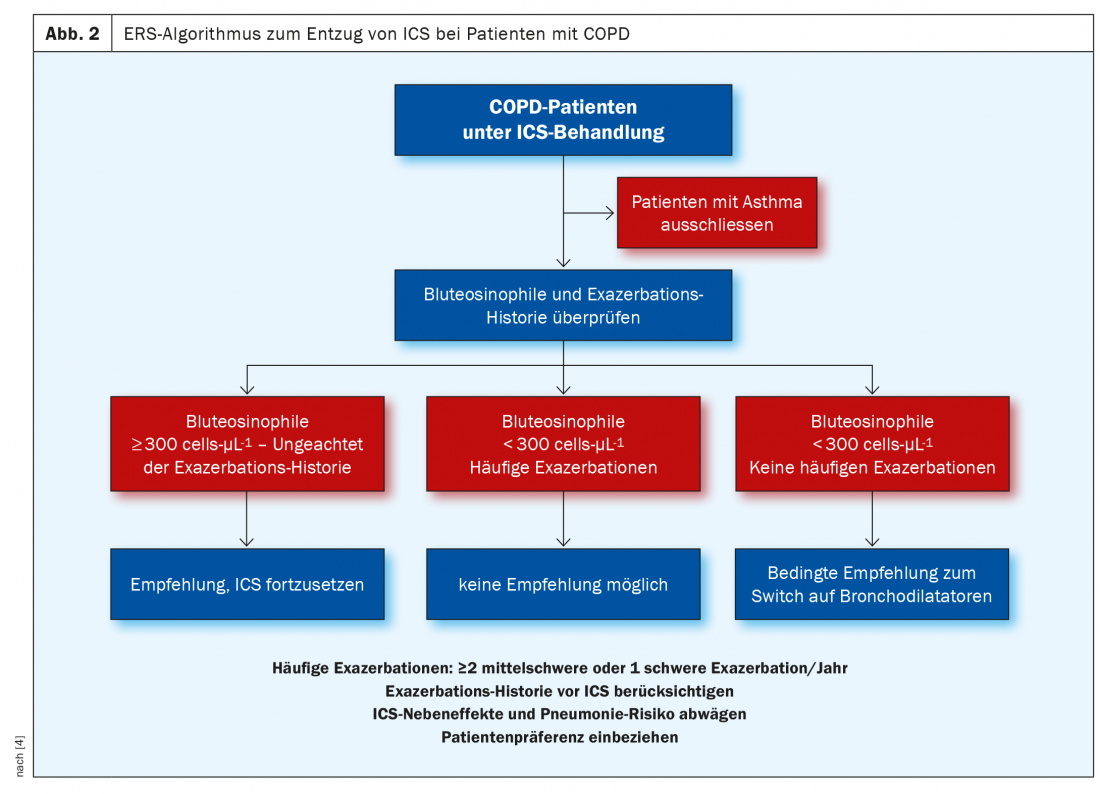

However, what happens to COPD patients already on ICS who are withdrawn from the steroid – does this affect FEV1, exacerbations and/or symptoms? There are now four randomized-controlled trials on this question, which were considered in a systematic review. This has resulted in a treatment recommendation on how to proceed with the patient in such a situation:

Only for COPD patients who have high blood eosinophilia (≥ 300 cells/μl, there is a clear recommendation for continued treatment with ICS (Fig. 2) . For those patients who are not eosinophilic and also do not have exacerbations, it is safe to discontinue and withdraw ICS. No clear recommendation could be made with regard to patients who have many exacerbations but are not eosinophils – the results differed depending on the study.

For clarity, Dr. Clarenbach also cited the number needed to treat (NNT) that would be required to avoid an exacerbation when treating with inhaled steroids: If you give ICS to patients with ≥ 300 Eos/μl, you only need to treat 9 people to avoid an exacerbation. In patients who are non-eosinophilic (<300 Eos/μl), on the other hand, the NNT is already 46. “So you have to think carefully about whether you want to continue giving patients inhaled steroid therapy, especially if they are non-eosinophilic,” was the conclusion of the Zurich pulmonologist.

Source: FomF WebUp Pneumology

Literature:

- FomF WebUp Pneumology, Dec. 7, 2020; www.fomf.ch/webup/pneumologie-6-highlights-60-min-07-12-20.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, 2021 Report; https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GOLD-REPORT-2021-v1.1-25Nov20_WMV.pdf.

- Grewe FA, Sievi NA, Bradicich M, et al: Compliance of Pharmacotherapy with GOLD Guidelines: A Longitudinal Study in Patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2020; 15: 627-635; doi: 10.2147/COPD.S240444.

- Chalmers JD, Laska IF, Franssen FME, et al: Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: a European Respiratory Society guideline. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 2000351; doi: 10.1183/13993003.00351-2020.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2021; 3(1): 18-20.