Both asymptomatic and symptomatic PAD patients have an increased cardiovascular risk. Early diagnosis, prevention and treatment are therefore crucial. The recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) were updated in 2024. Recently, PAD has become a subchapter of a comprehensive guideline document on peripheral arterial and aortic disease (PAAD).

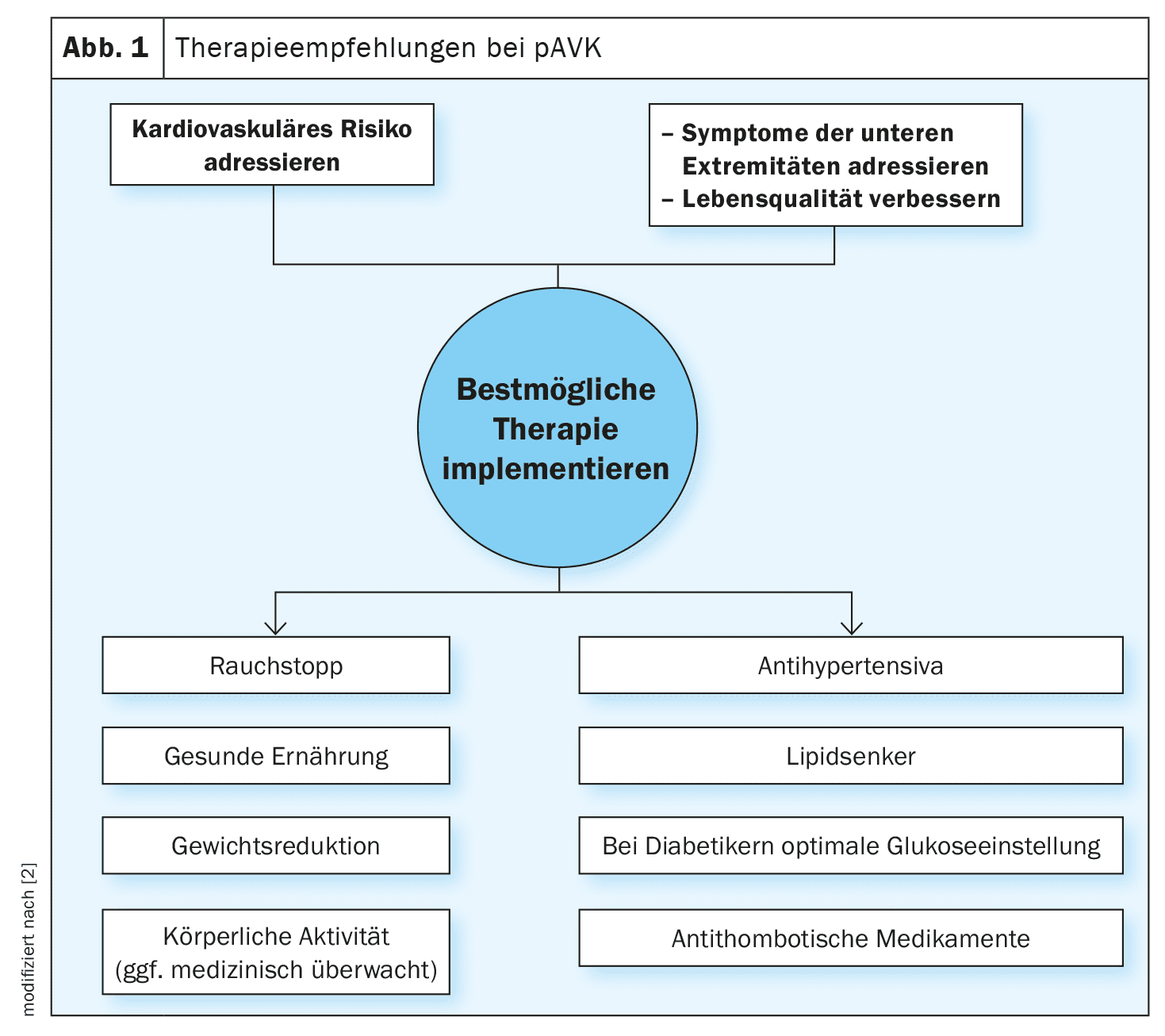

The global prevalence of peripheral arterial and aortic disease (PAAD) is 1.5% and increases with age, affecting 15-20% of those over 70 and 20-30% of those over 80 [1,2]. Patients with aortic disease are at increased risk of peripheral vascular disease and vice versa. A significant proportion of patients are asymptomatic, which is why PAAD screening based on risk factors such as age, family history and other predisposing factors is crucial. PAAD can be diagnosed using non-interventional vascular testing or imaging. The guidelines (box) emphasize that the management of hypertension, hyperlipidemia and diabetes is key to preventing serious complications. In addition to lifestyle factors, drug interventions (e.g. lipid-lowering/blood pressure-lowering/antidiabetic/antithrombotic therapy) may also be indicated to prevent complications. LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) is a central factor in arteriosclerosis, with diabetes and tobacco consumption increasing the risk of PAD by a factor of 2 to 4. Around 20-30% of diabetics have PAD [3,21].

| New ESC guideline on PAAD emphasizes holistic approach The integration of recommendations on the management of peripheral arterial and aortic disease (PAAD) into a single guideline document is intended to reflect the fact that the aorta and peripheral arteries are integral parts of the same arterial system. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has now introduced this update as there have been significant advances in the understanding and treatment of PAAD since the respective guidelines were published in 2014 and 2017. The key recommendations of the 2024 guideline address the chronic nature of PAAD, the importance of early detection and the need for comprehensive treatment strategies. The aim is to achieve coherent and coordinated treatment for different vascular diseases, thereby reducing fragmentation and improving overall treatment outcomes. |

| to [1,2] |

Ankle-brachial index is meaningful

The guideline points out that “peripheral arterial disease” (PAD) or “peripheral arterial occlusive disease” (PAOD) only refers to atherosclerotic disease of the lower extremities. “Patients with PAD have the highest risk of suffering cardiovascular events,” explained Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Zeller, University Heart Center, Freiburg-Bad Krozingen (D) [3]. PAD can be symptomatic or asymptomatic and may or may not be associated with wounds to the limbs. All patients with PAD have a high risk of a major adverse cardiac event (MACE) and cerebrovascular disease. The cumulative 5-year incidence of cardiovascular mortality is 9% in asymptomatic PAD and 13% in symptomatic patients. The ankle-brachial index (ABI) is the proposed first non-invasive diagnostic test to confirm reduced blood flow status of the lower limbs and must be reported separately for each leg. An ABI ≤0.90 confirms the diagnosis of PAD.

Screening for coronary heart disease is mandatory

In addition to assessing limb perfusion, the ABI serves as a surrogate marker for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. A typical symptom of PAD is pain when walking, which subsides at rest. Evaluation of walking disability and functional status is mandatory. And all PAD patients should be screened for the presence of coronary heart disease. “Screening for coronary heart disease is essential in these patients,” said Prof. Zeller [3]. Duplex ultrasound can be used to distinguish atherosclerotic (including subclinical) from non-atherosclerotic lesions. Cardio-CT is considered the most important imaging procedure for the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment planning of aortic diseases (for acute aortic syndrome, the sensitivity is 100% and the specificity 98%). Cardio-MRI is suitable for a comprehensive assessment of the aorta, including shape, diameter and tissue characteristics. In PAD patients with coexisting diabetes and/or infections, it should be remembered that wound healing may be impaired, which is associated with an increased risk of amputation. Therefore, the risk of amputation in such patients should be systematically assessed using the classification for wounds, ischemia and foot infections.

Structured walking training recommended

Recently, a consensus paper on exercise and PAD was published in the European Heart Journal [15]. Physical activity is an important lifestyle intervention in PAD to improve symptoms and promote quality of life. In patients with symptomatic PAD, improvements in six-minute walk distance (6MWD), health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and cardiorespiratory fitness have been demonstrated. According to the speaker, regular walking training, possibly in a group under expert guidance, is most suitable [3]. In the case of intermittent claudication, structured walking training three times a week for 30-60 minutes has proven effective. Symptomatic patients should undergo a medical examination before starting exercise and, if possible, complete medically supervised training sessions. In addition, it is recommended that smokers stop smoking and that hypertensive patients lower their blood pressure. For most adults, a systolic target value of 120-129 mm Hg should be aimed for, provided the therapy proves to be well tolerated. If this target value appears unattainable, the ALARA principle (“As Low As Reasonably Achievable”) can be implemented. There is a IIa recommendation for the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in the first line. With regard to lipid management, the current guideline advises aiming for an LDL cholesterol value of <55 mg/dl (1.4 mmol/l) if possible.

Consider antithrombotic therapy for symptomatic PAD

In patients with symptomatic PAD, antithrombotic therapy improves the cardiovascular prognosis [4–8]. For these patients, there is a class Ia recommendation for antiplatelet therapy with aspirin (75-160 mg, 1× daily) or clopidogrel (75 mg, 1× daily) to reduce the risk of MACE [4–6]. Studies suggest that clopidogrel may have a modest advantage over aspirin [9,10]. In the EUCLID (Examining Use of tiCagreLor In peripheral artery Disease) trial, antithrombotic monotherapy with ticagrelor did not show superior benefit in reducing MACE or major bleeding events compared to clopidogrel. Dual antithrombotic therapy with aspirin and rivaroxaban (2.5 mg, 2× daily) is more effective than aspirin alone in patients with PAD, as it reduces the incidence of stroke (MACE) and acute limb ischemia; however, it is associated with an increased risk of major bleeding. Antithrombotic therapy should not be systematically administered to patients with asymptomatic PAD. Although patients with PAD have a very high cardiovascular risk, a study investigating the effect of antiplatelet agents in asymptomatic patients with an ABI ≤0.95 showed no effect on MACE or revascularization [11,12]. Another study in patients with an ABI ≤0.99 and diabetes also showed no difference in MACE or amputations [13]. However, these data were not designed for subgroup analysis and do not rule out the possibility that aspirin may have a benefit in patients at increased risk of cardiovascular events.

Check indication for revascularization

In patients with symptomatic PAD and impaired PAD-related quality of life, revascularization can be considered after three months of the best possible drug treatment and exercise therapy (IIb recommendation). It is recommended to adapt the mode and type of revascularization to the anatomical location of the lesion, the lesion morphology and the general condition of the patient. For patients undergoing endovascular revascularization, supervised exercise therapy is recommended as an accompanying measure. There is evidence from individual studies that dual platelet inhibition over a period of 1-3 months is beneficial after endovascular revascularization therapy [16,17]. A combination of aspirin 100 mg and rivaroxaban (2.5 mg, 2× daily) after revascularization showed a moderate but significantly lower incidence of MALE and MACE compared to aspirin alone, without an increase in major bleeding due to thrombolysis in myocardial infarction, but with an increase in major bleeding according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, especially when clopidogrel was given for >1 month [6,18,19]. It is recommended that patients with PAD undergo regular follow-up examinations, i.e. at least once a year, to assess clinical and functional status as well as adherence to therapy, limb symptoms and all cardiovascular risk factors, using duplex ultrasound if necessary. PAD is one of the clinical risk factors included in the CHA2DS2-VASc score – a diagnostic tool to assess the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) [20]. The prevalence of AF in patients with PAD is around 12%.

Congress: swissESCupdate.24

Literature:

- “New ESC Guidelines combine peripheral arterial and aortic diseases for first time, emphasizing interconnectivity of whole arterial system”, European Society of Cardiology (ESC), 30 Aug 2024.

- Mazzolai L, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur Heart J 2024; 45(36): 3538-3700.

- “2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases”, Prof. Dr. Thomas Zeller, Swiss ESC Update 2024, Basel, 05.09.2024

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002; 324: 71-86.

- De Carlo M, et al: Efficacy and safety of antiplatelet therapies in symptomatic peripheral artery disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2021; 19: 542-555.

- Willems LH, et al: Antithrombotic therapy for symptomatic peripheral arterial disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Drugs 2022; 82: 1287-1302.

- Katsanos K, et al: Comparative efficacy and safety of different antiplatelet agents for prevention of major cardiovascular events and leg amputations in patients with peripheral arterial disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0135692.

- Basili S, et al: Comparison of efficacy of antiplatelet treatments for patients with claudication. A meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost 2010; 103: 766-773.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomized, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet 1996; 348: 1329-1339.

- 10. Berger JS, et al: Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral artery disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA 2009;301: 1909-1919.

- Dorn A, et al: Low and high ankle-brachial index are both associated with mortality in German nursing home residents-the five-year follow-up of the “allo-study” Cohort. J Clin Med 2023; 12: 4411. doi: 10.3390/jcm12134411

- Fowkes FG, et al: Aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular events in a general population screened for a low ankle brachial index: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010; 303: 841-848.

- Belch J, et al: The prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomized placebo controlled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ 2008; 337: a1840.

- Bowman L, et al: Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 1529-1539.

- Mazzolai L, et al: Exercise therapy for chronic symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Eur Heart J 2024; 45: 1303-1321.

- Strobl FF, et al: Twelve-month results of a randomized trial comparing mono with dual antiplatelet therapy in endovascularly treated patients with peripheral artery disease. J Endovasc Ther 2013; 20: 699-706.

- Tsai SY, et al: Mono or dual antiplatelet therapy for treating patients with peripheral artery disease after lower extremity revascularization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022; 15:596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15050596.

- Bonaca MP, et al: Rivaroxaban in peripheral artery disease after revascularization. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1994-2004.

- Hiatt WR, et al: Rivaroxaban and aspirin in peripheral artery disease lower extremity revascularization: impact of concomitant clopidogrel on efficacy and safety. Circulation 2020; 142: 2219-2230.

- Olesen JB, et al: Am J Med 2012;125: 826.e13-23.

- Criqui MH, Aboyans V: Circ Res 2015;116: 1509-1526.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(11): 28-29 (published on 22.11.24, ahead of print)