The majority of simple surgical procedures on the skin organ can be easily performed in the office. However, as with any surgical procedure, a clear indication and selection of the appropriate surgical procedures, in addition to a flawless surgical technique, are crucial. In the following article, in addition to a brief summary of the most important indications for minor hair surgery procedures, some tips and tricks for their good success will be given.

A large part of skin surgery involves the removal of skin tumors. In skin tumor surgery, as always, the focus is on complete, histologically confirmed tumor removal. In addition, the preservation of function, e.g. lip or eyelid closure, is central. Thirdly (but often very important for the patient), the aesthetic result of the surgical procedure should be as harmonious as possible.

Among malignant and semi-malignant tumors, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is by far the most common, followed by spinocellular carcinoma (SCC), which is about ten times less common. The typical clinical picture – in BCC a glazed papule with telangiectasia and sometimes central ulceration, in SCC often a somewhat hyperkeratotic tumor – is not always present. It is not uncommon for patients to simply present with a non-healing small wound in a sun-exposed area, which is often mistakenly associated with a previous injury due to the need for causality. If the entire tumor can be easily removed with a spindle-shaped excision and the defect directly resealed when BCC or SCC is clinically suspected, such an excisional biopsy can be performed. In all other cases, a punch biopsy or, at times, a shave biopsy is best suited for diagnosis in this case.

Punch and Shave Biopsy Technique

Punch biopsy is excellent for diagnosing virtually all skin tumors as well as many inflammatory diseases. A representative area, preferably in the center of nodular portions of the tumor, is infiltrated with local anesthesia. The biopsy punch is then inserted up to the stop. The skin should be pre-tensioned slightly transversely to the course of the skin cleavage lines, resulting in an oval defect afterwards. This can then be easily closed with one or two stitches with single button seams with a skin thread.

In inflammatory skin diseases, the punch biopsy should rather be taken from the edge of a lesion that is as fresh as possible. To obtain a sufficiently large biopsy for reliable histological diagnosis, a 5 or 6 mm punch should be chosen in these cases; for the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, a 3 or 4 mm punch is also sufficient.

For the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, a shave biopsy is also sufficient in some cases, in which a piece of the tumor can be taken tangentially with a ring curette or a flexible blade after placing a wheal with the local anesthetic. In these cases, hemostasis is performed with, for example, a ferric chloride solution or the electrocautery.

Simple excision

The technique of excision depends on the histologic subtype of a BCC or SCC. Nodular basal cell carcinomas can be excised with a lateral safety margin of 3-4 mm, which is often well feasible in practice. It is important that all excisions are histologically processed and that the histological report controls whether the excision was made in sano. Incomplete excision results in tumor recurrence in more than 20%, so an observational approach is indicated only in rare cases.

The excision defect can then be closed in the direction of the skin cleavage lines. In most cases, it is recommended to excise the tumor along its clinical border and adjust the defect afterwards during closure by correcting “dog ears” to allow linear closure. For spinocellular carcinomas, excision with a 5-7 mm safety margin is recommended; for moderately and poorly differentiated spinocellular carcinomas and infiltrative (cirrhotic) basal cell carcinomas, a 7-10 mm safety margin is indicated. If this excision results in a large excisional defect, as well as in tumors with an infiltrative growth pattern or in anatomically difficult locations (nose, ears, etc.), excision with Mohs surgery is often indicated (see next section). In these cases, the more beautiful and functionally better result is often achieved by closing the defect with flap surgery.

Incision margin controlled surgery (Mohs surgery)

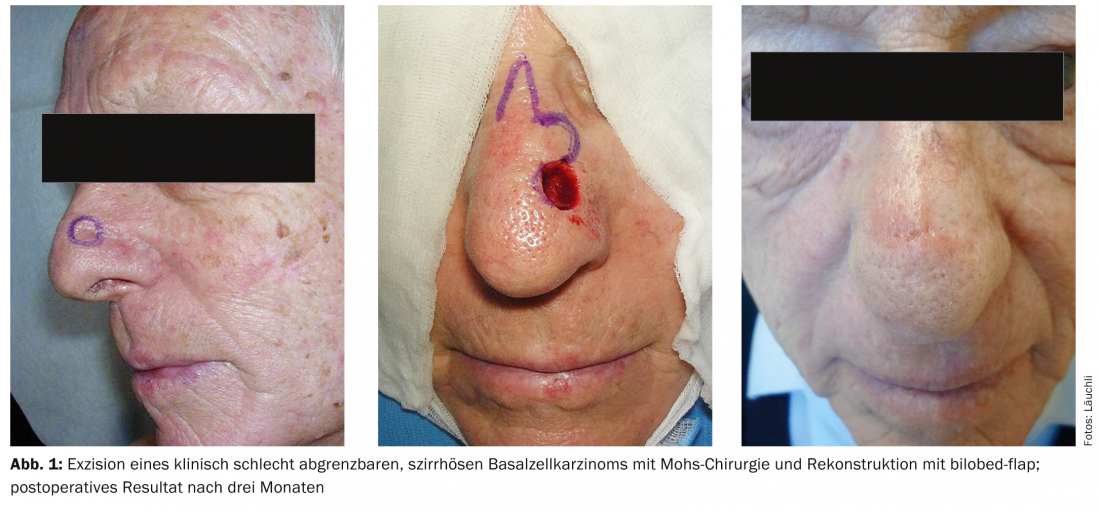

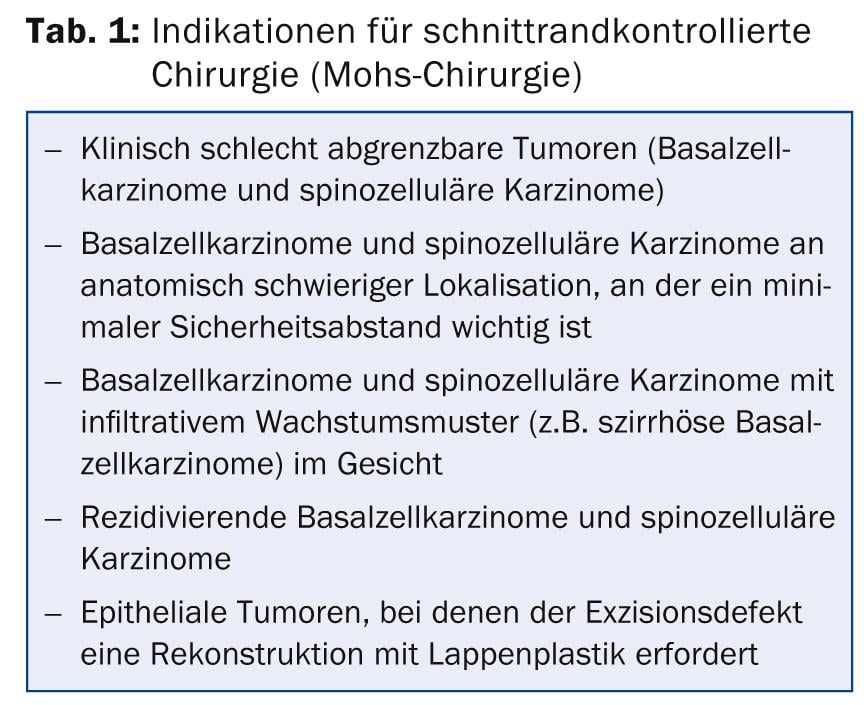

Mohs surgery was developed by American dermatosurgeon Frederic Mohs in 1941 and described in the form practiced today by Tromovic in 1972. The principle is that a tumor is excised in a bowl shape with the smallest possible safety distance. The excisate is then embedded using a special histological technique so that the entire lateral and also the basal edge of the incision can be prepared in a preparation using the frozen section method and evaluated by the dermatosurgeon himself. Targeted re-excisions can then be made where margin-forming tumor components are identified. This technique provides the greatest possible certainty of complete excision, and the recurrence rate can be reduced, for example, for nodular basal cell carcinoma from 5% after conventional excision to 1-2% after excision with Mohs surgery. The advantages are even greater in recurrent tumors and in infiltrative tumors, where the recurrence rate can be reduced from about 18 to 5%. For the patient, the main advantage of the method (besides the greater oncological safety) is that excision and securing of tumor-free incision margins can be performed on the same day and that primarily a smaller safety margin can be chosen, resulting in smaller excision defects or scars. Excision of an epithelial tumor with Mohs surgery is thus indicated when the smallest possible safety margin should be chosen, e.g., when the tumor is located in an anatomically difficult site or when flap plasty is necessary for reconstruction. In addition, the technique is indicated for excision of clinically poorly demarcated and all infiltrative epithelial tumors (e.g., cirrhotic basal cell carcinoma, Fig. 1) in the facial region (Table 1).

Mohs surgery is one of the standard procedures for excision of most epithelial skin tumors in the USA, and in Switzerland it is offered at all dermatological university hospitals and in some dermatological practices.

Nevi and melanoma

In nevus cell nevi, an important aspect of treatment is to avoid unnecessary excisions. If malignant melanoma is clinically suspected, the lesion should be excised in toto with a close safety margin if possible. Although an increased rate of metastasis from trial excisions has not been demonstrated, smaller biopsies for melanocytic lesions should be performed only in exceptional cases, such as when a lesion is too large for total excision. Complete excisional biopsy greatly facilitates histologic evaluation and correct tumor staging, which is also critical for further management. Thus, in general, it is worthwhile to perform a careful preoperative diagnosis, which should include dermoscopy by a skilled dermatologist in addition to clinical evaluation.

If nevi are removed for cosmetic reasons, or because they bother the patient, they can be addressed in most cases with a simple spindle-shaped excision. However, since this usually results in quite visible scars, restraint is indicated in such cases. The shave excision of nevi should be reserved for experienced dermatosurgeons only, as it can result in unsightly, large scars if performed poorly, and it can make histologic evaluation difficult if performed too superficially. Excised nevi should be evaluated histologically in all cases, as melanoma can never be excluded with certainty in a pigmented lesion even in the absence of clinical suspicion. Removal of nevi with ablative procedures or by laser should be avoided in any case. Apart from the lack of histological evaluability, there are often cosmetically unfavorable results and frequent recurrences, which histologically appear under the image of pseudomelanoma, which cannot be reliably distinguished from malignant melanoma.

If histologic workup reveals malignant melanoma, a re-excision with a wide safety margin is indicated depending on the depth of tumor invasion, as well as sentinel lymph node biopsy if necessary. These procedures are usually performed by a plastic surgeon or dermatosurgeon, who can also provide further tumor follow-up care.

Cysts

Epidermoid and trichilemmal cysts can usually be excised well if they do not have inflammatory changes. For this purpose, after local anesthesia has been given, a careful incision can be made over the cyst dome in the direction of the skin cleavage lines without injuring the cyst. This can then be dissected out with a pair of pointed scissors (Stevens scissors). The defect can normally be adapted without any problems due to the lack of tension, although the subcutaneous suture is particularly important here to avoid a larger cavity. Alternatively, cysts can also be opened in the region of the porus with a punch and then the cyst sac removed by pulling it out with forceps and curettage if necessary. This technique is easier, but the untrained person is often left with cystic sac remnants, which can lead to recurrences. Inflammatory cysts can either be excised à froid after the inflammation has subsided or incised widely around the inflammatory lesion in the inflammatory state after local anesthesia has been placed, and the entire cyst contents and cyst sac can be curetted with a sharp spoon. This defect should be tamponaded with a mèche, which should be changed daily until the inflammatory changes subside.

Surgical Technology

Local anesthesia: Almost all skin organ procedures can be performed under local anesthesia. This is painless for the patient if some aspects are taken into account. The use of a buffered local anesthetic with the addition of sodium bicarbonate in a ratio of 1:4 can reduce the burning sensation during injection. In addition, pain during injection is significantly reduced by using a thin needle and slow injection, as painfulness often results primarily from rapid tissue expansion. Further, distracting the patient, whether by talking or pinching the environment, vibration, or cold stimuli is helpful.

Local anesthesia can be performed in almost all cases with the addition of epinephrine. This not only reduces diffuse bleeding during surgery, but also increases the duration of action of the local anesthetic. The surgical principles that local anesthesia with the addition of epinephrine to the acra is contraindicated are outdated, practically no confirmed cases are described in the entire surgical literature. However, caution is advised for conduction anesthesia of fingers and toes and in patients with vascular compromise.

Incision direction: Spindle-shaped excisions or incisions should always be made in the direction of the skin split lines. These can be found as schematics in various surgical textbooks. However, in most cases it is easier to pinch the skin in different directions to determine in which direction there is the least resistance (Fig. 2).

In the face, the natural wrinkles through the facial expression can also be used to help determine the excision line. In the face, it is particularly important that wound closure does not cause traction on a free edge (eyelid, nostril, lips), which would distort them.

Suture technique: For defect closure after excisions on the skin organ, a skin suture with monofilament suture material is recommended in most cases. Since scar lines always retract during the healing process, care must be taken to ensure good eversion of the wound edges by the suture. This can be achieved, for example, by a subcutaneous suture before skin closure or by a special suture technique such as the Donati suture or the horizontal mattress suture (Fig.3). Particularly in the face, care must be taken to select the finest possible thread and to place the puncture sites close to the edge of the incision in order to produce an optimal cosmetic result without puncture canals visible later. Also helpful is the correct retention time of the suture material, which should not exceed five to seven days in the face. However, sutures can be left on the body for ten to 14 days without further ado, until sufficient strength of the scar has been achieved.

Instead of a pure subcutaneous suture, a subcutaneous-cutaneous suture is placed in most cases to give the scar more strength in the longer term and to efficiently reduce tension during wound closure. However, these sutures should also not be placed too superficially, as otherwise part of the suture material often works its way out through the surface of the skin (“spitting sutures”). Here, the aspect of resorption time has to be considered when selecting the suture material. While well-braided suture material with a shorter resorption time can be used on the face, an absorbable suture with a long half-life is particularly advantageous on the back, as otherwise the lack of scar stability after suture removal usually results in wide, unsightly scars.

Complications

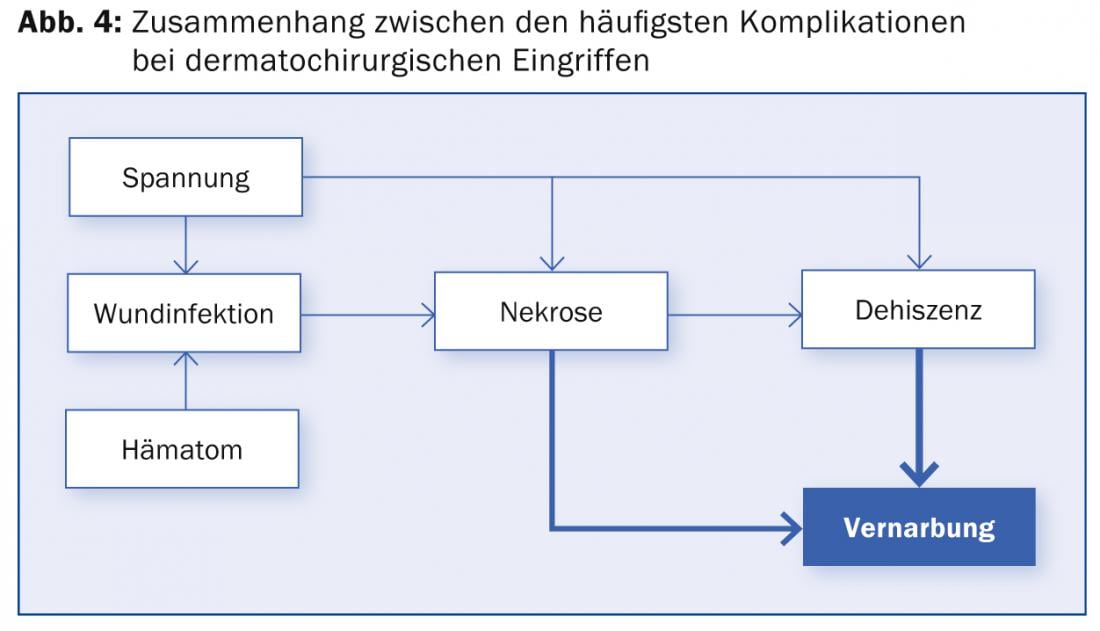

The most common complications after hair surgery are post-operative bleeding and wound infections (Fig. 4) . Both are favored by excessive tension in the wound, by a too large excision defect, an inappropriate choice of wound closure or lack of lateral mobilization. However, wound infections occur in less than 1% of hair surgery procedures when performed in a sterile fashion. General preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicated for skin procedures. Only in immunosuppressed patients or in procedures in or near infected areas or near orifices (nose, ears, genital region) and occasionally on the lower extremities can it be recommended.

Anticoagulation: To avoid postoperative bleeding, precise hemostasis must be performed, especially for larger excisions. The bipolar electrocautery is best suited for this purpose, as it can also be used in patients with pacemakers. Oral anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy should not be discontinued preoperatively. There has been a clear consensus in the recent literature that the complications from any rebleeding are in almost all cases more manageable and less devastating to the patient than potential complications from discontinuation of anticoagulation. For oral anticoagulation, a current INR value should be available, preferably not above 2.5.

Patient education: As with all surgical procedures, detailed preoperative information must be provided to the patient about the indication and necessity of the procedure, possible consequences of not performing it, and complications. This must also be documented in writing. In particular, the patient should be made aware of the formation of a long visible scar, as this is underestimated by many patients.

The correct assessment of one’s own abilities and the timely involvement of a colleague experienced in dermatosurgery is an important success factor in all procedures on the skin organ.

Dr. med. Severin Läuchli

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- A large proportion of skin surgery procedures involve the removal of skin tumors (basal cell carcinoma and spinocellular carcinoma).

- Punch biopsy is suitable for the diagnosis of most skin tumors as well as many inflammatory diseases. For the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, a shave biopsy is sometimes sufficient.

- The technique of excision depends on the histologic subtype of a BCC or SCC.

- Mohs surgery offers the greatest possible safety of a complete excision with the smallest possible scar.

- An important aspect of treatment in nevus cell nevi is the avoidance of unnecessary excisions.

- Most skin organ procedures can be performed under local anesthesia.

- The most common complications are post-operative bleeding and wound infections, which can usually be prevented with adequate technique.

A RETENIR

- Une proportion importante des interventions chirurgicales cutanées concerne l’exérèse de tumeurs cutanées (carcinome basocellulaire et carcinome spinocellulaire).

- La biopsie au punch convient pour le diagnostic de pratiquement toutes les tumeurs cutanées ainsi que pour de nombreuses maladies inflammatoires. Un shaving de la lésion est également souvent adapté au diagnostic d’un carcinome basocellulaire.

- La technique de l’exérèse est déterminée par le sous-type histologique d’un CBC ou d’un CSC.

- La chirurgie de Mohs offre la meilleure sécurité possible d’une exérèse complète avec une cicatrice la plus réduite possible.

- Un aspect important du traitement des nævus nævocellulaires est d’éviter les exérèses inutiles.

- La plupart des interventions sur la peau sont réalisables sous anesthésie locale.

- Les complications les plus fréquentes sont des saignements post-opératoires et des infections de la plaie qui peuvent cependant être le plus souvent évitées par une technique adéquate.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2014; 24(3): 21-25