The Autoimmune blistering diseases Task Force of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) recently issued new recommendations for the treatment of bullous pemphigoid. The consensus expert opinion is based on current clinical evidence regarding diagnostic methods and therapeutic strategies.

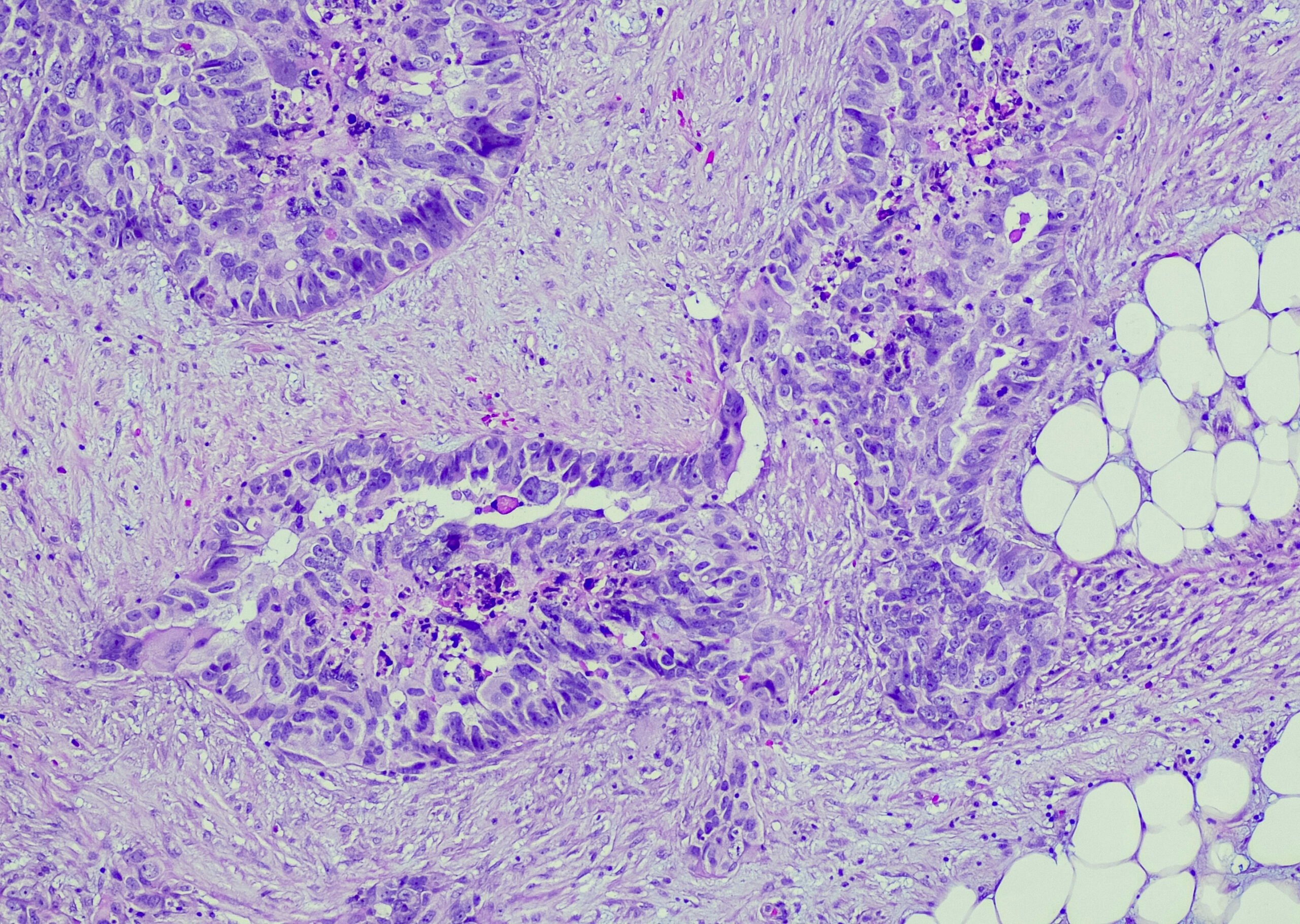

Blistering autoimmune diseases are rare but life-threatening diseases of the skin and mucous membranes. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common bullous autoimmune dermatosis. Autoantibodies form against hemidesmosomes of basal keratinocytes with subepidermal blistering [1]. The disease typically occurs in elderly patients. Localized or generalized bullous lesions on inflammatory reddened or normal skin are characteristic [2]. A subgroup of patients develops excoriations, prurigo-like lesions, and eczematous and/or urticarial erythematous lesions only. Almost all patients suffer from pronounced pruritus [3]. Bullous pemphigoid is a disease associated with high morbidity and significantly affects the quality of life.

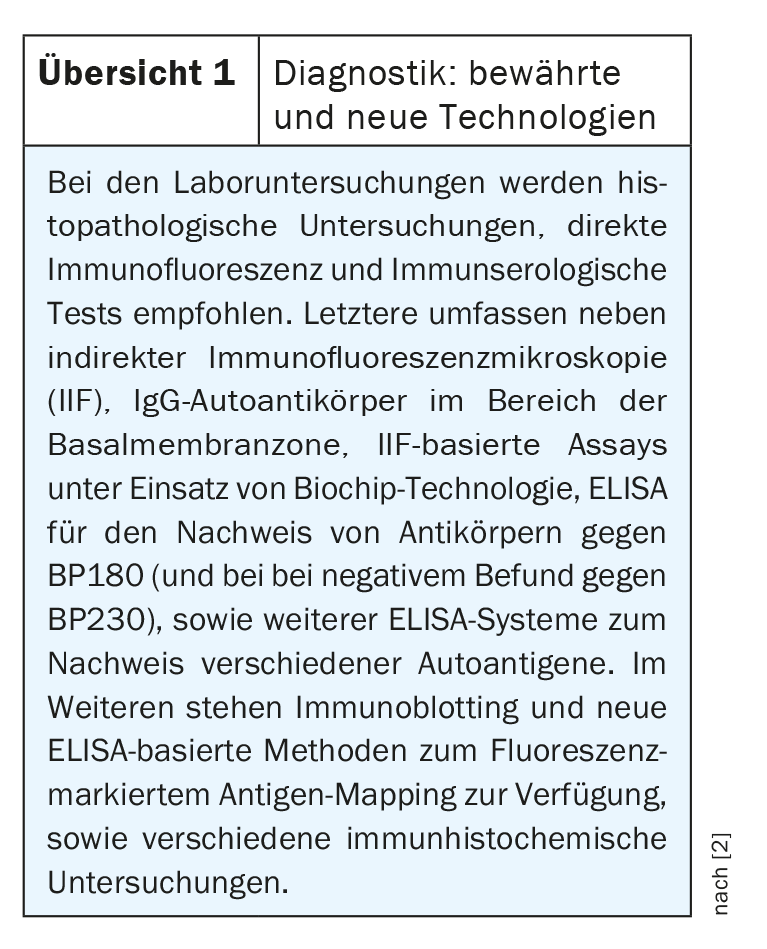

In the updated guideline, the diagnostic steps are described in detail with reference to the latest findings [2]. Nowadays, a large arsenal of state-of-the-art technologies is available.

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy and ELISA

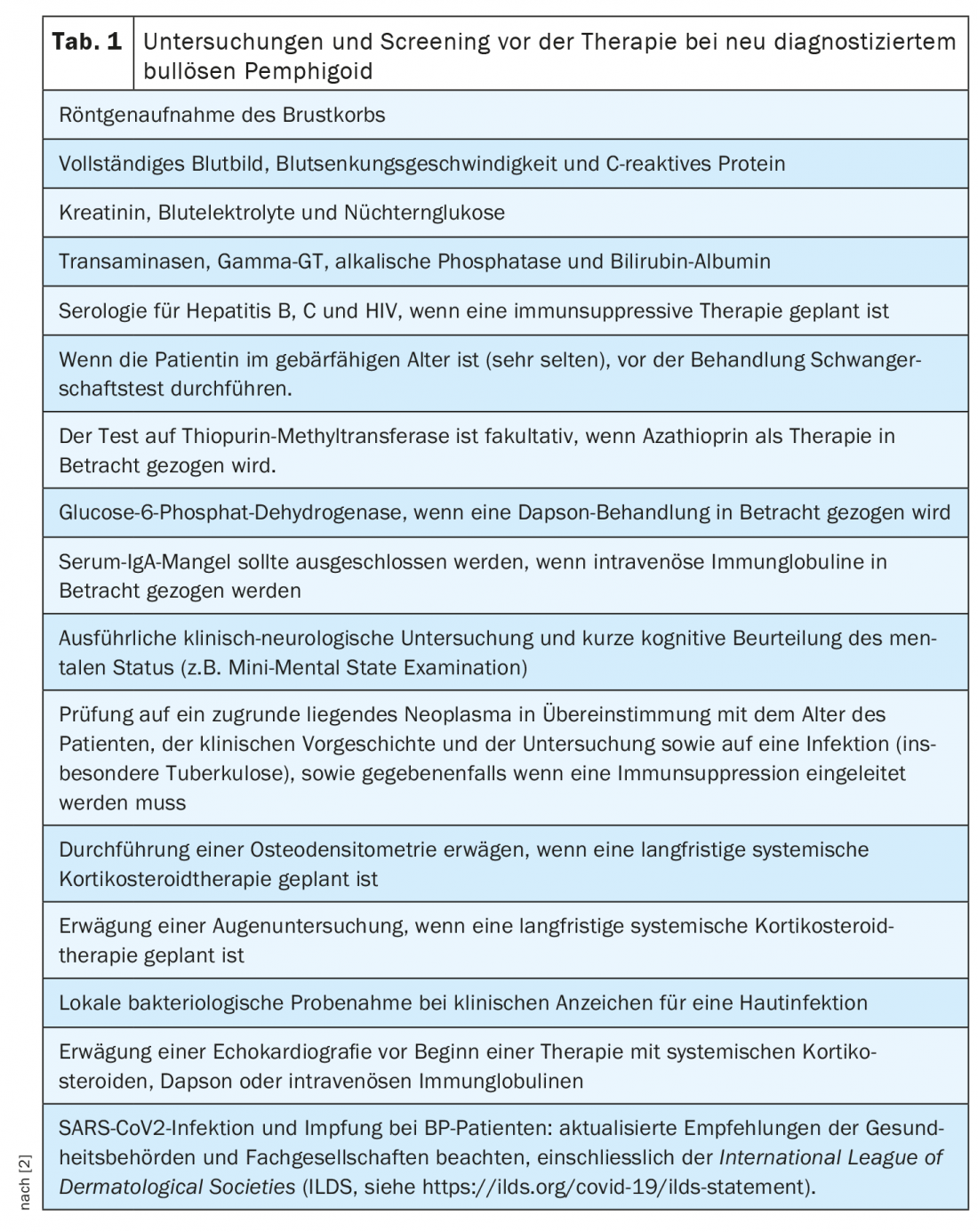

In addition to history and physical examination – including recording of the BPDAI (“Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index”), quality of life and any comorbidities present – there is a wide range of laboratory tests and other immunopathological test procedures that can be used (overview 1) [2]. The diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid is based on a combination of clinical features and positive findings on direct and indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. ELISA and indirect immunofluorescence microscopy can detect circulating autoantibodies. Analysis of linear deposits along the dermo-epidermal boundary is a reliable practical approach to differentiate bullous pemphigoid from other forms of pemphigoid. When choosing the appropriate treatment option, concomitant diseases such as hypertension must also be taken into account. The preliminary investigations recommended in patients with newly diagnosed bullous pemphigoid are summarized in Table 1 .

Topical clobetasol propionate as the main treatment component

Consensus recommendations advise the use of high-potency topical corticosteroids whenever possible [2]. For this purpose, clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream is recommended, both for localized, limited and moderate infestation, each in a dosage of 20-30 g daily. In severe cases, a dose of 30-40 g/d may be used, initially once or twice daily over the entire integument, including healthy skin areas, with exclusion of the face. Alternatively, oral prednisolone may be used. In prospective observational studies, prednisolone at an initial dose of 0.5 mg/kg/d on day 21 resulted in disease control in about two-thirds of patients with mild-to-moderate bullous pemphigoid, and in severe disease in only 46% of cases [11]. Disease control is defined as a state in which no new lesions or itch symptoms appear and existing lesions heal. In severe cases, prednisolone 1 mg/kg/d has been shown to be effective, but this high-dose therapy is associated with higher risk of side effects and mortality compared with large-surface topical therapy with clobetasol propionate 0.05%. Therefore, prednisolone 1 mg/kg/d is not recommended as initial treatment [2].

Immunosuppressants such as methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or mycophenolic acid may be used in cases of contraindications or inadequate response to corticosteroids. The use of doxycycline and dapsone is controversial, and is mainly limited to adjuvant use in combination with topical corticosteroids.

As an accompanying measure to drug therapy, the use of antiseptic bath additives is recommended. If extensive erosive lesions are present, they can be covered with dressings-preferably nonadherent ones-to reduce bacterial superinfection and pain and promote healing.

Biologics as add-on or monotherapy

In difficult-to-treat cases of bullous pemphigoid, the use of biologics may be considered as a sole or additional treatment option, according to guidelines. Factors to be considered include clinical characteristics, previous course, treatment response, and contraindications to standard treatment. Biologics target proinflammatory cytokines and other cellular targets that contribute to tissue damage in bullous pemphigoid.

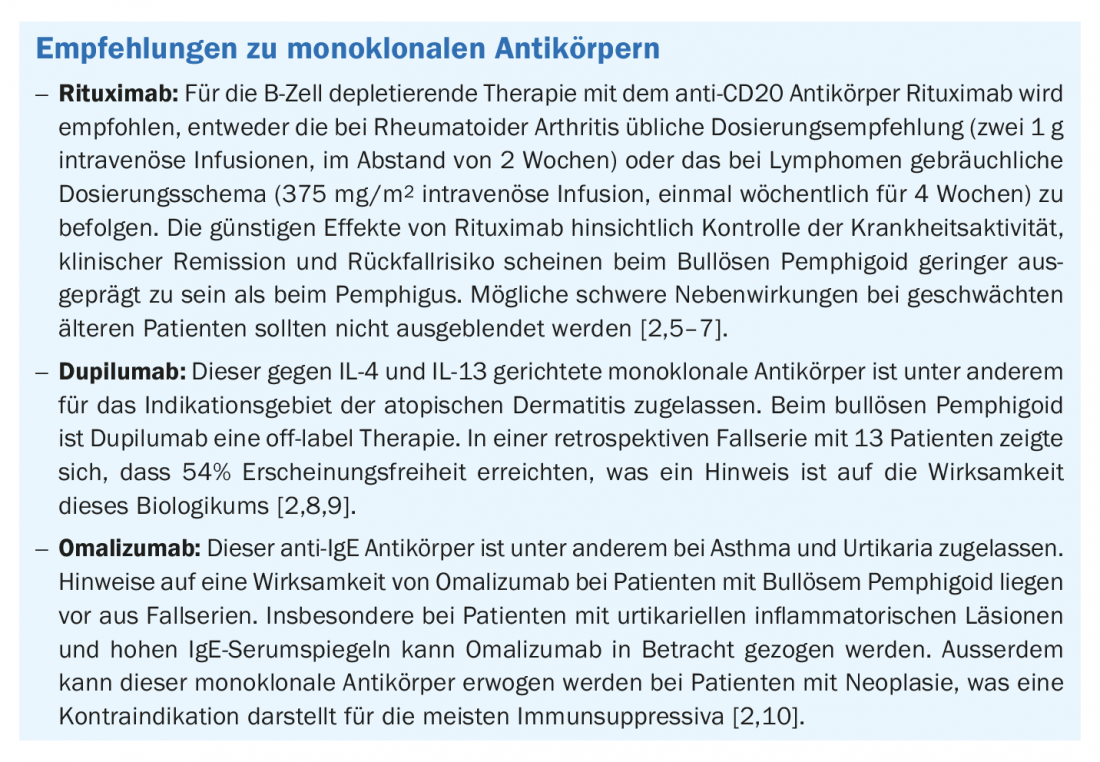

Potentially effective monoclonal antibodies include rituximab (anti-CD20), omalizumab (anti-IgE), and dupilumab (anti-IL-4/-13). The expert recommendations in this regard are summarized in the box [2]. Several other therapeutic approaches are also being explored, including blockade of IL-17, IL-12/-23, IL-5Ra [4]. Moreover, there is empirical evidence that in refractory cases, the use of intravenous immunoglobulin (2 g/kg/d) as an add-on is effective, although potentially severe side effects in elderly patients should be considered.

Monitoring of the course of therapy

Bullous pemphigoid carries risks of complications related to the disease itself on the one hand, but also related to therapy-related side effects on the other hand. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of therapy, regular follow-up examinations are recommended [2]. The frequency of follow-up appointments depends on several factors. Until disease control is achieved, controls are recommended at 1-2 week intervals, then at four week intervals for three months, then every 2-4 months at the end of treatment.

Literature:

- Joura MI, et al: Geriatric Dermatology. Z Gerontol Geriat 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-021-02006-2, (last accessed Aug 19, 2022).

- Borradori L, et al: Updated S2 K guidelines for the management of bullous pemphigoid initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 Jun 29. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18220. epub ahead of print.

- UKSH: Autoimmune Dermatoses, www.uksh.de/dermatologie-luebeck

- Clinicaltrials.gov: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2, (last accessed Aug. 19, 2022).

- Schmidt E, et al: Rituximab in autoimmune bullous diseases: mixed responses and adverse effects. Br JDermatol 2007; 156: 352-356.

- Hall RP 3rd, et al: Association of serum B-cell activating factor level and proportion of memory and transitional B cells with clinical response after rituximab treatment of bullous pemphigoid patients.

- J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133: 2786-2788.

- Joly P: French study group on auto immune bullous skin d, the French network of rare diseases in D. incidence and severity of COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune blistering skin diseases: a nationwide study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 86: 494-497.

- Abdat R, et al: Dupilumab as a novel therapy for bullous pemphigoid: a multicenter case series. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83: 46-52.

- Seyed Jafari SM, et al: Case report: combination of Omalizumab and Dupilumab for recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid. Front Immunol 2020; 11: 611549.

- Fairley JA, et al: Pathogenicity of IgE in autoimmunity: successful treatment of bullous pemphigoid with omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 123: 704-705.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2022; 32(4): 31-32