A persistent lymphadenopathy is a clear indication for further histopathological diagnosis. A detailed medical history as well as knowledge of previous diseases, manipulations and drug therapies are essential for a definitive lymphoma diagnosis. There are cases which lie in gray areas in terms of classification. The presence of MYC rearrangements is an undisputed prognostic biomarker in DLBCL, as well as phenotypic co-expression of myc and bcl2 proteins. Response to rituximab therapy is related to CD20 expression. Molecular studies are yielding new genetic predictive parameters for specific response to targeted therapies in lymphoma.

Lymphomas represent the fifth most common group of malignancies in both sexes, accounting for a relative proportion of 5%. Specifically, mature B-cell lymphomas (formerly “non-Hodgkin lymphomas”) show the fastest growing malignancy incidence in the industrialized world after melanoma.

The reasons for this are unknown, but could be related to increasing life expectancy, to the rising incidence of autoimmune diseases and the associated widespread use of (new) immunosuppressants, or to increasing exposure to certain pesticides and herbicides. The incidence of lymphoma is currently about 25 cases/100,000 population/year.

The progress of oncological therapy is clear in lymphomas. The disease-specific 5-year survival rates for the most common nodal lymphomas, such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma (FL), classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL), and B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (B-LBL, nodal equivalent of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia), are approximately 60% (DLBCL) and approximately 80% (the remaining entities), respectively. This explains the high prevalence of lymphoma.

Definition

Lymphomas are defined as malignant, neoplastic diseases of immature or mature B, T, or NK lymphocytes in organs of the lymphatic system (nodal) or outside such organs (extranodal). They may be leukemic or without washout (lymphomas in the narrow sense).

Clinic

Nodal lymphomas present with localized or generalized, persistent (more than three weeks), often progressive lymphadenopathy with or without general (B) symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss), organ involvement, skin changes (pruritus, erythema), or signs of bone marrow insufficiency (anemia, petechiae, tendency to infection).

Persistent lymphadenopathy, especially accompanied by the symptoms mentioned above, is thus a clear indication for further diagnostic workup.

Diagnostics

Tissue-based diagnostics are indispensable in lymphoma, as histopathologic tissue changes are the cornerstones of dignity and entity determination. Based on these changes, conventional light microscopy can be used to differentiate between benign and malignant and the degree of maturation of the affected lymphocytes. Using advanced microscopic in situ methods such as immunohistochemistry (protein expression) or fluorescence in situ hybridization (recurrent chromosomal aberrations), lineage affiliation (B, T, or NK lineage), exact developmental stage (e.g., germinal center B cell), pathological marker expressions (e.g., expression of T cell markers on B cells as in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia [B-CLL]) or existing chromosomal translocation (e.g. t[14;18] at FL) can be determined and an exact diagnosis can be made. This is a basic requirement for specific oncological therapy. In diagnostically difficult cases, DNA can be obtained from the (formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded) material and further analyzed for B- and T-cell clonality, translocations, and point mutations.

Classification

Lymphomas are classified according to the current WHO classification. The overriding principle is integrative diagnosis, which considers the inclusion of histopathologic morphology of the lymphoma, phenotypes (protein expression patterns), genotypes (recurrent chromosomal aberrations), and clinic to be of equal importance in the classification of entities.

The primary separation of lymphomas into Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas has been abandoned. Because of its characteristic morphology, clinical presentation, and excellent response to specific therapies, HL continues as a distinct entity.

New categories: Due to the biological complexity of certain diseases, two so-called “gray zone categories” have been introduced by WHO:

- Unclassifiable B-cell lymphomas with intermediate features between a DLBCL and HL.

- Unclassifiable B-cell lymphomas with intermediate features between a DLBCL and Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL).

Apart from clinical and morphologic overlap between individual entities in both categories, molecular studies show significant overlap in expressed genes between primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphomas and HL on the one hand, and between individual DLBCL and BL on the other.

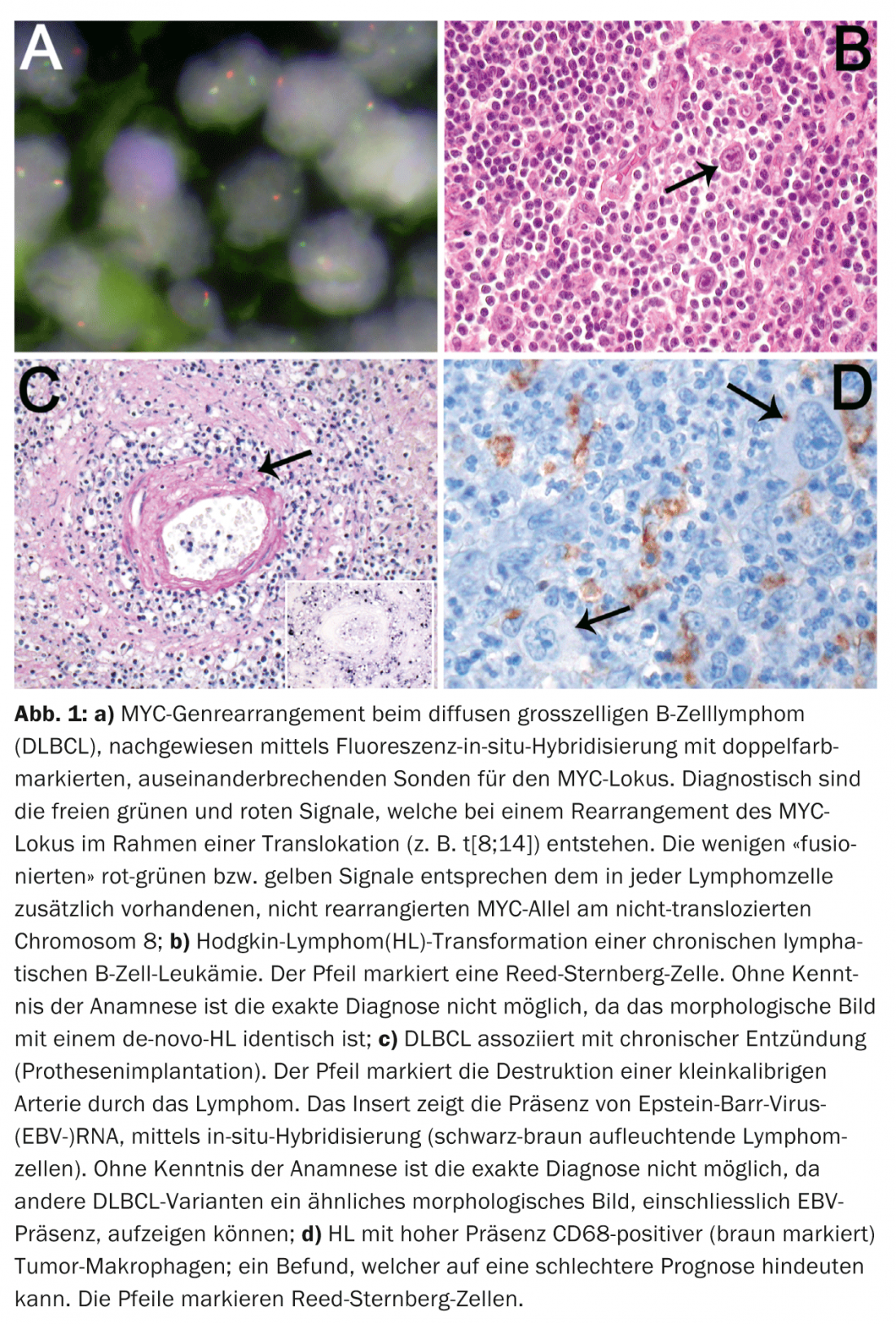

The unfavorable clinical course of highly proliferative DLBCL cases with MYC gene rearrangement (Fig. 1a) further justifies the introduction of such a gray zone category to follow up these cases that have an inadequate response to standard DLBCL therapies in prospective therapeutic trials.

Diagnostic categories based on clinical parameters: In the WHO classification, patient-related context such as age, previous or ongoing drug therapy, especially immunosuppressive therapy, and localization were strongly considered. Four entities are defined by patient age:

- pediatric FL

- pediatric nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL).

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder of childhood.

- EBV-associated DLBCL of the elderly.

The rationale for the introduction of these entities is the association of emergence with immaturity or senescence of the immune system. While the first three of those listed are notably rare, the relative proportion of the latter is 3% of all DLBCL. Although Far Eastern studies suggest a marked aggressiveness of this lymphoma, our data from Central Europe show a particular clinical aggressiveness only in isolated cases.

Reflecting the frequency and heterogeneity of DLBCL, additional clinicopathologic variants were defined in the new classification. For some of these variants, such as DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation (pyothorax, chronic osteomyelitis, infected foreign body implants, i.e. vascular/joint prostheses, chronic skin ulcers, arthritic joints in rheumatoid arthritis), knowledge of the clinic is classificatory essential (Fig. 1b). Since 70% of these lymphomas are associated with EBV and occur largely in elderly patients, differentiation from EBV-associated DLBCL of the elderly is possible only on the basis of anamnestic evidence.

Knowledge of the clinic is also essential for the diagnosis of iatrogenic, immunodeficiency-associated, lymphoproliferative disorders (therapy with immunosuppressants), as well as for the diagnosis of post-transplant lymphoproliferation (organ or allogeneic bone marrow transplantation). Similarly, secondary transformed “small cell B-cell lymphomas” (B-CLL, MZL, FL) can transform into DLBCL, unclassifiable B-cell lymphoma with intermediate features between a DLBCL and a BL, as well as HL. The anamnestic evidence about a previous indolent lymphoma from the group of “small B-cell lymphomas” is crucial for the correct classification of such lesions. This is significant because DLBCL or HL (Fig. 1c) transforming from such B-cell lymphomas have a much more aggressive course than their de novo analogues.

Prognosis and prediction

Numerous studies over the past decade have aimed to establish significant tumor-related prognostic factors in the most common nodal lymphomas such as DLBCL, FL, and HL. However, the known clinical prognostic factors such as the International Prognostic Index (IPI) in DLBCL, the FL International Prognostic Index (FLIPI), and the International Prognostic Score (IPS) in HL were not surpassed by including tumor-related prognostic factors. Except for a few variants of DLBCL that are associated with a rather worse prognosis, such as T-cell- and histocyte-rich DLBCL, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, and intravascular DLBCL, only the detection of MYC rearrangements is an uncontroversial tumor-related prognostic parameter in DLBCL. Three independent recent large studies have demonstrated the prognostically unfavorable role of phenotypic co-expression of the proteins myc and bcl2 (so-called “phenotypic double-hit DLBCL”). Studies in HL and FL showed a prognostic effect of background T cell composition. Recent gene expression studies further demonstrated that signatures of tumor-associated macrophages may substantially influence survival in HL, as reflected morphologically by high levels of tissue macrophages in patients with unfavorable prognosis (Fig. 1d).

In summary, prognostic markers in lymphoma are not yet ready for everyday practice. However, the search for tumor microenvironment-associated prognostic parameters turns out to be promising, especially since this milieu might also be therapeutically manipulable without fear of resistance development by the tumor.

Another area of research is concerned with the establishment of predictive markers, namely biomarkers that indicate response or non-response to therapy. Although clinical trials in establishing the therapeutic anti-CD20 antibody rituximab did not specifically examine CD20 expression, experience shows that only B-cell lymphomas expressing CD20 respond to this therapy. Thus, determination of CD20 expression in lymphoma is an example of a histopathologically determinable predictive marker.

Recent data suggest that specific sensitivity to Bruton kinase inhibitors (e.g., ibrutinib), apoptosis-promoting agents (e.g., obatoclax), and phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors (including mTOR inhibitors such as everolimus) can be predicted based on specific genetic alterations in lymphoid cells.

Prof. Dr. med. Alexandar Tzankov

Prof. Dr. med. Stephan Dirnhofer

Literature:

- Roman E, Smith AG: Histopathology 2011; 58: 4-14.

- Swerdlow SH, et al: WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008.

- Hoeller S, et al: Hum Pathol 2010; 41: 352-357.

- Tzankov A, et al: Mod Pathol 2013; doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013

- Hu S, et al: Blood 2013; 121: 4021-4031.

- Steidl C, et al: N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 875-885.

- Tzankov A, et al: Haematologica 2008; 93: 193-200.

- Rahal R, et al: Nat Med 2014; 20: 87-92.

- Wenzel SS, et al: Leukemia 2013; 27: 1381-1390.

- Pfeifer M, et al: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110: 12420-12425.

InFo Oncology & Hematology 2014; 2(2): 5-7.