Prior to reconstruction, the detected skin lesions should always be examined histologically. There are a number of things to consider during a surgical procedure, including adequate instrumentation and consideration of multimorbidity. In more complex cases, referral to specialists and/or involvement of an interdisciplinary tumor board is recommended.

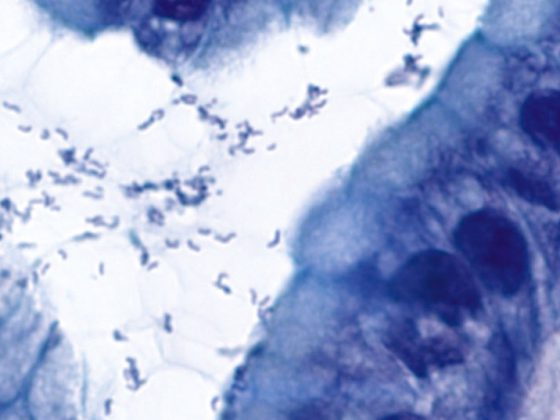

As the population ages, malignant skin lesions such as actinic keratoses, Bowen’s disease, basal cell carcinomas, spinaliomas, and melanomas are becoming more common in the daily lives of primary care providers. In the senium, the majority of patients have suspicious skin changes, especially in the area of the sun-exposed skin in the head and neck region (Fig. 1) . It is often difficult to distinguish whether the lesion is still an actinic keratosis (carcinoma in situ) or already an infiltrating skin carcinoma. In case of doubt, it is recommended to obtain certainty by intracutaneous shave excision with a 10-blade or, for larger defects, with one or more 2-mm punch biopsies. Whether a local anesthetic (LA) with Emla®, an injection with a local anesthetic or, if necessary, an LA can be omitted for a 2-mm trial excision must be decided on a case-by-case basis. Noticeably growing skin lesions that bleed, ulcerate, or are suspicious to the examining physician should always be biopsied to plan further action. For possible surgical rehabilitation, it is helpful if the shave excisate is marked with a thread. The location of the suture mark should be mentioned on the histology form to help guide the histopathologist and later the surgeon. In the case of unmarked skin spindle with incompletely excised skin carcinoma, the defect will inevitably become larger during post-excision.

Planning the process

Depending on the result of the histological examination, it must be assessed, if necessary in consultation with a dermatologist, whether immunomodulatory therapy with, for example, imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, photodynamic therapy (PDT) or, if necessary, a physical measure such as curettage, cryotherapy, laser ablation, irradiation or surgery should be recommended. Infiltrating skin carcinomas must be removed in such a way that histologic examination can confirm complete excision. Radiotherapy (RT) has a place mainly in “inoperable patients” and at most in surgically complex sites (nasal wing or eyelid margin, medial corner of the eye, lip). The disadvantage of RT is that it is not possible to estimate whether the tumor is really completely removed against the depth. It also carries a risk of radioosteo- or chondronecrosis.

The treatment of skin carcinomas depends on many circumstances and can thus vary even if the initial situation is similar. In patients with double platelet aggregation inhibition, dementia or very elderly patients who live alone, the procedure must be weighted differently than in healthy, spry patients with high esthetic demands. Also tumor-independent factors, such as the ability to transport the patient, the postoperative care required, or the need to wear glasses or hearing aids, help to determine whether, at best, radiotherapy, a multi-stage surgical procedure, or a single procedure with frozen sectioning and defect coverage with a full-thickness skin graft are more appropriate. For this decision to be made, communication between the family doctor, patient, relatives, nursing institution and, if necessary, radiooncologist, dermatologist, ENT or plastic surgeon must be well coordinated in advance of the planned treatment. Case presentation in an interdisciplinary tumor board makes sense especially for extensive, already metastasized tumors, for melanomas and for patients with pronounced polymorbidity. Estimating the safety distance of an excision must be discussed on a case-by-case basis because, for example, a safety distance on the face of 2 cm has serious consequences for defect coverage. Parameters that define the extent of excision are histology, tumor diameter, depth of infiltration, and the topography of the findings.

Dementia patients

For persons with dementia, analgesia may need to be planned for surgical treatment, requiring increased human resources and appropriate infrastructure with postoperative monitoring. There is a risk of cover dressings being torn away and wounds being torn open postoperatively, which must be taken into account when planning treatment. If necessary, radiotherapy is the more practical form of therapy in this situation. Pedicled flaps, which require multiple procedures, tend to be avoided. Preference is given to tumor excision and simple defect coverage, preferably performed in a single session.

Cut edge control

Performing defect coverage without knowing if the tumor is completely removed carries a risk of recurrence. In well-demarcated solid basal cell carcinoma, this risk can be estimated by eye sooner than in a cirrhotic tumor. In case of doubt, an incision margin check must be planned before the defect is closed. In dermatological institutes, surgery is often performed using the “Mohs technique”. During this procedure, the dermatosurgeon examines the excised tissue himself and, if necessary, makes a re-excision and finally covers the defect. If this option is not available and a one-stage procedure is unavoidable (example carcinoma of the lips or lid margin), then a frozen section examination is recommended. Such a timely histological examination, which as a rule can rarely be performed in-house outside of center hospitals, places high planning demands on the efficient use of the operating room. A much more practical approach is a multi-period approach. In this case, the defect is not covered until 2-3 days after excision and subsequent examination of the incision margins by a dermatohistopathologist in an external laboratory. This staggered approach takes the time pressure off the histopathologist and gives the surgeon a chance to discuss the various reconstruction options with the patient at their leisure.

Platelet aggregation inhibition

In addition to informing the patient (and usually his or her relatives) about the planned excision and the options for covering the defect, the question now often arises as to whether medications that have an effect on blood clotting can be paused before the procedure. With impaired blood clotting, it is not so much the procedure itself as the time afterwards that is uncomfortable for the patient. In the midface, placement of a compression bandage is difficult. Bleeding after reactive vasodilatation, an hour after the procedure, can often become uncomfortable. In the case of double platelet aggregation inhibition, the question arises whether surgery can be delayed or whether radiotherapy would be a better treatment option. In general, however, the intraoperative and postoperative problems associated with surgery during antiplatelet prophylaxis or anticoagulation are usually less dangerous than the potentially lethal risks after discontinuation of the medication.

Local anesthesia

Infiltration anesthesia is particularly painful in the face. It is recommended to use very thin 30-gauge cannulas and, if possible, to inject a depot of the local anesthetic at the nerve exit sites. The effect of the nerve block is not immediate, so it makes sense to place the LA at least 5-10 minutes before the skin incision. A long 30-gauge syringe needle can be used to inject lidocaine 2% (100 mg/5 ml) from the vestibule of the nose and oral cavity toward the foramens infraorbitale and perinasally toward the dorsum of the nose or medial corner of the eye for tumors in the midface. The painfulness of the injection can be somewhat reduced by a cotton swab soaked with a lidocaine 10% spray and inserted into the nasal vestibule or the oral vestibule 5 minutes before the injection. The addition of sodium bicarbonate Sintetica® 8.4% (ratio 1:9) buffers the solution and reduces the unpleasant sensation of burning during infiltration, especially in the case of perifocal inflammatory reaction. However, if the solutions are not mixed together immediately before infiltration or if they are taken from the refrigerator, the effect of local anesthesia will be less. The addition of a vasoconstrictor (usually epinephrine 5mcg/ml) is also very helpful in the ear and nose to prolong the duration of LA action and reduce bleeding. At most, the addition of a vasoconstrictor to the LA is omitted in patients who have smoked intensively for years on the auricles, which tend to have poor blood supply. A general refrain from adding adrenaline to the ears and nose, as described in older textbooks, unnecessarily complicates the operation. More serious is the impairment of blood flow due to vascular factors. In long-time smokers with cold, gray skin, poor local circulation must be considered when planning reconstruction. A full-thickness skin graft to the auricle or nasal tip on exposed cartilage is at high risk of necrosis in this situation, so a local displacement flap is often the safer solution.

Surgical resection

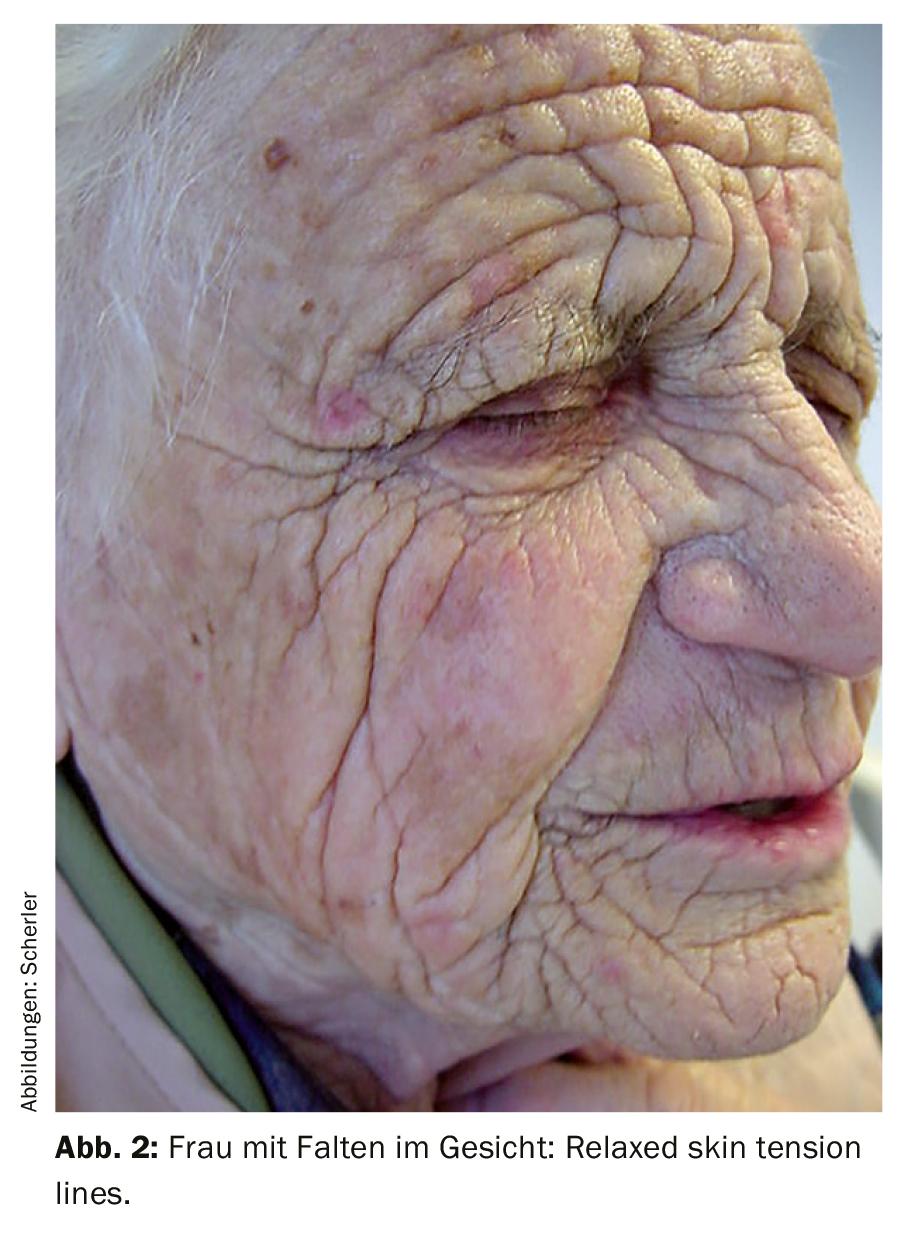

The “learning curve” in surgical reconstruction of facial defects is not linearly steep. Scar contraction or color changes are only visible after many months. More stringent requirements apply if ugly distortion of the lips, nasal margin or postoperative ectropion of the lower eyelid is to be avoided. Which of the various flaps is used to cover defects in the neck, cheeks or forehead is not so important as long as the technique is mastered and, above all, as long as the RSTL (“relaxed skin tension lines”) are taken into account. (Fig. 2). A scar that is transverse to the RSTL is sometimes difficult to correct, even with multiple Z-plasties, and should be avoided whenever possible, even during the first procedure. The patient will never blame the attending physician for referring him to a more experienced colleague.

Instrumentation, suture material, and hemostasis options should be oriented for facial procedures. Fine Adson-Brown forceps, Gillies incisal hooks, fine non-adhesive bipolar electrocautery forceps and, at most, the radiofrequency device can be used to treat the thin, delicate facial skin much more atraumatically than standard wound care disposable instruments or the laser. Avoid squeezing the skin edges with surgical forceps that are too large. Wound edges should preferably be grasped subcutaneously or with a single-pronged hook, adapted orthogradely, and sutured invertingly. The suture material for the skin should be monofilament, non-absorbable 5-0 or 6-0 skin sutures. These can be removed from the face after only 5-7 days, and from the neck, scalp area and forehead after 7-10 days. For subcutaneous sutures in the cheek soft tissues, neck and for excisions of the lip, absorbable Dexon® or Vicryl® sutures of strength 4-0 are chosen. In the scalp soft tissues, a 3-0 or even 2-0 suture thickness may sometimes be necessary subcutaneously, depending on the traction required. In the hairy scalp, occasional skin staples are an easy and quick option for skin closure. Periocular, auricular and nasal subcutaneous sutures are usually not necessary. In these regions, the use of magnifying glasses and microinstruments are useful. For cartilage sutures on the auricle and nostril, absorbable suture material of 4-0 or 5-0 strength is used, and it should be noted that the cartilage ends are adapted in figure-8 suturing technique to avoid overlapping of the cartilages.

In the case of a displacement flap plasty, it must be estimated in advance in which direction the traction vector will lie. It must never be directed against the lower eyelid, against the edge of the nostril or the red of the lip, because then in the medium term an ectropion or distortion of the lip or the edge of the nostril can hardly be avoided.

Hemostasis is of great importance not only in patients with antiplatelet therapy. The procedure is usually performed in vasoconstriction. Reactive vasodilation one hour later can lead to an uncomfortable hematoma if hemostasis is insufficient, which is why a small flap is inserted at the caudal wound edge as a precaution in case of doubt. A strip from a sterile glove is suitable for this purpose. Suction drains are occasionally used for larger displacement flaps on the neck or scalp.

Defect coverage

Once the tumor is removed, the excisate is marked with a thread. If a multi-period procedure is planned, the defect must now be temporarily covered. A simple and inexpensive option for this is ointment strip mèches (Fig. 3), which are coated with a polyvalent ointment. For this purpose, an 8 mm wide dry “ear mèche” of the desired length can be inserted, for example, into a tube of Topsym PV®, Terracortril® or Triderm® and pulled out again covered with ointment. Even after several days, the wound covered with the ointment strip subsequently looks completely irritation-free.

If primary closure of the defect is planned, either subcutaneously with generous mobilization or with a displacement flap, the varying skin thickness, for example periocularly and on the bridge of the nose, must be taken into account. Adaptation of the skin edges should be done in the same plane. Intracutaneous sutures are nice, especially for long incisions on the neck, but should only be placed when there is increased traction in the cheek area if the tension has been relieved with subcutaneous sutures and the skin edges can be adapted without tension. Anchorage to the periosteum or in a drilled hole at the orbital rim or at the apertura piriformis is often safer in the midface than deep sutures placed subcutaneously only.

Full-thickness skin graft

In the area of the cheek or neck, an excision site can be covered with a displacement flap in the vast majority of cases. Above a certain defect size, this is hardly possible on the forehead, which is why a full-thickness skin graft can be useful. While smaller full-thickness skin grafts can be taken for defects of the nose or periocularly from the nasolabial folds, periauricularly, or even from the forehead, larger-area grafts are more likely to be taken from the lateral neck or from the supraclavicular fossa. Full-thickness skin grafts are simple reconstructions; however, not only are their color and texture different, they are usually thinner than the surrounding skin and they have a tendency to shrink (Fig. 4). Therefore, in younger patients with higher cosmetic demands, full-thickness skin grafts tend not to be the first choice. After healing, the affected areas on the face could be covered with some makeup.

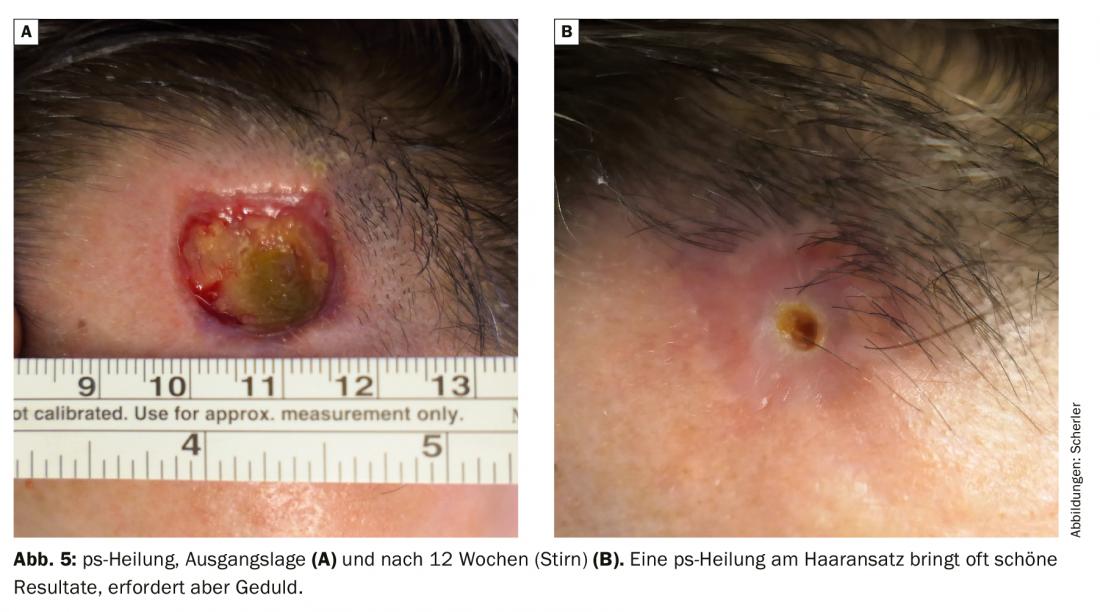

Healing per secundam intentionem

The importance of wound healing “per secundam intentionem” (ps-healing) is often underestimated. Especially on concave areas of the nose flank, but also in the scalp area and on the forehead defects heal with an extremely beautiful result, but require patience (with exposed bone about 1 month per cm). (Fig. 5). After flap surgery, the stitches can usually be removed after one week and the treatment completed after two weeks. Depending on the size of the defect, ps healing takes several weeks or even months. It is helpful during the healing phase to apply collagen wound dressings (e.g. Suprasorb C® for deep defects and the antimicrobial Suprasorb X+PHMB® for more superficial defects). These only need to be changed 1-2× per week, which can often be done by the patient and/or a relative alternating with the physician. Ps heals should be avoided near the edge of the nostril, lower eyelid, and lips.

Complex defects

Defects affecting several esthetic units, for example on the cheek, upper lip and nasal wing, require very great experience for reconstruction. As a rule, the results are best when each aesthetic unit is reconstructed on its own, whether with one or more displacement flaps, with a full-thickness skin graft, or by ps-healing. Extensive defects involving all layers of the nose must be reconstructed several times with the help of pedicled flaps from the forehead, cheek and, if necessary, the nasal mucosa. A strip of ear cartilage from the cavum conchae is usually used to prevent retraction of the nasal margin. If a hematoma in the area of the nostril is to be avoided, a swab is often sewn onto a graft using the “tie-over technique” or a silastic sheet is fixed to a piece of full skin by means of a mattress suture through the nostril, which is left in place for a week. To prevent infections, Floxal® eye ointment or Prontosan Gel® can be pressed under the foil or swab, respectively. Whenever possible, flaps that cause a sulcus to disappear (melolabial, nasofacial) should be avoided. Often, a laterally pedunculated cheek flap can be anchored in depth, at the periosteum of the apertura piriformis, and the nasal flank or wing can be reconstructed separately.

Association

A compression bandage in the head and neck area is difficult to apply. A circular bandage, which is anchored under the chin, can be used for the forehead and scalp. Over the bridge of the nose, a fleece plaster dressing is better fixed if the cheeks are first degreased with benzine and then sprayed with Nobecutan® or Op-Site® spray. Nose flanks and/or medial corner of the eye should be covered with swabs to apply some pressure under the fleece plaster dressing. If necessary, the eye must be closed with an eye bandage for 24 hours to avoid the risk of injuring the conjunctiva or cornea. If there is significant bleeding or an increased risk of post-operative bleeding, the dressing should be changed the next day. In most cases, a smaller cover dressing is then sufficient. Occasionally, placing a piece of Spongostan® or Gelita-Tuft-IT® may be helpful if a pedunculated flap is bleeding on the back.

Take-Home Messages

- Suspect skin lesion: biopsy or shave excision with histologic examination.

- No reconstruction without histological examination.

- Observe own “learning curve”. Refer more complex problems.

- Aggressive, extensive tumors may need to be discussed at the tumor board.

- Polymorbidity, anticoagulation, and dementia also influence the procedure.

- Observe RSTL and avoid traction on lower eyelid, nostril margin and lips.

- Use adequate instrumentation, 30-gauge cannulas and 5-0 suture material.

- Full-thickness skin grafts are simple but often cosmetically suboptimal.

- PS healing is good in some places, but takes several weeks to months.

- Avoid hematoma with drain, flap and compression bandage.

Literature:

- Lösler A: Plastic reconstructive skin tumor surgery in the head and neck region. Elsevier GmbH, Munich, Germany 2019.

- Heppt WJ, et al: Facial plastic surgery skin defects and wound care. IMC International Medical Service Appenzell, Switzerland, 2015.

- Goldman GD, Dzubow LM, et al: Facial Flap Surgery. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc, Vermont, USA, 2013.

- Baker SR: Local flaps in facial reconstruction. Mosby Elsevier, Philadelphia, USA, 2007.

- Kastenbauer ER, Tardy EM, et al: Aesthetic and plastic surgery of the nose, face and auricle, Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, Germany, 1999.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2020; 15(4): 4-8

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2021; 31(6): 10-14