Atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained arrhythmia. The prevalence in the general population is 1.5-2% [1]. With a fivefold increased risk of stroke and threefold increased risk of cardiac decompensation, AF is a common cause of hospitalization and associated with increased morbidity and mortality [2]. How does the diagnosis proceed and what can be achieved by means of anticoagulation and rhythmization? The following article aims to clarify these questions.

The diagnosis of AF requires documentation of either an absolute arrhythmia without P waves for 30 seconds on ECG monitoring or on a 12-lead ECG [3], so ECG documentation is mandatory. Depending on the duration of the episode of atrial fibrillation, it is referred to as paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent atrial fibrillation. Early diagnosis helps prevent complications of atrial fibrillation. As atrial fibrillation becomes more common with age, screening by pulse palpation is recommended in all patients over 65 years of age. If an irregular pulse is detected, a resting ECG should be performed to confirm the diagnosis or to determine the cause of the irregular pulse. be written to differentiate from other arrhythmias (e.g., extrasystole or atrial flutter) [2].

Anticoagulation

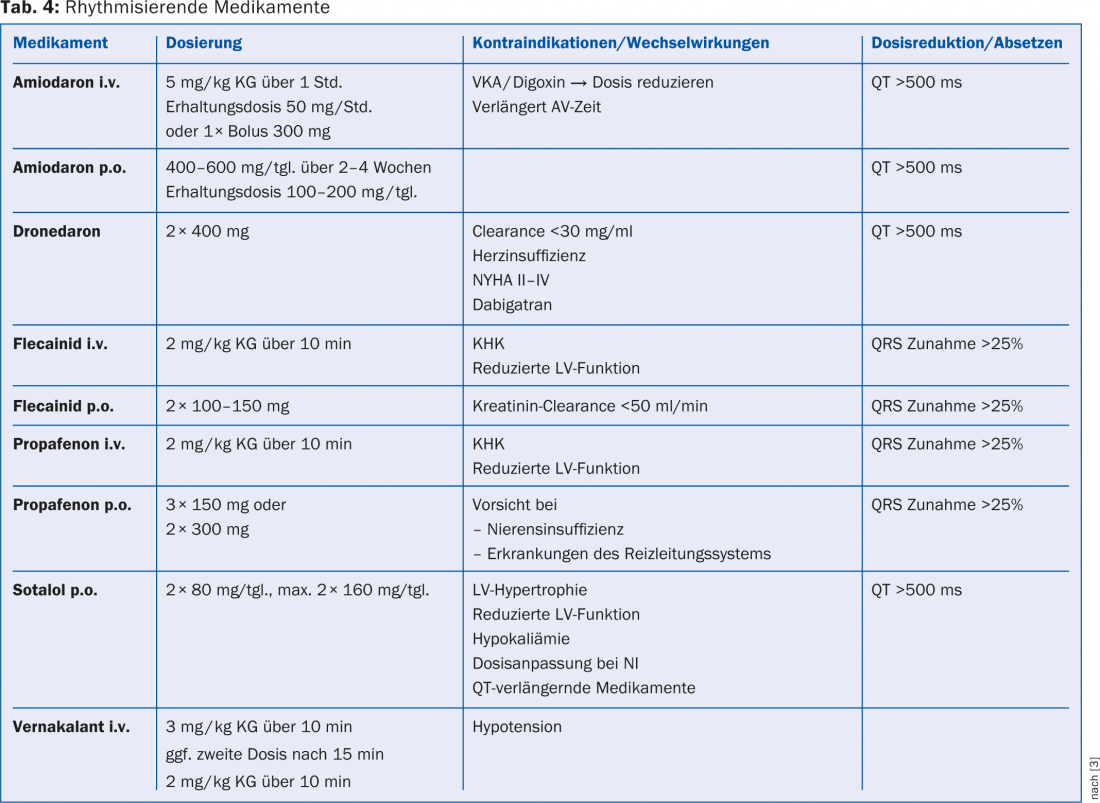

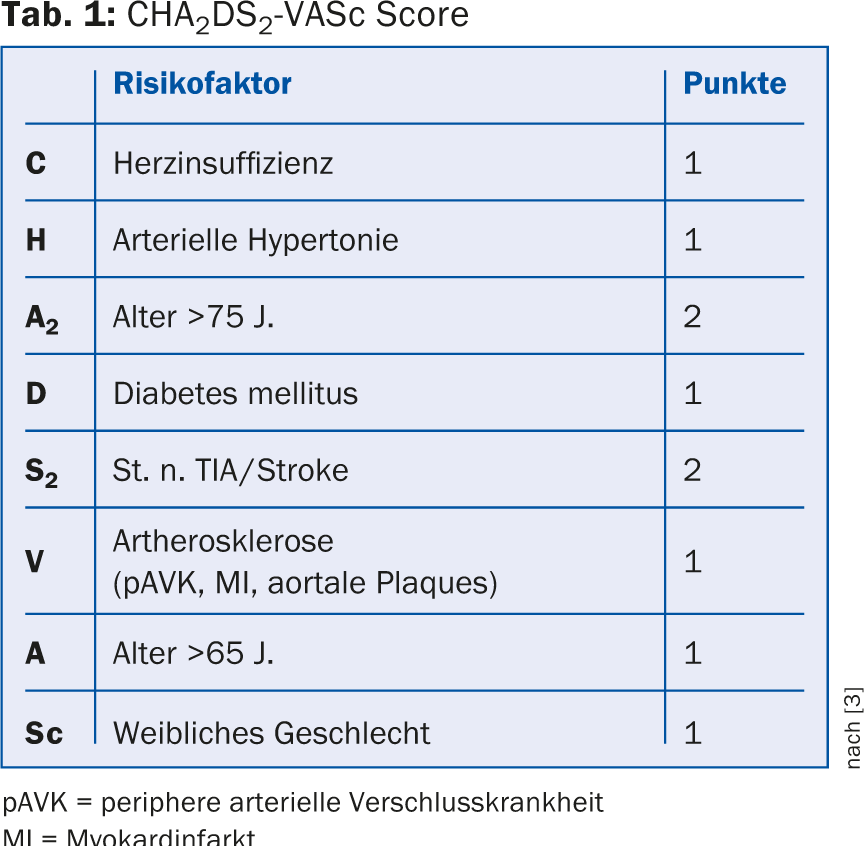

The indication for oral anticoagulation (OAC) in AF is according to the CHA2DS2-VASc score (Table 1), with all patients with ≥1 point requiring OAC [3]. In patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 points or women younger than 65 years with no other risk factors, the risk of embolism is so low that anticoagulation should not be used [2]. Antiplatelet agents are currently no longer recommended for embolic prophylaxis. In clinical practice, antiplatelet agents are occasionally used instead of OAK in elderly, fragile patients with an increased tendency to fall for fear of intracranial hemorrhage. However, these patients in particular are also at high risk of ischemic stroke, from which OAK provides better protection [3,4]. For example, in the AVERROES trial, apixaban was shown to be significantly superior to acetylsalicylic acid in the prophylaxis of ischemic stroke [5]. In addition, no significant difference in the incidence of intracranial hemorrhage has been demonstrated to date with antiplatelet agents compared with vitamin K antagonists [6]. Thus, antiplatelet agents should be used for embolic prophylaxis exclusively in patients who refuse any other form of OAK [2].

The individual risk of bleeding can be calculated using various scoring systems, e.g. the HASbled score (Tab. 2). However, an elevated bleeding score should not automatically be considered a contraindication for OAK. Rather, if the risk of bleeding is high, all treatable risk factors of bleeding should be consistently addressed, e.g., cessation of arterial hypertension, switching to new anticoagulants (NOAKs) if INR values are labile, discontinuing co-medication with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antiplatelet agents unless absolutely necessary.

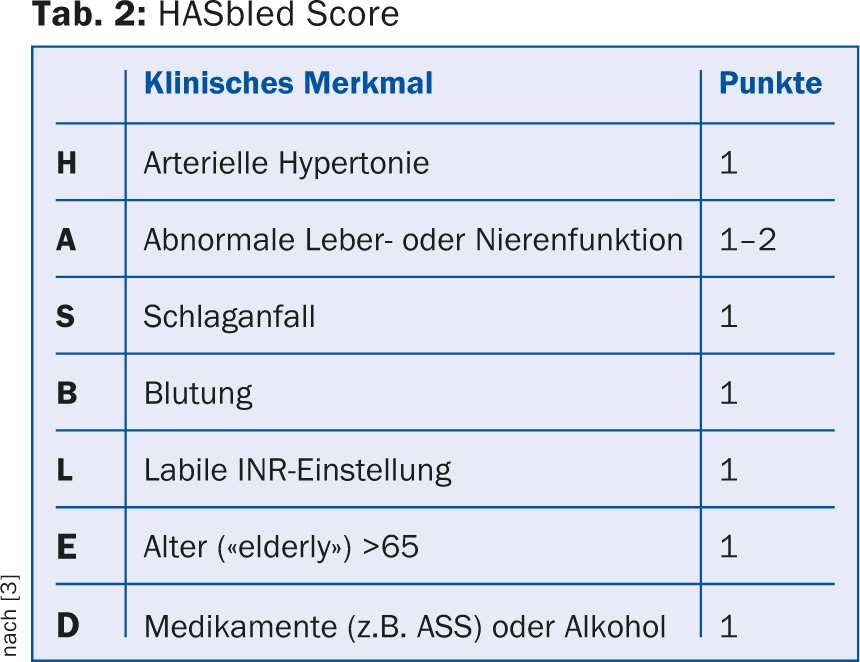

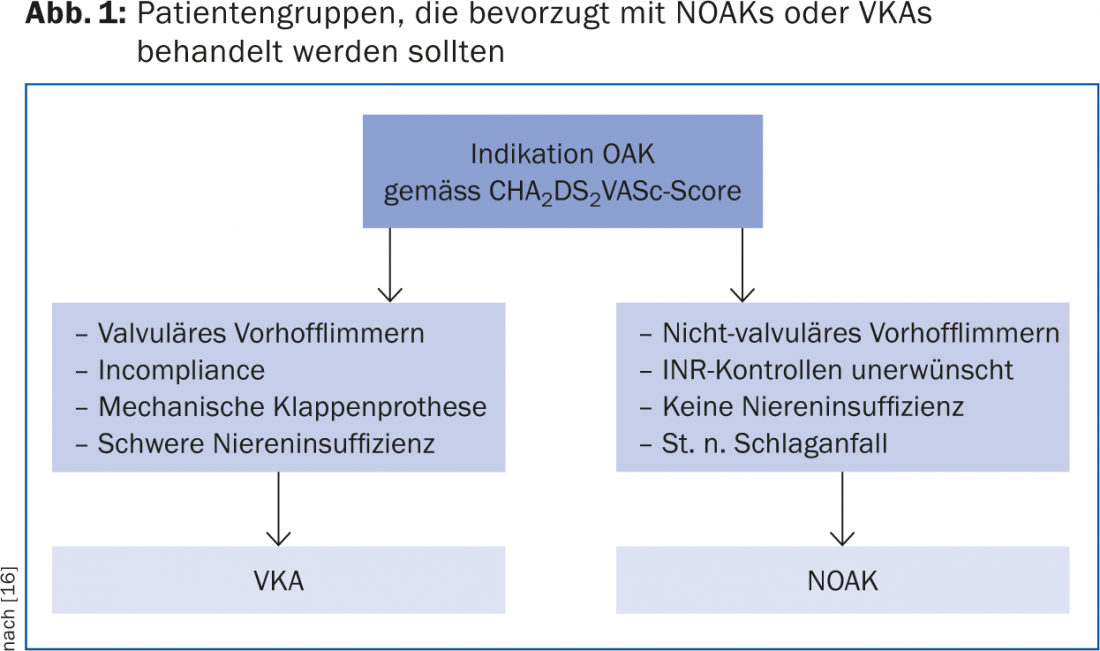

Vitamin K antagonists (VKA) and NOAK: The vitamin K antagonists acenocoumarol (Sintrom®) and phenprocoumon (Marcoumar®) are most commonly used in Switzerland and are so far also the only option for anticoagulation in mechanical valve prostheses, valvular atrial fibrillation and in patients with severe renal insufficiency. For embolic prophylaxis in nonvalvular AF, all three NOAKs (rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and apixaban) were noninferior to VKAs in the large phase III clinical trials and also had a better safety profile. Above a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 points, all three NOAKs were even superior to VKAs in terms of prophylaxis of ischemic stroke and incidence of intracranial hemorrhage [2], which is why they are currently recommended as the preferred form of anticoagulation [7]. Characteristics of each NOAK and key drug interactions are listed in Table 3. Figure 1 provides an overview of suitable patient populations for NOAKs or VKAs.

Atrial ear occlusion: more than 90% of all thrombi in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation originate in the left atrial ear [8]. There are options for both surgical and interventional atrial ear closure. Retrospective and observational studies have provided inconsistent results on surgical atrial appendage closure [2]. Two different closure systems are available for interventional atrial ear closure, the Watchman® device and the Amplatzer Cardiac Plug®, which are placed transseptally from the right atrium into the left atrial ear. Prospective randomized trials are currently underway (PROTECT AF, PREVAIL). Given the current data, atrial appendage closure should be evaluated only in the presence of increased thromboembolic risk and a concomitant contraindication to OAK [2].

Rhythmization or frequency control?

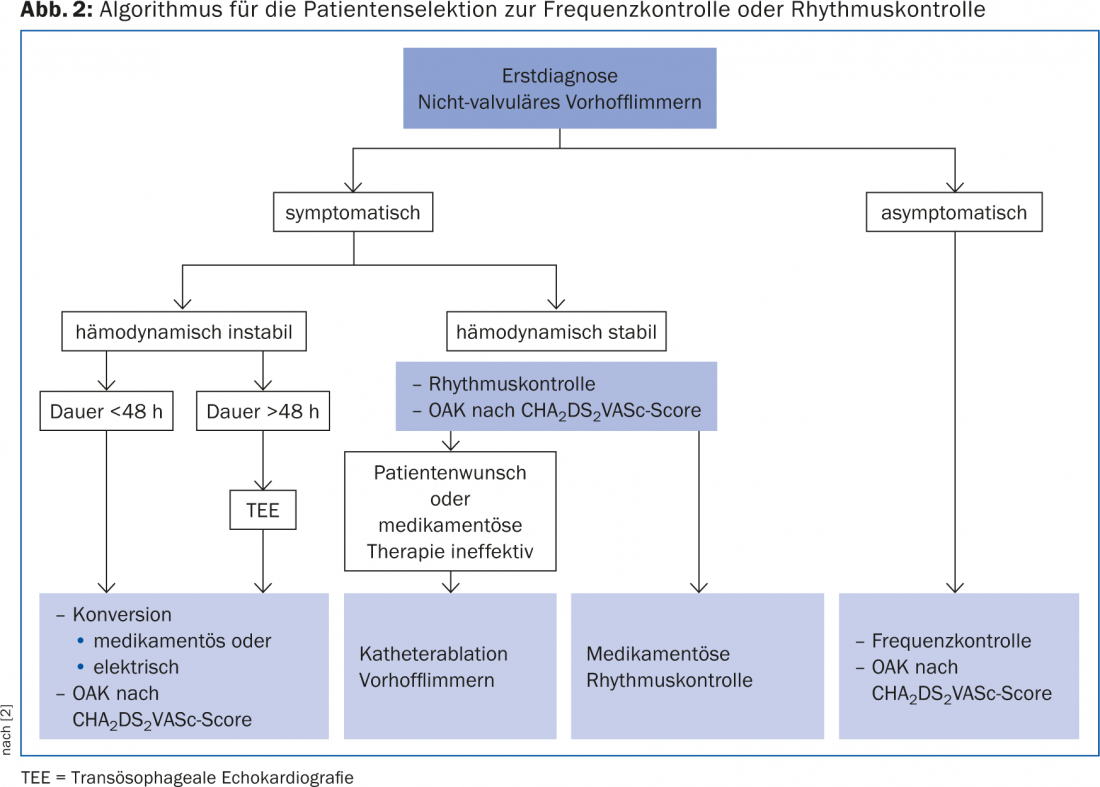

To date, no significant difference in mortality or stroke rate has been found between patients with rate or rhythm control [9]. Whether frequency or rhythm control should be attempted in individual cases depends to a large extent on the respective symptoms and the patient’s willingness to take a permanent medication that may have side effects or to accept an intervention. Figure 2 shows a possible algorithm for the therapy decision on rhythm or frequency control.

Symptoms of atrial fibrillation: The typical atrial fibrillation symptoms are caused by altered hemodynamics. Irregular ventricular filling leads to palpitations and peripheral pulse deficit. Loss of atrial contraction along with shortened ventricular filling in tachycardia can result in a 5-15% decrease in “cardiac output,” causing dyspnea, power intolerance, hypotension, and dizziness to presyncope. Patients with reduced LV compliance (e.g., LV hypertrophy in arterial hypertension or severe aortic valve stenosis) or preexisting severe heart failure tolerate these hemodynamic changes particularly poorly. Shortened diastole during tachycardia decreases coronary flow and may cause AP symptoms, especially in the presence of preexisting coronary sclerosis [3]. All of the symptoms listed here may also be the initial manifestation of atrial fibrillation and, if unexplained, should lead to an ECG diagnosis.

Frequency control: Many symptoms of atrial fibrillation can be minimized with good frequency control. In addition, tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy may occur with sustained ventricular rates >120 bpm (beats per minute = heart rate). Normalization of heart rate usually leads to recovery of LV function [10]. Initially, a resting rate <110/min should be aimed for. If AF remains symptomatic, stricter rate control <80 bpm at rest and <110 bpm under load should be sought [3]. To verify the safety and effectiveness of rate control, 24h ECG monitoring should be performed after adjusting therapy. In younger patients, beta-blockers and nondiydropyridine-type calcium antagonists are preferable because they regulate heart rate at rest and during exercise [3]. Caution should be exercised in patients with preexcitation, which may not be visible on 12-lead ECG. Administration of bradycardic drugs slows AV node conduction, but does not affect atrial conduction. Thus, if an accessory pathway is present, unrestrained conduction of fast atrial frequencies to the ventricles may occur [3].

AV node ablation: In AV node ablation, the AV node is obliterated under catheter control after implantation of a pacemaker, thus inducing total AV block. In patients with symptomatic AF who fail to achieve rate control even with combination drug therapy, AV nodal ablation is a definitive and reliable treatment option. It leads to an improvement in quality of life and is associated with an increase in LV function [11].

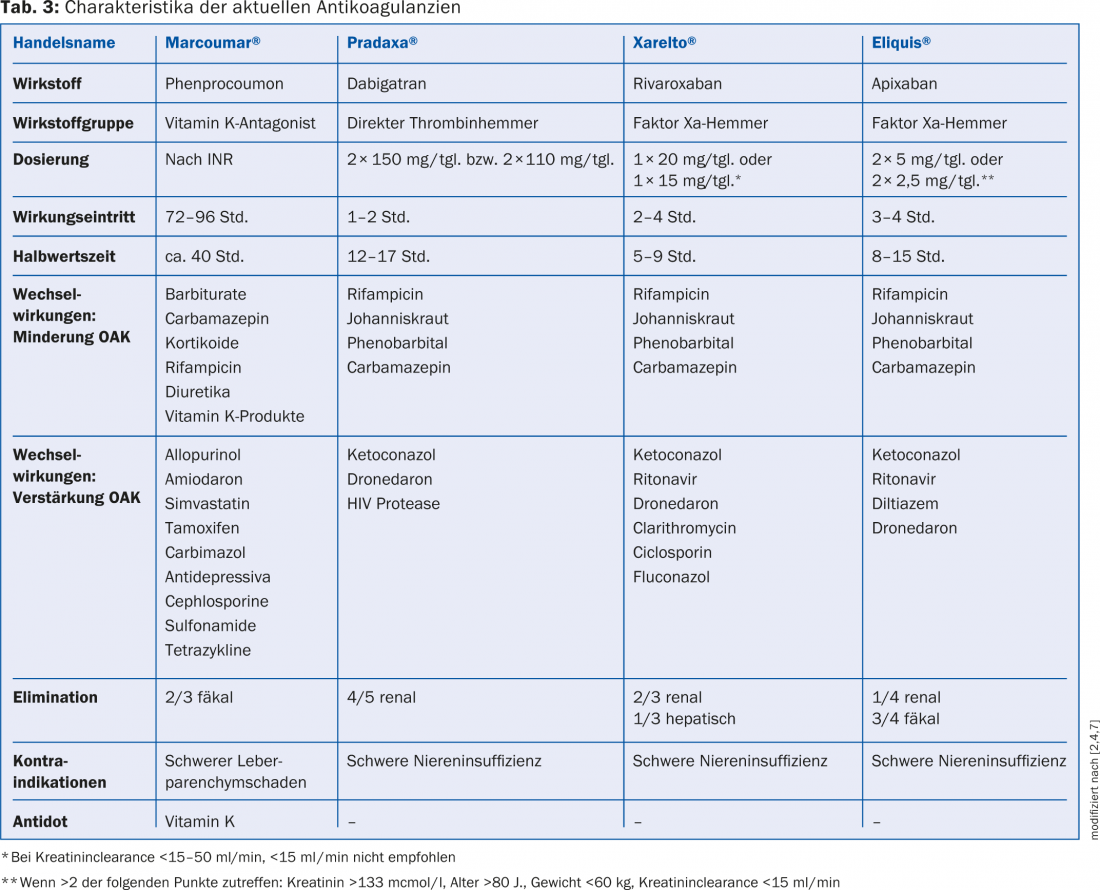

Indications for rhythm control: If a patient is symptomatic even under strict rate control, rhythm control should be sought. In the acute situation of hemodynamic instability, this can be achieved by cardioversion. For long-term therapy, catheter ablation or continuous antiarrhythmic drug therapy are available. If atrial fibrillation exists <48 h, therapy can be started without delay. However, if the CHA2DS2-VASc score is ≥1, there is an indication to start therapeutic anticoagulation simultaneously. If the atrial fibrillation persists >48 h, intracardiac thrombi must be excluded by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or therapeutic anticoagulation must be performed for three weeks prior to initiation of rhythmizing therapy [3]. Regardless of the chosen method of arrhythmia control, ECG monitoring should be performed periodically to check the success of therapy [3]. An overview of the drugs and respective dosages that are suitable for rhythmization is provided by Table 4. If rhythm-regulating therapy is favored over rate control, it should be started as soon as possible after diagnosis of AF, because preservation of sinus rhythm becomes more difficult the longer AF has been present [12,13].

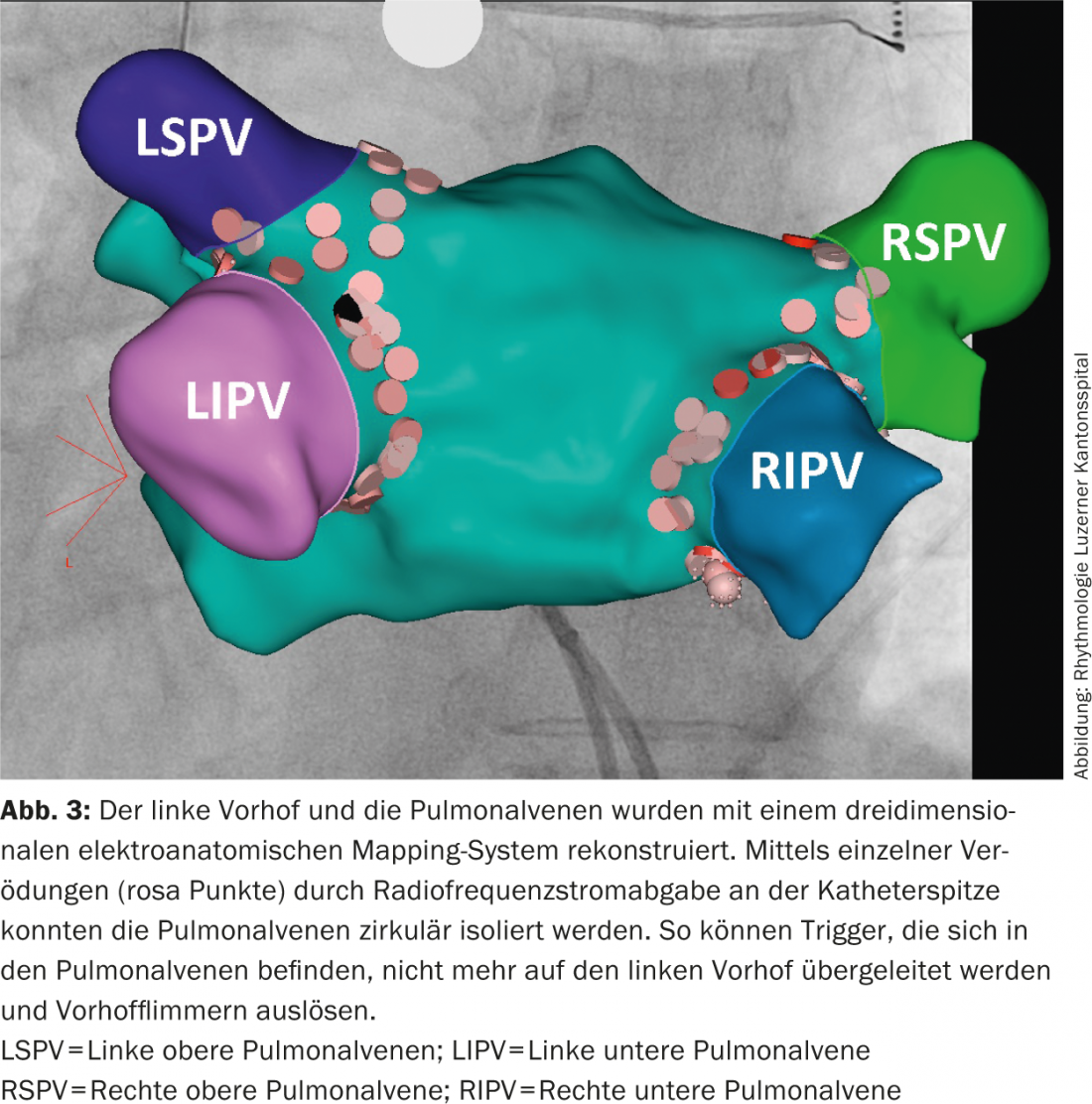

Long-term drug therapy vs. ablation: In symptomatic patients with AF, catheter ablation can be offered as first-line therapy as an alternative to drug therapy with antiarrhythmic drugs (Fig. 3) [2]. When atrial fibrillation ablation is performed at an experienced center, more patients have stable sinus rhythm after catheter ablation than with long-term antiarrhythmic therapy and report better quality of life [14,15]. Catheter ablation is also a good alternative in case of failure or intolerance of antiarrhythmic therapy. Ablation is an effective therapy especially in patients without structural heart disease and atrial fibrillation that is only paroxysmal or persistent for less than one year.

Literature:

- Heeringa J, et al: Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 949-953.

- Camm AJ, et al: 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. An update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2719-2747.

- Camm AJ, et al: Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).European Heart Rhythm Association; European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. Eur Heart J 2010 Oct; 31(19): 2369-2429.

- Van Walraven C, et al: Effect of age on stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke 2009; 40: 1410-1416.

- Coppens M, et al: Efficacy and safety of apixaban compared with aspirin in patients who previously tried but failed treatment with vitamin K antagonists: results from the AVERROES trial. Eur Heart J 2014 Jul 21; 35(28): 1856-1863.

- Mant J, et al: Warfarinvversus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community populationvwith atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of thevAged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 370: 493-503.

- Heidbuchel H, et al: EHRA practical guide on the use ofnew oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: executive summary. European Heart Journal 2013; 34: 2094-2106.

- Watson T, Shantsila E, Lip GY: Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in atrial fibrillation: Virchow’s triad revisited. Lancet 2009; 373: 155-166.

- AFFIRM Investigators: A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1825-1833.

- Packer DL, et al: Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy: a reversible form of left ventricular dysfunction. Am J Cardiol 1986; 57: 563-570.

- Kay GN, et al: The Ablate and Pace Trial: a prospective study of catheter ablation of the AV conduction system and permanent pacemaker implantation for treatment of atrial fibrillation. APT Investigators. Interv Card Electrophysiol 1998 Jun; 2(2): 121-135.

- Cosio FG, et al: Delayed rhythm control of atrial fibrillation may be a cause of failure to prevent recurrences: reasons for change to active antiarrhythmic treatment at the time of the first detected episode. Europace 2008; 10: 21-27.

- Kirchhof P: Can we improve outcomes in atrial fibrillation patients by early therapy? BMC Med 2009; 7: 72.

- Cosedis Nielsen J, et al: Radiofrequency Ablation as Initial Therapy in Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(17): 1587-1595.

- Wazni OM, et al: Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs as firstline treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation: A randomized trial. JAMA 2005; 293: 2634-2640.

- Steinberg BA, Pinccini JP: Anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. BMJ 2014; 348: g2116.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- All patients over 65 years of age should be screened for atrial fibrillation by pulse palpation. If the pulse is irregular, the diagnosis should be verified by ECG.

- Any patient over the age of 65 with atrial fibrillation has an indication for oral anticoagulation (OAC).

- Patients with a CHA2DS2VAScscore of 0 points do not require OAK and antiplatelet agents for embolic prophylaxis. Female sex with age less than 65 years and lack of other risk factors does not warrant OAK.

- In asymptomatic AF, aim for a rate <110/min at rest and monitor by Holter ECG. If performance deteriorates with atrial fibrillation, tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy should be considered. In symptomatic patients, the resting rate should be <80/min.

- In symptomatic atrial fibrillation, rhythm control should be sought. In paroxysmal AF without structural heart disease, current guidelines allow radiofrequency ablation of AF to be performed as first-line therapy.

GP PRACTICE 2014; 9 (9): 11-17